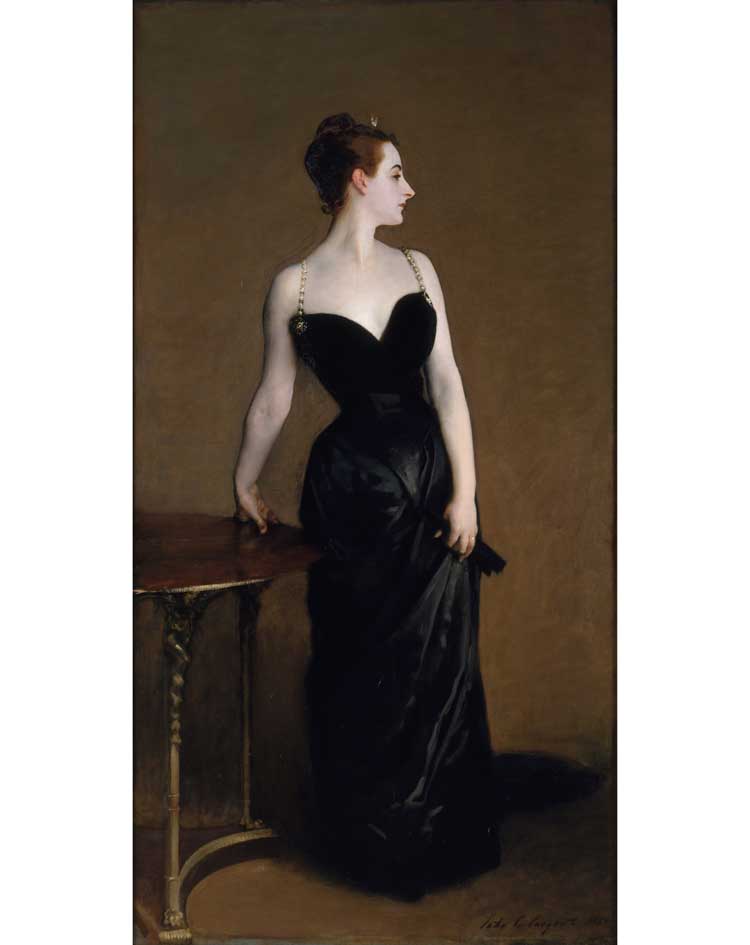

John Singer Sargent, Madame X (Madame Pierre Gautreau), 1883–84 (detail). Oil on canvas, 82 1/8 x 43 1/4in (208.6 x 109.9cm). Arthur Hoppock Hearn Fund, 1916. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

27 April – 3 August 2025

by MICHAEL PATRICK HEARN

As is apparent from the steady stream of young and old visitors gathering in long lines to get in to see Sargent and Paris at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, John Singer Sargent (1856-1925) is always a great crowd pleaser. Who can go wrong with even the slightest retrospective of the famous expatriate’s work? Sargent and Paris beautifully traces the painter’s youthful struggle to find his own personal style among so many contemporary French masters. This exhibition is a collaboration between the Met and the Musée d’Orsay in Paris as a tantalising celebration of the centenary of the artist’s death. It provides room for the curators to explore in greater depth certain aspects of the early work that are so often overlooked. The Met’s Stephanie L Herdrich and Caroline Corbeau-Parsons and Paul Perrin from the Musée d’Orsay also set out to debunk some of the absurd myths surrounding these works that have accumulated over the last 100 years. Sargent and Paris may feel like the fragment of a career, but it dazzles nonetheless. It will move to the Musée d’Orsay in September, where it will remain until early 2026.

The US has long embraced Sargent as its own, but was he really an American? Henry James, the painter’s friend, asked the same thing in Harper’s Monthly in October 1887. “We shall be well advised to claim him,” the novelist answered his own question, “and the reason of this is simply that we have an excellent opportunity.” (James was also under the delusion that there was more “American art” in Paris than in the US!) In his day, Sargent seemed American to the French, French to the British, and British to the Americans. He was one and all of them. Despite living almost his entire life abroad, he always considered himself an American. He was born in 1856 in Florence to American parents and travelled around Europe with his family before settling in Paris in 1874. His family were nomads. They moved so that their budding protege could partake of all the advantages the French capital offered aspiring artists. He was then just 18. He did not visit the US for the first time until two years later. He was fluent in English, French, Italian and German. By the time he left for London in 1886, Sargent was one of the most successful portrait painters of La Belle Époque.

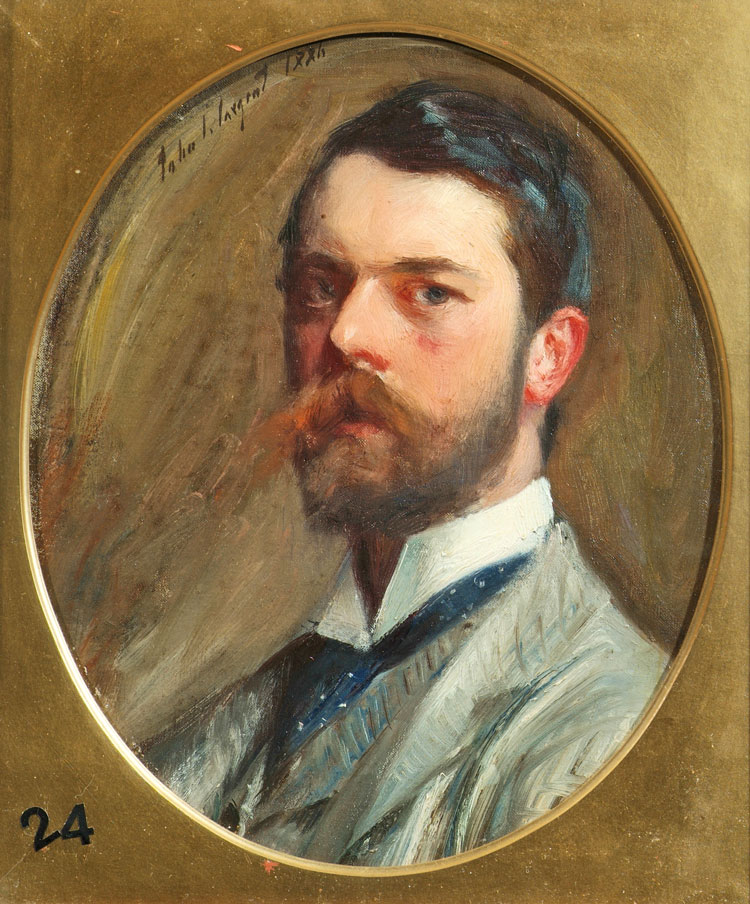

John Singer Sargent, Self-Portrait, 1886. Oil on canvas, 13 9/16 × 11 11/16 in (34.5 × 29.7 cm). Aberdeen City Council (Aberdeen Archives, Gallery & Museums collections).

