Beamish, The Living Museum of the North, winner of the Art Fund Museum of the Year 2025. Photo: David Oates

by NICOLA HOMER

Beamish, the Living Museum of the North, is an open-air social history museum in County Durham. It won the Art Fund Museum of the Year 2025 award, which is a £120,000 prize. Situated in the village of Beamish, between Durham and Newcastle, the museum encourages visitors to imagine everyday life in the region in Georgian, Victorian and Edwardian times, and in the 1940s and 1950s, while preserving local heritage and focusing on the industrial era. It makes a significant contribution to the region’s economy and has more than 360 volunteers and employs in excess of 500 staff. In 2024, Beamish surpassed its pre-pandemic visitor numbers by attracting almost 839,000 people. An independent trust, Beamish was a beneficiary of the government’s Covid furlough scheme and the culture recovery fund to help organisations during the pandemic, during which it launched an online shop.

Left to right: Jenny Waldman, Director of Art Fund, Rhiannon Hiles, Chief Executive of Beamish, and Culture Secretary Lisa Nandy at the Art Fund Museum of the Year 2025 ceremony earlier this year. Photo: David Oates.

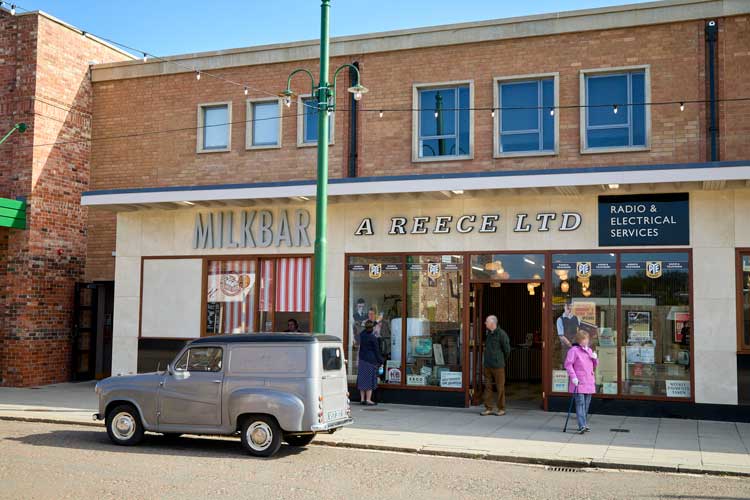

The museum has completed a major capital project, supported by the Heritage Lottery Fund. The Remaking Beamish project has created more than 30 immersive exhibits, including its 1950s town with a replica of the Grand electric cinema from Ryhope, Sunderland, originally built in 1912, featuring stained-glass windows. A centre point within the 1950s townscape that has been recreated are “aged miners’ cottages”, copied from houses in South Shields, which tell a story of welfare provision for retired miners in County Durham. On the day of the visit of the Art Fund judges, a volunteer was playing 1940s wartime music on the piano and a group started singing together there. Beamish’s chief executive, Rhiannon Hiles, said: “That’s kind of the atmosphere you have when you go into that space. It’s a genuine response to the music being played or to conversations taking place.”

Beamish received the award last June at the Museum of Liverpool. Hiles was presented with the £120,000 prize by the comedian Phil Wang, who was one of the judges. The award recognised inspiring projects and activity between autumn 2023 and winter 2024. The judging panel was chaired by Jenny Waldman, director of the Art Fund, and included, along with Wang, the artist Rana Begum, David Dibosa, director of research and interpretation at Tate, and Jane Richardson, chief executive of Museum Wales.

Beamish, The Living Museum of the North, winner of the Art Fund Museum of the Year 2025. Photo: © David Levene.

Waldman said: “Beamish is a museum brought to life by people – a joyous, immersive and unique place shaped by the stories and experiences of its community. The judges were blown away by the remarkable attention to detail of its exhibits across a 350-acre site and by the passion of its staff and volunteers.”

Studio International spoke by telephone to Rhiannon Hiles about Beamish’s visitor experience, how the museum offers educational programming to facilitate learning in science and engineering, and how it addresses the climate emergency. The following is an edited version of that interview.

Nicola Homer: Congratulations on winning the Art Fund Museum of the Year 2025 award. Inspired by Scandinavian folk museums, Beamish documents the local heritage of industrial communities in north-east England. The museum was described as having been “a jewel in the crown of the north-east for 55 years” by the chair of the judges. How does the museum tell a national story for an international audience?

