Ruth Asawa: Retrospective, installation view, SFMOMA; artwork: © 2025 Ruth Asawa Lanier, Inc., courtesy David Zwirner; backdrop photograph: © 2025 Rondal Partridge Archives; Photo: Henrik Kam.

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art / Legion of Honor, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco / Walt Disney Family Museum

by JILL SPALDING

Ruth Asawa: Retrospective, at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMoMA) until 2 September, is the storied artist’s first posthumous career exhibit, and it’s a stunner. The curatorial challenge of whittling down Asawa’s extensive output – she worked ceaselessly until her death at 87 – was met with 300-plus superb examples of the suspended, looped-wire sculptures that have placed her in art’s pantheon and the works on paper that informed them. Block out serious time for your visit because it won’t be a walk through. Should this be your first encounter with Asawa’s signature rhythmic, looped-wire sculptures, your first reaction will be amazement. Even the smallest is as convoluted as mesquite, and even the largest, although weighted with metal, when suspended turns to fairy dust.

Most striking is the fall-off of “isms”. Work that in Asawa’s male-dominated and modernist era was seen as feminine and specific now feels generic and timeless, and the humble materials that had once labelled the hand-weavings as craft now read as high art.

,-1973.jpg)

Ruth Asawa teaching a Baker's Clay workshop at the San Francisco Museum of Art (now SFMOMA), 1973. Photo courtesy Ruth Asawa Lanier, Inc

Although defined by her mastery of brass, copper and galvanised wire, even the simplest material would serve – both as inspiration and teaching tool – for what Asawa termed radical creativity. Glimpse the endearing teaching moments filmed in her classroom as she introduced her young students to the possibilities of clay, crayons, paints and twigs that she herself often used. More complex was the alchemy Asawa wrought from closely observed biomorphic forms – melons, shells, eggs – found in nature. What sounds elementary (“You make a line, a two-dimensional line, then you go into space, and you have a three-dimensional piece”) defies optics as woven interiors become the exterior. Think, too, given metal’s obduracy, of Asawa’s manual dexterity (deviating one-16th of an inch could throw a work off if not immediately caught and corrected) and of the physical injury that her scarred thumbs gave witness to.

Ruth Asawa. Untitled (Two Watermelons), 1960s. Ink on technical paper, 20 x 30in (50.8 x 76.2 cm). Glenstone Museum, Potomac, Maryland.

Less fully covered here is Asawa’s drawing practice, honed early at Black Mountain College under the tutelage of Josef Albers and Buckminster Fuller – perhaps because it was featured in the Whitney Museum’s 2023 Ruth Asawa Through Line exhibit – but she drew daily, calling it her “greatest pleasure and the most difficult”. Charming and dexterous, the few examples shown here, such as Untitled, Two Watermelons (1960s), show her to be proficient with pencil and watercolour. While the drawings stand on their own, they serve principally here to illustrate why the hung sculptures are her defining achievement – illusions formed of relentlessly looped wire into nesting, interlocking, seamless parabolas that morph clarity into mystery and weave space itself.

Ruth Asawa: Retrospective, installation view, SFMOMA; artwork: © 2025 Ruth Asawa Lanier, Inc., courtesy David Zwirner. Photo: Don Ross.

Airy and transparent, but also enigmatic. Pause before a large one and you will feel a dark undercurrent. The heavy woven metals are laden with meaning – an unspoken reference to the barbed wire used to enclose wide open lands into fiefdoms, confine roaming herds, and encircle the young Asawa and her family in a wartime prison camp. The lightness prevails. Extensive wall-captions and videos detail the process that enabled it, but so improbably woven are the suspensions and so subtle their impact that what you may have learned about her technique is suspended as well. On exiting, only the wonder remains.

A subtler takeaway, in this noisy moment of immersive, interactive, artificial intelligence-driven and increasingly branded installations, is of motion inverted. Asawa’s suspensions are static. The only movement is of their shadows, activated only by walking past and around them, or – as during my visit – by a visitor blowing on a small work as wispy as dandelion fluff. Recalling a time when art was thought healing, the quieting immersion in Asawan stillness and the silence of etched space induces the meditation of a Zen garden.

Ruth Asawa: Retrospective, installation view, SFMOMA; artwork: © 2025 Ruth Asawa Lanier, Inc., courtesy David Zwirner. Photo: Don Ross.

