Helen Chadwick, Piss Flowers, 1991-2. Installation at Frieze, 2013. © Estate of Helen Chadwick. Courtesy of Richard Saltoun Gallery, London, Rome and New York. Photo: Peter White.

The Hepworth Wakefield

17 May – 27 October 2025

by ANNA McNAY

Ascending the stairs into the galleries at the Hepworth Wakefield, one is met by the sweet, cloying smell of melted chocolate; turning into the gallery, the culprit is revealed – a large fountain bubbling over with the brown confection: a real-life Willy Wonka’s chocolate factory. And yet, while my senses are activated and engaged at this level of childhood memory, this is not – despite the number of (appropriate) engagement activities suggested at child-height – an exhibition for pre-pubescents. It oozes raw sexuality at every turn, and the scent of sweaty bodies moving rapturously is conjured just as strongly as the chocolate – described by the artist as “a pool of primal matter, sexually indeterminate, in a perpetual state of flux”1 – and just as strongly again as the imagined smell that accompanies Carcass in the next gallery, a two-metre-tall glass tower filled with rotting vegetable remains (and, on my visit, topped rather beautifully with a bunch of magenta rhubarb. Did you know Yorkshire was host to an annual rhubarb festival? No, me neither – but I digress …). The artist behind this sensory onslaught is Helen Chadwick (1953-96), and this is her first major retrospective in more than two decades.

Helen Chadwick, Loop my Loop, 1991-2. Harris Museum, Preston. © Estate of Helen Chadwick. Photo courtesy of Richard Saltoun Gallery, London, Rome and New York.

Described by her friend, the historian Marina Warner, as “angry, edgy, witty, wicked,”2 Chadwick was born to a British father and a Greek mother. She grew up in Croydon. Perhaps unsurprisingly, with hindsight, biology and geography were her best subjects in school; perhaps surprisingly, however, she failed O-level art. She nevertheless dropped out of her plans to study archaeology to do a foundation course in Brighton – inspired by gallery visits with her mum – and, although art school reasserted her lack of interest in the more traditional skills of drawing and painting, she later remembered making “unusual congregations of forms – many based on her own body – in materials such as jelly, chocolate and liquorice”.3 Warner further embellishes Chadwick’s character, saying: “She was Helen of Troy, Puck, Joan of Arc, Venus – Luciferian, angelic, spirited, ardent, eloquent, and a generous celebrant of all things erotic, while approaching them with sharpened intellectual tools.”4 Certainly, this exhibition engages the visitor as intellectually as it does viscerally – the stimulation is both mental and other.

Helen Chadwick, Wreath to Pleasure, No. 6 (Chrysanthemums, Angel Delight). © Estate of Helen Chadwick. Photo courtesy Richard Saltoun Gallery, London, Rome and New York.

The walls around the chocolate fountain, Cacao (1996), display Wreaths to Pleasure (1992-93), which comprises 13 circular photographic works exploring sexual pleasure, deviance, materiality and excess. Initially, they might appear simply as flowers, but, look more closely, and the arrangements (of orchids, bluebells, buttercups, dandelions, narcissi, tulips, roses, daisies, honeysuckle, gerbera, etc), suspended in a mixture of pleasurable and/or toxic liquids (Windolene, Fairy Liquid, bubble bath, tomato juice, milk) are just that little bit suggestive of vaginas, penises, breasts, or often both. This merging of flowers, foodstuffs and sexuality is central to Chadwick’s work as a whole. She once said: “A broad conception of my activities over the years is an involvement with female sexuality. I have felt that a conflict exists between a conditioned and an instinctive response. I have attempted to find a language to express this ambiguity and the complex feelings that this area of involvement generates. The work would seem to represent a fusion between a world of pre-defined archetypes and subjective flow of experience.”5 Elsewhere, she added: “If I have an intent, it is to open up a crease in language and look at what cannot be articulated – the phenomena of consciousness, the enigma and riddles of selfhood, the moments of sexuality and emotionality.”6

Helen Chadwick with Piss Flowers from the exhibition Helen Chadwick: Effluvia, Serpentine Gallery, 1994. Photo: © Kippa Matthews.

