Marian Goodman, London

5 December 2020 – 19 January 2021

by BETH WILLIAMSON

I was fortunate to be able to see the new exhibition of work by the American artist Robert Smithson (1938-73) at Marian Goodman Galley in London before the gallery had to close due to a second lockdown in England. Smithson is best known for his earthworks, and his most famous, Spiral Jetty and Partially Buried Woodshed (both 1970), are now 50 years old. This exhibition focuses on his enduring interest in islands and is special for a number of reasons. First, it is largely drawn from the private collection of Smithson’s wife, Nancy Holt (1938-2014). Second, it has been cleverly conceived of by Marian Goodman as one of two companion exhibitions of Smithson’s work, the other being Robert Smithson: Primordial Beings at Marian Goodman’s Paris gallery. Third, this is the last exhibition to be shown at Marian Goodman’s Lower John Street space in London before it reconfigures its curatorial strategy, offering a more flexible approach across the city with Marian Goodman Projects in 2021.

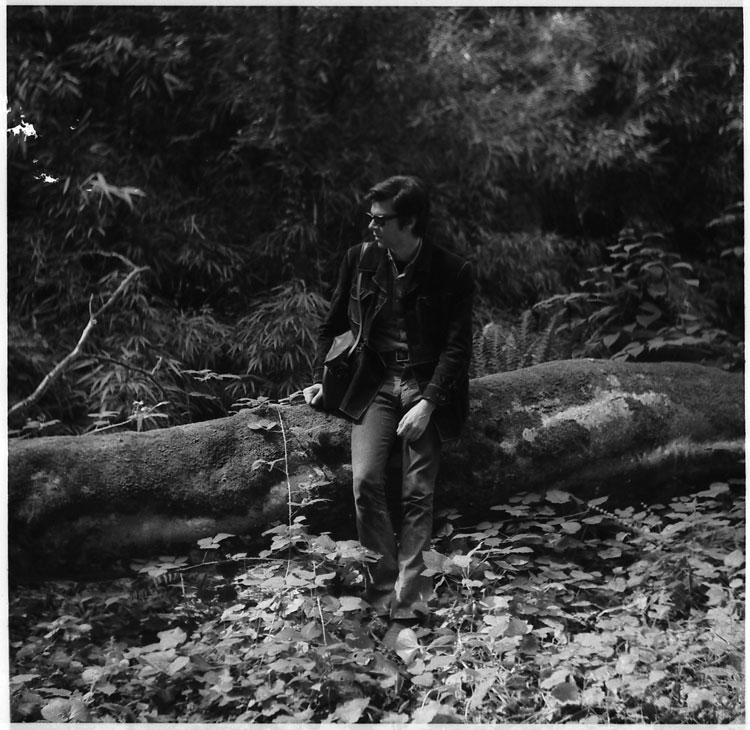

Robert Smithson in the UK working on a Mirror Displacement in 1969,

photographed by Nancy Holt. © Holt/Smithson Foundation, licensed by VAGA at ARS, New York.

