Anna Ancher, A Field Sermon, 1903. Courtesy of Skagens Museum.

Dulwich Picture Gallery, London

4 November 2025 – 8 March 2026

by ANNA McNAY

Thickly daubed orange rectangles glow warmly from a dove-blue canvas; next to this, silvery panes stretch out across a blue wall and a striped carpet on the floor, the silhouette of a plant reaching tall, elongated in its reflection on the wall.

As the title of this exhibition intimates, this is a show about light, as evidenced by these and a great many other of the works on display; but, as well as that, it is a show about women at work, both explicitly depicted on the canvases, busy at their traditional chores, and implicitly expressed in the persona of the artist at her easel who produced this delightful body of paintings. That artist is Anna Ancher (née Brøndum, 1859-1935).

Although not a known name in the UK, Ancher does not deserve to be tagged as one of the many “recent rediscoveries” of female artists, since, in her home country of Denmark, she achieved success during her lifetime and remains well-known. Born in the village of Skagen, on the Skaw peninsula, Ancher grew up, the daughter of the only hoteliers in the vicinity, getting to know the many visiting artists as they came to paint the dramatic scenery where the North Sea meets the Baltic, and the sand dunes are littered with the remains of many shipwrecks. Spotting precocious talent in the young girl, the artists encouraged her and gave her lessons; at the age of 15, she was sent to Copenhagen to attend Vilhelm Kyhn’s school for female painters (as the Danish Academy still did not accept women). She went on to marry the painter Michael Ancher, and the couple became the beating heart of the artist colony that formed in Skagen.

Anna Ancher, A Girl in the Garden in Summertime. Skagen, 1914. Image courtesy of Skagens Museum.

In spite of the many travels Ancher undertook with her husband, and the six months she spent studying under Pierre Puvis de Chavannes in Paris, she remained loyal to her home and its inhabitants as the subjects for her work. She painted her mother, her sisters and her daughter in the variously coloured rooms of the hotel, as well as painting local women, and the odd man, including the early Old Man Whittling Sticks (1880), with which she made her formal debut as an artist when it was selected by jury to show in the annual spring exhibition at Charlottenborg, Copenhagen. It is thought the subject could be Lars Gaihede, an enormous, ugly man with an oversized toe, who was popular among the artists, despite the rumour that he gave several of them fleas while sitting for them.

Another early work on show in the Dulwich Picture Gallery exhibition is the self-portrait from 1879 – the only known self-portrait by the artist – which was most likely made the year after she had finished her training with Kyhn. It shows her distinctive profile with a broken-bridged nose and, as the co-curator, Helen Hillyard, says: “There is quiet self-confidence to it … this sort of piercing gaze.”