The Sargents remained in Europe on an endless Grand Tour, primarily for his mother’s health after she convinced his father to abandon his medical career in Philadelphia to join her. Their son was largely homeschooled in the great art museums of Europe after more formal education proved futile. Although his father hoped the boy might pursue a naval career, his parents greatly encouraged his obvious and abundant natural artistic ability. From the age of 10, he vowed he would be a painter. His mother, an amateur in her own right, expected her son to produce at least one drawing a day. “He sketches quite nicely,” she admitted, “and has a remarkably quick and correct eye.” In Paris, “the irresistible city”, as James called it, he entered the atelier of the French realist Carolus-Duran (Charles-Émile-Auguste Durand) and also studied rigorously at the École des Beaux-Arts. He learned to master form and texture with just a few dexterous brushstrokes. Carolus-Duran taught his students to apply a heavily loaded brush wet on wet in what was known as alla prima (“at first attempt”) or direct painting, a loose, fluent, easy way of applying colour directly on the canvas that the old Dutch master Frans Hals had perfected in the Netherlands in the 17th century. Form was more important than outline. Gesture determined style. Consequently, there was little under-drawing in Sargent’s paintings. The results remain as spontaneous and fresh as when they were first painted. His 1879 portrait of his teacher is recognised as among his early triumphs. It proved to be a tribute and a challenge to this mentor’s status.

The earliest examples of his art from his student days are tight, meticulous and totally academic, often taken from the life model or static casts. It is fully acceptable without being particularly inspiring. He began to loosen up as he turned to portraiture and painting en plein air. He could produce a picture in just one sitting. No one else handled the brush or pencil with such agility and versatility as did Sargent. He was a bit of a show-off, the smartest kid in the room who always raised his hand first to give the right answer. Some people resented his sheer virtuosity. How could anyone paint so well all the time? One always senses the urgency of envy in the Parisian coverage of his work. The French newspaper L’Illustration took a rather low jab at “inconsiderate” Americans as early as 1881, by saying: “They have painters, like Mr Sargent, who take away our medals, and pretty women who eclipse ours.” He drew with his brush as adroitly as with his pencil, applying raw colours unmixed directly on to the canvas as did the French impressionists. Although he sometimes made voluminous preliminary drawings before tackling a composition, he rarely put pencil or charcoal to canvas. Look at the hands: he could fully render them with just a few deft strokes. They often bend and twist in disturbing contortions. He convincingly captured a likeness, particularly in his drawings, with a minimum of effort. He could turn even the most banal of subjects, such as the table in an outdoor cafe in Wineglasses (c1875), into a minor masterpiece of flickering afternoon light. Look how beautifully those drinking glasses are rendered in the foreground.

John Singer Sargent, In the Luxembourg Gardens, 1879. Oil on canvas, 25 7/8 × 36 3/8 in (65.7 × 92.4 cm). Philadelphia Museum of Art, John G. Johnson Collection, 1917.

Paris was then, of course, the centre of the art world. Sargent was just an insignificant sponge, soaking up all the exciting artistic influences swimming around him. Realism, naturalism, impressionism – it did not matter. He learned from all the current French schools of painting. James said that Sargent was considered from his first recognition at the prestigious but conservative Salon as “a recruit of high value to the camp of the Impressionists”. But Sargent never belonged to any specific school of painting. He was too versatile, too expansive in his tastes to be lassoed to any trend. He was still finding his way toward his unique, distinctive manner of expression in 1879 when he exhibited En Route pour la Pêche (Setting Out to Fish) (1878), a rigorously painted fishing scene, and In the Luxembourg Gardens (1879), a gentle easy-going summer interlude somewhat reminiscent in style and composition of the work of his American contemporary and rival William Merritt Chase. He often applied oil paint in layers as thinly as in his watercolours. The small, subdued seascape Atlantic Sunset (c1876-78) might have been painted by Claude Monet or James McNeill Whistler. Rehearsal of the Pasdeloup Orchestra at the Cirque d’Hiver (c1879) is a clumsy, gloomy imitation of Edgar Degas. Sargent went on excursions in the country with other artists as is apparent in the thoroughly charming Claude Monet Painting by the Edge of a Wood (1885), a souvenir of a visit to Giverny expertly rendered by Sargent in the famous impressionist master’s manner. Equally fine is An Out-of-Doors Study (Paul Helleu Sketching with His Wife) (1889).

_1889.jpg)

John Singer Sargent, An Out-of-Doors Study (Paul Helleu Sketching with His Wife), 1889. Oil on canvas, 25 15/16 × 31 3/4 in (65.9 × 80.7 cm). Brooklyn Museum of Art, Museum Collection Fund.

Ramón Subercaseaux in a Gondola (1880) suggests Manet, and Venice par Temps Gris (1882) suggests Monet again. The turbulent, formless Atlantic Storm (1876) in its rugged technique invokes Winslow Homer as well as, in part, Monet and Manet. One of the most radical and captivating of his Parisian pictures is the little A Gust of Wind (Judith Gautier) (1883-85), in which the lovely lithe girl is trying to hold on to her hat against the blast sending her skirts swirling about her tender form. It is fully achieved with the barest attempt of easy fluent brushwork and yet it is full of light and colour with a bright red mouth like a wound. All that he learned from Manet, Whistler and Pierre-Auguste Renoir is summarised in the elegant Madame Ramón Subercaseaux (Amalia Errázuriz y Urmeneta) (1880). Dramatic dashes of crimson flowers save it from being merely a symphony in black and white.