Rhiannon Hiles: We are a regional museum rooted in the history of the people of the north-east. We tell industrial stories, rural stories, domestic stories, and a lot of what we represent at the museum tells a story that is tangible, which people can feel is relevant to them, wherever they are in the UK. One of the founding principles of our first director, Frank Atkinson, was to always have something that was within living memory. When we had moved into telling stories of the 1950s, the story of the NHS, the story of immigration and movement into regions across the UK, is one which we began to develop and to talk about more during our Remaking Beamish project – which is the biggest capital project the museum has ever done, supported by the Heritage Lottery and other trusts and foundations, across a 10-year period of work, interrupted by Covid, which extended it a little. That time we spent was invested in working with communities, working with people, about their history, so the stories are very much theirs. I think what we represent feels relevant to people from different working parts of the UK, and they are coming to understand and be immersed in stories that are familiar to them. We are the largest open-air museum in the UK. We have a wonderful open-air museum community. There are other brilliant ones – Blists Hill, St Fagans, Black Country Living Museum and others – but we are one of the biggest. Across Europe, we are looked at as being a leading open-air museum. We have memberships in our community across to Japan, China, the United States and Australia. We are seen as being an exemplar of what it can mean for an open-air museum to represent the stories of ordinary people and working lives, which is one of our massive strengths.

Beamish, The Living Museum of the North, winner of the Art Fund Museum of the Year 2025. Photo: © David Levene.

NH: The Remaking Beamish project includes Spain’s Field farm, which tells the story of farming in the 1950s in the north-east, and the expansion of a Georgian landscape. There is also a replica of “aged mineworkers’ homes”, a form of social housing, the facilities now providing a space for people living with dementia and other long-term health conditions. The 1950s town was built with input from local people with first-hand knowledge of the original space. How did you work together with the local community to create the exhibits?

RH: Beamish is defined by our communities. We spend a lot of our time and resources focused on ensuring that we are out in those communities. That time spent working with them means that in a way which is relevant for them, and which meets them at their level, we will then represent their stories back in the museum. It is their stories that have helped to define the area. I mentioned earlier the story of migration and immigration into and out of the region, and we worked with Italian families, particularly those who had set up ice-cream parlours and usually they were within people’s homes that they turned into these lovely Italian cafes. We were lucky to have one of the Italian families approach us. We worked with them and represented and recreated their dad’s shop and ice-cream parlour, using original booths. When you go into that space now, John’s image and his family images that they shared with us are on the walls. The way that the set-up is in the space when visitors come in there to buy their ice-creams, or just to walk through and listen to the 1950s music, is based on their memories.

Beamish, The Living Museum of the North, winner of the Art Fund Museum of the Year 2025. Photo: © David Levene.

In the open-air museum, we use original artefacts and items, collected during the collecting of the stories, so for us the stories are as important as the collections that help to tell those stories. One of our strengths at the museum is that all our exhibit spaces and areas are staffed and volunteered by our folks wearing costumes. They might be participating in something or encouraging others to take part in something, so it might be that someone sits down and plays Scrabble, and it helps to bring that space to life, but it also enables people to be interactive with the spaces they are coming in to visit. So, whether they can recall that era, or recall that story themselves or not, there is an opportunity to glean an understanding through immersive experiences, and that is something we are proud of.

The Remaking Beamish Project created more than 30 immersive experiences over this 10-year period, within the new 1950s town area, the takedown and rebuild of what was a derelict farmstead from Weardale in County Durham, and the development of Pockerley, which is set in the early 1800s, where we have an original stunning farmhouse, and you look down across the valley. The valley now has a Georgian wagonway, which takes steam engines from the early 1800s back and forth. There is a beautiful church, which was donated to us, and then rebuilt back in the museum just down in the valley. The lottery was delighted that we were going to bring original heritage buildings back into use, and we have created an area which has an immersive tavern – you feel you have stepped into the early 1800s – using collections. What sets us apart from a theme park is that within the spaces, there are original contexts, there is original material, original furnishings. One of the priorities of our open-air museum is to get as much of our collections out into spaces where people can experience them, and we have a pottery and immersive overnight accommodation. The lottery has been a fantastic partner of ours across this whole period and we match-funded the total cost of the project through trusts and foundations. As an independent museum, we also used our own surpluses wherever possible to feed straight back into the project lifespan.