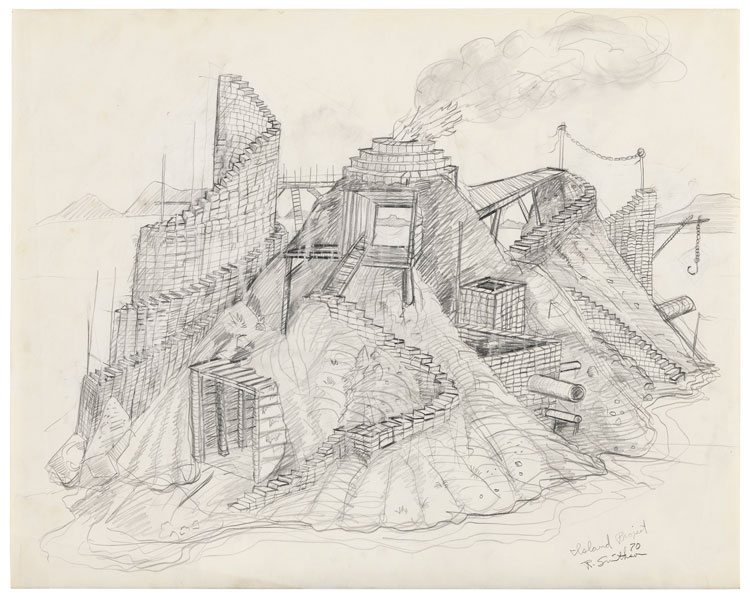

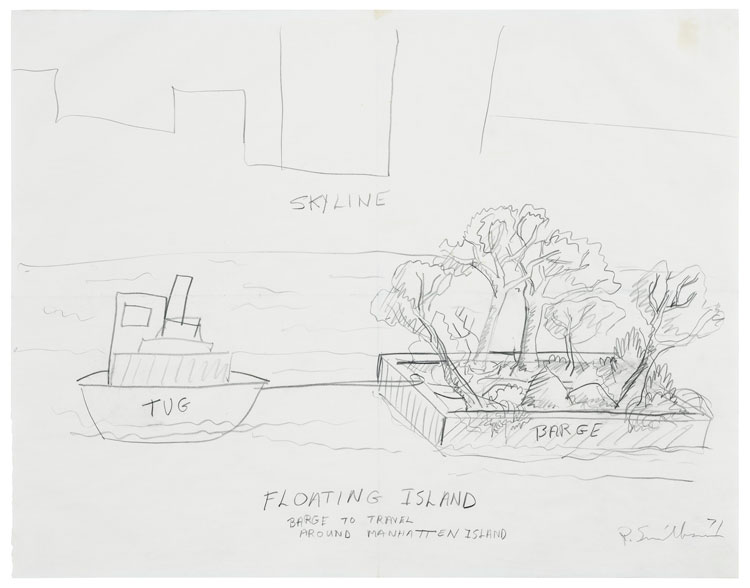

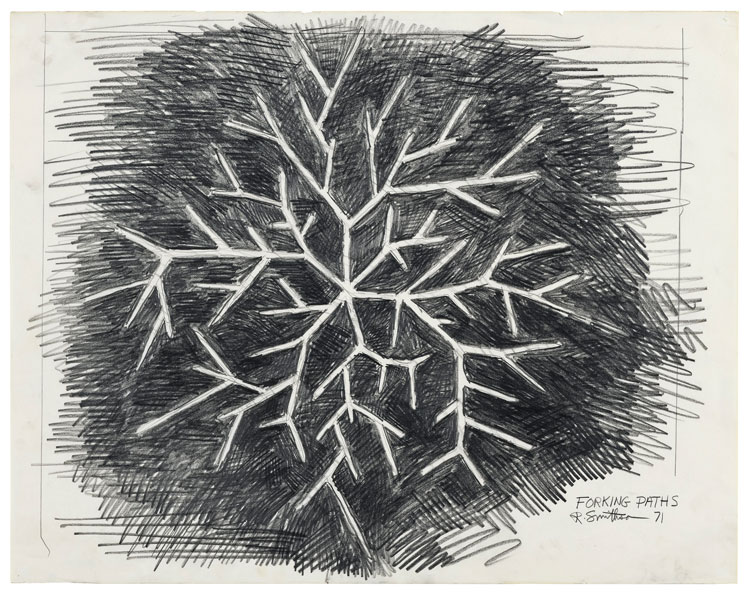

Smithson once said: “There should be artist-consultants in every major industry in America.” His strength of conviction here is easy to imagine as we see, in this exhibition, his passion for building. Island projects with flags, turrets and furnaces give way to jetties, paths and juggernauts. These constructions are imagined, designed, drawn and built with a variety of materials. Smithson explores the idea of the island in its form and material and conceives a circular island, an island mound with a flat top, a forking island, an island of ashes, an island maze and an island fort. An island of mangrove plants is especially appealing, an idea Smithson engages within the ink drawing Mangrove Seedlings planted in shallow lagoon Summerland Key Florida (1971) and developed in Nancy Holt’s film Mangrove Ring: Summerland Key, Florida of the same year. Smithson’s islands, spirals, mazes, floating structures and buried structures feature cement oceans, concrete strata, rocks and broken slates. This exhibition may not include any of Smithson’s nonsites, but his earthworks are there in their filmic form with 35 minutes of Smithson’s Spiral Jetty (1970) and Nancy Holt’s The Making of Amarillo Ramp (1973-2013), for instance. The majority of works are drawings in pencil or ink on paper, alongside a handful of other forms – mirror, photostat, gouache, metal, light and neon.

