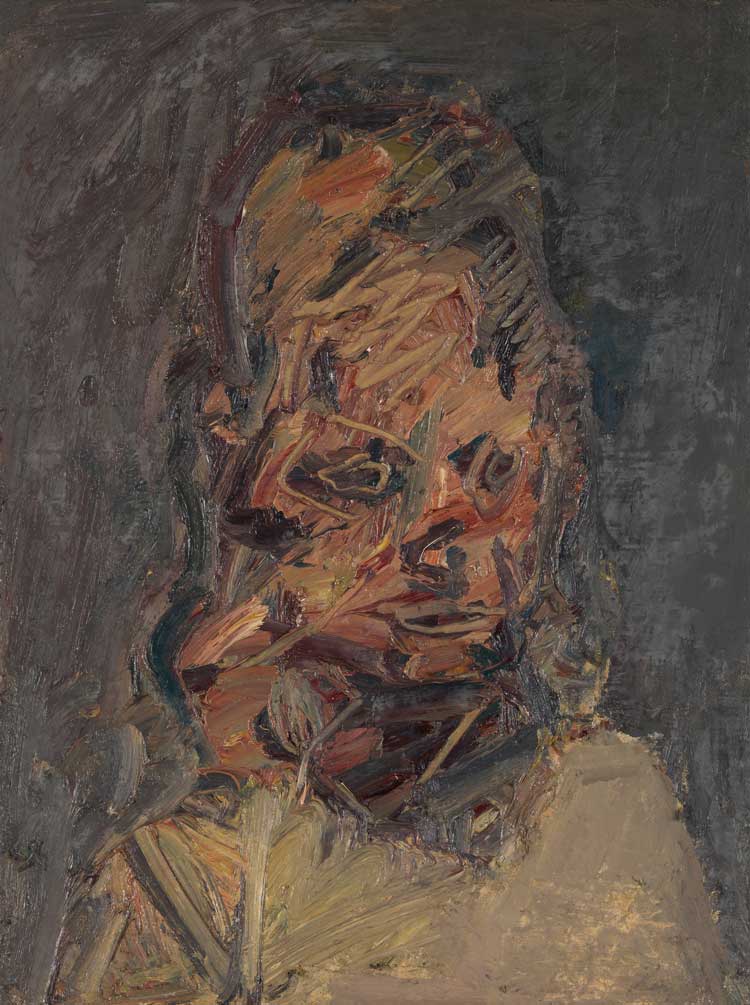

Frank Auerbach. David Landau Seated, 1995 (detail). Oil on canvas, 26 x 26 in (66 x 66 cm). Private Collection. © The Estate of Frank Auerbach. Courtesy Michael Werner Gallery.

