Mrinalini Mukherjee and works in progress at her garage studio. New Friends Colony, New Delhi, c1985. Courtesy of Mrinalini Mukherjee Foundation and Asia Art Archive. Photo: Ranjit Singh.

The Jillian and Arthur M. Sackler Wing of Galleries

Royal Academy of Arts, London

31 October 2025 – 24 February 2026

by BETH WILLIAMSON

I have seen the work of Mrinalini Mukherjee (1949-2015) in a number of exhibitions over the years, but this new exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts is a revelation. It is not solely about her work but, as the exhibition’s curator, Tarini Malik, explains, it is designed around her since she sits at an interesting crossroads, between modernism and the contemporary, between art school and the studio, and between inherited traditions and experimental practices. In this way, Mukherjee acts as a central pivot or viewpoint, from which we can better understand all these relationships and developments. Mukherjee’s work was made in conversation with family, friends, peers, teachers, institutions and places. Rather than look at her work in isolation, this exhibition shows it as it was made, as part of a community of artists, a network that enables a new story to be told, a story of South Asian art in its broadest sense as a space of dialogue. In this sense, as Malik points out, it is a story of plurality and the research behind the exhibition is informed by the ideas of two artists included here: Gulammohammed Sheikh, important for how we think about artistic modernity beyond the west, and Nilima Sheikh, whose thinking on traditional forms as living vocabularies runs through the exhibition. There is no nostalgia here.

Nilima Sheikh, Home, Land 2, 2024. Mixed tempera on Sanganer paper, 76.2 x 193.04 cm. Sunita and Vijay Choraria. © The Artist.

One of the most fascinating aspects of the exhibition is the importance given to the place of the art school in shaping practice. The sorts of intellectual and artistic lineages that Mukherjee was part of were equally as important as her heritage and family histories. This is about networks and shared learning that tended to occur around particular places. For that reason, the exhibition focuses on those places important to Mukherjee and her work – Santiniketan, Baroda (Vadodara) and New Delhi – as well as the broader avant garde.

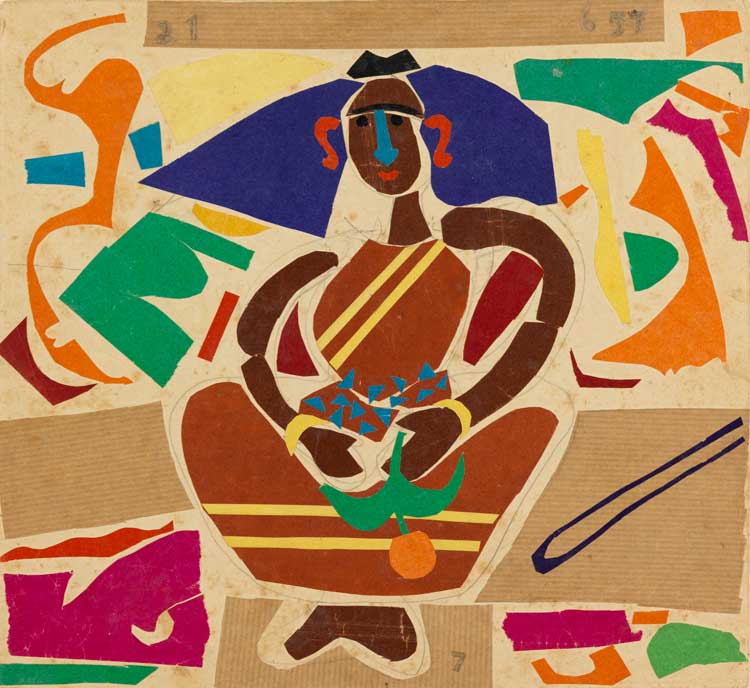

Benode Behari Mukherjee, Lady with Fruit, 1957. Paper and graphite on paper, 25.7 x 28 cm. Tate: Purchased with funds provided by the South Asia Acquisitions Committee 2015. Photo: © Tate. Courtesy of Mrinalini Mukherjee Foundation.

Santiniketan, founded in 1901 by Rabindranath Tagore, is where, in 1921, the university of Visva-Bharati (meaning community of the world within India) was established, two years after the Institute of Fine Arts, Kala Bhavana was set up, in 1919. Among the institute’s most influential teachers was Benode Behari Mukherjee, Mukherjee’s father. It was at Santiniketan, too, that Mukherjee’s mother, Leela Mukherjee, developed her own sculptural and graphic practice. Both Mukherjee’s parents drew on global influences. While Leela looked to influences from West Africa and Mexico, blended with Indian and Nepalese folk art, Benode’s collages and paintings drew on his travels in China and Japan. It was here that Mrinalina grew up with an interest in botany, describing the natural forms of plants for her father who was visually impaired and blind by the age of 53. Her childhood understanding of the natural curves and folds reappeared much later in her hemp sculptures such as Adi Pushp II (1998-99) with its simultaneous botanical and human forms and energy. In later bronze works, such as Forest Flame IV (2009), her scale and ambition did not get in the way of exquisitely carved foliage and blossoms.

Mrinalini Mukherjee, Forest Flame IV, 2009. Bronze, 175.3 x 88.9 x 68.6 cm. Taimur Hassan Collection. Photo: Humayun Memon. Courtesy of Mrinalini Mukherjee Foundation.

