Hufton+Crow_14.jpg)

Diller Scofidio + Renfro (DS+R), V&A East Storehouse. © Hufton+Crow.

by VERONICA SIMPSON

Diller Scofidio + Renfro (DS+R) made its name with an economical and inspired intervention of elevated greenery along a disused New York railway line (the High Line). After that, it rapidly became the starchitect of choice for eye-catching cultural centres – usually big, baggy, robust spaces – across the globe, some attracting controversy, such as The Shed at Hudson’s Yard, with its gimmicky sliding roof, which was criticised by the Art Newspaper (among others) for siphoning billions of funding into an arts building New York didn’t need while the city’s arts infrastructure itself is crumbling. Happily, the V&A’s new interactive and immersive archive, going under the banner of V&A East Storehouse, shows the architect in full command of that original triple-whammy of ingenuity, artistry and economy, delivering a building that is sweeter in the experience than it is on the eye. It is a retrofit to boot – a repurposing of a large chunk of the original 2012 Olympic broadcasting centre, where the world’s media gathered to enjoy London’s big Olympic moments.

Hufton+Crow_18.jpg)

Diller Scofidio + Renfro (DS+R), V&A East Storehouse. © Hufton+Crow.

There is nothing to enjoy about the 15-minute walk to get to it, however. From Stratford station, you trudge alongside a bleak dual carriageway through a soulless urban edgeland flanked by the capacious rear-ends of Stratford Westfield’s giant retail sheds, empty development plots filled with weeds and litter, and many of the now globally ubiquitous, bland and generic, high-rise blocks of flats. In the distance, you can see the new, five storey V&A East Museum, still under construction, scheduled for completion in 2026. It is a strangely lumpen thing (by Irish architects O’Donnell + Tuomey), wrapped in pleated concrete skirts, like a low-budget version of Herzog & de Meuron’s Tate Modern Blavatnik Building. So, I half expected some kind of architectural flourish or bauble to flag up the Storehouse, this new home for the V&A’s world-class collection, located opposite yet more charmless apartment blocks. But there is nothing to announce your arrival at a major cultural venue, bar the V&A logo stapled to the metal grilled facade.

Hufton+Crow_1.jpg)

Diller Scofidio + Renfro (DS+R), V&A East Storehouse. © Hufton+Crow.

Storage racks for paintings. Diller Scofidio + Renfro (DS+R), V&A East Storehouse. © Hufton+Crow.

It is DS+R’s vision for what is inside this 16,000 sq metre windowless shed that packs a punch – as well as the priceless contents - and won it the competition in 2018. You enter through a simple, welcoming lobby – no fanfare, just sliding glass doors on to pale plywood panels and shelving and Ikea-esque furniture, the layout of which signals an invitation to check out the adjacent cafe and leave your coats and bags in the cloakroom. And there in front of you is the glass wall behind which 250,000 objects, 1,000 archive items and 350,000 books are stacked, over four floors.

V&A East Storehouse. A recreation of the carved and gilded ceiling of the 15th century lost Torredo Palace of Toledo. Photo: Veronica Simpson.

The wow factor comes after you enter this climate-controlled section: after passing through double glass doors (like an airlock), you ascend a metal staircase and climb to the second-storey steel floorplate to find yourself in a vast central hall. Gantries and shelving as far as the eye can see are stacked right up to the huge artificial light 20 metres above (to protect the exhibits, there is no natural light). Through a transparent glass area in the floor, you can see the 17th-century Agra Colonnade, an extraordinary relic of Mughal architecture from the fort at Agra, in Uttar Pradesh, and further treasures. It is spectacular – the eye flitting from a reconstruction of the ornate carved and gilded ceiling from Toledo’s lost 15th-century Torrijos palace on one floor to a two-storey section of the 20th-century concrete exterior wall and windows that once fronted flats in the Robin Hood Gardens estate in nearby Poplar, complete with oral histories of former residents, transmitted using QR codes on captions on the third-storey walkway, which brings you up close to it. Or you can peer into an exact reconstruction of a Frankfurt kitchen designed by Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky: a precursor of the kind of fitted kitchen we now enjoy, it apparently transformed kitchen design for the 20th century. Throw in early version computers, ancient carved sphynxes and Balenciaga ballgowns – it’s all here.

