Haus der Kunst, Munich

4 September 2020 – 14 February 2021

by JOE LLOYD

Of the several supposed paradises that appear in Paradise Edict, the first might be the purest. Five paintings hang above a stairwell, elevated so that one has to crane upwards to see them. Each depicts animals amid thriving vegetation. They are not quite in the state of nature. The corruptions of human society are present even here. One, Sykes Monkey, sits smiling atop an ostrich, asserting dominance over his avian cousin. Another primate walks around in a leopard-print bra, while a third reclines nude, modesty concealed with a suggestive bunch of bananas. If there was once an age of innocence, it has now lapsed.

Michael Armitage, Baboon, 2016. Oil on Lubugo bark cloth, 150 x 200 cm. © Michael Armitage. Photo © White Cube, Ben Westoby.

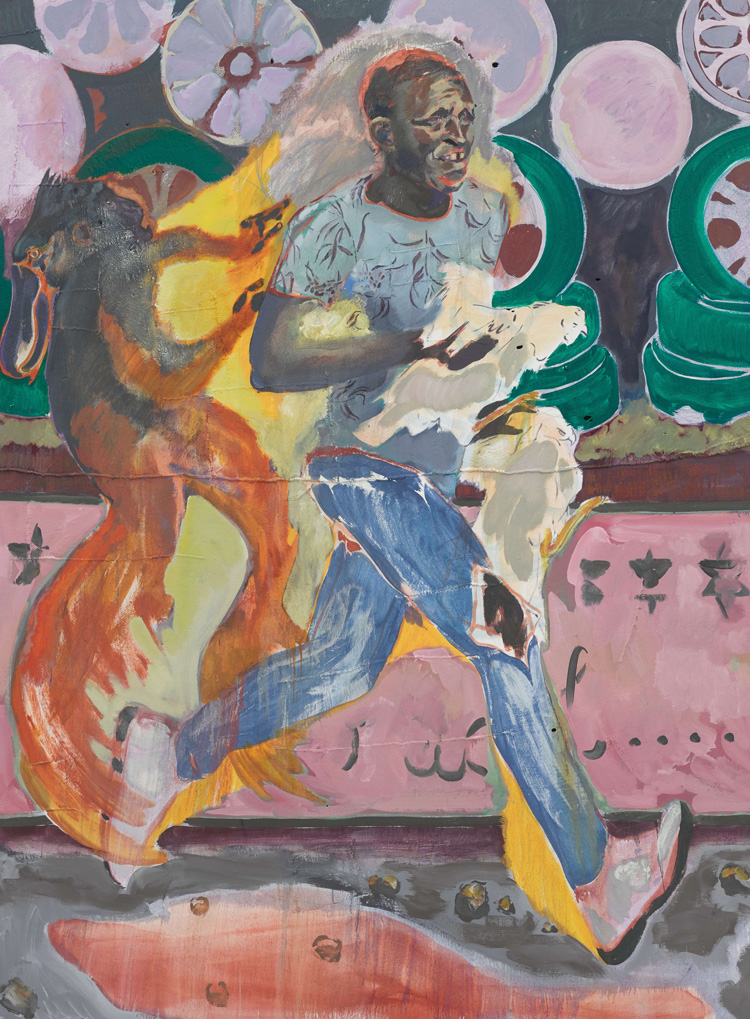

At once seductive and sinister, the world of British Kenyan painter Michael Armitage (b1984, Nairobi) is a fallen one, shot through with violence and pain. It is a place where myth and folklore have bled into contemporary East Africa. A woman gives birth to a baby donkey, while marvelling at a washing machine in the sky. A shower of blood falls over a latter-day Midas, lapped by a cheetah. A chicken thief, face defiant (Armitage is particularly good at faces) is pursued by a flaming ape-bird hybrid. This vacillation between realism and symbolism marks Armitage as an artistic descendant of Paul Gauguin, as do his coruscating colours, seductive even in his slighter works. But unlike that priapic post-impressionist, Armitage acknowledges from the start that the exotic is a troubling construction, projected from Europe as it sought to subjugate the world.

Michael Armitage, The Chicken Thief, 2019. Oil on Lubugo bark cloth 78 3/4 x 59 1/16 in. (200 x 150 cm). © Michael Armitage. Photo © White Cube, Theo Christelis.