Michael Werner Gallery, Berlin

3 May – 28 June 2025

by JOE LLOYD

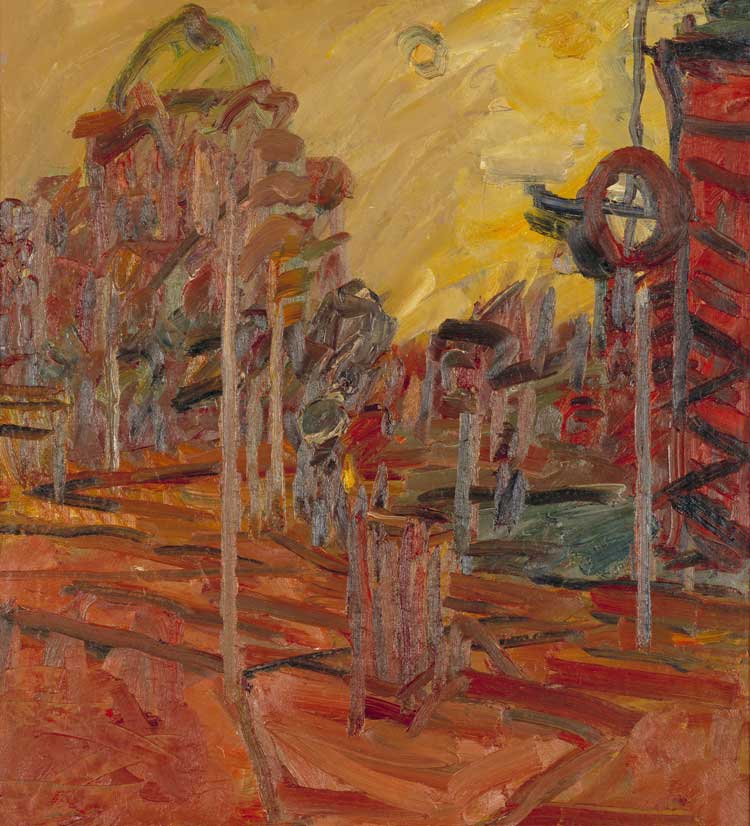

Frank Auerbach was a master of painting thinly and thickly at once. His canvases are often covered in wide, finger-thickness brushstrokes. They can dart around to define the contours of a face or the outline of a body. In his landscapes, they delineate buildings, railings, vegetation and the play of light. Yet, with the exception of his early works, where so much paint is layered that finished works almost resemble reliefs, these broad dashes of colour are often lightly applied. Often, they are thin in the middle and thick on the edges, like the seal on a letter. Sometimes, the grain of the canvas can be seen beneath the paint. This combination between light and heavy is one of the things that makes his paintings seem so miraculous, whether he is abstracting Rembrandt, depicting a reclining nude, or capturing the almighty clutter of his studio.