Baroda was home to Maharaja Sayajirao University, founded in 1949, and the Faculty of Fine Arts established in 1950, three years after Partition. Mukherjee joined the cohort of 1965, training under KG Subramanyan. He encouraged students to ignore the hierarchies between art and craft perceived in western art and to look instead to the plurality in Indian cultural histories. In one aspect of Subramanyan’s own practice, he engaged deeply with Indian textile traditions. For him, textiles were a living art form, advocating for the place of craft in a swiftly changing world. Yet as Mukherjee observed in 1994, her interest in craft was sparked much earlier: “From both my parents, as from the ideological orientation of Santiniketan, I inherited a respect for craft – craft as a process, and for the craft object.” Still, it was Subramanyan’s encouragement that led Mukherjee to look to local indigenous materials such as jute and hemp, modifying the ancient Arabic knotting technique of macrame to enable her to create her monumental sculptures. Mukherjee’s close friends Gulammohammed Sheikh and Nilima Sheikh also studied with Subramanyan in Baroda, each bringing her into contact with their interests. In Gulammohammed’s case Indian miniatures, and medieval and Renaissance painting, came together with his political commitments. For Nilima, her feminist visual language layered historical and literary references across cultures to address questions of memory and place.

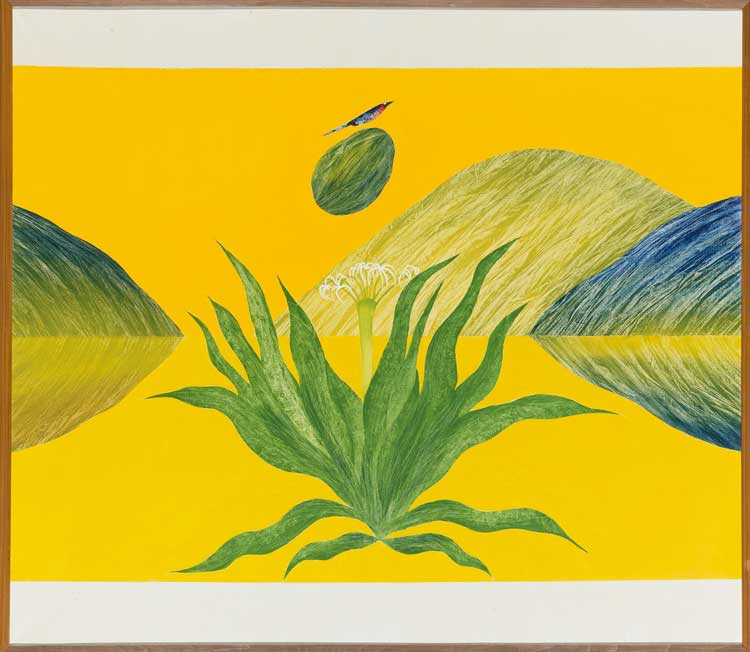

Jagdish Swaminathan, Untitled (Lily by my Window), circa early 1970s. Oil on canvas, 106.7 x 121.9 cm. Private collection, Switzerland. Photograph Courtesy of Sotheby’s, Inc. © 2025. © J. Swaminathan Foundation.

It was in Delhi in the 1970s that Mukherjee entered a community of artists and intellectuals concerned with making art in an independent nation. Jagdish Swaminathan was at the heart of this creative community and it was he who advocated for a plural modernism. Gulammohammed Sheikh and Nilima Sheikh continued to be important for Mukherjee at this time. Garhi Studios, founded in 1976, became a significant site of exchange for these artists who were joined by Mukherjee’s mother. Leela focused her production at this time on bronze sculptures and prints while nurturing mentorship and friendship. Garhi Studios functioned as a vital community, a space of exchange between older and younger generations of artists who shared knowledge, experimented with materials and worked together as a collective at a time when institutional and political structures were shifting.

Mrinalini Mukherjee, Jauba, 2000. Hemp fibre and steel,143 x 133 x 110 cm approx. Tate: Presented by Amrita Jhaveri 2013. Photo: © Tate. Courtesy of Mrinalini Mukherjee Foundation.

Mukherjee’s ceramic works are particularly special. It was following her involvement in a workshop organised by the Foundation of Indian Artists in 1995 that she began to create bulbous vegetal forms glazed in visceral colours, such as the red of Earthbloom (1996). Rolling clay on to fabrics or beds of foliage, Mukherjee transferred the textures and imprint to the clay. As with the hemp sculptures, these ceramic works are equally vegetal and human. This perhaps reaches a limit case of sorts (a human figure seemingly made entirely of vegetal forms) in the astonishing work Night Bloom II (1999-2000). It was created during a residency in the Netherlands, and Mukherjee layered slabs of clay to create a sculpture suggestive of a female figure sitting in the lotus position. Its myriad surfaces shift between glazed and unglazed, between earth and colour, between fold and surface, between figure and foliage, and between texture and smooth finish. In some respects, this gestures back to a seated figure by her mother, Schematic Seated Figure (1950-89), if with very different materials and motivations.

Leela Mukherjee, Schematic Seated Figure, c1950s-80s. Wood, 36.8 x 21.6 x 7.6 cm. Taimur Hassan Collection. Photography: Justin Piperger. Courtesy of Mrinalini Mukherjee Foundation.

Ultimately, this exhibition brings to the fore many artists hardly known in the UK. Mukherjee’s pivotal role in this community makes for a rich and multifaceted story that is only just beginning to be told. Research-rich and visually thrilling, this is surely a first important step in sharing the life and work of this important group of south Asian artists. The plurality of modernism has never been clearer and I can’t wait to discover what comes next.

• A major retrospective of Mrinalini Mukherjee’s work, built on this exhibition, will be shown at the Hepworth Wakefield from 23 May to 25 October 2026.