This is certainly clear in Piss Flowers (1991-92), which was made together with her husband David Notarius, while on a residency at the Banff Centre for Arts in Alberta, Canada. Using an oversized cookie cutter (there’s Willy Wonka again – or maybe Alice in Wonderland?), they packed the freezing snow in tight and took it in turns to urinate over the shape, before casting the imprint. Who would have thought you could make an artwork out of micturition? Even Chadwick noted the incongruity of how the flowers were made and what they were. The outcome, however, is spectacular – a “penis-envy-farce … as implausible as the delicacy of an elephant”,7 whereby Chadwick’s concentrated flow of urine formed (once in its inverted cast) a phallic stamen-like protuberance and Notarius’s more spattered flow created the shallow petals. Chadwick describes the wonder of the outcome as stemming from the fact that they were “not things made, [rather] the product of things that happen, chance things, even if there was a kind of premeditated script or choreography for how they were made”.8 In an accompanying poem, she describes the flowers as “vaginal towers with male skirt”.9 One can’t help but wonder and smile at the simultaneous complexity and simplicity of this work. As the exhibition’s curator, Laura Smith, puts it: “[Chadwick’s] art was mischievously unruly and luxuriously disruptive,”10 or, in the words of the art critic Louisa Buck: “She could ricochet from the cerebral to the profane in half a sentence.”11

Fancy Dress and Sculptures Photograph Book, 1974. Leeds Museums and Galleries (Henry Moore Institute Archive of Sculptors’ Papers). © Estate of Helen Chadwick.

Challenging opposing binaries is another omnipresent aspect in Chadwick’s oeuvre. In the foreword to the catalogue, Warner writes: “She continued to puzzle over the opposition between beauty and nature, the ideal and the organic, the permanent and the transitory, the bodily and the aesthetic.”12 Indeed, this exhibition is both entrancing and abject, conceptual and visceral. Chadwick’s unwillingness to accept any binary hierarchisation of the world, though, from the conditions around male and female gender specificity to, especially, the separation of body and mind, allowed her to radically explore the mechanisms of the body – physically, emotionally, sensually, sexually and sensorially.13

Another of Chadwick’s seminal pieces recreated for the exhibition is Ego Geometria Sum (1983-84). In her copy of Susan Griffin’s book Woman and Nature (held in the Chadwick Library at the Henry Moore Institute), Chadwick has underlined the following lines: “The cause of the universe lies in mathematical harmony which exists in the mind of the creator,”14 which speaks nicely to the premise of this work, of which she wrote further in her notebooks: “Looking back to gain equilibrium by throwing the past off.”15 For this 12-part sculpture (the final piece is sadly missing as its Seattle-based collector didn’t want to lend it), Chadwick chose containers that had held her at different points in her life and “recreated” them out of plywood, mathematically precisely, with their size reflecting her mass at each age. For example, object number one represents the incubator that held her small, premature self as a baby. A later object is a play tent she shared with her brother, and a later one still is a piano. On their sides, she has directly exposed ghostly photographs of her adult self, using a special mixture of chemicals and a hairdryer to photosensitise the plywood. These containers are carefully placed on the gallery floor in a large spiral, set against muted baby-pink walls,16 which are hung with crushed sateen curtains and, in between, photographs of Chadwick with each construction. At the end, a vitrine holds The Juggler’s Table (1983), dolls’-house-sized paper and card maquettes for the larger work.