Robert Smithson. Island Project, 1970. Pencil on paper, 19 x 24 in (48.3 x 61 cm). © Holt/Smithson Foundation, Licensed by VAGA at ARS, New York. Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery New York, Paris and London.

The Eliminator (1964/2004) is transfixing. It is a visual island made of red neon light that turns on and off repeatedly, so disrupting perception and disorienting the viewer. The gallery information recounts Smithson’s description of The Eliminator as a sculpture that “overloads the eye whenever the red neon flashes on, and in so doing diminishes the viewer’s memory dependencies or traces”. He continues: “Light, mirror reflection and shadow fabricate the perceptual intake of the eyes. Unreality becomes actual and solid. The Eliminator is a clock that doesn’t keep time, but loses it.” This makes complete sense of the experience of The Eliminator – it is disconcerting and our usual grip on time and space is shaken loose.

Holt’s The Making of Amarillo Ramp is a poignant film. Seventeen miles north west of Amarillo, Texas, Smithson, then aged 35, staked-out the ramp he planned to build. On 20 July 1973, during a flight to view it, the plane transporting Smithson and a photographer crashed. The two men and the pilot were killed. From 3 August to 1 September 1973 Nancy Holt, Richard Serra and Tony Shafrazi completed Smithson’s project. The vastness of the landscape is evident as people and even trucks appear minuscule. Despite this incongruity, earth is moved, construction takes place and the ramp begins to form and extend as the trio work together to achieve Smithson’s singular vision. When a truck topples over, humankind and machine work together to right it again and the adversity is overcome. Despite the magnitude of construction, sections are paced out and measured in human scale so that the gentle curvature and slope of the ramp sit comfortably in the landscape.

Robert Smithson. Floating Island – Barge to Travel around Manhattan Island, 1971. Graphite on paper, 18 1/4 x 23 1/4 in (46.2 x 58.9 cm). © Holt/Smithson Foundation, Licensed by VAGA at ARS, New York. Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery New York, Paris and London.

In Mono Lake (1968), made by Holt and Smithson, there is the feel of close friends on a road trip, but with a serious purpose. Smithson’s interest in geology is at the centre of their activities as they drive out to the Californian lake. Smithson’s voiceover supplies us with myriad facts about the lake. It is 15 miles wide (24km) and 20 miles (32km) long, a refuge for marine life, home to secretions that coalesce to form coral-like structures and masses of flies that cover the shoreline and the beach. Smithson explains the difficulty of climbing the steep slope at the north end of the lake as the ground shifts underfoot, flowing downwards like a river of stones, a kind of fluvial entropy in action. The scene shifts to Lake Tahoe where Smithson, who is toasting marshmallows, looks at a map. He begins to burn the map spread out on the ground before him, encroaching on the landscape both real and imagined. The cinders were collected by Smithson and used to make the sculpture Mono Lake Nonsite (1968).

Robert Smithson. Forking Paths, 1971. Pencil on paper, 19 x 24 in (48.3 x 61 cm). © Holt/Smithson Foundation, Licensed by VAGA at ARS, New York. Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery New York, Paris and London.

All of this tells us that Smithson was a builder not a destroyer. Still, his enduring interest in entropy is ubiquitous in his work and in this exhibition. In his essay A Sedimentation of the Mind: Earth Projects, first published in Artforum in 1968, Smithson engaged more fully than before with the ideas of the art theorist Anton Ehrenzweig (1908-66), taking up his notion of dedifferentiation, using it as a synonym for entropy, and making comparisons between mind and matter. “The Earth’s surface and the figments of the mind have a way of disintegrating into discrete regions of art … One’s mind and the earth are in a constant state of erosion, mental rivers wear away abstract banks, brain waves undermine cliffs of thought, ideas decompose into stones of unknowing, and conceptual crystallizations break apart into deposits of gritty reason.”

