Installation view, Monuments, The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA. Courtesy of The Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) and The Brick. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen.

The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA, Los Angeles, and The Brick, Los Angeles

23 October 2025 – 3 May 2026

by JILL SPALDING

Reassessment has precedent. Both the Louvre and the Getty museums bear witness to millennia of political and religious desecration; Mesopotamia’s disfigured bronze statues (Sargon of Akkad), Egypt’s hacked pharaohs (Hatshepsut), ancient Greece’s maimed deities (The Sphinx), Hindu temples’ smashed idols (Narasimha at Hampi), and countless mutilations of the Buddha, now seared into memory by the destruction at Bamiyan, Afghanistan.

Centuries later, be it for dominance, revenge or redress, the push to erasure truncated, toppled, defaced or demolished offending statues of Napoleon, Tsar Alexander II, Colombia’s founders, Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada and Simon Bolivar, the Soviet Union’s tyrannous Joseph Stalin, China’s repressive Chiang Kai-shek and – rebelling even against the compassionate – the crucified Jesus and patriotic Joan of Arc.

More recently, for their histories of oppression, genocide, slavery and land theft, the aggrieved assaulted Latin America’s detested icons. In 2019, the Mapuche Indigenous people demolished the statue of Chile’s ruthless Spanish conquistador Pedro de Valdivia, and in 2020, at a sacred ancient cemetery in Popayán, Colombia, the Misak people toppled the equestrian statue of Spain’s famed conquistador Sebastián de Belalcázar. Lending Monuments immediate relevance, just weeks ago, protesters destroyed statues of Nicolás Maduro.

-IMG_7289.jpg)

Laura Gardin Fraser, statue of generals Stonewall Jackson and Robert E Lee. Installation view, Monuments, The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA. Courtesy of The Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) and The Brick. Photo: Jill Spalding.

Closer to home, fuelled by racism and social injustice, in the last decade activists have removed statues of Christopher Columbus in at least six major cities, defaced Jefferson Davis, toppled Robert E Lee, and vandalised even bronze replicas of Thomas Jefferson and George Washington.

Their fall from grace is well documented – in 2017, Monument Lab: Philadelphia vigorously contested their histories through art. But that the exhibition at MOCA, planned under President Biden, has opened under Trump, whose executive orders are having countless Confederate monuments reinstated, gives revisionist history a renewed urgency and searing poignancy.

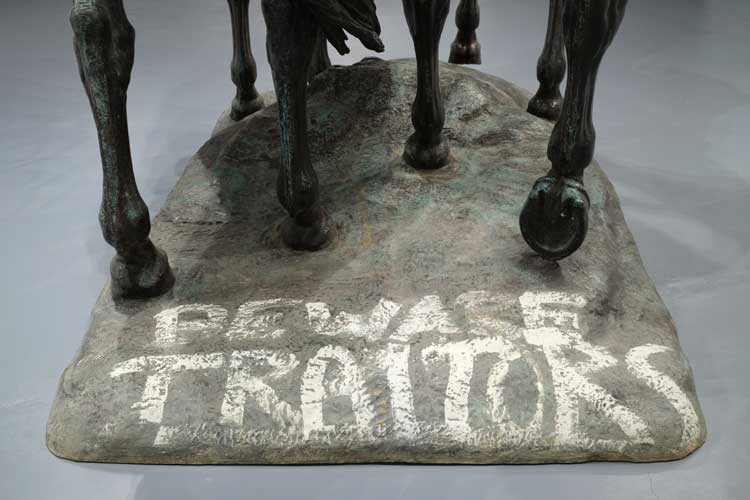

The monuments shown here – 10 decommissioned Confederate statues too massive to travel – could have stood on their own had the curators’ intention been to relay but their awe and terror. Paint-spraying the face of Supreme Court Justice Roger B Taney doesn’t mask the fearsome entitlement of his infamous 1857 Dred Scott v Sandford decision, that Black people had “no rights which the white man was bound to respect”, nor does “BEWARE TRAITORS” spray-painted on its base blight the menace of Laura Gardin Fraser’s controversial equestrian statue of the South’s generals Stonewall Jackson and Robert E Lee.

BEWARE TRAITORS spray-painted on the base of Laura Gardin Fraser's statue of generals Stonewall Jackson and Robert E Lee. Installation view, Monuments, The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA. Courtesy of The Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) and The Brick. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen.