The title of this exhibition is a bit of a misnomer. Sargent took many side trips elsewhere in Europe and North Africa in search of “curious” scenes of local colour rather than obvious cliched tourist traps. While in Spain in 1879, at Carolus-Duran’s insistence, he encountered paintings by Diego Velázquez and Francisco Goya who profoundly influenced his work. He also copied the distinctive vigorous brushwork of Frans Hals. According to James, Velázquez “became the god of his idolatry” and “patron saint”. James suggested that, on more than one occasion, Sargent asked himself what Velázquez would have done. The appropriately named El Jaleo (1882), which translates as The Ruckus, came out of sketches made during a five-month trip through Spain and North Africa in 1879. This audacious explosion of light and shadow and colour and movement broke every convention of contemporary genre painting. One can almost hear the infectious cacophony of singing and stomping and snapping of fingers. The flamenco dancer commands the foreground in her slashing white skirt as Sargent dramatically rendered every detail of her dark whirling fringed shawl. He skilfully transported all the vibrant energy of Andalucían dance to his studio in Paris in 1882. El Jaleo was the talk of the French Salon that year, earning praise and ridicule as was the Parisian habit of the day. James dismissed the picture as ugly, “a perversion of life” that expressed “the latent dangers of the Impressionist practice”. Sadly, El Jaleo did not leave the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston for the Met. It has been replaced by the less dramatic The Spanish Dance (c1879-82) from the Hispanic Society of America in New York.

Italy and Morocco, too, lured Sargent. Unlike his French contemporary Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, the American apparently never explored the Parisian demimonde with his brush. However, he captured an Italian prostitute down a dismal alley with her pimp or procurer in Venetian Street (1880-82); and the locale of all those beautiful young women sauntering about in A Venetian Interior (1880-82) was probably a bordello. He did not adhere to any fashionable colour theory. His predilection was towards neutral tones bordering on the monochromatic. A few bright dashes of colour could make all the difference to the vitality of a composition. Unlike many of the impressionists, Sargent dared to use black and white. The impressionists avoided those pigments because they did not think they existed in nature. Sargent saw no problem with them. He was besotted with white on top of white. Common whitewashed steps and walls of Staircase in Capri (1878) provide a symphony of sunlight and texture. He recognised the ready market for “exotic” orientalist subjects such as the distinctive plastered Islamic architecture of Alhambra, Patio de los Arrayanes (Court of the Myrtles) (1879), Moorish Buildings in Sunlight (1879-80) and Courtyard, Tétouan, Morocco (1879-80). They virtually throb with translucent colours in the blazing afternoon sun.

_1880.jpg)

John Singer Sargent, Fumée d’Ambre Gris (Smoke of Ambergris), 1880. Oil on canvas, 54 3/4 × 35 11/16 in (139.1 × 90.6 cm). Clark Art Institute, Acquired by Sterling and Francine Clark before 1955.

The 1880 Moroccan painting Fumée d’Ambre Gris (Smoke of Ambergris) is a masterpiece of this white on white. It is a ravishing work for a 25-year-old. A young woman envelopes her lovely head with her silky, milky robe to breathe in all the musky intoxicating fumes from the censer at her feet. Although nearly concealed except for her tan forearms, she reveals all her natural allure in the blistering sunshine. Sargent lends an air of sensuality through the loose, masterful brush. “In her muffled contemplation and her pearl-coloured robes, under her plastered arcade, which shines in the Eastern light, she is beautiful and memorable,” wrote James. The picture was for him “exquisite, a radiant effect of white upon white”. (So many of the paintings in Sargent and Paris were described by James in his Harper’s essay that it could have supplied the initial outline for the current Met exhibit.) He masters the various textures and hues enveloped within overall shimmering light with his seductive strokes. It is extraordinary how all the light soaks up the dark. Even the shadows are subtle variants of white. It would be in monochrome if not for the subdued touches of pale colour in the faded oriental rug and the tiled floor and the persimmon of her sleeves and painted lips and fingernails.

Among his other early successes at the Salon were his three portraits of the same family. Édouard Pailleron was a successful French poet and dramatist, but is now remembered almost solely for his portrait. He stands casually confident in amazing whiskers and with one hand on his hip like one of Agnolo Bronzino’s Italian princes but dressed aesthetically dishevelled like Rodolfo in Giacomo Puccini’s La Bohème. Comfortably conventional, the 1879 painting is fully competent, but Sargent did not break any new ground here. Next came the plain wife with the sad eyes, Marie Buloz Pailleron, in the most striking of the three pictures painted in their country home in Ronjoux. “Charming” was what James called it. It is also the freest in its execution. It must have been her fiery auburn hair and pale pinkish skin that most excited Sargent. And he fearlessly plastered it against that vast flat expanse of lawn. It does not look as if the picture was painted out of doors: the awkward pose of her frumpy body suggests she must have been seated in his studio, bathed in artificial light, when he quickly put down all the intricate black beads and black lace of her dress with the immodest white petticoats, the sparkling dangling earrings, and that white tulle scarf like smoke about her throat. He was far more concerned with capturing her elaborate clothes than coddling his model. In spite of all the skill that went into it, it is not an entirely sympathetic portrayal. The garden background was likely an afterthought to bring out the full drama of her hair. He cleverly reminds the viewer that she is now outdoors with that one dead clandestine yellow leaf caught in her petticoats. His loose assured slashing brush invokes Renoir as well as that French impressionist’s composition and colour scheme, especially that fierce red against the cool grass green.

The next year, Sargent painted their children, Édouard and Marie-Louise. They endured what seemed to be (at least to the little girl) more than 80 sittings before Sargent was satisfied. No wonder Édouard scowls so. While the boy casually turns to the side towards the painter, his younger sister stares forward rigid, tense, uncomfortable, terrified. Sargent chose her fancy outfit himself to show off again his mastery of painting white on white. Neither child seems to trust the artist. Neither smiles. The picture is actually two separate portraits unconvincingly forged together on one large canvas. While they occupy the same settee, the two children do not really fill the same picture space. They fail to connect. For the background, Sargent supplied a satin cloth of swirling shimmering red that evokes similar treatment by Thomas Gainsborough and Joshua Reynolds of billowing clouds or curtains in their 18th-century English portraits. It is a lazy gesture: the painter is just filling in the spaces. There really is nothing stylistically pulling the three pictures together. Nevertheless, as shown in two vintage photographs in the catalogue, the Paillerons hung the three portraits in the same ugly, dreary, cluttered public room of their Paris apartment.

