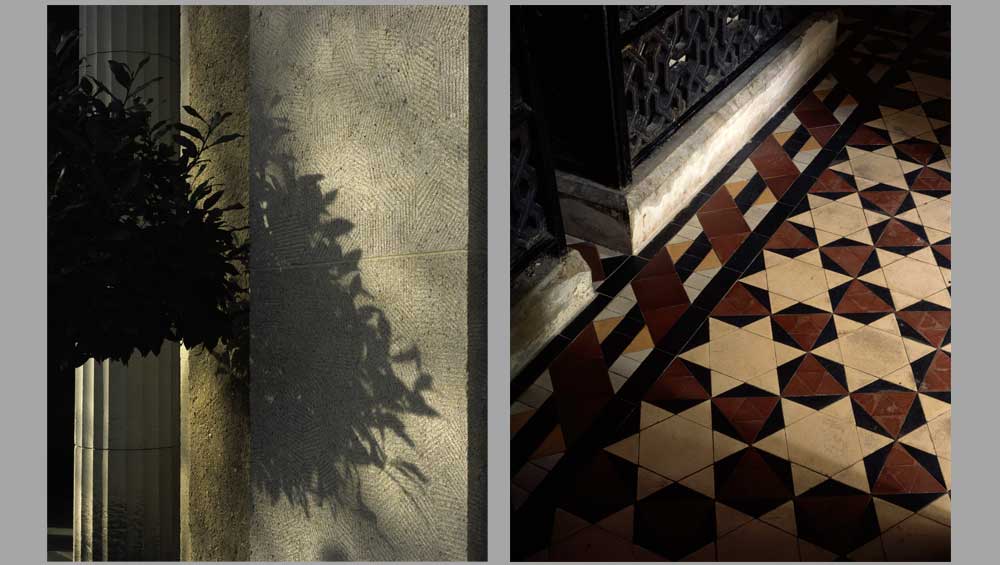

Left: Liebermann-Villa. Digital c-print. Photo Hélène Binet. Right: Montefiore Mausoleum, 3-2020, Digital c-print. Photo: Hélène Binet.

Liebermann Villa at Wannsee, Berlin

20 September 2025 – 19 January 2026

by SABINE SCHERECK

The splendour of English country houses attracts many visitors, but their facades never reveal their owners. The University of Oxford decided to take a closer look in 2015, when it launched its research project Jewish Country Houses, to trace houses owned, built or renovated by Jews– not only in England but throughout Europe – to reveal a significant aspect of European Jewish heritage and material culture.

Country houses in general reflected the desire for a private refuge from the city. In Britain, the right of Jews to own freehold land was contested until the early 1830s. After this time, more Jewish-owned houses emerged. For Jewish families, these houses were symbols of the social status they had achieved, their integration into society and their cultural affiliation. They were clear markers of the newly emancipated Jewish communities.

The Jewish Country Houses Project identified houses across England, France, Germany, Italy and the Czech Republic and commissioned the photographer Hélène Binet to portray a selected few. One of these was the Liebermann Villa at Wannsee, and it is now hosting the exhibition Vision and Illusion, which presents her results. It comprises 24 images in black and white and colour. Rather than providing mere documentation, key to Binet’s work was accentuating the special character of the houses, particularly as they often also gave clues to the personality of the owner. Interestingly, the research showed that there was no specific Jewish feature common to all houses.

Waddesdon Manor, 10-2022. Hand printed b/w silver gelatin. Photo: Hélène Binet.

After a brief introduction, the exhibition begins with impressions of Waddesdon Manor in Buckinghamshire, a grand estate, where Binet’s work was shown in the summer. At Waddesdon, the curator, Juliet Carey, grouped the images following different motifs found at the houses, such as floral ornaments, while at the Liebermann Villa the curator, Viktoria Krieger, has arranged them by location, creating an architectural journey through Europe. Accompanying wall texts offer a cultural context to these houses as well as deepening the insight into European Jewish history. This is a much valued addition: at Waddesdon Manor, the presentation concept did not include wall texts and for further information about the houses, the visitor had to draw on the book Jewish Country Houses. It is a fine and comprehensive book, in which more country houses than in the exhibition are covered.

Waddesdon Manor, 10-2022. Digital c-print. Photo: Hélène Binet.

Waddesdon Manor was built by Baron Ferdinand de Rothschild between 1874 and 1885. Modelled on the style of a French Renaissance chateau, as found along the Loire valley, this stately manor reflected his love for France. His fondness for France was probably rooted in his place of birth, Paris, since his parents were of English and Austrian origin and he spent time in Vienna and Frankfurt before settling in England in 1860. He was a banker and politician and his impressive property, surrounded by nearly 11sq km land (2,700 acres), was to entertain his prominent and cosmopolitan guests as well as to showcase his art and antique collection, including 18th-century French furniture. In 1957, the Rothschild family handed the estate the National Trust to preserve it and make it accessible to the public, although it is still managed by the Rothschild Foundation.