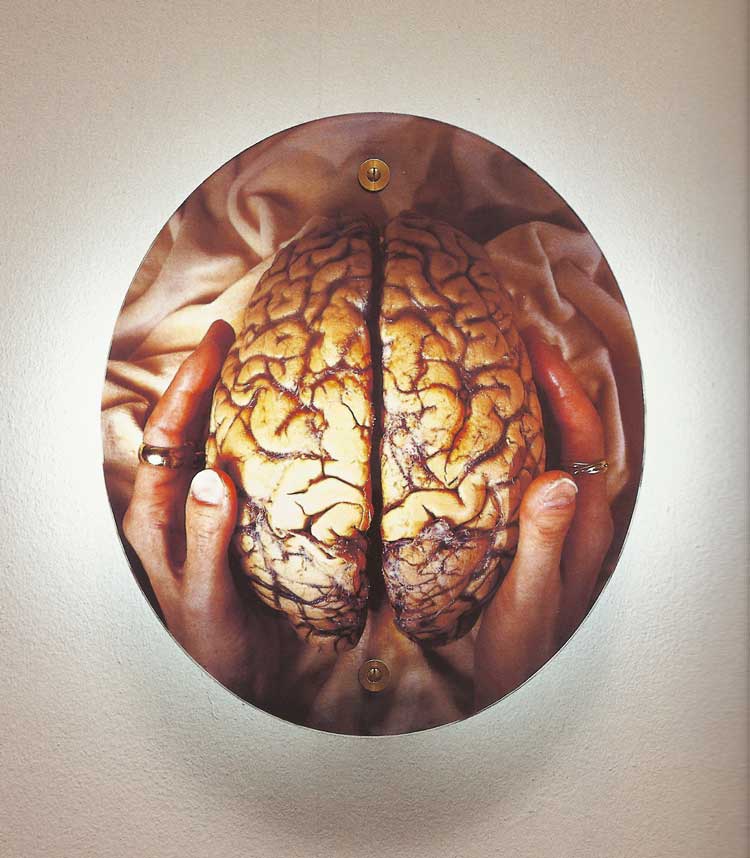

Helen Chadwick, Self Portrait, 1991. Jupiter Artland Foundation. © Estate of Helen Chadwick. Photo courtesy of Richard Saltoun Gallery, London, Rome

and New York.

Every detail of this curation has been meticulously thought out, which is nothing more than Chadwick, herself clearly a deep thinker, deserves. The hanging, on the next wall, of the seemingly out-of-place One Flesh (1985) – a subverted image of the Madonna and Child, in which one of the Virgin’s hands points to the baby’s genitals – it’s a girl – and the other holds scissors poised to cut the umbilical cord – follows, in fact, perfectly from Ego Geometria Sum, with its triangular iconic composition. (It also segues nicely into the contemporary exhibition running parallel to Chadwick’s: paintings of motherhood by the Scottish artist Caroline Walker – well worth the visit while there.)

In 1987, Chadwick became the only the second female artist to be nominated for the Turner Prize, for an exhibition held the previous year at the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA), London, called Of Mutability. This was where she first showed Carcass, intended as a monument to death, but which, Chadwick soon realised, was actually the epitome of life, as it bubbled and crackled away, its contents fermenting, until, one day … BOOM! … it exploded fetidly all over the gallery. “I want to catch the body at the moment when it’s about to turn,” Chadwick had said. “Before it starts to decay, to empty.”17 I don’t think even she envisaged capturing this moment quite so precisely. This time round, the piece has been built with a tap at the bottom to “bleed” the liquids each evening, four holes at the top to let the gases out, and it is made of 40ml Perspex instead of the 20ml of the original. Fingers crossed it – and the gallery – fare better this time. (No one has, as yet, as far as I am aware, volunteered to do as Chadwick did when Cacao got bunged up at the Serpentine Gallery in 1994: namely plunging their arm into the blood-temperature chocolate to scrape out the collected sediment.)

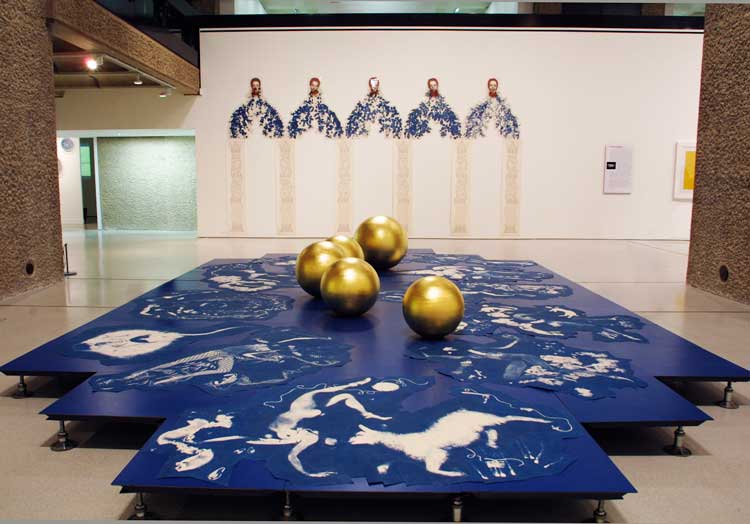

Helen Chadwick, The Oval Court, 1984-6. Victoria and Albert Museum, London. © Estate of Helen Chadwick; Victoria and Albert Museum, London. With generous support from the V&A.

