William Ludwig Lutgens. Joy Sauce in The Belly 3#, 2025. Installation view, Painting After Painting, SMAK, Ghent, 2025. Photo: Dirk Pauwels.

SMAK (Municipal Museum of Contemporary Art), Gent

4 April – 2 November 2025

by JOE LLOYD

Painting has been murdered. There are numerous suspects. Was it conceptual art, which looked down on painting as decorative and retrograde? Did the abstract expressionists slash it with a palette knife, after pushing it to exhaustion? Could it have been Marcel Duchamp with his readymades, or even photography, which battered away the brush’s claims to realism?

Yet whoever murdered painting bungled the job. The oldest artistic medium has a habit of bouncing back. Photography spurred modern painters towards new forms of observation. Conceptualism won one battle but soon encountered its own limits – and alienated some audiences for whom art is primarily an aesthetic object. The first signs of a turning tide came in the early 1980s, when Norman Rosenthal organised his seminal exhibitions of neo-expressionist painting in London and Berlin. But the last decade has seen a sea change. In 2014, the Museum of Modern Art in New York opened its first survey of contemporary painting in 30 years. Now painting is everywhere.

There are many reasons for this. With many museums facing mounting costs and austerity, figurative painting offers the surest public draw. In an internationalised environment, it offers a media franca. The materiality of painting contrasts with the digital dystopia in which we increasingly find ourselves. Then there is the tightening grip of the commercial art world on its institutional sibling. Painting has always remained the star of the market: it is harder to turn a performance piece into a commodity. Is it any wonder that so many young artists are reaching for their brushes?

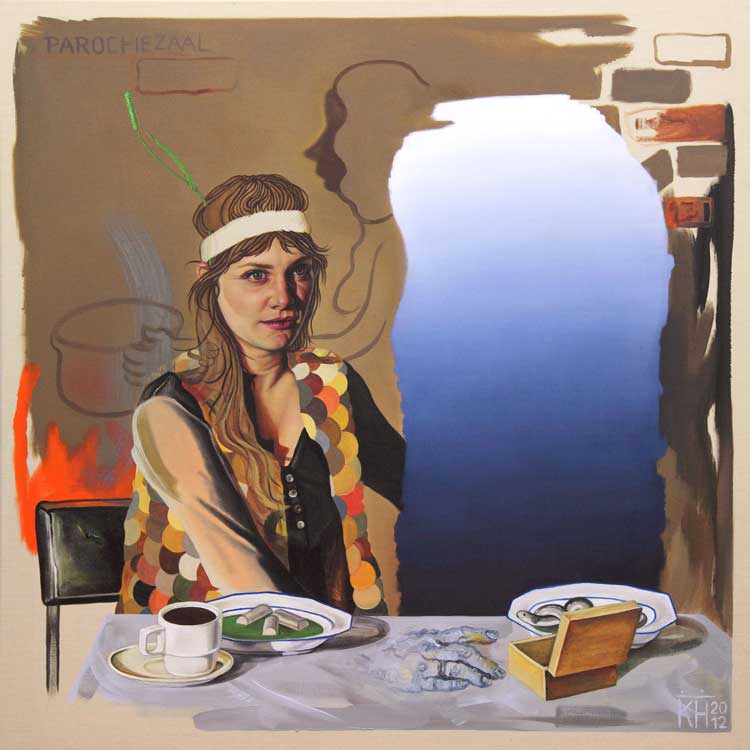

Kati Heck, Zum Teufel, Positionen!, 2012. Oil on canvas, 120 x 120 cm. Tim Van Laere Collection, Antwerp. Courtesy Tim Van Laere Gallery, Antwerp-Rome .

Painting After Painting is an attempt to capture this moment in time. It does so through the lens of the art being produced in one country, Belgium, though many of its 74 artists hail from elsewhere. Belgium has a storied painting tradition, reaching back to Jan van Eyck through to Michaël Borremans and Luc Tuymans: an illustrious roll of white men. These figures have had their dues. So, the curators decided to focus on artists from younger generations. The oldest painters here were born in the 1970s. Some are established figures; for others it is their first institutional showing. The majority of the works on show were executed in the last couple of years.

The result is an almighty, madcap sprawl. There is something for everyone, and probably a turnoff for everyone too. The paintings are grouped by loose, flexible themes – one deals with the impact of digital, for instance, another with identity – but it is rare to find two artists working in a similar idiom.