V&A East Storehouse. Reconstruction of a Frankfurt kitchen designed by Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky. Photo: Veronica Simpson.

Liz Diller, founding partner of DS+R, says: “We won the competition for our idea of this inside-out organisation. It seemed so obvious, because it was a media building so the outside of it is solid … (that) the light should be in the middle. From here, you can feel into and around the place in an easy, organic way.” The arrival in that hall is the thing, though. “It is meant to be cinematic – unfolding slowly. You are burrowing through a tunnel, ascending a stair and entering through the floor, arriving in the centre.”

This organisation of space subverts the usual museum programme. Diller says: “It’s conceived in three concentric rings between public and private. The most public parts are in the centre. The middle ring is semi-private [for visitors to navigate at their own pace]. And the outer edge is the most private.” Around the perimeter are rooms for delicate objects that need to be kept in deep storage, free of dust, light and humidity, plus offices, research and conservation spaces.

The pick and mix aspect of the display – neatly organised by London architecture and design studio IDK into a Meccano-esque grid of shelves and palettes, similar to a distribution warehouse – was inspired by the architects’ first visit to the traditional storehouse for the V&A: a Victorian building in Kensington, west London, called Blythe House, which had long ceased to provide enough space for the museum’s accumulations, nor the desired conditions in which to store them. Here, all the objects are mixed up, according to their environmental needs, and semi-shrouded. This sense of mystery and curiosity – the witnessing of the back of house workings of a museum – pleased the architectural team and drove the concept of an equally free-range aspect to the Storehouse’s display, preserving that sense of being allowed into a back-of-house area, but also the serendipitous adjacencies. “The driving idea was that it would defy the logic of conventional taxonomies. The V&A collection is eclectic. We decided to ‘lean in’ to the delirium. Rather than following a curatorial voice, here you have the opportunity to have this mysterious stuff unfold around you, to follow your curiosity and your interest. We have given agency to the public,” says Diller.