However, although perhaps inadvertent, the curatorial decision to place each of these monuments in dialogue with a contemporary work of art risks complicating their impact. Undertaken to widen the conversation about offending public commissions, the result is to confuse their message by proposing the monument itself as an artwork.

Again, there is precedent. Impossible not to marvel at the equestrian statues of Alexander the Great by Lysippos; of Erasmo da Narni by Donatello, of Peter the Great by Falconet, of William Tecumseh Sherman by Saint-Gaudens. And few would argue with housing Michelangelo’s David in a museum.

Kara Walker, Unmanned Drone, 2023. Photo: Installation view, Monuments, The Brick. Courtesy of The Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) and The Brick. Photo: Ruben Diaz.

But doesn’t a reviled monument exhibited in a museum lose its sting? So might you react to Unmanned Drone (2023), Kara Walker’s complex and much touted sole entry at The Brick, undertaken to render palpable white oppression. With a mastery that trips over itself, so deftly have the heads and limbs been hacked from a decommissioned bronze statue of Stonewall Jackson and his steed and so weirdly have they been reconfigured into a hideous 11ft-tall Centaur as to mitigate its impact from horrifying to unsettling.

Hank Willis Thomas, Suspension of Hostilities, 2019. 1969 Dodge Charger. Installation view, Monuments, The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA. Courtesy of The Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) and The Brick. Photo: Jill Spalding.

Specific to this exhibition, another caveat is the failure of several of the contemporary artworks to mark at all. A monument need not be massive, but it must convey power. You would have to know a lot about the history of film and the Confederacy to read A Suspension of Hostilities (2019), Hank Willis Thomas’s toppled replica of the shiny Dodge Charger in the Dukes of Hazzard TV series, as a loathed Southern symbol of white supremacy normalised in Black entertainment.

Matthew Fontaine Maury statue next to Walter Price’s series Cadence, 2022-24. Installation view, Monuments, The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA. Courtesy of The Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) and The Brick. Photo: Jill Spalding.

A stretch, too, to play canvas against monuments. Although Walter Price’s large-scale series Cadence (2022-24) is embedded with his footprints to reframe the history of slavery and forced labour manifested by the adjacent Matthew Fontaine Maury statue, they still read more as abstract paintings.

Andres Serrano, The Klan, 1990. Installation view, Monuments, The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA. Courtesy of The Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) and The Brick. Photo: Jill Spalding.

The same problem applies to photography. Placed by these brutalist bronzes, both The Klan (1990), Andres Serrano’s colour portraits depicting Klansmen hiding behind hoods, and Birth of a Nation (2025), Stan Douglas’s five-channel silent reshoot of DW Griffith’s 1915 film, convey the Ku Klux Klan’s message, not dominion.

Nona Faustine, Ye Are My Witness, Brooklyn, New York, 2018.

Best focus on the works that deliver. Surprisingly moving for images that were staged, Ye Are My Witness, Brooklyn, New York (2018), photographs from the late Nona Faustine’s White Shoes series, which she composed at sites historically linked to enslavement, present her body as a powerful “counter-monument” to prejudice.

Although formed from a monument, conceptually the most interesting challenge is the transformation of the vainglorious bronze portrait of General Robert E Lee in Charlottesville, Virginia, into ingots stamped Swords into Plowshares (2023), that a community effort had melted down from the statue. As stacked here next to granite fragments from its base after the statue’s removal triggered gatherings of armed white supremacists, these relics would have sufficed to impart the US’s economic foundation in slavery but, as a nearby text discloses, they will be refashioned into an inclusive artwork.

Khalil Robert Irving, New Nation (States) Battle of Manassas, 2014. Installation view, Monuments, The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA. Courtesy of The Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) and The Brick. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen.

Other standouts are Khalil Robert Irving’s intricate cast-bronze tabletop New Nation (States) Battle of Manassas (2014), modelled on thousands of images of such as torched cars and broken bottles from the unrest at Ferguson, St Louis, following the police killing of Michael Brown, and Cauleen Smith’s eleborate installation, The Warden (2025), that faces Edward Virginius Valentine’s 1907 Vindicatrix (an allegorical figure once atop Richmond, Virginia’s offending Jefferson Davis monument) on to black mirrors wired to flash it with streaks of red, white, and blue. Oddly moving, Confederate Soldiers and Sailors (1903), Frederic Wellington Ruckstull’s emotive portrayal of a righteous angel carrying a fallen soldier to heaven that was defiled because commissioned by the Maryland daughters of the Confederacy to honour one of their own.