Take to the streets for Asawa’s legacy; her Aurora fountain on the Embarcadero, the Origami Fountains in Japantown, the Andrea mermaid fountain in Ghirardelli Square, and the renamed Ruth Asawa San Francisco School of the Arts. Speaking to her impact, Asawa’s wire sculptures were featured on a 2020 US postage stamp, exhibited at the 2022 Venice Biennale, and joined Gwyneth Paltrow’s collection as a lookalike by a different artist. Speaking to her lasting impact, SFMoMA received $1.5m to support this retrospective, the largest corporate grant in its history for a single exhibit.

Wayne Thiebaud, 1920-2021. You know his work. Pastel, undemanding, easy on the eye, and in the accepted sense, decorative. Fodder for posters. Look again. In Wayne Thiebaud: Art Comes from Art, at the Legion of Honor, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco until 17 August, you can plumb the depth, scholarship and dexterity of this most beloved of northern California’s home-grown artists. Comprised of 65 original paintings, 28 copies of various predecessors’ works, reproductions of many paintings that influenced him and several he had collected, it constitutes a definitive life retrospective. Only his drawings are absent – perhaps because they featured in 2020 at the Crocker Museum, which has shown Thiebaud’s work every decade.

Wayne Thiebaud. Makeup Girl, 1981-2012. Oil on canvas, 30 x 24 in (76.2 x 60.96 cm). Private Collection, Courtesy Acquavella Galleries. © 2025 Wayne Thiebaud Foundation / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY Courtesy of Acquavella Galleries, New York.

Accomplished frontal portraits such as Nude, Standing (1975-76) belie no formal instruction. Sly winks such as Clown Boots (2018-19) speak to Thiebaud’s training as a cartoonist, as do the closely observed household objects to his years in advertising, and the seemingly casual abstractions of perceived reality (Diagonal Ridge, 1968) to his fascination with “extreme dualities”.

The galleries preceding the parade of signature cakes and sundaes that aligned him (erroneously) with pop art pull you viscerally into bold landscapes and San Francisco cityscapes whose salient elements are at once invented and familiar.

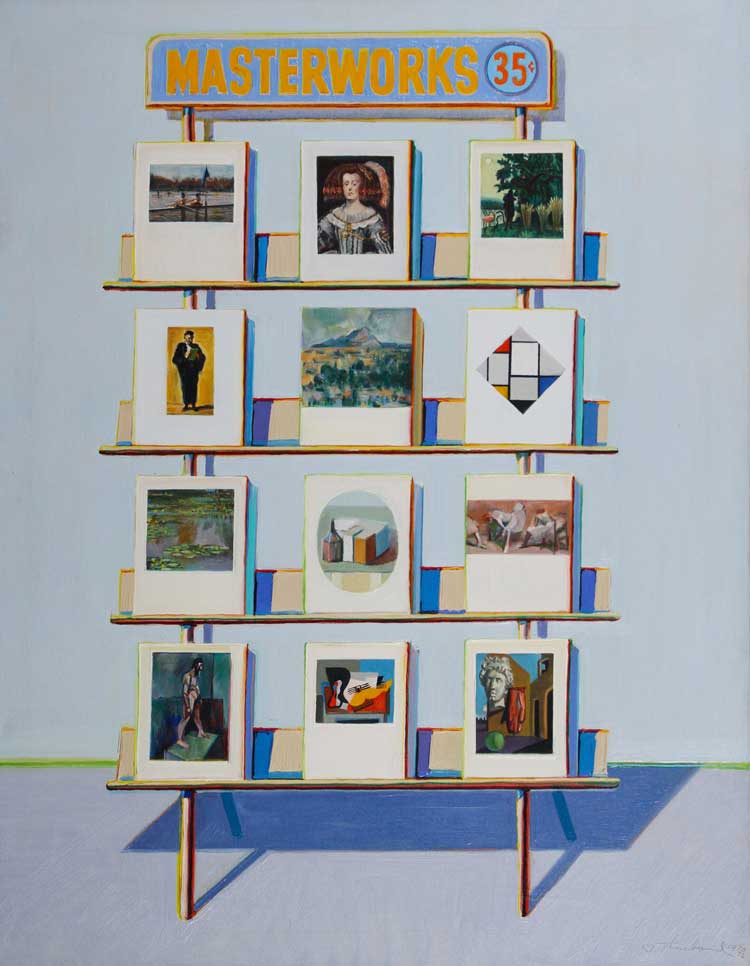

Wayne Thiebaud. 35 Cent Masterworks, 1970-72. Oil on canvas, 36 x 24 in (91.44 x 60.96 cm). Wayne Thiebaud Foundation © Wayne Thiebaud Foundation / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY.