Viewing the works in this exhibition helps us to understand what Smithson was about. The focus on his hypothetical islands through drawing, sculpture and film helps to bring clarity to his ideas about entropy, knowledge and the Earth’s surface. The sheer number of variations in his drawings, too, perhaps lends a stronger sense of his conviction to his island projects and a practice that not only changed what art could be, but continues to have significance today.

Photographer Merlin Daleman talks about how his new photo book, Mutiny, captures the backstory of th...

Three seductive, spellbinding films demonstrate the Uzbek artist and film-maker Saodat Ismailova’s...

German painter Gerhard Richter enchants, astonishes and unnerves in this compendious retrospective, ...

Karimah Ashadu’s three films may aim to give a voice to marginalised men in the former British col...

Playing with Fire: Edmund de Waal and Axel Salto

The artist and author Edmund de Waal has curated the first major exhibition of the Danish ceramicist...

Women of Influence: The Pattle Sisters

Seven sisters made their mark on Victorian art and culture and deserve to be far more than just dist...

Anindita Dutta: The Shadows of Duality

Shifting from her usual clay to recycled shoes, animal hides, fur, fabrics and more, Anindita Dutta ...

Berthe Weill: Art Dealer of the Parisian Avant-garde

This milestone exhibition celebrates the pioneering art dealer Berthe Weill, who launched the career...

Artes Visuales: The Latin American Avant-Garde in Print

Focusing on the influential Artes Visuales magazine and the extraordinary experimental artists it fe...

Rae-Yen Song 宋瑞渊, •~TUA~• 大眼 •~MAK~•

This is a theatrical space like no other in which, using sculpture, sound, textiles and performance,...

Celebrating the photographic work of Lee Miller in grand style, this retrospective showcases her man...

Now in her 70s, and with a show at the Irish Museum of Modern Art in Dublin, Cecilia Vicuña’s act...

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith: Wilding

This posthumous exhibition of Jaune Quick-to-See Smith’s art includes work made right up to her de...

Ayoung Kim: Delivery Dancer Codex

A trilogy of video works featuring two queer, female delivery drivers in Seoul, Ayoung Kim’s Deliv...

The Tate’s landmark exhibition presents a fascinating story, but could have done more to capture t...

Known as a gallerist to the likes of Rauschenberg and Rothko, Betty Parsons spent her weekends makin...

In a powerful new show of painting, sculpture and film, the artist brings folkloric traditions and m...

Robert MacBryde and Robert Colquhoun: Artists, Lovers, Outsiders

The two men from working-class Scottish backgrounds met at art school and became inseparable. This e...

Push the Limits: Culture Strips to Reveal War

A diverse group of works in this exhibition at Fondazione Merz show how contemporary art responds to...

Artes Mundi 11 Prize and Exhibition

Against a background of divisive global politics and hysteria around migration, the six artists shor...

At Aberystwyth Arts Centre, Anawana Haloba has staged an “experimental opera”, as she terms this...

Jumana Emil Abboud – interview

Drawing on folklore, mythmaking and storytelling, Jumana Emil Abboud articulates the strains placed ...

Rhiannon Hiles, chief executive, Beamish Museum – interview

Winner of the world’s largest museum prize, the £120,000 Art Fund Museum of the Year, Beamish, an...

Whether depicting women at work, children playing on the beach or locals at prayer Anna Ancher’s l...

Wright of Derby: From the Shadows

The National Gallery reunifies Joseph Wright of Derby’s trio of candlelit masterpieces, while reve...

Wayne Thiebaud: American Still Life

A luscious selection of sweets, cakes and pies seduce us at this, American painter Wayne Thiebaud’...

A Story of South Asian Art: Mrinalini Mukherjee and Her Circle

This visually thrilling exhibition is a revelation. Pivoting around Mrinalini Mukherjee, it also cel...

Following in the female surrealist tradition, Holly Stevenson makes cathectic objects from clay, whi...

Vision and Illusion: Architectural Photographs by Hélène Binet

A research project by the University of Oxford into Jewish country houses, tracing their history and...

American artist Lucy Raven’s eloquent new film tracks a remarkable undoing, as the dammed Klamath ...