How Painting Happens (and why it matters) by Martin Gayford, published by Thames & Hudson. © Thames & Hudson

reviewed by DAVID TRIGG

“Every successful painting creates a new world, which we can inhabit for as long as we care to look at it,” writes Martin Gayford in How Painting Happens (and why it matters). But how do painters set about making a painting? That is the question at the heart of this compelling book, which explores the inner workings of the painter’s craft, examining how paintings are born, how they come together, and how this ancient but still relevant activity is a finely balanced interaction between mind, hand and physical matter.

Across 28 concise and lavishly illustrated chapters, the British critic explores what Oscar Murillo describes as the “infinite well” of painting – a mysterious, inexhaustible source that “always gives”. But Gayford has his own deep well from which to draw: decades of looking at, thinking about, and writing on painting; not to mention half a lifetime spent speaking directly with painters in their studios. It is this intimate and far-reaching knowledge of his subject that makes Gayford’s book so engrossing: a goldmine of quotes, anecdotes and insights.

Oscar Murillo in front of his painting manifestation, 2020-22. Oil, oil stick, graphite, and spray paint on canvas and linen, 349.9 × 480.1 cm (137 ¼ × 189 in). Photo: Jason Schmidt © Oscar Murillo. Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner.

“Painting is a difficult,” Gayford acknowledges, especially the creation of something that is truly original. “Finding new areas to explore can be a formidable challenge,” he writes, and yet, page after page, we find examples of artists who have done just that, many in defiance of Paul Delaroche, who, in 1839, declared painting to be dead after he had witnessed Louis Daguerre’s invention of the daguerreotype. It was, writes, Gayford, “a diagnosis that was far from accurate and followed by one of the most glorious eras in the entire history of the art – the epoch of Monet, Manet, Van Gogh and Cézanne”.

Gillian Ayres, Cwm, 1959. Oil and ripolin on board, 160 × 305 cm (63 × 120 ¹⁄₁₆ in). © The Estate of Gillian Ayres, Courtesy of Marlborough London.

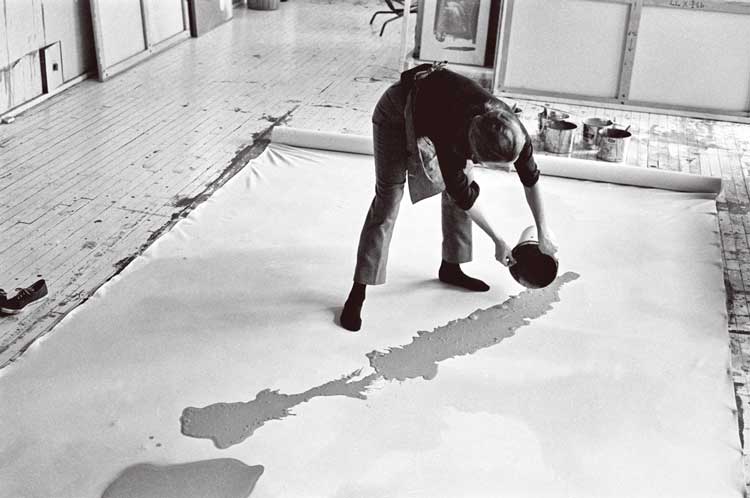

The first chapter deals with how painters overcome the problem of the blank canvas. We hear from Van Gogh, Gillian Ayres, Helen Frankenthaler, Lee Ufan and others, who all found their own unique way of getting started. For some, it begins with drawing, while others let the paint dictate the process, through brushing or pouring; some, such as Rebecca Horn, have even used painting machines. What they all have in common is that they dared to make a mark. As Van Gogh wrote to his brother Theo: “Many painters are afraid of the blank canvas, but the blank canvas IS AFRAID of the truly passionate painter who dares.”

Helen Frankenthaler at work on a large canvas, 1969. Photo: Ernest Haas. © Helen Frankenthaler Foundation.

Of course, once started, it is imperative not to give up: “Willingness and capacity to carry on is crucial for a painter,” notes Gayford. But then comes the problem of knowing when you are done. For Euan Uglow, who didn’t like the notion of finishing, his paintings simply “stopped”, brought to a point where they could progress no further. A whole chapter is dedicated to this topic, with the discussion including several artists who embraced the idea of leaving their work “unfinished”, from Patrick Caulfield to Michelangelo, and even Rembrandt. “This implies a radical idea,” Gayford suggests: “Perhaps an unfinished work is actually better, nobler, more philosophically sophisticated than a neatly done and dusted one.”

Patrick Caulfield, Unfinished Painting, 1978. Acrylic on canvas, 76.2 × 91.4 cm (30 × 36 in). © The Estate of Patrick Caulfield.

A significant theme of the book is that the act of painting is essentially a material exercise, one that involves the physical manipulation of a medium, yet at the same time one that is not divorced from thought or feeling. “Painting is a physical and an intellectual activity,” Gayford writes, and many pages are dedicated to exploring how great paintings are a marriage of the two.