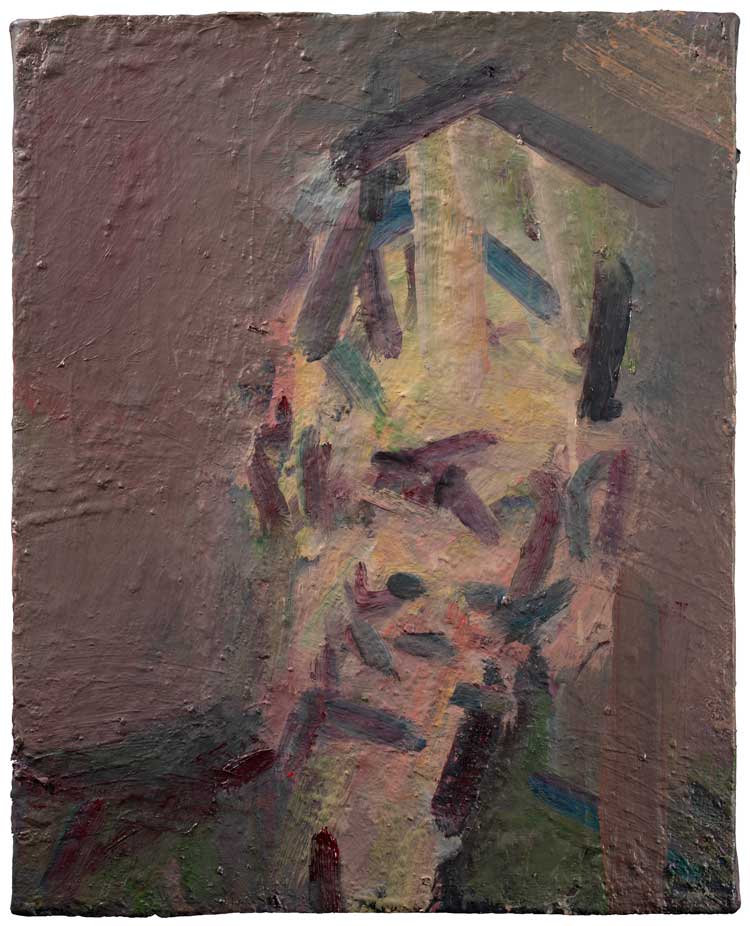

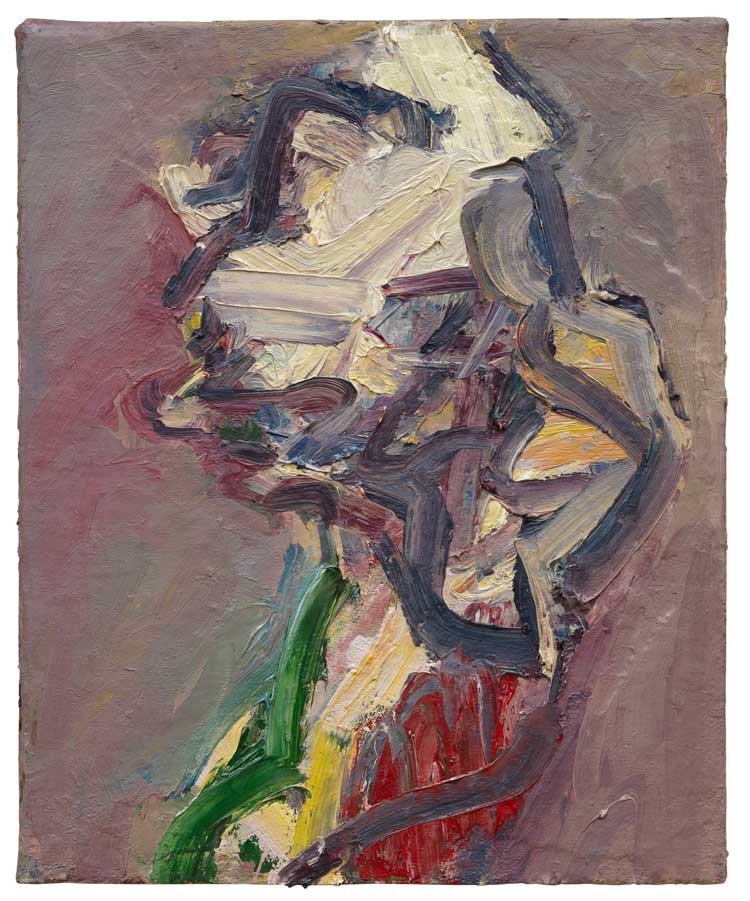

Frank Auerbach. Head of William Feaver, 2021-23. Oil on canvas, 20 1/2 x 16 in (52 x 40.5 cm). © The Estate of Frank Auerbach. Courtesy Frankie Rossi Art Projects and Michael Werner Gallery.

These subjects all feature in Auberach’s exhibition at Michael Werner Gallery in Berlin: two floors of a genteel early 20th-century apartment building. It is the first exhibition of Auerbach’s work in Berlin, and among the few times his work has been exhibited in Germany. Michael Werner Gallery and the curator Catherine Lampert (herself one of Auerbach’s sitters: we see her three times, in 1997, 1998 and in 2005, rendered here in stripes of pink, yellow and greenish grey) have corralled a remarkable selection of paintings and drawings from throughout Auerbach’s decades-long practice, presented in a roughly chronological array across two floors. They are displayed particularly gracefully. The earliest work, Study after Deposition by Rembrandt II (1961), greets us at the end of a long hallway; we can turn right, and through an open wood and glass door, to see Chimney in Mornington Crescent – Winter Morning (1991), where the titular smokestack gains a church-like grandeur.

Frank Auerbach. Mornington Crescent – Early Morning, 1999. Oil on canvas, 50 x 45 1/4 in (127 x 115 cm). Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebaek, Denmark. Acquired with support from The New Carlsberg Foundation. © The Estate of Frank Auerbach. Courtesy Michael Werner Gallery.

Auerbach, who died last November aged 93, gained an aura of legend during his lifetime. He was a monomaniac perfectionist ensconced in his studio in Camden, north London, painting the same landscape or portrait over and over again, scraping off the paint so that the floor and his trousers were bespattered with splotches of colour. He was a workaholic, painting 364 days a year, breaking only for an annual trip to the seaside, until that too became too much of a distraction. He showed little interest in the world beyond the north London areas of Primrose Hill and Mornington Crescent. Except for his regular sitters, the people who appear in his work are incidental, the result of early morning sketching, whether a jogger panting down Hampstead Road (2010) or Munch-faced phantasms emerging from St Pancras (1978-79). Everything was secondary to his project of painting. He did not even attend his own exhibitions, leaving that to others.