Beamish, The Living Museum of the North, winner of the Art Fund Museum of the Year 2025. Photo: © David Levene.

NH: Beamish welcomes local visitors throughout the year and participates in national and international museum networks. Could you describe how the visitor experience changes through the seasons? Would you tell me about the traditional Christmas festivities from Georgian times to the 1950s?

RH: Absolutely. When we first thought about doing more through the wintertime, it was to ensure that the museum had a year-round offer. This is going back about 12 to 15 years, when we had been thinking about how we would get that year-round offer because we were aware that people still wanted to visit but the stories needed to change, and so as curators, the story of Christmas is an exciting one. I’m the vice-president of the Association of European Open-Air Museums and we go and see our colleagues’ museums, and of course their stories about Christmas are different from the regional one. We wanted to make sure that we would tell that story of Christmas through the eras that we have. The Georgian Christmas is different from the Christmas people would have experienced later, and so we show that between the time periods, between the Edwardian town, but also through the way in which people would represent themselves, according to where they might live or what their backgrounds were. Our Christmas in our Edwardian terrace is different in terms of representation from what you would see down in the pit village or up at the farm. The wartime Christmas has differences because of various impacts because of war. The Georgians would focus on activities and food to tell a story across the Christmas period, working up to Twelfth Night. Our Twelfth Night celebrations at Pockerley are beautiful, with music, with food. There is a beautiful cake which is made, the Twelfth Night cake, which was a Georgian approach to how you would then decorate it, using, if you could afford it, gilded on the top, but a lot of people would use colouring from pansies and other plants to give a gold colour to that cake. On Twelfth Night, you would cut into that cake, and you would say, that’s our celebration, that’s our tradition.

Beamish, The Living Museum of the North, winner of the Art Fund Museum of the Year 2025. Photo: © David Levene.

We have a brilliant approach to using food history as a huge part of telling the stories around the museum, either within the exhibit spaces themselves through the activities that our costume staff and volunteers are doing, through to what people can experience when they go into our bakery or into our sweetshop. We have two fish and chip shops – one is coal-fired, the other is a 1950s gas-operated one. The power of open-air museums is that you can be really in touch with your people to help to tell stories in ways that are meaningful for them across the year, which is why that decision of ours, to say, “Look, we’re going to tell the Christmas Story”, has been absolutely phenomenal in terms of visitor engagement and visitor reach, and it’s extremely popular. We have the same numbers coming through our Christmas weekends as we do during our summer holidays, so we know that that’s a winner for us.

NH: Beamish sketches the history of the region from the 1820s to the Victorian era and on towards the 1950s through an innovative educational programme, which brings learning to life with immersive experiences. Beamish offers a Victorian lesson where students can experience a traditional lesson of reading, writing and arithmetic delivered from a boarding school. How do you use the museum’s collections and spaces to inspire learning about science and industry?

RH: Your example there of a Victorian lesson is a brilliant one because it’s familiar to lots of people and it’s one of our sellouts. One of the first jobs I had at the museum was as a volunteer. Then I was an engager, and I was a learning assistant, and I used to deliver lessons in the Victorian school. I loved it because you go into first person to do those sessions. We do third-person engagement mostly at the museum, but in the Victorian lesson, you are in the first person and it’s brilliant. We have a programme of activities that is run through our learning and education team and programme, which is funded through the Reece Foundation. They have enabled us to develop well over a decade’s worth of work, engaging locally and further afield. We have brilliant programmes, such as one called Just One Spark, where children are immersed into one of our period areas and they learn about explosions, but we also talk to them about the history of coal mining. It’s a light-hearted, frivolous term, but actually you had to be careful when you worked underground because just one spark could have been a dangerous thing. So, we do a range of activities.

Beamish, The Living Museum of the North, winner of the Art Fund Museum of the Year 2025. Photo: © David Levene.