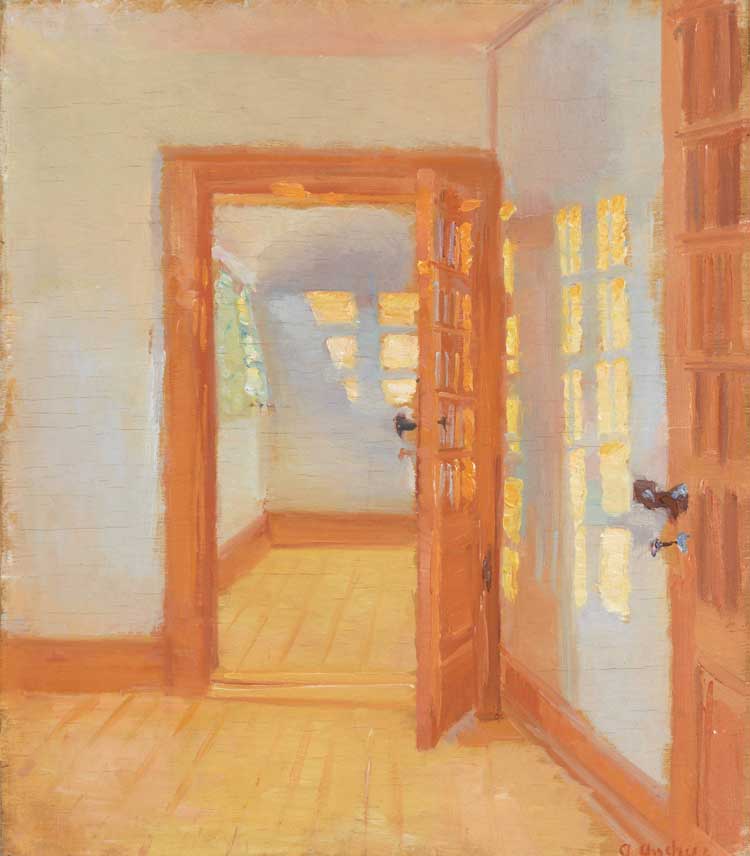

Anna Ancher, Interior. Brøndum's Annex, 1916. Image courtesy of Skagens Museum.

The focus of the first room, aside from these two early works, is Ancher’s handling of light, and there are works from a wide range of dates. The aforementioned orange rectangles belong to Evening Sun in the Artist’s Studio at Markvej (after 1913), one of 41 works on loan from the Skagens Museum. This is the most brazen and abstracted study of light (one of few canvases without a figure), and it is delicious in its richness and the complementarity of its tones. The painting is shown unframed, having never been exhibited before, and this rare opportunity to enjoy the sides of an Ancher canvas is to be savoured. The similar Interior. Brøndum’s Annex (c1916) is a little more complex with two door frames added into the composition. Hillyard compares both these works to Monet’s Impression, Sunrise (1872), which Ancher would have seen in Paris. It is worth noting also that it was Ancher who encouraged her husband to be more experimental, not vice versa.

Anna Ancher, Sunlight in the blue room, 1891. Oil on canvas. Image courtesy of Skagens Museum.

Sunlight in the Blue Room (1891, also described above) is labelled as one of Ancher’s masterpieces, and, indeed, it is remarkable in its use of diagonals – especially the stripes on the carpet – to intersect with and articulate the light falling through the windows of the blue room in Brøndum’s hotel. At the time, this work was criticised for being “too modern”, and one critic described “the poor child’s yellow hair [being] eaten up by the sun to the scalp”,1 whereas, to me, this delightful muddle of gold suggests the tousled hair of Ancher’s young daughter, Helga, busy with her knitting. Interestingly, Ancher was intrigued by the effects of light at different times of day, and, by making multiple paintings in the same rooms, she could explore the interaction of different light with the variously coloured walls. (In this way also, she worked in a similar vein to Monet.) While the blue of this room can only be described as dreamy, it also appears in A Woman Knitting. Evening Light (1919), where, against the sitter’s bright-red dress, and at this later time of day, it is rendered almost violet.

Anna Ancher, The Maid in the Kitchen, 1883–86. Courtesy of The Hirschsprung Collection.

The next room is filled with pictures of women at work – sewing, knitting, plucking birds and harvesting. The Maid in the Kitchen (1883-86) – made the year after Ancher travelled to Berlin, Dresden, Vienna and Munich – recalls Dutch 17th-century painting, in particular Johannes Vermeer. The painting exquisitely captures light, not only coming through the windows on the fluttering curtains, but in a swathe of peach on the wall to the maid’s left. Ancher also wrote in her letters about how Rembrandt’s works created a “glow” deep within her.

Women Plucking Chickens (1902) and its neighbouring Plucking the Geese (1904) provide an interesting contrast and further example of Ancher returning to the same motif. Both works show a group plucking birds, collecting the feathers in baskets. Made just two years apart, they are, however, quite different in their approaches. The earlier of the two works has a darker palette, with a greater focus on the contrast of light and shade. In this regard, the work is more reminiscent of a Dutch genre scene. In Plucking the Geese, however, Ancher refined her approach, rendering the scene – albeit with a near-identical composition – far lighter and airier.2 The much whiter feathers of the geese make the picture easier to decipher, as well.