_1882.jpg)

John Singer Sargent, Lady with the Rose (Charlotte Louise Burckhardt), 1882. Oil on canvas, 84 x 44 3/4 in (213.4 x 113.7 cm). Bequest of Valerie B. Hadden, 1932. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

James raved about Lady with the Rose (Charlotte Louise Burckhardt) (1882) as “the most brilliant of all Mr Sargent’s productions”. Standing so sweetly with her demure smirk in a black lace gown and holding up one white flower, the handsome 20-year-old daughter of a Swiss banker and an American mother is monochromatic except for the subtlest flesh tones and her blood-red lips. It is overall a rather sombre composition. It was for James, “a masterpiece of color as well as of composition, to possess much in common with a Velázquez of the first order, and to have translated the appearance of things into the language of painting with equal facility and brilliancy”. This “magnificent picture” offered James “the slightly uncanny spectacle of a talent which on the very threshold of its career has nothing more to learn”. Today it looks rather tame, conservative, almost too severely academic in its execution. It has none of the verve of other portraits by Sargent of the period. He is not showing off here as in his more painterly paintings. He just wanted to do a pretty picture of a pretty girl. It is pleasant and placid, surely competent, but it is hard to share or even understand what James saw in it. “My admiration for this deeply distinguished work is such that I am perhaps in danger of overstating its merits,” he confessed; “but it is worth taking into account that today, after several years of acquaintance with them, these merits seem to me more and more to justify enthusiasm.” His skills as an art critic were indeed limited and often unconvincing. He continued: “The face is young, candid, peculiar, and delightful. Out of these few elements the artist has constructed a picture which it is impossible to forget, of which the most striking is its simplicity, and yet which overflows with perfection. Painted with extraordinary breadth and freedom, so that surface and texture are interpreted by the lightest hand, it glows with life, character, and distinction, and strikes us as the most complete – with one exception perhaps – of the author’s productions.” Perhaps … perhaps. That criticism may apply to other works by the artist in question, but such gushing about this particular portrait of Charlotte Louise Burckhardt hardly seems justified.

In his day, Sargent was famous as a painter of women. He was always respectful of his feminine clients, perhaps too respectful. One often senses indifference on his part. He rarely expresses the same enthusiasm found in his portraits of men. Erudite and worldly, Sargent was thoroughly charming. And he could be quick. As has been mentioned, he could capture a vivid likeness in one sitting. Accuracy was a specific goal. “The gift that he possesses he possesses completely – the immediate perception of the end and of the means,” James observed. “Putting aside the question of the subject … the highest result is achieved when to this element of quick perception a certain faculty of brooding reflection is added … the quality in the light of which the artist sees deep into his subject, undergoes it, absorbs it, discovers in it new things that were not on the surface, becomes patient with it, and almost reverent, and, in short, enlarges and humanizes the technical problem.” As Erica E Hirshler argues in her essay Les Parisiennes in the Met’s handsome catalogue, Sargent was a painter of remarkable women. However, they were not goddesses. Like his fellow American artist Thomas Eakins, he had difficulty painting a pretty girl. The Met devotes one room to portraiture of other fashionable Parisian ladies by other fashionable painters (Carolus-Duran, Manet, Renoir, Whistler and others) to provide historical context for Sargent’s contributions to the genre. Their influence echoes throughout the exhibition. He drew from a vast coven of formidable, imperious but plain society dames such as Frances Sherborne Ridley Watts, Margarette Elisabeth de Ganay, la Vicomtesse de Police de Saint-Périery, Edith Foster Vickers, and Countess Louis de Scey-Montbéliard. They were not unlike his own mother. Yet all the expensive clothes in the world cannot hide their apparent lack of physical charms. Or is it the costumes that are so unflattering? He did not exist merely to kowtow to the vanity of his sitters. Sargent was not always kind to them, but he portrayed them invariably free of even the slightest glimmer of caricature. The wealthy bourgeois mother in Fête Familiale (The Birthday Party) (1885) has the beefy forearms of a charwoman. Sargent was clearly more enamoured with the pile of white frills worn by Margaret Stuyvesant Rutherfurd White than by her stern face. Alice Sidonie Vandenburg (Mrs Harry Vane Millbank) and Kate A Moore appear a bit too coquettish for their years. These women’s chief demand was that their portraits reflect their status within society. Too often Sargent appeared more interested in costume than countenance. Glamour was more often determined by the richness of the garments than by the paucity of allure in the faces.

Sargent’s sexual preferences may have been an obvious secret. Men seem not to have been intimidated by the debonair witty young painter. They felt that their wives, daughters and mistresses were safe with the confirmed bachelor. James described Sargent as “civilized to his fingertips”. He was always professional with his subjects. He was a grand master in the gentle art of intellectual seduction. Several of these ladies became his friends but never lovers – even if they longed to be otherwise. He may not have acted on his homoerotic impulses either. No scandal of the heart was ever connected to Sargent during his lifetime. And he frequented society where gossip was like mother’s milk. Discretion was a virtue he upheld especially after Oscar Wilde’s fall in 1895. Painting by its very nature was a sensual act for Sargent.

Sargent and Paris does have a definite queer vibe. The “male gaze” is much maligned at present. But what of the gay male gaze? The exhibit includes numerous flattering portraits of distinguished gentlemen with remarkable facial hair. (Smooth-skinned James sat for him more than once after the painter moved to England.) Among the best of his masculine pictures is the bust of his fellow student, the clean-shaven Albert de Belleroche with his chiselled features and thick neck, ruggedly painted à la Goya about 1883. There exist other striking paintings and drawings of the Welsh count by Sargent, including one rather campy 1882 picture of the rakish gent in a jauntily tilted fur hat so there may have been more than just a passing fancy between the two. Sargent has lately become an icon of LGTBQ+ politics, not necessarily something he would have pursued or welcomed any more than James would have. There is no evidence that Sargent ever discussed his same sex proclivities. He hid his private life so completely. He always remained firmly in the closet. Yet he obviously preferred men to women. The discovery in 2017 of startling male nude drawings Sargent left with Gardner led to the exhibition Boston’s Apollo: Thomas McKeller and John Singer Sargent at her museum in 2020. Much has been made recently of the Des Moines Metro Opera production of American Apollo, Damien Geter’s opera of an alleged affair between the painter and his proletarian Black male model McKeller, an elevator operator at the luxurious Hôtel Vendôme and later a postal worker. There is not a shred of evidence that they consummated their relationship, but there is no question that Sargent felt deep affection and admiration for this muscular working man. Further proof of his attraction lies in his unexpectedly frank portrait of McKeller now in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