Alongside Carcass, Of Mutability comprised a larger installation piece entitled The Oval Court (1984-86), which was intended as the corresponding monument to life, and described by Warner as “the largest self-portrait ever”.18 Basically, the work is a cornucopia of joy, desire, excess and love, which makes references to the sensuality of the rococo and to classical Greek style, as well as to Chadwick’s own Greek heritage. In her notebooks, Chadwick describes the oval basin at the centre of this work as a “fallen sky” or a “mystic womb”, and it is here that her own self achieves “one-ness with all living things”. In this basin, 12 figures swim, float and dance, each a collage of photocopies of Chadwick’s body. The figures embody the “12 gates to paradise”. Chadwick further describes them as “idealisations of the joy of love”.19 The xerox process is indexical, creating a direct imprint of the artist’s body, with the same intimacy as for Piss Flowers. The different collaged layers interact such that she is seen here holding a hare, embraced by another, there battling a swan (recollections of Leda) and there eating grapes. Elsewhere there are lambs and balls of wool and asparagus bundles tied by wool. Hands appear as if from nowhere, and there are fish in nets where Chadwick is wearing fishnets. The canny conception of the work was influenced by Leo Steinberg’s essay The Sexuality of Christ in Renaissance Art and in Modern Oblivion. Chadwick annotated her copy with the note: “Self as naked – immune to shame. Redemptive power of love, freed from Academic contagion of shame + male voyeurism + sexual possession.”20 Further, in her essay for the accompanying catalogue, the Swiss-born art historian Katrin Bucher Trantow suggests that, for Chadwick, The Oval Court implied “an architectural space and a place of courtship, where a revival of the Garden of Eden and a ‘new Eve’ would be unveiled, where female sexuality would be evident as a blessing rather than a disgrace”.21

Helen Chadwick, The Oval Court, 1984-6. Victoria and Albert Museum, London. © Estate of Helen Chadwick; Victoria and Albert Museum, London. With generous support from the V&A.

On top of the oval basin, there are five large golden spheres, which suggest the touch of King Midas, and, perpendicular against the wall, there are 12 columns, decorated with such plants as clematis, honeysuckle and grape, cut and shaped to hang like mistletoe – or, maybe, lungs – each of which is crowned with a weeping self-portrait of the artist. As they run down her face, her tears become lost in the foliage and fill the basin below. Here, Chadwick’s notes describe how the self seeks dissolution, “an oceanic feeling: expansion of awareness as in cathedral … craving to surrender identity to God, nature, art, love,” and how it finds this dissolution in tears: “self dissolves as salt in water – salt + water > tear.”22 Warner further cites Chadwick as saying: “Art, like crying, is an act of self-repair, to shed the natural tears that free us, make us strong.”23

Using her naked body was one of the most contentious and provocative things Chadwick could do, and this was to be the final time. Warner notes that feminist critics were as disturbed by the artist’s “embrace of luxurious beauty in the idiom of the 18th century” as they were by her “exultant” eroticism, which they felt demonstrated an uncritical and “suspect affinity with the ancient regime [sic], its inequalities, its sexual exploitation of women”.24 Nevertheless, by working with herself as her material, Chadwick mastered the greatest binary of them all, becoming both the subject and the object of her work.