Paradise Edict is the largest exhibition of Armitage’s works to date. It comes just half a decade after his first solo show at the White Cube. His ascent has been rapid. in 2017, drew universal praise. It also prompted a hundred comparisons with the Scottish-born Peter Doig, among the most renowned figurative painters at work today. And, like Doig before him, Armitage’s paintings quickly became hot property on the commercial art market. Last year, one sold at Sotheby’s for more than 20 times its asking price, after appearing in the Venice Biennale. Several of the works in Munich come loaned from the first tier of super-collectors.

It is easy to see why Armitage’s art holds so much appeal to these buyers. His is a new voice with a distinct perspective and he works in a well-trodden idiom. But his art amounts to more than a postscript on its predecessors. Armitage’s works have an aqueous brilliance of their own. This stems in part from his tools. Armitage applies gossamer light layers of oil paint, colours loaned from a dream, on to a canvas of lubugo. This substance, bark sustainably stripped from Ugandan fig trees, provides a rugged counterpoint to the paint’s incorporeality. Irregularly shaped pieces are stitched together, adding a textual dimension to each artwork.

Michael Armitage. Paradise Edict, 2019. Installation view, Haus der Kunst, Munich, 2020. Photo: Markus Tretter.

To this, Armitage adds a second dichotomy, the melding of mythological scenes with those drawn from observed experience. Sometimes several events occupy the same physical space of the picture field, dissolving mirage-like into others. Paradise Edict (2019), the exhibition’s title exhibit, crams several narratives into one lush landscape. There is a contemporary Adam and Eve, the latter striding forward with a cowed, circumspect expression. Behind her, serpentine forms curl and snarl. Above, feet begin their descent from the sky, perhaps cast down from heaven. And then, occupying the same whirls of paint, there is a gory scene reminiscent of Francisco Goya’s Saturn Devouring His Son (c1819-1823), a screaming man grabbed by two firm hands.

Michael Armitage, Accident, 2015. Oil on Lubugo bark cloth, 170.2 x 221 cm. © Michael Armitage. Photo © White Cube, George Darrell.

There are at least two different paradises here: the biblical Eden and the colonial-era fantasy of an uncorrupted idyll, as epitomised by Gauguin. Does the edict stem from God, from Saturn, or from Armitage’s artistic predecessors in the representation of “exotic” scenes? The weight of art history exerts a heavy pressure on Armitage’s work, and not just because of its fauvist radiance. The majestic Exorcism (2017), which depicts a Tanzanian ceremony of exorcism, interpolates figurative groups from Edgar Degas’ Young Spartans Exercising (c1860) and Édouard Manet’s Music in the Tuileries (1862) while appearing derivative of neither. Armitage is restoring East African life to the prestige of these “western” forms. But he is also working to reach these masters of the past, absorbing influences in refining his work.

Armitage’s influences are not only western. Earlier this year, he established the Nairobi Contemporary Art Institute, dedicated to the preservation and dissemination of East African art. Paradise Edict’s capacious final chamber showcases six of the region’s artists, in what amounts to a tantalising preview of the institute’s mission. Though varied in style – from Meek Gichugu’s outrageous obscenities to Elimo Njau’s sun-washed landscapes, dotted with hidden eyes – elements of Armitage’s style can be seen in all of them. The late Ugandan Jak Katarikawe, once dubbed the Marc Chagall of Africa, depicts animals with the same humanity, while the Kenyan Asaph Ng’ethe Macua, a specialist in gouache, pre-empts Armitage’s magical realism. All six artists deserve more extensive attention.

Michael Armitage. The promised land, 2019. Installation view, Paradise Edict, Haus der Kunst, Munich, 2020. Photo: Markus Tretter.

Placing these artists at the end prevents them from being relegated to a sideshow, footnotes in the Armitage story. But Paradise Edict climaxes two rooms before them, with a recent series that sees Armitage weave his interest in portrait, figurative groups, landscapes and animals into cohesive wholes. The Kenyan Election cycle (2018-19) comprises eight paintings made in response to the civil unrest after that country’s contested 2017 presidential election. In Armitage’s hands, protest is imbued with an ecstatic energy, one that sometimes erupts into violence. The Promised Land (2019) shows a peaceful protest degenerate with the firing of a Molotov cocktail; a baboon sits in the centre, seemingly impassive in the face of the fracas around it. There is still surrealism: in Accomplice (2019), a trio of figures floats above a tyre fire, while Pathos and the Twilight of the Idle (2019) turns a sling-carrying woman into a symbolist allegory. But Armitage’s clearest vision of Kenya as it is today, vibrancy and liveliness coexisting with poverty and political chaos, is his most satisfying to date — and might presage great things.