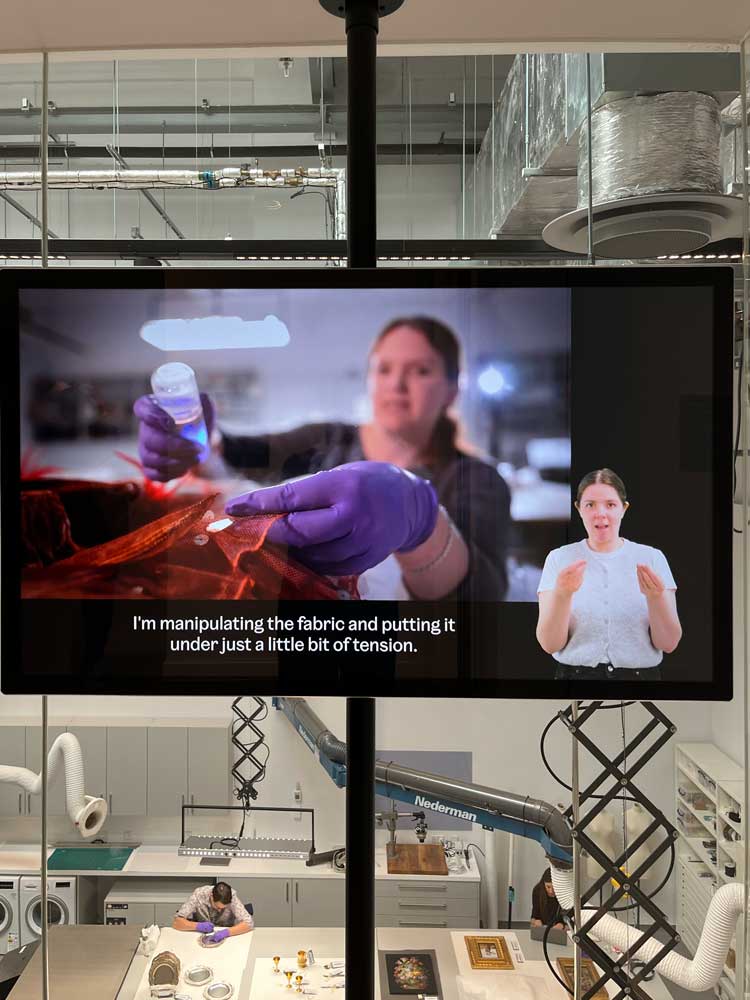

V&A East Storehouse. A film explains the work of the conservators visible in the laboratory the floor below. Photo: Veronica Simpson.

Anyone who wants to take a closer look at things that are not on open display is allowed to order five items from the collection and, with two weeks’ notice, come and spend quiet time with them for an “object encounter” in the study centre. And it is all free. Diller says: “It was an experiment. A hybrid. It’s not a museum, it’s something else. It’s a cabinet of curiosities.”

Hufton+Crow_5.jpg)

Diller Scofidio + Renfro (DS+R), V&A East Storehouse. © Hufton+Crow.

On each level there are “tributaries”– corridors that take you into and around this middle layer. There are grilles or windows at the periphery, beyond which are the secure storage spaces and conservation studios. Some of these are also visible. One can be viewed from the floor above, so as not to intrude on the staff in their white lab coats. There are double-height galleries where large scale items can be unfurled, such as the stunning, 10 metre-high travelling backdrop created by Alexander Shervashidze for a 1924 Ballets Russes production of Le Train Bleu. It’s a copy of Pablo Picasso’s small painting The Two Women Running Along the Beach (1922); and Picasso was so impressed by the accuracy and spirit of the copy that he signed it – making it the largest Picasso in the world. It has rarely been seen since its debut.

Along one of these tributaries is a display co-created with the museum’s east London community, showing a film of mainly local dancers from the East Asian diaspora, co-created with Akademi Dance, performing around the Agra Colonnade. There are also objects made with the V&A East’s Youth Collective.

The Storehouse’s location, on the eastern fringe of the city, allows the museum to tap into a new visitor group, says the V&A’s deputy director and chief operating officer, Tim Reeve: “The audience here are … one that an organisation like ours doesn’t tend to serve. There are one million people living in the four Olympic boroughs, who don’t visit the V&A. It gives us an opportunity to connect with and present our archives to an entirely new community.”

Reeve says the museum has worked intensively with the local community over the last eight years, including 100 local schools and colleges. He calls it “a genuine co-production … thousands of people who call east London home have welcomed us here and helped shape and design almost every aspect of the experience, to provide meaningful, democratised access”.

Attracting a younger audience is a major part of the Storehouse’s audience ambitions: “Living all around us there are 16- to 30-year-olds starting to form ideas about what they want to do with their lives.” Reeve hopes their presence here might encourage them to look into a creative career, adding: “We can say creativity is one of the very few success stories about the UK economy.” This is a deliberate swipe at the current government, which has done little to reverse the previous regime’s dismantling of creative education in state schools.

Hufton+Crow_9.jpg)

Diller Scofidio + Renfro (DS+R), V&A East Storehouse. © Hufton+Crow.

There are additional benefits to this open layout: it means curators as well as visitors can access items easily, but it is also designed so that the routes between objects in the middle layer can be changed, according to demand. After all, says Reeve: “We don’t know where visitors are going to spend time.

“It’s a big part of the programme to make transparent everything we do … There’s that physical immediacy between the collection and the people.” There’s also the way this open layout reveals the work of curators, technical and conservation staff. Reeve says: “It’s all about unpacking what we do as a museum. The tech team are magicians - the people who pack the objects, secure them so they can move around, install these architectural fragments - who would know those people exist?” For their part, the V&A’s back of house team have “embraced” this new presentation. “We have the opportunity to show off what we do to the public.”