Four works in the exhibition, on loan from Sandi Toksvig, are not by Ancher, but aim to provide comparison with some of her contemporaries. Certainly, the paintings by Emilie Mundt, Marie Luplau, Louise Bonfils and Marie Sandholdt are all more academic and less experimental. They lack the charm and inner glow of Ancher’s work. To my mind, a comparison might better have been drawn with the work of her fellow Skagen artist PS Krøyer, who painted similarly ethereal scenes of sunset on the beach, depicting what he termed “the blue hour”, when the sea and sky seem optically to merge. This can be observed most beautifully in Ancher’s Boats at Sønderstrand, Moonlight (c1883), in which a simple, circular moon, with a couple of dry strokes of paint capturing the light around it, hangs above a horizon only really discernible because of the impasto strokes of reflected light on the water below. In the daytime scene of Children Playing on Skagen Beach (c1905), the sea is several shades darker than the sky, and the sky has more visible brushstrokes, suggesting a gentle breeze, while the sea is capped here and there with white crests.

A question raised by the curators is how Ancher managed to succeed when her contemporary female painters didn’t (at least not to the same degree)? The answer is that she had immense familial support. As one of six siblings – the others of whom all worked in the hotel – Ancher was never short of a hot meal or a babysitter. Indeed, Ancher’s female contemporaries were scathing of her for achieving her success not in spite of, but thanks to and within the patriarchy.

Accordingly, Ancher’s mother was her most common subject, with four portraits – of many more that exist – included here. As well as embodying their closeness, they show Ancher’s concern with death, latterly in the death portrait (1916) of her mother, in which the elderly woman is shown to be peacefully at rest, but also with the earlier Mrs Brøndum at the Bed of her Daughter Agnes (1910), in which her mother sits with Ancher’s dead elder sister. In this work, Agnes is but barely sketched in, and one of the exhibition installers asked whether it might not be because the artist couldn’t bear to spend too long with her. No definitive answer can be given.

Anna Ancher, The Harvesters, 1905. Image courtesy of Skagens Museum.

Despite her success, Ancher’s work is often devalued as “domestic” and “feminine” in contrast to the large-scale narrative paintings of her male peers. However, if you haven’t already been convinced otherwise, the large A Field Sermon (1903) refutes this. It calls to my mind the similar Gottesdienst im Freien (Service in the Open Air) (1893) by Fritz Mackensen of the north German Worpswede colony. Whether or not Ancher would have been aware of this, however, I am unsure. Another beautiful example to counteract these labels is Harvesters (1905), a frieze-like procession of workers through the wheatfield, painted in a glorious pale blue and yellow, far paler than Van Gogh’s wheatfield colours – his are hot and Mediterranean, these are cool and Scandinavian.

In the final room, the painting Grief (1902) is exceptional and stands out from the rest due to its symbolist style. An old lady in black kneels, hands interlaced in prayer, facing a naked young woman, whose long blond mane acts as a cloak. Between them is a cross like a grave marker, only seemingly out on the moor. How this is to be interpreted also remains open. It could be another self-portrait, depicting a younger and older Ancher, coming to terms with her family’s traditional ways and her avant garde life as a modern artist, but, equally, it could represent the younger and the older generation more widely, or, artistically speaking, tradition and modernity. As Hillyard concludes: “We see Ancher looking back in order to move forwards, using lessons from the past to push new boundaries, while simultaneously incorporating developments at the cutting-edge of artistic practice.”3 This is as much a description of her wider practice as it is of this one remarkable painting.

References

1. Life in a Sunbeam by Mette Harbo Lehmann in Anna Ancher: Painting Light, Dulwich Picture Gallery, exh cat, pages 45-48.

2. ‘The Desert between Two Roaring Seas’: Anna Ancher and Skagen by Helen Hillyard in exh cat, op cit, page 125.

3. Looking Back, Looking Forwards: Anna Ancher’s Artistic Influences by Helen Hillyard in exh cat, op cit, page 87.