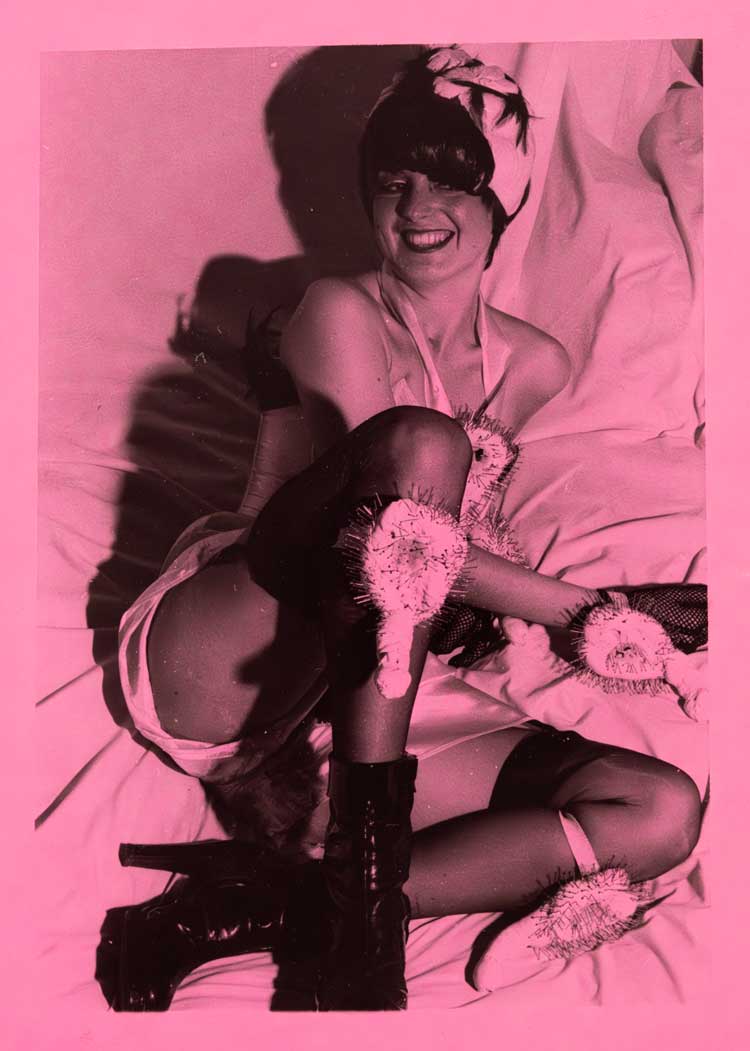

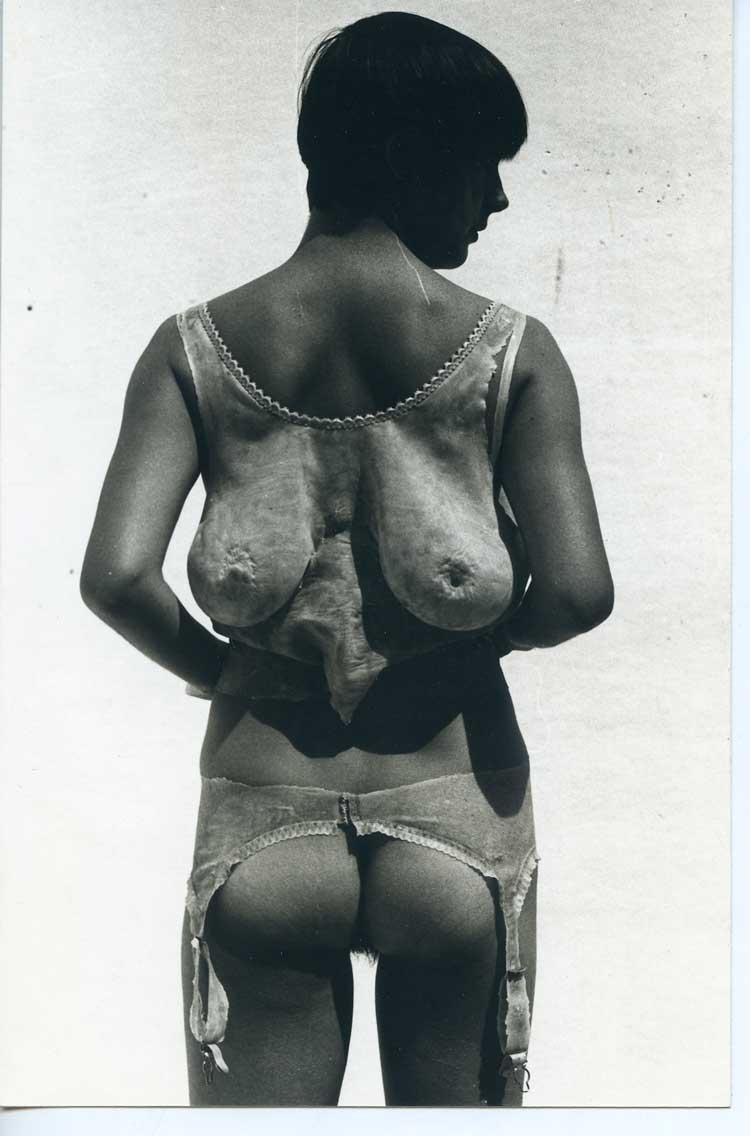

Latex costumes for Domestic Sanitation, 1976.

Leeds Museums and Galleries, Henry Moore Institute Archive of Sculptors’ Papers. © Estate of Helen Chadwick.

