Whitechapel Gallery, London

7 October 2020 – 10 January 2021 (Reopening 3 December 2020.)

by JOE LLOYD

I doubt there has ever been so much art crammed into the Whitechapel Gallery. Kai Althoff Goes With Bernard Leach, the first institutional show in the UK of the Cologne-born, New York-based Althoff (b1966), is stuffed to the gills. Althoff is difficult to categorise, a jack-of-all-trades. He has produced dance music, squatted in galleries and acted with Isa Genzken in a rambunctious comedy film. In recent years, however, the focus has been on paintings, drawings and collages, realised in a disparate array of methods, formats and materials.

Kai Althoff. Hakelhug, 1994. Clay sculptures on sisal rug, two antique wooden beams from a loom, glass panel, wool, green wooden bucket, 178 x 247.5 x 32 cm. View of work at Galerie Christian Nagel, Cologne, 1994. Photograph by the artist.

The present exhibition is no exception. A pick-and-mix selection of Althoff’s work might include vaguely neo-expressionist religious scenes, subdued landscapes inhabited by puck-faced fairy folk, sketches of cartoon-like characters woven in cotton and felt, and thorny abstract collages assembled from lacquer and gift wrap. They often feel like glancing excerpts from a narrative, the remainder of which we will never see. Many possess a certain drabness, as if left to moulder in an abandoned house. One of Althoff’s talents is the ability to render colour that is at once bold and faded, implying a former state of splendour that never occurred. Another is a penchant for turning DIY construction into a virtue. Althoff compiles bits and bobs into peculiar wholes. He might stick frilly lace on an otherwise austere abstract, split a street scene between two pebble-shaped canvases or draw on top sheets of paper barely held together by tape. Even his duller pictures are materially exciting.

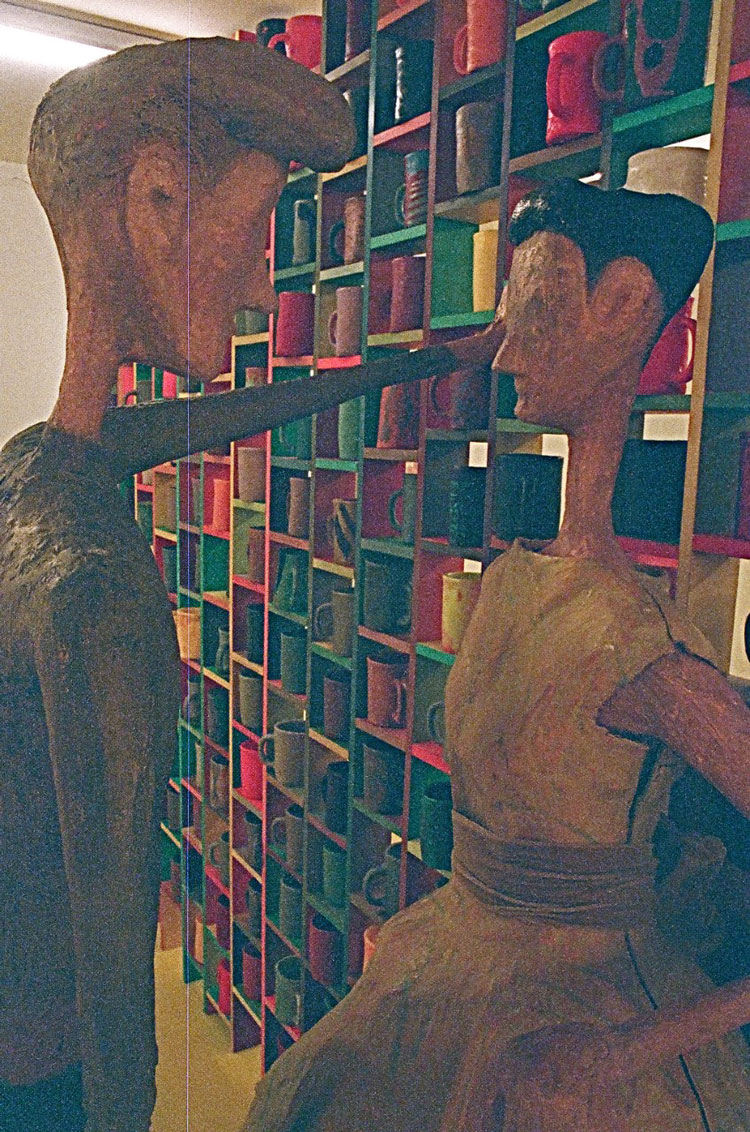

Kai Althoff. Untitled, 2011. Plaster sculptures painted with oil paint, pigmented and painted wax mugs, poster painted and waxed shelving, dimensions variable. Exhibition view at Gladstone Gallery, New York, 2011. Photograph by the artist.