Of course, that all belonged in Sargent’s late career, but this homoerotic tension is evident throughout Sargent and Paris, especially on one wall in the first room devoted to three disquieting men’s portraits. The subject of A Male Model Standing Before a Stove (c1875-80) challenges the viewer with his direct rude nude physicality. Only a convenient brown leather posing strap prevents him from going full monty. It is the last thing one expects to see by the celebrated chronicler of genteel Edwardian high society. It is a brutal crass picture that refuses to be ignored. The rough young street tough in the virile pair of cocky pictures that flank that nearly naked man, Head of a Male Model (c1878) and Man Wearing Laurels (1874-80), bears an alarming resemblance to the American pop singer Benson Boone. Obviously a favourite of the artist, the handsome, slightly effeminate lad shows up elsewhere in the exhibition, notably in Young Man in Reverie (1876), his dark curly hair and skin against a stark whitewashed wall. Sargent’s model Countess Louis de Scey-Montbéliard (Winnaretta Singer), heiress to the Singer sewing machine fortune, never hid her lesbianism despite two well-connected marriages; and an apparent Sapphic air permeates the boyish looks of Sargent’s childhood friend “Vernon Lee” (Violet Paget). The possibly lesbian writer in her pince-nez and starched white collar looks surprisingly like the British bisexual poet Richard Le Gallienne or even the repressed Irishman William Butler Yeats (who also sat for Sargent). The three all bore the same pale aesthetic countenance.

John Singer Sargent, The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit, 1882. Oil on canvas, 87 3/8 × 87 5/8 in (221.9 × 222.6 cm). Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Gift of Mary Louisa Boit, Julia Overing Boit, Jane Hubbard Boit, and Florence D. Boit in memory of their father, Edward Darley Boit.

As the few telling examples in Sargent and Paris prove, Sargent was also a master of painting boys and girls. Look at the charming Neapolitan Children Bathing (1879). The little youngsters’ wet on wet naked bodies virtually glisten in the hot Italian summer sun, they are so nimbly painted. There is no disconnect as between the Pailleron brother and sister among the four girls in the enormous and daring The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit (James called it “The Hall of the Four Children”) of 1882. James, who knew the Boits, described the picture as capturing a “happy play-world of a family of charming children”. He called it simply “the superb group of the children of Mr Edward Boit”. Their father was a Harvard-educated lawyer who left his practice to pursue painting in Paris. His wife Isa’s inheritance, amassed from Boston’s lucrative China trade, allowed them to live comfortably there. Their wealth is most apparent in the painting by the pair of enormous blue and white Japanese vases. They bring to mind George du Maurier’s 1880 Punch cartoon of a young bride, who on examining her new blue and white Japanese teapot, tells her Oscar Wilde-like husband: “Oh, Algernon, let us live up to it!” (The Boit’s original fragile porcelains did not make the long trip from the Boston Museum of Fine Arts to the Met as did the picture.) One of the most extraordinary portraits of the age is actually four. It broke all the rules of western painting. It was as radical as recent portraits by Degas. “The treatment is eminently unconventional,” said James, “and there is none of the usual symmetrical balancing of the figures in the foreground.” It has the immediacy of Japanese colour woodcuts recently discovered by the west as well as the artful casualness of Velázquez’s Las Meninas (c1656), that complex portrait of the Infanta and her entourage that Sargent had discovered years before at the Prado. (The inclusion of his copy of the famous Spanish painting, as well as one after Hals’ 1616 The Banquet of the Officers of the St George Civic Guard from 1880, reinforces Sargent’s great debt to his predecessors in this picture.) It also owes much to the influence of contemporary photography. The incongruous composition should not work but does.

This quartet of maids in waiting – Julia, Mary Louisa, Jane and Florence – ranged in age from four to 14. Pert little Mary Louisa happily poses for the painter in the deep space of the dimly lit foyer of the family’s Paris apartment as does the youngest who looks up momentarily from her dolly directly at him; the two older modest, more self-conscious sisters prefer to stand in the back flanked by the subtly rendered towering Japanese vases and the slash of a crimson screen. Twelve-year-old Jane was perfectly content to fade into the shadows. Sargent put down on the canvas Julia’s baby doll in a flurry of pink and white strokes as if the child had difficulty holding it still. The identical starched pinafores provided the master with another opportunity to play with the rigors of painting with white. James was rapturous: “When was the pinafore ever painted with that power and made so poetic?” Sargent captures beautifully the glint on the polished surfaces of the vases and black leather shoes with more swift thin bits of white. They are securely grounded to the floor as he so convincingly captures the form and weight of the four figures. It was all an extraordinary achievement for a man of only 26. For James, “the naturalness of the composition, the loveliness of the complete effect, the light, free security of the execution, the sense it gives us of assimilated secrets and of instinct and knowledge playing together” all added up to an “astonishing” painting. It is all as confidently painted as Renoir’s equally unconventional Madame Charpentier and Her Children (1878) that may be found in the exhibit for comparison. The brushwork and colour scheme are refreshingly similar but hardly identical.

John Singer Sargent, Dr Pozzi at Home, 1881. Oil on canvas, 79 3/8 × 40 1/4 in (201.6 × 102.2 cm). The Armand Hammer Collection, Gift of the Armand Hammer Foundation. Hammer Museum, Los Angeles.