There is no ambiguity about Abigail DeVille’s Deo Vindice (Orion’s Cabinet) (2025),an elaborate installation referencing the Confederacy’s motto that commandsMOCA’s entire second floor. Its immersive eerily flamed sequence of charred interiors and furnishings painstakingly recreated from civil war photographs to evoke the burning of Richmond, gives lie to Trump’s “America for America” with an immediacy that renders the vengeance so searingly palpable as to tear at the heart and boggle the brain.

Abigail DeVille, Deo Vindice (Orion’s Cabinet), 2025. Installation view, Monuments, The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA. Courtesy of The Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) and The Brick. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen.

Bring both history and aesthetics to this marking exhibition and you, too, may come away with two different views of it; contested monuments both as offending symbols and, placed in dialogue with artworks, as sculpture, to be viewed and preserved.

Fortuitous that Bahamian artist Tavares Strachan’s tour de force exhibit, The Day Tomorrow Began, is running concurrently, until 29 March 2026, at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Not only is one of its six (six!) themed galleries titled Monument Hall, but the show in its entirety is a monument. Approach it less as art than as the life of a mind, rendered visible by a polymath who deploys his encyclopaedic knowledge and wide command of disparate materials to visibly reclaim Black histories that have too long languished in obscurity. Covering all four walls of the first gallery, The Encyclopedia Room, a dizzying 2,000-page collage of black-and-white prints and images titled Six Thousand Years (2018), challenges the scholarship of the Encyclopaedia Brittanica with more than 17,000 single entries extracted from The Encyclopedia of Invisibility (walnut #3), Strachan’s all-encompassing recordof lost or ignored facts, figures and places that traces the Black experience through time.

Wondrous how ingeniously they take shape in four other galleries. Never heard of America’s first Black explorer, Matthew Henson; first Black astronaut Robert Henry Lawrence Jr; first US Army’s female deep-sea diver and the first Black female deep-sea diver across all US military branches, Andrea Crabtree? Meet them here, rendered in painted pulp, ceramic, marble, glass and bronze.

How does Haiti’s King Henri Christophe relate to Napoleon? Find out in Monument Hall, where loaded pairings in media as diverse as resin, metal, electrodes, argon gas, hair and reindeer hides depict such as Pablo Picasso with an Ife king, anti-apartheid activist Steve Biko with Winston Churchill, Harriet Tubman with an alligator and, via a large, inverted neon word piece, Mark Twain in dialogue with James Baldwin.

In the Gemini gallery, versatile extends to the illusion of “paintings” formed of tiny, seemingly monochromatic tiles, until closer viewing reveals them to be intersecting multicoloured portraits and word-search puzzles.

Tavares Strachan, Rice Grass Meadow Gallery. Installation view, Monuments, The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA. Courtesy of The Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) and The Brick. Photo: Jill Spalding.

Wondrous, too, in the scented, gently waving Rice Grass Meadow Gallery how Strachan connects figures over centuries, though you’ll need the paper diagram offered there to locate the head of the musician and civil rights activist Nina Simone, emerging from that of Babylon’s Queen of Sheba.

Tavares Strachan, Barbershop, installation view, Monuments, The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA. Courtesy of The Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) and The Brick. Photo: Jill Spalding.

Don’t think you have lost out should you miss the sporadic performances enacting the doings in a Black barbershop and laundromat, the painstaking reproductions in charcoal-grey and ice-white of the machinery, implements and products that flag the bleached-out lives of their customers immerse you as completely in their world as if detailed in a painting by Kerry James Marshall.

Tavares Strachan, Laundromat, installation view, Monuments, The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA. Courtesy of The Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) and The Brick. Photo: Jill Spalding.

Although still mid-career at the age of 46, of all the recovered, uncovered, discovered, artists who have thankfully surfaced in this revisionist decade, Strachan is the closest Black equivalent of the Renaissance Man. Gobsmacked is not too big a word for genius made visible with such high artistry as to leave you forgetting you came to see an art show.