Binet captured the house with views of the small towers, roofs and columns. Though Binet’s photographs offer unusual perspectives of the house, to experience the true magnificence of the house with its 240 rooms (45 of which are open to the public), a look at its website, or better, a visit to the house itself is recommended.

Strawberry Hill, 04-2021. Hand printed b/w silver gelatin. Photo: Hélène Binet.

Much more modest in size, furnishing and decor is the Georgian Gothic revival-style Strawberry Hill House and Gardens in Twickenham, south-west London, conceived by Horace Walpole in 1747. The Jewish part of its history begins in about 1850, when Frances Waldegrave, daughter of a renowned Jewish opera singer, inherited the house. She made significant amendments and added features with Jewish content. The photographs picture rich delicate stucco and a ceiling with golden stars on a white background.

Strawberry Hill, 04-11. Digital c-print. Photo: Hélène Binet.

Also in England are the Montefiore Synagogue and Mausoleum created by the banker and philanthropist Sir Moses Montefiore. After having acquired East Cliff Lodge in Ramsgate in Kent in 1831, he added a private synagogue and a mausoleum to the estate. The synagogue enabled him to worship in the Sephardic tradition, a feature, which can be seen in the context of the time, when many Christians also included private chapels in their residences. Not much is left of East Cliff Lodge and the synagogue, but the mausoleum stands out through Binet’s focus on its floor with its oriental pattern featuring stars.

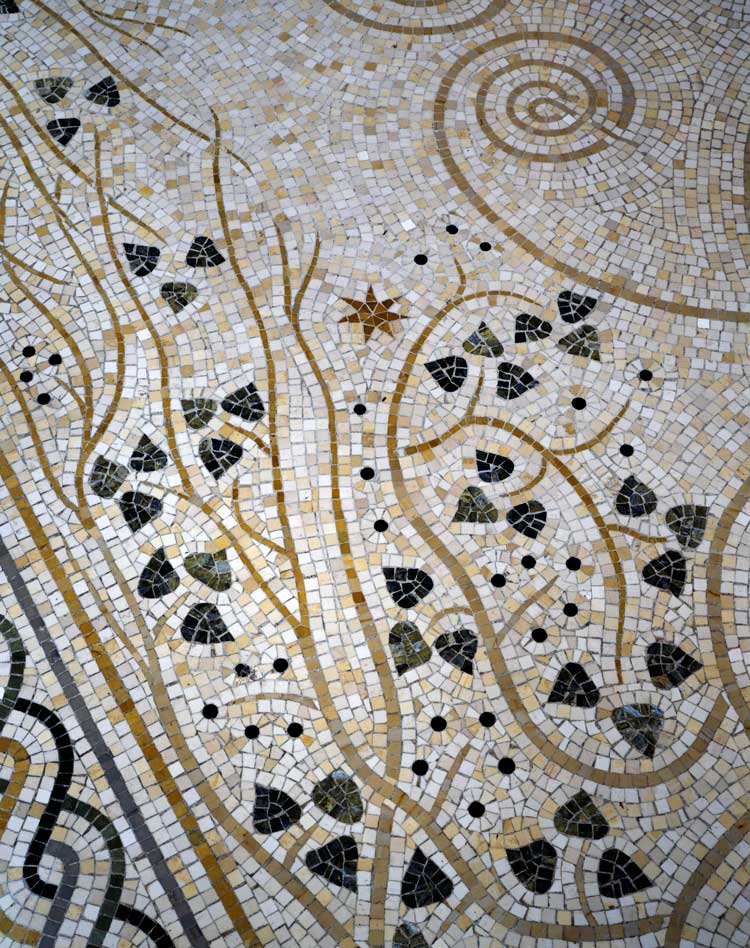

Villa Kérylos, 11-2022. Digital c-print. Photo: Hélène Binet.

At the Villa Kérylos, the bright light and warmth of the south are evoked by a mosaic reminiscent of Greek art. It shows green ivy twining around golden branches on a white ground. It is a detail of the villa, which is not located in Greece as could be easily assumed, but in Beaulieu-sur-Mer on the French Riviera. In the same way that De Rothschild expressed his love for France with his château-like manor, Théodore Reinach manifested his deep connection to ancient Greece with his villa. This connection is also reflected in his professions: he was a historian and archaeologist. The house was built between 1902 and 1908 and can be seen from the Villa Ephrussi de Rothschild on Cap Ferrat, which is not included here, but is a great attraction of the region. The latter was created in 1907-12, about the same time as the Villa Kérylos, by Béatrice de Rothschild in an Italian Renaissance style. The De Rothschilds and the Reinachs were related through marriage. A connection to the Liebermann Villa also comes into play here: the art collectors Felicie and Carl Bernstein, to whom the villa dedicated an exhibition earlier this year, also belonged to their large family circle, being related to the Ephrussis.