Diller says: “It’s a working building: that’s one of the reasons why there’s no portico outside, no big announcement.” Reeve calls it “quietly heroic. People who are curious about museums and like museums will want to come here and look at that Balenciaga taffeta dress from the 1950s [currently the most requested item for the object encounters]. It’s everything here and so much more.”

V&A East Storehouse. The Study Centre where visitors can pre-order five items from the collection for close inspection. Photo: Veronica Simpson.

Visitor capacity is 1,000 a day – a drop in the ocean compared to the flagship V&A in South Kensington, which processes 100,000 visits in its busiest week, according to Reeve. But then South Kensington, points out Reeve, “is 80,000 sq metres. This is 16,000 sq metres.” There are 100 people working here, on front and back of house, with no obvious security staff – just security-trained people offering a friendly welcome at the door.

This is not the first visitable museum archive on this scale – Rotterdam’s Boijmans van Beuningen got there first, with its giant glitterball building designed by MVRDV. Diller acknowledges: “Boijmans got a head start. But it was a ground-up building, whereas we were adaptive re-use. There’s something very different in the ethos of this one. Where Boijmans does have a prophylactic layer between public and artefacts [artefacts are separated from the public by glass walls] we have none.”

“If it proves that it works,” says Diller, it could be a model for future museums. Was this the building the client needed still – from a competition won in 2018? It feels like a different age, we agree, “but it feels like we would have done it the same way we did today,” she concludes.

“It is one of the big issues of contemporary architecture, the speed of change of everything out there is so fast – including political upheavals and the economy and social structures and technology and the environment; everything is changing so fast. Architecture is really slow. Yes, there are buildings that feel like dinosaurs when they open. I think this building has always been light on its feet - the interpretation, the way the collection is displayed, it was kind of relevant when we imagined it, it continued to bring everyone along on this journey, the curators, the leadership. For it to be effectively the same building as the one we conceived when we started this, it means there was something right.

The conservators at work viewed from the viewing platform above. Photo: Veronica Simpson.

“How do you build for a future that you don’t know, that you can’t predict? And how do you do that without being generic, because you could do that. Buildings like this, which are just a frame structure, very simple, they can be anything you want them to be. New buildings need an identity. But then you’re weighing these issues of, how do you make a contemporary classic that doesn’t just become irrelevant and obsolete tomorrow? It’s a complicated thing.”

I suggest to Diller that three constraints helped to lay out the conditions for this innovative, exciting new kind of museum: one, the V&A had to move its collection somewhere anyway – it’s a building born of necessity, not vanity. Two, it was adaptive re-use so there was no need or opportunity to make it a statement building. Three, the V&A already has such a strong identity that it’s possible to sit back and let the contents be the star.

Diller says: “Had we done this from the ground up, I have no idea what it would look like. The Boijmans is a shiny object that is wanting to be an attention-grabber. With all due respect to MVRDV, it was a very different kind of project. This was a practical project. Design had a role here, and imagination had a role here, it wasn’t strictly a pragmatic project. And the budget was pretty restricted. In many ways, we dealt with the inheritance of what we got and worked with it. And it worked out well, because I think the balance is struck nicely here because it’s quite quiet but also dramatic.”

And let’s not overlook the extraordinary amount of time it took to simply quantify and assign every object in the collection. Diller jokes: “It took the same amount of time to design it as it took to move the collection into the building. Everything had to be picked, unpacked, scanned, measured, the whole process of identifying everything and thinking about where it would go was enormous. And the result looks just like the rendering.”

Whether the allure is enough to help transform this edge of city site into a new cultural quarter, as was intended, post Olympics, I have yet to be convinced. There is now a Sadler’s Wells outpost, an eastern arm of the central London dance venue. I’m still unclear as to why we need the second museum, V&A East. There will soon be a David Bowie Centre – the V&A’s presentation of Bowie’s collection will complete later in 2025. But certainly the Storehouse – the whole experience, as well as its remarkable contents – made me vow to return, and on a regular basis.