The most imposing and intriguing pose in the show is that of the swaggering French surgeon, gynaecologist and art collector Dr Samuel Jean Pozzi. The picture pulsates with sexuality. It was quite unusual to depict a man so informally and provocatively in his robe de chambre (rather than a proper dark formal business suit) and a blood-red one at that. It implies that he is either going to bed or just getting up. Maybe he is going straight to Hell. The scarlet background in Dr Pozzi at Home (1881) indicates infernal fires of all eternity blazing in his boudoir. There are no cool colours here, no blues, no greens. Dashing Dr Pozzi sports a Beelzebub-like beard and moustache and an almost otherworldly devilish glance. His Mephistophelean stance is as theatrical and monumental as that of AY Golovin’s 1912 portrait of opera singer Fyodor Chaliapin as Boris Godunov. James compared Pozzi’s demeanour to that of the English painter Anthony van Dyck’s 17th-century noblemen. Sargent shows off the long tapering fingers of the surgeon’s delicate, exquisitely artistic, skilful hands with the left jauntily placed on one hip and the other diddling with the opening of the robe. It is an aggressive arrogant pose reflecting this bon vivant’s own intense sense of self-importance. Attention must be paid. Sargent did not dare exhibit the alarming picture in France, but it was the first one he showed at the Royal Academy of Arts in London. Critics have pointed to the phallic tassel dangling in the front from the waist and often compare this bold portrait in red to pictures of popes and cardinals. But the doctor was a real devil. Although married with three children, Pozzi was quite the ladies’ man. According to the British curator James Payne on his website Great Art Explained, the famous gynaecologist was referred to asL’Amour Médecin or Dr Love. Among his many alleged conquests were legendary actresses Sarah Bernhardt and Gabrielle Réjane, as well as the widow of the composer Georges Bizet. A disgruntled patient murdered him in 1918 before shooting himself, because he believed the surgeon had left him impotent. He may also have been a bit of a saint: Pozzi defended Alfred Dreyfus when other Frenchmen were damning him as a traitor. The good doctor came to the poor man’s aid after a rightwing journalist shot the disgraced Jewish officer in the arm. English writer Julian Barnes based his novel of La Belle Époque, The Man in the Red Coat (2019), specifically on this stunning portrait. He observes that the gown’s frontal tassels look like a “bull’s pizzle”.

Naturally, everything in Sargent and Paris leads straight to one masterpiece, the formerly terrible Mme X. Hardly anyone today knows the once glamorous young American-born socialite Virginie Amélie Avegno Gautreau, wife of a wealthy but boring French banker twice her age, except by this famous painting. Sargent may have approached Pozzi for an introduction to Mme Gautreau. (The curators of Sargent and Paris insist there is no proof that the doctor and the lady had any love affair as has been long rumoured.) It seemed as if every artist in Paris wanted to paint or sculpt her, but she turned them all down until she met Sargent through a mutual acquaintance. He pursued her for months until she finally gave in. He felt she was perfect for his self-declared “prodigious talent”. She was of French Creole descent, a child of rich parents in New Orleans, and moved to Paris with her mother after her father died fighting on the Confederate side during the civil war. He had been a shrewd real-estate investor; and her mother’s family amassed their vast wealth in cotton, indigo and sugarcane from slave labour. Like a Gilded Age Kim Kardashian, Gautreau became famous for being a “professional beauty”. She did not have to do anything but look pretty. And everything she did do became tabloid fodder. Certain Parisians resented this nouveau riche American upstart’s celebrity as much as they did Sargent’s.

John Singer Sargent, Madame Gautreau Drinking a Toast, 1882-83. Oil on panel, 12 5/8 × 16 1/8 in (32 × 41 cm). Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston.

It must be understood that the portrait was not a commission: he sought her out. He was intrigued by her red hair and white skin and long lovely neck. He looked forward to “tackling the portrait of a great beauty”. He added: “She has the most beautiful lines.” She appeared to be the ideal of the modern woman. Sargent wanted to create a painting specifically for the Paris Salon that would cause a sensation. And it did … but hardly in the way he expected. She finally surrendered to his entreaties. But it all had to be done at her convenience. She had him come up to Les Chênes, the family chateau in Paramé, Brittany. Posing bored her. Sargent wrote disdainfully of “the unpaintable beauty and hopeless laziness of Madame Gautreau”. The curators report that Sargent made more preliminary studies for this painting than for any other of his career. That may have been due to her lack of cooperation rather than to any attraction he may have harboured towards his subject. He was struggling to figure her out. The hasty preliminary watercolour Madame Gautreau (Madame X) (c 1883) and clumsy oil sketch Madame Gautreau Drinking a Toast (1882-83) lack the polish, poise and finesse of the final portrait. By contrast, he did attain an exquisite profile drawn in thin pencil with Beardsleyesque brevity. He was determined then to capture that haughty patrician contour of the face on canvas.

As her photographs attest, Mme Gautreau was not a classical beauty. She had a flat forehead, a large nose, dominant ears, a prominent chin, a small mouth and beady eyes. With her wide exposed alabaster shoulders and fleshy arms, there is even a hint of masculinity about her. And yet her portrait is stunning. Just try to turn away. Sargent literally stripped her to the basics. It was all so pure in its execution. He discarded the superfluous. There is no unnecessary detail to distract from her lovely face and form. He had her lean on the right rather awkwardly, uncomfortably against a table, and lifting the skirt a bit with the left hand while clutching a closed black lace fan. She herself accepted the pose and the low-cut gown with its black velvet bodice and black satin skirt that he picked out for the picture. Even the fallen strap met with her approval. The dress fully caressed and emphasised the curves of her enticing hour-glass figure. Despite her indifference to the whole tedious process, Mme Gautreau could not have been happier with the result and wrote to a mutual friend: “Mr Sargent made a masterpiece of the portrait.” Sargent wanted to make waves at the Salon on 30 April 1884, but he nearly sank the ship. At 28, he woke up the next morning to find himself infamous.

The portrait was merely one of several thousand entries, all tightly hung by genre en masse for the eager public. And yet it stood out. The Met gives some idea of the vast competition that year by filling a wall with a projection of other works in the exhibit that surrounded but did not dwarf Sargent’s entry. The Salon’s policy was not to identify the subjects by name, so Sargent called it “Madame ***.” But everyone knew exactly who she was. Disdain and admiration were hurled at him and her. Crowds encircled the picture, expressing their shock and awe at its flaws and, yes, its virtues. Women jeered at it: “Oh quelle horreur!” To shamelessly borrow the Russian poet VV Mayakovsky’s phrase, it was like a “slap in the face of public taste”. What one did behind closed doors should stay behind closed doors, they thought. It was just too, too shocking to bare one’s milky white shoulders as she did in public. It was an age when an exposed ankle was looked on as something shocking. Nothing was more erotic than a plucked lock of hair. It stunned the French critics who saw only vulgarity in her brazen pose. High-society women should not be so bold, so immodest. They found the impudent, improper Mme Gautreau insufferable. All proper ladies were discreetly covered up nearly to their chins. It was all so hypocritical. Plump, overripe nudes did not bother Sargent’s critics if such ladies were presented in the buff within classical mythological or historical context. Allegory was acceptable. Even depictions of prostitutes were at times allowed. But they could not tolerate a lady of fashion putting on such unguarded display as in Sargent’s picture. He had gone too far this time. The papers published nasty caricatures of the American hussy with the long neck, low neckline and snooty attitude. There was just too much skin for Madame Grundy. Too much décolletage.