Although Thiebaud vaunted his thievery from the greats – most explicitly with 35 Cent Masterworks (1970-72), a rack of diminutive works by such as Velázquez, Cézanne, Seurat and Picasso – much of the viewing pleasure derives from unforeseen jolts of recognition. Doesn’t that anchoring grid in Office and Shopping Mall (2005-21) riff on Mondrian? Surely, in Window Views (1989-93), the bird’s eye view through a window on to geometrically painted buildings and the shadows they cast across across an impossibly perpendicular city street is a homage to Diebenkorn! And, reaching back further, you won’t be the first to link Thiebaud’s serial cupcakes to Monet’s haystacks.

Wayne Thiebaud. Window Views, 1989-93. Oil on canvas, 72 x 64 in (182.88 x 162.56 cm). Private Collection © 2025 Wayne Thiebaud Foundation / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY Photograph by Randy Dodson, courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

Moving on to the parade of delicatessen foods, parse the familiar desserts closely. Link the alignment of Cakes (1963) to that of Edgar Degas’s hats. And see how the pillowy icing recalls the thick strokes of paint that built up Arcimboldo’s edible headgear. Conversely, how cleverly Thiebaud makes them modern. That flat slab of fish (Half Salmon, 1961) pares down to its essence Édouard Manet’s The Salmon, intentionally stripping away the Dutch still-life signage of curling lemon peel, side of asparagus and pewter platter that flagged burgher prosperity.

Learn, too, of Thiebaud’s erudite searches into such as the difference between positive and negative posited by Cézanne, and the compositional notions formed by Morris Louis from dyeing canvas with a “sort of watercolour, wet-on-wet technique” (Canyon Mountains, 2011-12). Spend time with the captions to learn of Thiebaud’s interest in “the substance of paint”, his struggles to juxtapose “various projective systems in a single work”, and his search for the personal voice he called “that fundamental thing”.

Wayne Thiebaud. Canyon Mountains, 2011-12. Oil on canvas, 66 1/8 x 54 1/8 in (167.96 x 137.48 cm). San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Purchase, by exchange, through fractional gifts of Gretchen and John Berggruen and Madeleine Haas Russell, and gift of the Thiebaud family © Wayne Thiebaud Foundation / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY Photograph: Katherine Du Tiel.

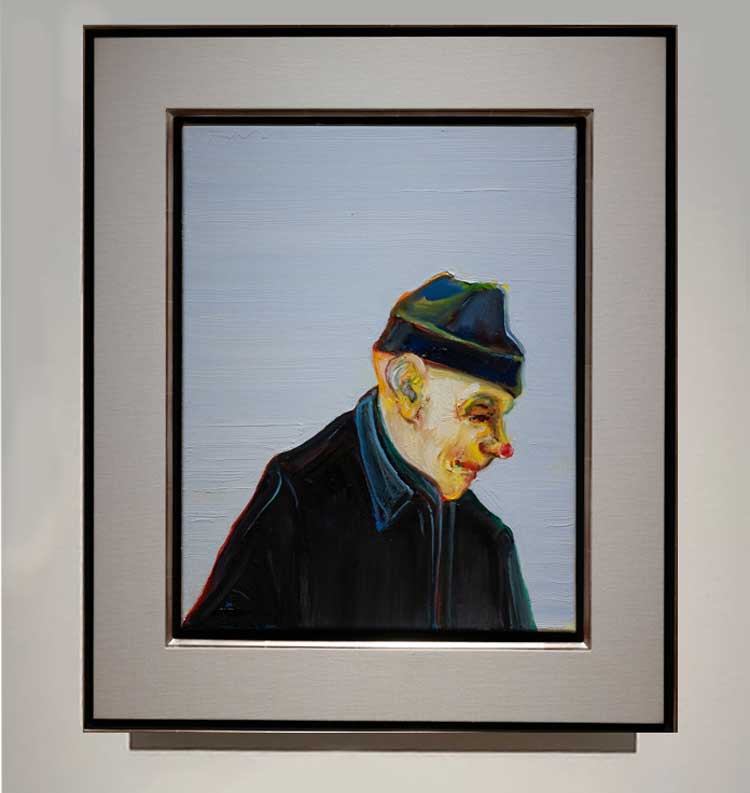

“Poignant” may not be a well-documented Thiebaud emotion, but his wrenchingly small self-portrait labelled One-Hundred-Year-Old Clown (2020), and painted at that age, weighted under the mountain he drew as his cap, his nose reddened by the devastating loss of his son and his wife, and rendered in profile to exit him from his life and – as positioned here – us from the exhibition, strikes the heart.