Like many painters who emerged at the tail end of the 20th century, Althoff’s style and subject matter seems haunted by the art of 100 years prior. But I am not sure that high art offers the clearest route into Althoff’s bizarre world. His work seems instead to digest the half-remembered visual detritus with which human experience is strewn: album covers, psychedelic posters, comic strips, illustrated children’s books. Some works have the lucid colouration of stained-glass windows in a postwar church. A pair of 2014 oil and enamel works showing pigs hidden within brown grooves resemble the sort of folk art you might find in a rustic gasthaus.

Kai Althoff Goes With Bernard Leach, installation view (detail), Whitechapel Gallery, London, 7 October 2020 – 10 January 2021. Photo: Polly Eltes.

Althoff is very good at evoking place. He has installed a translucent tarpaulin canopy in the Whitechapel’s main hall, halving the room’s height. It is scattered with leaf litter, so that the room resembles a roofless house, hastily covered over to keep out the rain. Beneath the canopy, works hang in apparent disorder. There are smudged pencil lines on some of the walls, as if no one cared too much for neatness. A polystyrene room divider bends across the hall in an apparently arbitrary arc. Whitechapel has been turned into the sort of gallery you sometimes stumble across in Europe’s easternmost regions, stuffed with a willy-nilly arrangement of local art unchanged since the 1990s.

Visiting the exhibition at opening time, I was alone for a few minutes. The experience was disquieting, as if I had trespassed into the private hoard of a collector with sadistic tendencies. Althoff’s imagination can be cruel. In Das Fleisch seiner Knochen (2002), a semi-nude man’s knees rot away to reveal the bones beneath. The spectre of brutality lingers everywhere. Untitled (Grazing) (2001) sees young men grovelling on their bellies. A 1997 drawing has one man in a conductor’s cap bestride another, clutching him by the back of his jacket. Even Althoff’s calmer works seem to live in a haunted demimonde, where sinister goings-on occur behind tattered curtains.

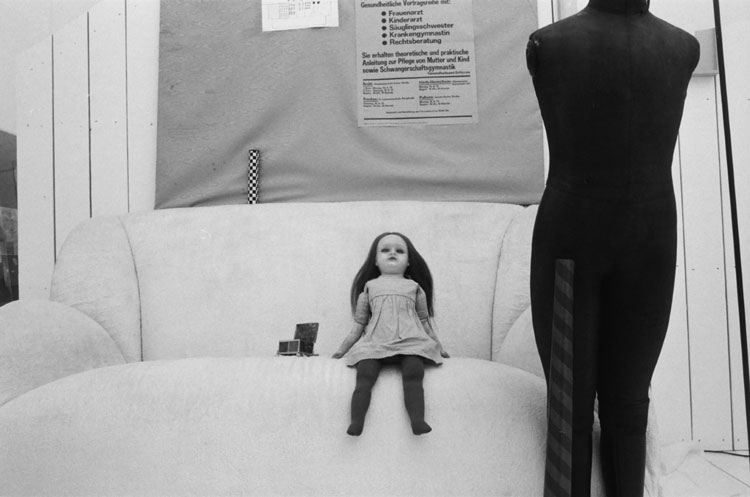

Kai Althoff, Untitled. 2011. Sofa, screen, mannequin, silk covered board with poster and drawing, kaleidesope, doll, dead locusts, ormolu box and emerald stone brooch, gift wrap paper lined cardboard tube, lamp, dimensions variable. View of work at Kai Althoff: und dann überlasst mich den Mauerseglern (and then leave me to the common swifts), Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2016. Photo: Yair Oelbaum.

Althoff has long held a reputation as a provocateur. He once urinated on paintings before packing them off to buyers. At Kai Althoff: and then leave me to the common swifts, his 2016 Museum of Modern Art retrospective, he borrowed works from collectors and then left them lying unseen in crates. Although his provocations are mostly directed at the art establishment, he likes to needle audiences, too. One gouache from 1994, in a sallow, realist mode, sees a baker raise his right hand in what might be a Heil Hitler salute, willing or reluctant; a pale wad of dough sits on his windowsill like a pound of flesh. Untitled (Olympic Gestures) (1985) includes two study-like depictions of a strong-jawed Aryan type wearing an Olympic laurel. The artist has spattered the paper with faeces, possibly his own. Althoff seems to claim the entire history of images as permissible subject matter.

This notion came under strain in 2018. A sequence of works displayed at New York’s Tramps gallery was accused of drawing on orientalist stereotypes. Pieces from that series here reveal a complicated picture. Althoff undeniably draws on eroticised cliches: rows of submissive courtesans, recumbent young men, nude bodies prodded by the spears of warlords. Yet, as often as not, he often shows east colliding with west – a fearsome oni munching on a man is clearly based on Goya’s Saturn – or dispenses with east Asian aesthetics altogether. Althoff seems less engaged in perpetuating particular stereotypes than drawing on visual history without limit. Whether he warrants the licence to do so remains an open question.