And that strap! That wanton strap! It fell so casually, so seductively off her right shoulder. It appeared to some as if her dress was about to fall from her body or had just been yanked in the throes of passion. Had she not time enough to fully pull it up again? It was upheld by just two slender strands to make disrobing all the easier. Some wondered if she was wearing any undergarments. Her apparent state of undress branded Mme Gautreau publicly as a woman of loose morals. There were all sorts of invented salacious scenarios for what was really going on in that picture. No doubt another nod to Velázquez and Manet, Sargent had her stand in a shallow space against a neutral tone that was also indicative of geishas in Japanese colour woodblock prints then all the rage. (He painted over the originally dark background.) She tinted her hair a mahogany hue and drew on her eyebrows and applied chlorite of potash powder and arsenic, which gave her already fish-belly white skin its lavender, almost cadaverous tint when only courtesans such as la Dame aux Camélias so highly painted their faces. Mme Gautreau bore the pallor of the consumptive. Sargent called it a “blotting paper colour all over”. Her be-rouged her ears suggested to at least one commentator the flush of postcoital bliss. Her heavy makeup may have been fine in the evening, but in daylight quelle horreur!

Everything that went into the painting added to what some observers viewed as the blatant predatory nature of this conceited temptress. One can barely notice in the hair a teeny tiara in the shape of a crescent moon, the classical symbol of Diana the Huntress. It might also imply that she was a lady of the night despite her sparkly wedding ring indicated by a discreet fleck of white paint. (Was that proof of her marriage vows after the fact, like the readjustment of the strap? It is hard to tell in the only surviving photograph of the original whether she was always wearing it.) Further, the slim table legs sprout winged sirens, those mythical creatures whose song sent unsuspecting mariners to their deaths. All the details made madame the original vamp long before it became a Hollywood cliche. Just a solitary strap holds up the dress in an abandoned duplicate of this then disgraceful portrait borrowed from the Tate Gallery in London. And there is no convenient wedding ring on the left hand of that other portrait of Mme Gautreau.

Both painter and subject were devastated by the public outcry the picture encountered. They were completely baffled, unprepared for such open hostility toward the work. At least both were considered culpable. There was no double standard here as there was decades later in the “wardrobe malfunction” that destroyed Janet Jackson’s reputation but not Justin Timberlake’s. Not all the public fury over the two culprits can be attributed to mere French chauvinism. (Sargent was equally burned later by conservative English prejudice. Americans had no problem with his cosmopolitanism.) Some critics were more than eager to tear down the American’s unbridled ambition a few pegs. One journal called the painting “simply offensive in its insolent ugliness and deviance of every rule of art”. They could not abide how two foreigners could flout conventional middle-class morality and throw it back in their faces.

It is now difficult to understand exactly what all the fuss was about. His old friend Vernon Lee suggested Sargent only had himself to blame. She said he always had a “predilection” for “the bizarre and outlandish”. He was obsessed with capturing “the ‘strange, weird, fantastic, curious’ beauty of that peacock-woman”. Mme Gautreau with her mother in tears came to Sargent’s studio and begged him to withdraw the picture. He refused. When the show closed and it was returned to him, he capitulated and hastily repainted the strap firmly placed on the shoulder. James summarised the whole imbroglio as “a kind of unreasoned scandal –an idea sufficiently amusing in the light of some of the manifestations of the plastic effort to which, each year, the Salon stands sponsor”. After all, the infallible committee had refused the impressionists back in 1863.

The aftermath was not as horrid as legend makes it out to be. As Herdrich reveals in the Met catalogue, Mme Gautreau quickly had a change of heart and began to capitalise on her notoriety. She did not permanently fall from grace in Parisian high society as has often been reported. On the contrary, she soon regained her status as one of the prominent “professional beauties” in the capital. As Lee pointed out, all the belligerent commotion the picture stirred nearly crushed Sargent. “Women are afraid of him,” she wrote, “lest he should make them too eccentric looking.” His commissions consequently dwindled; and his fellow expatriate James encouraged him to seek refuge in London. Perhaps the English would be more hospitable to him. He did not flee Paris overnight in shame as the story goes. Sargent had been thinking of going for some time before the Madame *** affair and had already found a few commissions for portraits during a visit in 1884, but he had his doubts about relocating since John Bull considered his work “beastly French”. The British did not entirely embrace him when he did arrive in London in 1886. It took him time to establish himself as the leading society painter in the capital. James recognised that his friend had reached a crossroads in his distinguished carrier. As the writer wondered the following year, Sargent “knows so much about the art of painting that he perhaps does not fear emergencies quite enough, and that having knowledge to spare, he may be tempted to play with it and waste it”. He need not have worried. Talent will out. He made a sensation when he visited the US in 1889 as the guest of the Boits. He painted 20 portraits in just that one year there. In the long run, the “Madame ***” scandal bolstered his international reputation. Wilde’s famous quip applies to Sargent’s reputation: “There is only one thing in the world worse than being talked about, and that is not being talked about.” He continued to thrive and went on to do the portraits of robber and real barons on both continents. He was earning the equivalent of $130,000 a picture when, in 1907, he turned his back on portraiture to concentrate on painting murals and outdoor scenes.