In several chapters, the physical nature of paint itself comes under scrutiny, and Gayford joins with Howard Hodgkin in marvelling at how brushes loaded with pigment can produce convincing images of the real world. It is an aspect of painting that, in Hodgkins’ words, “is not easy to analyse, because it is a type of magic”. This is explored most viscerally in a chapter titled Flesh and Meat, which looks at how paint has been used to replicate the qualities of flesh, from the works of Rembrandt and Chaïm Soutine to Francis Bacon and Zeng Fanzhi. As Willem de Kooning once remarked: “Flesh is the reason oil painting was invented.”

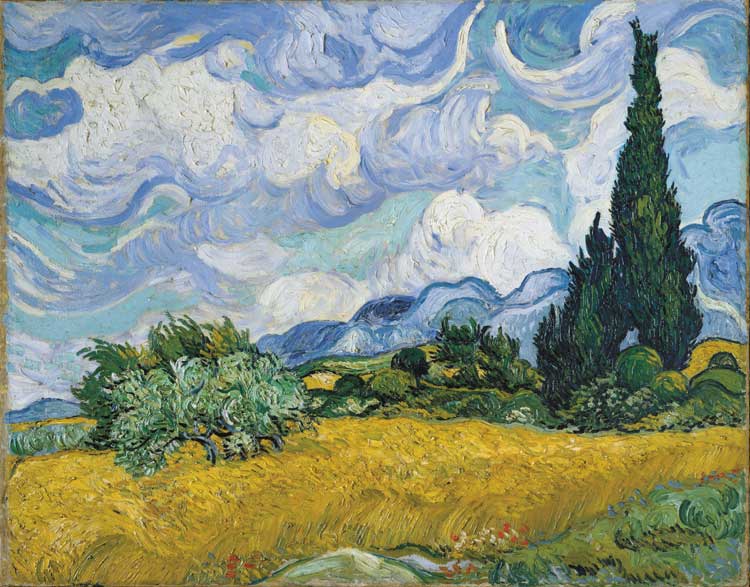

Vincent van Gogh, Wheat Field with Cypresses, 1889. Oil on canvas, 73.2 × 93.4 cm (28 ⅞ × 36 ¾ in). Metropolitan Museum, New York. Purchase, The Annenberg Foundation Gift, 1993.

Elsewhere, Gayford examines the materials on to which pictures are painted: “What is underneath a painting is still part of a picture and will affect it in various ways,” he notes in a fascinating chapter on the myriad supports that artists have employed. Here, we learn why Van Gogh painted on to tea towels, why Bacon always glazed his paintings, and how a commercially produced board game became integral to the work of Jackson Pollock. In delving into the nitty gritty of how paintings are physically constructed, Gayford explains why Patrick Heron had to work non-stop for 14 hours in order to paint the ground of his enormous canvas Long Cadmium, with Ceruleum in Violet (Boycott) (1977).

,1977.jpg)

Patrick Heron, Long Cadmium, with Ceruleum in Violet (Boycott), 1977. Oil on canvas, 198.1 × 396.2 cm (78 × 156 in). © The Estate of Patrick Heron.

Heron is celebrated for his abstract paintings, though how useful, really, is the term “abstract”? “One unsolved conundrum is whether there is any mark, blot, line, or form that does not correspond to something in the visible universe,” Gayford ponders, noting that it is human nature to try to find meaning in whatever one is looking at.

Painters do not work in a vacuum and are always learning from one another, whether through peer exchange or dialogue down the centuries. Picasso was obsessed with El Greco, ever since he saw the artist’s paintings at the Prado in Madrid in 1897, and Gayford draws out the fascinating visual links between the two artists before showing how painters such as Jean-Michel Basquiat and Claudette Johnson have in turn been influenced by the modern Spanish master’s works. We are shown numerous examples of “the random but momentous connections that can exist between pictures”, and how “visual DNA is exchanged over a gulf of centuries”. We also learn what Giotto’s cycle of frescoes from the first decade of the 1300s have in common with the sculptures of Anthony Caro (a rare moment in the book in which we hear from a sculptor).

In a way, all painting is “sculptural”, in the sense that it involves the moving around of a three-dimensional substance on a physical support. This is underscored by the thick impasto brushstrokes of Van Gogh’s Wheat Field with Cypresses (1889), which are reproduced in closeup detail, revealing the picture’s slathered surface. “It is partly this sculptural aspect of painting that makes it, strictly speaking, unreproducible,” notes Gayford, remembering that Jenny Saville once made the point that painting’s power is only truly found when you physically show up in front of it.

Gayford’s eloquent prose, his rich and vivid descriptions, and infectious enthusiasm for painting stir up a hunger for more. And while the book’s copious, full-colour illustrations are a visual delight, they cannot compare with seeing the real thing. This is a volume that, once you have finished reading how painting happens, makes you want to leave the house, visit a gallery, and experience for yourself why it matters.