Before Covid, we were heading up to about 50,000-60,000 schoolchildren coming into the museum. After Covid, we’ve built that back up to about 45,000 and it’s still going up again, which is brilliant. We’re aware that our offer is amazing, but we’re very aware that our children coming to us, their schools, their backgrounds, they may find that challenging in terms of costs to get to the museum. We aim to attract funding to support groups coming in to enable them to pay for transport. Transport for schools is one of the highest barriers to accessing offers of out-of-classroom activities. We’ve set up an access fund, which we are encouraging our business friends to contribute to, so that when schools say, we want to come, we want to take part in a particular learning programme, but actually it’s a challenge for us, then we are able to say, well, how can we support you, what can we do? We have worked with other big businesses, who have given us free and supported opportunities for school groups to be able to come to the museum. My quest is that every schoolchild in the north-east of England has an opportunity to visit Beamish through funded and supported activity that they’re able to access. It saddens me and others I know to hear about the levels of poverty and child poverty in the north-east. If we can contribute in some way to enable children and young people to have experiences they wouldn’t ordinarily have access to, then that is something significant that we can do here at Beamish.

NH: Over the last two decades, the British government has reduced state funding for culture and encouraged museums to become more self-reliant and entrepreneurial. How do you find the current funding climate and how do you plan to use the award of £120,000 for future projects?

RH: At Beamish, as an independent museum, we have always been an entrepreneurial organisation, and we are always thinking about how we can be more creative but still being true to ourselves as fundamentally a museum with collections. We make sure our approach to commercial activity is in keeping with the museum, it’s in keeping with our morals, our ethics, the fact that we are a designated collection, and that we are a registered museum. We are very careful that the ways in which we diversify income are that there is clarity on how that income is generated. We have some exhibit spaces like our photographers’ space, which you can book, and you can pay to go into, but equally, it can still be an immersive experience for people. In places like the sweetshop, the bakery, the chip shops and our eateries, our tavern and places like that, people are going in because there is an expectation that there will be a financial transaction.

Beamish, The Living Museum of the North, winner of the Art Fund Museum of the Year 2025. Photo: © David Levene.

In terms of funding that we’ve had, we rely on our surplus year-on-year to develop the museum, but then whenever we have gone into big project times, particularly like the Remaking Beamish time, we have been pleased to receive big amounts of money from trusts, foundations and the lottery, but also in terms of business support. We have a brilliant business friends’ scheme and programme.

There is a big shift for museums and culture in terms of how you can still be fundamentally true to what you’re about and have that integrity while also thinking about what other things can bring income in to help those programmes of work be even better and sustainable for the future. For me, building that sustainability and that relationship with our business friends is about how we can work together to ensure the programmes can then develop into something, which is then bringing money back into the museum. The money we got when we won the award – £120,000 – is amazing. We were aware that one of the key reasons why we’ve won this award is because of our people. We are looking at how we would invest that money back into our people, back into our programmes, and make sure that it can become a foundation block. I mentioned that access fund we have, which is for young people and for groups externally, who are finding it challenging to be able to visit the museum because of barriers to transport and barriers to access. We will be putting some of that money into a fund, which we are developing, so that money is the starting point for young people being able to access the museum.

Beamish, The Living Museum of the North, winner of the Art Fund Museum of the Year 2025. Photo: © David Levene.

NH: How do you think the museum might make a difference to addressing the climate emergency?

RH: If you were looking at the museum from above, the pit village, the farm, the Georgian area, the 1900s town sort of come off this circular route of transport, which is about three miles in the round. Then when you are in the museum and you look around, there are about 400 acres around the museum and it’s down in a bowl of woodland, which encompasses the museum, which we are responsible for, which has waterways running through it. We have industrial heritage through those waterways and around the footpath. We have a responsibility, and we liaise with the local footpaths officer, ensuring that the footpaths that run through all those woodlands are accessible and free, because those are part of national footpath schemes. They are not wholly owned by the museum, but they are on our land. There’s that opportunity for us, first and foremost, to manage our woodland in a sustainable way, in a way which can hark back to traditional skills, whether that is horse logging, whether that is ensuring that we don’t use pesticides and different methods of managing weeds and species. We have ponds of scientific interest. We have three ponds, which are phenomenal. We have our responsibility ourselves, but we also have the absolutely spot-on opportunity for the stories about how we’ve got to where we are in terms of environmental sustainability. We work with Durham University, and we work with others, to think about how the museum can tell a story of where we’ve got to in terms of environmental responsibility. In the museum, we have steam engines that need to operate on coal. We have some coal fires, and we burn some wood in some areas, but we’re constantly thinking about how we can tell the stories without impacting on carbon and without impacting on our carbon footprint. We work with external bodies to think about how we can continue to tell the story in a tangible, hands-on, immersive way, but which isn’t going to increase our own footprint on the environment. There are some interesting discussions to have.