Wayne Thiebaud, One-Hundred-Year-Old Clown, 2020. Oil on canvas, 18 x 14 in. Installation view, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Jill Spalding.

Don’t leave, though, before viewing Violin and Shadow (1966), both for its nod to surrealism (those wildly distorted perspectives Thiebaud preferred to call magic) and for its segue to the little known jewel of the Walt Disney Family Museum, assembled by Walt’s daughter, Diane Disney Miller, mainly to showcase private holdings, which even with no changing exhibits draw streams of viewers.

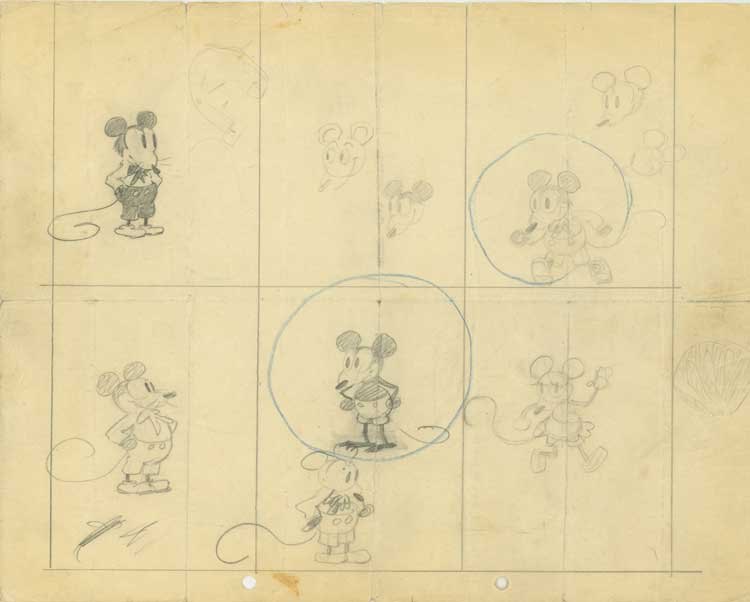

The earliest known drawings of Mickey Mouse, 1928. Courtesy Walt Disney Family Foundation, © Disney.

Discover here Walt Disney’s early vision – those breakout sketches and cartoons which would influence generations of artists from the studio that had constituted Thiebaud’s formative world: it was working there as a tracer that had instilled in him what he called the “aesthetic of caricature”.

Leading to the cartoons are cabinets of honours: medals, awards, citations and the “honorary” Oscar for Snow White and the Seven Dwarves – inexplicably, no Best Picture Oscar was accorded his famed feature films. Most intriguing is the antique map of France, included to reveal Walt’s lineal name to be D’Isgny (from Isigny-sur-Mer), flagging French ancestry.

Walt Disney’s Honorary Academy Award for Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, from the Academy Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences. Photo: Jim Smith, courtesy The Walt Disney Family Museum.

Shoring up the charm and eccentricity of the early animations was their laugh-out-loud humour, derived from the Bergsonian gambit of characters besting each other, plotting mayhem or sprinting to nowhere.

In the same way that the media empire of Disney World is Walt’s lifetime Oscar, this intimate museum is his biography. The hugely profitable themed parks are his triumphs, but here are his stumbles and bankrupting struggles. Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck were not born of whole cloth but of these embryonic sketches. Cinderella, Pinocchio, Bambi and Fantasia were not shot on lavish sets but compiled with thousands of labour-intensive and time-sensitive gels – all of an impermanence that only such a loving effort could preserve. Learn here, too, of the growing company’s great technological leaps forward – the first sound, live-action movies, and CinemaScope. Pioneering marvels, they stoked profits but never displaced the Walt Disney draughtsmanship and visuals that worked magic from Mary Poppins and Tinker Bell and went on to influence the aesthetic of such as Takashi Murakami, Kenny Scharf, Jeff Koons and Kaws.

Gallery 9: Disneyland and Beyond. Photo: Jim Smith, courtesy The Walt Disney Family Museum.