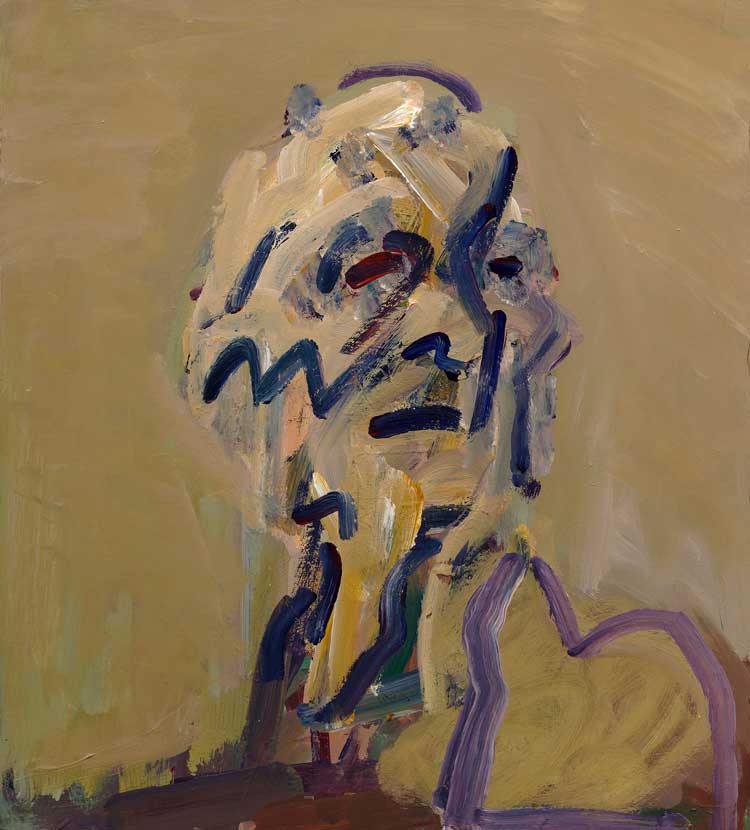

Frank Auerbach. Self-Portrait, 2024. Acrylic on board, 20 x 18 in (51 x 45.5 cm). © The Estate of Frank Auerbach. Courtesy Frankie Rossi Art Projects and Michael Werner Gallery.

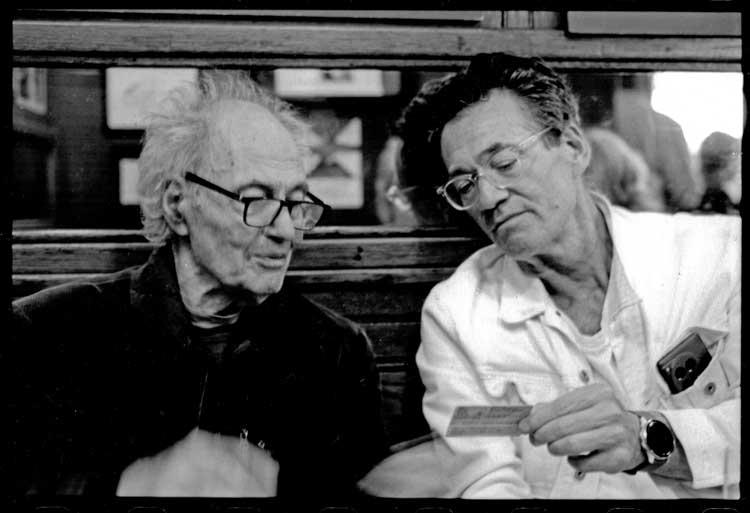

This Auerbach legend combines elements of truth with speculation. Accounts by his intimates have depicted a keen conversationalist with a ripe sense of humour. According to his son, the film-maker Jake Auerbach, he was fascinated with Old Hollywood films and light entertainers including Ken Dodd and Max Miller. Yet the myth of the dour recluse has persisted. This partly relates to Auerbach’s background. He was born in 1931 in Berlin into a Jewish family, then sent to England in 1939 with the writer Iris Origo’s sponsorship. His parents later perished in Auschwitz. It has become easy to assume his practice stems from a trauma over this loss and displacement: painting the same individuals over and over again, as if to prevent them from vanishing.