Villa Kérylos 11-2022. Digital c-print. Photo: Hélène Binet.

Villa Kérylos, 11-2022. Digital c-print. Photo: Hélène Binet.

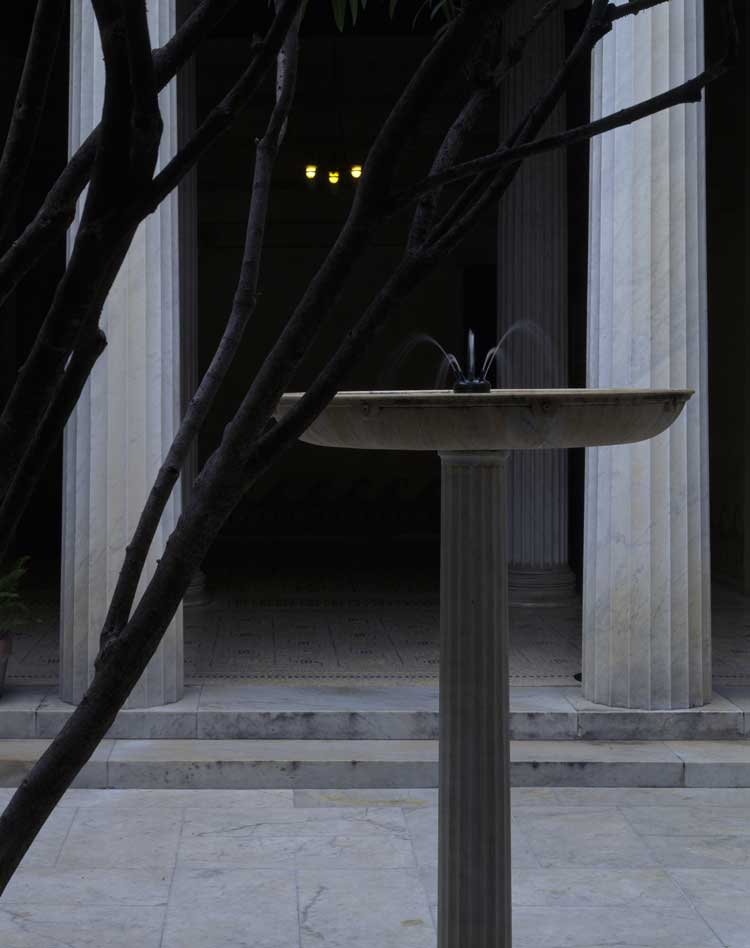

Max Liebermann began working on his villa in 1909 and moved in the following year. He opted for a classicist style and kept the design, in contrast to many other homes presented here, rather simple and easy to navigate. It has only one small reference to a far away place: the Italian inspired loggia with its blue walls and plant motifs. It is a nod to his travels to Italy, to which the museum took a closer look in last year’s exhibition To Italy! With Liebermann in Venice, Florence and Rome.

Liebermann Villa, 11-2021. Digital c-print. Photo: Hélène Binet.

The plant motif runs like a common thread through the Binet’s observations at the Liebermann Villa. Catching the eye is the shadow play produced by the leaves of an ornamental tree in the evening sun, creating a Mediterranean feel. In contrast to previous exhibitions at the house, the window shutters of the rooms are now open, offering a view into the large garden in the way Liebermann had conceived it. This gives visitors a sense of what it was like to live in a country house, where closeness to nature was a key factor.

Villa Tugendhat 11-2022. Hand printed b/w silver gelatin. Photo: Hélène Binet.

Although hardly any of these houses reflect the religion of their owners, many adopted a historicising style. The Villa Tugendhat in Brno in the Czech Republic is a great exception. Built in 1929-30 by the German architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe for Greta und Fritz Tugendhat, it showcases the architectural avant garde of the time. Its sleek design and no-frills approach, which drew on the ideas of the Bauhaus, is now considered a masterpiece of modernity. This was no lavish country estate where its owners spent their summers – it was a house on a rise in the city, in which the Tugendhats lived. Here, too, Binet works in black and white and enchants with the intricate pattern produced by the shadows of grasses, leaves and plants. The picture is enhanced by the reflection of the surrounding nature on the glass walls adding another layer to the image – all in all producing a dazzling effect. At the same time, it is very telling as glass was a prominent feature of modern architecture.

Binet’s works show a love for detail and emanate a great calmness. The visitor can feel how she took the time to get to know the houses. Her compositions are often marked by the tension between twirling shapes and straight lines, horizontal and vertical. Besides offering glimpses of these diverse estates, the true achievement of the show is to highlight the contribution Jews made to the cultural heritage of the respective countries.