Audio tour of Michael Armitage: Paradise Edict at Haus der Kunst, Munich.

Abstract Erotic: Louise Bourgeois, Eva Hesse, Alice Adams

A groundbreaking New York show from 1966 is brought back to life with the work of three women whose ...

Jeremy Deller – interview: ‘I’m not looking for the next thing. I...

How did he go from asking a brass band to play acid house to filming former miners re-enacting a sem...

Encounters: Giacometti x Huma Bhabha

The first of three exhibitions to position historic sculptures by Alberto Giacometti with new works ...

The Parisian scenes that Edward Burra is known for are joyful and sardonic, but his work depicting t...

The 36th Ljubljana Biennale of Graphic Arts: The Oracle

Surprising, thrilling, enchanting – under the artistic direction of Chus Martínez, the works in t...

It’s Terrible the Things I Have to Do to Be Me: On Femininity and Fame ...

In a series of essays about pairs of famous women, the cultural critic Philippa Snow explores the co...

Paul Thek: Seized by Joy. Paintings 1965-1988

A rare London show of elusive queer pioneer Paul Thek captures a quieter side of his unpredictable p...

This elegantly composed exhibition celebrates 25 years’ of awards to female artists by Anonymous W...

The first of its kind, this vast show is a stunning tour of the realism movement of the 1920s and 30...

Maggi Hambling: ‘The sea is sort of inside me now … [and] it’s as if...

Maggi Hambling’s new and highly personal installation, Time, in memory of her longtime partner, To...

Caspar Heinemann takes us on a deep, dark emotional dive with his nihilistic installation that refer...

Complex, multilayered paintings and sculptures reek of the dark histories of slavery and colonialism...

Shown in the context of the historic paintings of Dulwich Picture Gallery, Rachel Jones’s new pain...

William Mackrell – interview: ‘I have an interest in dissecting the my...

William Mackrell's work has included lighting 1,000 candles and getting two horses to pull a car. No...

Marina Tabassum – interview: ‘Architecture is my life and my lifestyle...

The award-winning Bangladeshi architect behind this year’s Serpentine Pavilion on why she has shun...

A cabinet of curiosities – inside the new V&A East Storehouse

Diller Scofidio + Renfro has turned the 2012 Olympics broadcasting centre into a sparkling repositor...

Plásmata 3: We’ve met before, haven’t we?

This nocturnal exhibition organised by the Onassis Foundation’s cultural platform transforms a pub...

Ruth Asawa: Retrospective / Wayne Thiebaud: Art Comes from Art / Walt Disn...

Three well-attended museum exhibitions in San Francisco flag a subtle shift from the current drumbea...

This dazzling exhibition on the centenary of John Singer Sargent’s death celebrates his versatile ...

Through film, sound and dance, Emma Critchley’s continuing investigative project takes audiences o...

Rijksakademie Open Studios: Nora Aurrekoetxea, AYO and Eniwaye Oluwaseyi

At the Rijksakademie’s annual Open Studios event during Amsterdam Art Week, we spoke to three arti...

AYO – interview: Rijksakademie Open Studios

AYO reflects on her upbringing and ancestry in Uganda from her current position as a resident of the...

Eniwaye Oluwaseyi – interview: Rijksakademie Open Studios

Eniwaye Oluwaseyi paints figures, including himself, friends and members of his family, within compo...

Nora Aurrekoetxea – interview: Rijksakademie Open Studios

Nora Aurrekoetxea focuses on her home in Amsterdam, disorienting domestic architecture to ask us to ...

Kiki Smith – interview: ‘Artists are always trying to reveal themselve...

Known for her tapestries, body parts and folkloric motifs, Kiki Smith talks about meaning, process, ...

Frank Auerbach, Britain’s greatest postwar painter, has a belated German homecoming, which capture...

How Painting Happens (and why it matters) – book review

Martin Gayford’s engrossing book is a goldmine of quotes, anecdotes and insights, from why Van Gog...

Jonathan Baldock – interview: ‘Weird is a word that’s often used to...

As a Noah’s ark of his non-binary stuffed toys goes on show at Jupiter Artland, Jonathan Baldock t...

Helen Chadwick: Life Pleasures

Helen Chadwick’s unwillingness to accept any binary division of the world allowed her to radically...

Catharsis: A Grief Drawn Out – book review

To what extent can the visual language of grief be translated? Janet McKenzie looks back over 20 yea...