Frank Auerbach and the filmmaker Jake Auerbach, 2024. © The Estate of Frank Auerbach. Courtesy Jake Auerbach. Photo: Nicola Bensley.

This idea was further propagated by the German writer WG Sebald, who wrote him into his 1992 book The Emigrants as the fictional Max Ferber (Max “Aurach” in the first edition). Ferber embodies all the assumptions made about Auerbach. His is transfixed by the pain and suffering in Matthias Grünewald’s Isenheim altarpiece. “What is certain, though, is that mental suffering is effectively without end. One may think one has reached the very limit, but there are always more torments to come. One plunges from one abyss into the next.” Like Cézanne when confronted with Zola’s The Masterpiece (1885), Auerbach was not amused. He called Sebald’s project “repellent” and “a narcissistic undertaking”.

Frank Auerbach. Head of Catherine Lampert, 1998. Oil on board, 30 x 22 in (76.5 x 56 cm). Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebaek, Denmark. Acquired with support from The New Carlsberg Foundation. © The Estate of Frank Auerbach. Courtesy Michael Werner Gallery.

Auerbach never publicly revealed any trauma from his background. Which is not to say it is not there. We find it difficult to imagine anyone not suffering after enduring what Auerbach did. When asked about his childhood in an interview that appears in his son’s intimate new film, Frank Auerbach: Life and Death, the artist recalls his joy at the flurry of activity in his Kentish boarding school rather than anything lost. He stressed that he faced the present. “I absolutely believe,” he once said, “that you keep forging on, forwards, and that if you look back, you turn into a pillar of salt.” And he cast the repetition in his work as a grasping towards a truth. He told Robert Hughes: “To paint the same head over and over leads you to its unfamiliarity. Eventually you get near the raw truth about it, just as people only blurt out the raw truth in the middle of a family quarrel.”

Frank Auerbach. Catherine Lampert – Profile, 1997. Oil on canvas, 22 x 18 in (56 x 46 cm). Private Collection. © The Estate of Frank Auerbach. Courtesy Michael Werner Gallery.

Even here in Charlottenburg, in a turn of the century apartment that resembles the one nearby where Auerbach himself grew up, the strength of Auerbach’s painting forces you to consider his works as individual pieces. They resist biographical contextualising, and often comparison between works. The clearest line through his oeuvre is the gradual brightening of his colour palette and the reduction of the amount of paint he uses on a canvas. It is tempting to see this as an easing up, a move from penumbral to diurnal. But these shifts were born from necessity: dark colours were cheaper when Auerbach was young, and he had not yet worked out how to properly scrape the paint off a canvas.

Frank Auerbach. Reclining Head of Julia, 2019-20. Acrylic on board, 22 1/4 x 22 1/4 in (56.5 x 56.5 cm). © The Estate of Frank Auerbach. Courtesy Frankie Rossi Art Projects and Michael Werner Gallery.

In his later decades, Auerbach was less able to roam around London and began to focus almost solely on portraits. This is where his work starts to seem more sequential. There are a pair of reclined heads of his wife Julia from 2015 and 2019-20. The latter is featherlight, its lights spaced apart, as if she is gradually disappearing. In his final years, he turned to depicting himself, containing a process that had begun with his early charcoal heads. A 2023 work on paper sees his face emerge from lighting-sharp lines of India ink. The final painting, from the year of his death, brings us close to the lines of his bones. This is the man of a painter facing up to the present.