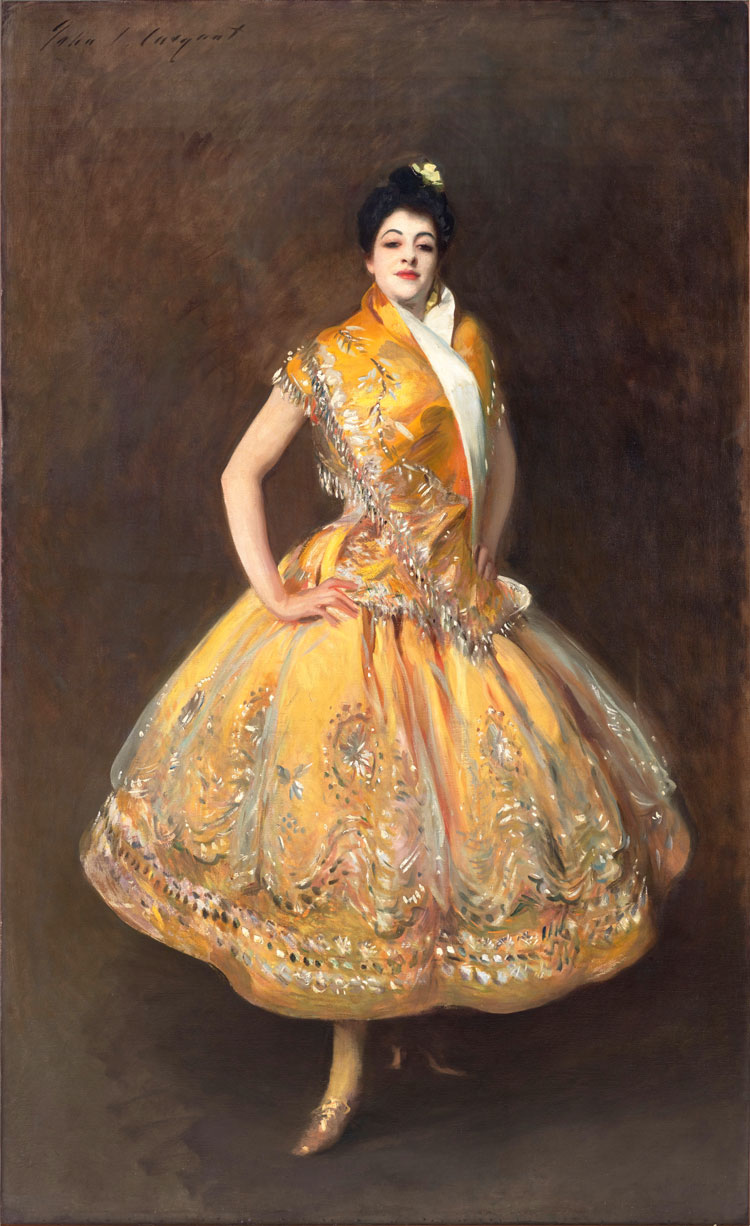

John Singer Sargent, La Carmencita, c1890. Oil on canvas, 90 3/16 × 55 1/8 in (229 × 140 cm). Musée d'Orsay, purchase from John Singer Sargent, 1892.

He could never get Paris out of his system. Sargent quite suddenly redeemed himself with the French in 1892 when the government purchased his life-size portrait of the internationally known Spanish dancer La Carmencita (Carmen Daucet Moreno) (1890) in all her stage finery for the Musée du Luxembourg with the expectation that it might one day hang in the Louvre. It was the first major work by the painter to be exhibited in any public collection. It was only appropriate that he, a lover of all things Spanish, return to the art that had been the source for his popular El Jaleo. When Sargent saw Moreno perform in 1889, he knew he had to paint her. He perfectly captured her impudent pose and cheeky grin. Carmencita may well have been the very first woman to appear in front of Thomas Edison’s motion picture camera for commercial use, also in 1892. She had recently completed a successful engagement at Koster & Bial’s Music Hall in New York City. A short silent film of her performing in the same spangled yellow costume is preserved in the Library of Congress. Singer and Paris appropriately and unfortunately concludes with that inferior picture. It is sadly anticlimactic. La Carmencita does not inhabit the same sphere as Madame X. She is literally upstaged by her dress. That absurd yellow gown, while graceful in performance, was the sort of fashion that Aubrey Beardsley would soon mercilessly parody in The Yellow Book and elsewhere. It is best to stop abruptly and return to Madame X.

John Singer Sargent, Madame X (Madame Pierre Gautreau), 1883–84. Oil on canvas, 82 1/8 x 43 1/4in (208.6 x 109.9cm). Arthur Hoppock Hearn Fund, 1916. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

It is a shame there are not more drawings and watercolours in the exhibition. No one can fully understand Sargent as an artist without knowledge of this other art. Of course, there are always inherent difficulties in exhibiting such vulnerable, volatile works for any extended period. They tend to fade. Nevertheless, Sargent was a master of both media. He exhibited a sensuous mastery of pencil, pen and charcoal that could so quickly define a body with the most convincing, alluring curves through a few confident turns of the wrist. He possessed the dexterity to fix a resemblance with the least concerted effort. He fully redefined the watercolour. The adroit application of thin washes in his oil paintings was perfected in these other works on paper; and he brilliantly employed the white of the page as another colour. Arguably there was no greater American watercolourist than Sargent. Perhaps only Winslow Homer comes anywhere near him.

The artist was always fond of that much-abused painting of Mme Gautreau and proud too. He posed with it in his atelier. He finally began exhibiting it internationally in 1905. It hung in his studio until 1916 when he finally sold it to the Met. Mme Gautreau had died the year before in Cannes. Sargent could now safely display it in a public collection. “I suppose it’s the best thing I’ve ever done,” he confessed to the museum’s director at the time. However, he insisted that they keep her identity secret. While James had referred to it in Harper’s as “Madame G,” it now became “Mme X”, a name that has entered the language to denote any woman of ill repute. “It is a work to take or to leave, as the phrase is,” James concluded, “and one in regard to which the question of liking or disliking comes promptly to be settled. It is full of audacity of experiment and science of execution; it has singular beauty of line, and certainly in the body and arms we feel the pulse of life as strongly as the brush can give it.” Madame X will remain a high point of the Met’s collection long after Sargent and Paris has been dismantled. Yet no one should miss this superbly orchestrated recreation and visual evaluation of what led up to its initial appearance in Paris. One needs to visit the exhibition at least twice or thrice to fully take in all its abundant splendours.

• Sargent: The Paris Years (1874-1884) will be at the Musée d’Orsay, Paris, from 23 September 2025 to 11 January 2026.