Kai Althoff Goes With Bernard Leach, installation view (detail), Whitechapel Gallery, London, 7 October 2020 – 10 January 2021. Photo: Polly Eltes.

The strangest provocation at Whitechapel sits upstairs. In the exhibition’s third room, Althoff has installed a custom-designed vitrine showcasing more than 30 works by Bernard Leach (1889-1979), who is regarded as the “father of British studio pottery”. These are fabulous objects: jugs, plates, urns, bowls and even buttons, spun with earthly beauty. In the exhibition’s press material, Althoff calls Leach his “idol”, and one could draw parallels between their embraces of imperfection and materiality. But so much else about their respective practices is removed. Perhaps Althoff is being impish – Leach, who learned his technique in Japan, has been accused of appropriation. But here, as with so much in Althoff’s practice, you get the sense that he would rather the connection remain elusive.

The first of its kind, this vast show is a stunning tour of the realism movement of the 1920s and 30...

Maggi Hambling: ‘The sea is sort of inside me now … [and] it’s as if...

Maggi Hambling’s new and highly personal installation, Time, in memory of her longtime partner, To...

Caspar Heinemann takes us on a deep, dark emotional dive with his nihilistic installation that refer...

Complex, multilayered paintings and sculptures reek of the dark histories of slavery and colonialism...

Shown in the context of the historic paintings of Dulwich Picture Gallery, Rachel Jones’s new pain...

William Mackrell – interview: ‘I have an interest in dissecting the my...

William Mackrell's work has included lighting 1,000 candles and getting two horses to pull a car. No...

Marina Tabassum – interview: ‘Architecture is my life and my lifestyle...

The award-winning Bangladeshi architect behind this year’s Serpentine Pavilion on why she has shun...

A cabinet of curiosities – inside the new V&A East Storehouse

Diller Scofidio + Renfro has turned the 2012 Olympics broadcasting centre into a sparkling repositor...

Plásmata 3: We’ve met before, haven’t we?

This nocturnal exhibition organised by the Onassis Foundation’s cultural platform transforms a pub...

Ruth Asawa: Retrospective / Wayne Thiebaud: Art Comes from Art / Walt Disn...

Three well-attended museum exhibitions in San Francisco flag a subtle shift from the current drumbea...

This dazzling exhibition on the centenary of John Singer Sargent’s death celebrates his versatile ...

Through film, sound and dance, Emma Critchley’s continuing investigative project takes audiences o...

Rijksakademie Open Studios: Nora Aurrekoetxea, AYO and Eniwaye Oluwaseyi

At the Rijksakademie’s annual Open Studios event during Amsterdam Art Week, we spoke to three arti...

AYO – interview: Rijksakademie Open Studios

AYO reflects on her upbringing and ancestry in Uganda from her current position as a resident of the...

Eniwaye Oluwaseyi – interview: Rijksakademie Open Studios

Eniwaye Oluwaseyi paints figures, including himself, friends and members of his family, within compo...

Nora Aurrekoetxea – interview: Rijksakademie Open Studios

Nora Aurrekoetxea focuses on her home in Amsterdam, disorienting domestic architecture to ask us to ...

Kiki Smith – interview: ‘Artists are always trying to reveal themselve...

Known for her tapestries, body parts and folkloric motifs, Kiki Smith talks about meaning, process, ...

Frank Auerbach, Britain’s greatest postwar painter, has a belated German homecoming, which capture...

How Painting Happens (and why it matters) – book review

Martin Gayford’s engrossing book is a goldmine of quotes, anecdotes and insights, from why Van Gog...

Jonathan Baldock – interview: ‘Weird is a word that’s often used to...

As a Noah’s ark of his non-binary stuffed toys goes on show at Jupiter Artland, Jonathan Baldock t...

Helen Chadwick: Life Pleasures

Helen Chadwick’s unwillingness to accept any binary division of the world allowed her to radically...

Catharsis: A Grief Drawn Out – book review

To what extent can the visual language of grief be translated? Janet McKenzie looks back over 20 yea...

Radical Software: Women, Art & Computing 1960-1991

With more than 100 works by 50 artists, this show examines the pioneering role of women in computer ...

Dame Jillian Sackler, the art lover and philanthropist, has died aged 84...

Giuseppe Penone: Thoughts in the Roots

With numerous works created with the twigs, leaves, roots, branches and majestic forms of trees, thi...

Solange Pessoa: Pilgrim Fields

An olfactory orgy of marigolds, chamomile, grasses, sheepskins and kelp is arranged into a surreal l...

Christian Krohg: The People of the North

A key figure in Norwegian art, naturalist painter Christian Krohg wanted his art to bring social cha...

This comprehensive show charts the groundbreaking rise of the illustrated poster in 19th-century Fra...

Caspar David Friedrich: The Soul of Nature

This comprehensive show celebrating last year’s 250th anniversary of the Romantic painter’s birt...

A humongous survey of contemporary painting in Belgium shows a medium embracing the burden of its hi...