Alongside all these better-known, groundbreaking works, some of the smaller pieces, sketches and maquettes really shine and deserve mention. A room of early works features documentation of performance pieces from Chadwick’s BA and MA final shows. The half-hour piece, Domestic Sanitation (1976), for example, in which she and three friends are dressed in sealed latex costumes (painted directly on to the skin), doing housework and grooming one another, is described by Chadwick as “pre-Punk, erotic artefacts, quite glamorous, but with a disturbing edge … Fetishistic, quite exquisite, quite troubling”.25 It is documented here by photographs and a half-hour film, since the original costumes have perished with time. Some of her bed costumes from “act two” of the piece, however, survive, and four are on display, ranging from Rape Mattress Costume (1976), with the stuffing leaking out and a hole pierced where entry would have been forced, and Tart Duvet Costume (1976), with its flashing red nipples, suspender belts and multiple vibrators (rubber thimbles). Central vitrines include sketches and embroidery of strawberries and hearts, hearts entwined in penises, and a human torso fashioned out of sex organs of both genders. Alongside are cross-stitch templates for a set of knitted (used) tampons from across three days of an average woman’s cycle – the knitted work is on the opposite wall. As with the unveiling of the new Eve in The Oval Court, much of this work seems bound to “unshame” the things for which women most frequently feel shame.

There are, of course, plenty of Chadwick’s furry works and lightbox pieces, too. The curation offers a generous overview of her practice across her lifetime. Tragically, Chadwick died unexpectedly of a heart attack in 1996 at the age of 42. The obituaries were magnanimous, calling her “the most important artist of her generation”,26 and the last big exhibition of her work opened at the Barbican just six weeks later. In the light of this loss, the bodily imprints she left behind seem, like Carcass, all the more filled with life. Notarius once commented that Chadwick “taught a lot of people to think outside the box”.27 Even in death, it seems she cannot help herself.

• ARTIST ROOMS: Helen Chadwick is at Tate Modern until 8 June 2025.

References

1. Chadwick cited in Mortality, Desire, All Those Kinds of Words by Laura Smith, in Helen Chadwick: Life Pleasures, exhibition catalogue, The Hepworth Wakefield, 2025, page 123.

2. Foreword by Marina Warner, exh cat, 2025, page 7.

3. Smith, exh cat, 2025, page 21.

4. Warner, exh cat, 2025, page 8.

5. Chadwick cited in Notes on the Art of Helen Chadwick, Especially the Early Works by Niclas Östlind, in Helen Chadwick, exhibition catalogue, Liljevalchs Konsthall, Stockholm, 2005, page 9, cited in Smith, exh cat, 2025, page 13.

6. Objects, Signs, Commodities by Helen Chadwick, in Camera Austria International, issue 37 (summer 1991), page 9.

7. Chadwick cited in Golden Flowers by James Hall, in the Guardian, 25/01/94, cited in Smith, exh cat, 2025, page 112.

8. op cit.

9. Piss Posy by Helen Chadwick, exh cat, 2025, page 163.

10. Smith, exh cat, 2025, page 13.

11. Louisa Buck and Laura Smith in Conversation, exh cat, 2025, page 219.

12. Warner, exh cat, 2025, page 6.

13. Smith, exh cat, 2025, page 129.

14. Let the Monuments be Eroticised by Maria Christoforidou, exh cat, 2025, page 173.

15. Getting Inside the Artist’s Head by Eva Martischnig, in Helen Chadwick, exhibition catalogue, Barbican Art Gallery, London, 2004, page 48.

16. The paint for each gallery space has been specially created by Atelier Ellis, with the early-works space, for example, being a pastel chocolate brown.

17. Chadwick cited in What a Swell Party it Was by Andy Beckett, The Independent online, 01/06/96.

18. Quoted by Laura Smith at the press opening, 15/05/25.

19. Martischnig, exh cat, 2004, page 52.

20. op cit.

21. Bad Blooks and Fluid Taxonomies by Katrin Bucher Trantow, exh cat, 2025, page 2020.

22. Martischnig, exh cat, 2004, page 52.

23. Chadwick cited in Warner, exh cat, 2004, page 10.

24. Fetishistic, quite exquisite, quite troubling by Philomena Epps, exh cat, 2025, page 154.

25. Chadwick cited in op cit, page 141.

26. Cited in What a Swell Party it Was by Andy Beckett, The Independent online, 01/06/96.

27. Helen Chadwick: A Life in Six Artworks, Tate film online, 27/03/25.