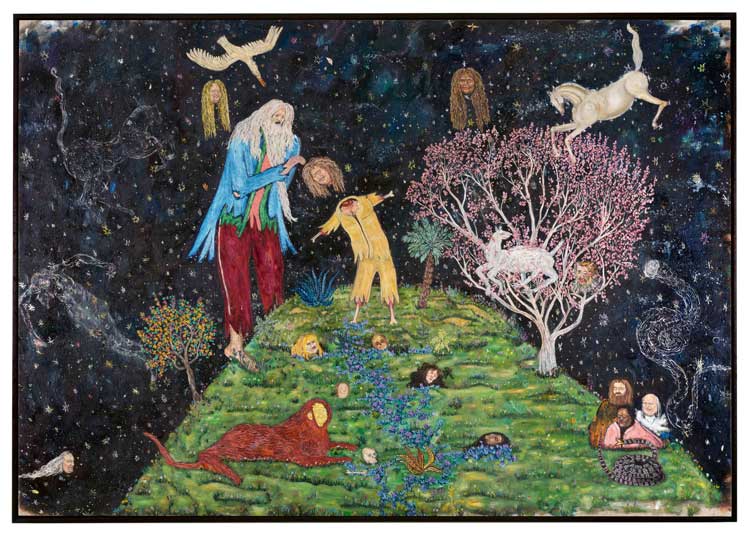

Bram Demunter, The Joke of the Bear, 2021. Oil on canvas, 170 x 200 cm. Private Collection, Belgium. Courtesy Tim Van Laere Gallery, Antwerp - Rome.

The practitioners will paint on almost anything: a marble slab (Pieter Vermeersch), a sheet of reflective glass (Carlotta Bailly-Borg), old supermarket fliers (Anne Van Boxelaere), a toilet seat (Michiel Ceulers). Helmut Stallaerts paints on jute and birch bark to create works that have a commanding physical presence. Henrik Olai Kaarstein’s Reputation 6 (2013) is daubed on a towel pilfered from one of those hotels in which no one ever spends a whole night; it faces Michael van den Abeele ’s Spaghetti/Jeans (2024), which was created by stretching denim across a canvas and then bleaching it to reveal wiggly lines.

This is one of several works that pushes against a strict delineation of painting. Natasja Mabesoone plays with print. Hannah de Corte uses marker pen on canvas, creating works that look more like textile panels than conventional paintings. Sometimes a painting is corralled into a mixed media work. William Ludwig Lutgens’s raucous Joy Sauce in the Belly #3 (2025) depicts a home office filled with bogeymen. Two hands in the foreground type on a laptop, the screen of which presents a video in which grotesquely attired zombies speak of their neoliberal imprisonment.

For all this experimentation with medium, paint applied to canvas still dominates. The exhibition’s first section gathers works that exist in dialogue with traditional forms of painting. A conventional mid-century idea held that painting was always advancing; after abstract expressionism, there was simply nowhere else to go. Painting After Painting posits that this progressive notion of art has been laid aside. As the exhibition text reads: “Artists no longer seek renewal in a break with the past, but rather in the creative reinterpretation of existing tradition.”

Anastasia Bay, fresco around SMAK’s ticket hall. Installation view, Painting After Painting, SMAK, Ghent, 2025. Photo: Dirk Pauwels.

Frederik Lizen boldly states his influences outright. His Jean Ai Assez (2020), named for Jean-Michel Basquiat, features a spray-painted list of inspirations. We see artists drawing on new objectivity (Yann Freichels), 19th-century realism (Bendt Eyckermans), Bosch and Bruegel (Sanam Khatibi), photorealism (Diego Herman), expressionism (Thom Trojanowski) and Minoan wall painting (Anastasia Bay, who has painted a fresco around SMAK’s ticket hall). There are some unexpected juxtapositions of modes. Mae Dessauvage’s Doll (2024), for instance, features an anime-like character depicted on four sides of a miniature gothic chapel. Jannis Marwitz’s The Raid (2021) churns up elements from Roman wall painting, Flemish Renaissance, new objectivity and Max Ernst into something that seems entirely novel.

Jannis Marwitz, The Raid, 2021. Oil on linen, 80 x 115 cm. Courtesy the artist and Trautwein Herleth, Berlin. Photo: GRAYSC.

Despite the predominance of adopting art historical models, many of the artists here are creating works that respond to contemporary developments. Technology is a perennial subject, although the works that treat it often suggest comment on art as well. Two walls are given over to Emmanuelle Quertain’s My address (2023), 467 small-format watercolours based on her browsing history. We see endless news clips and stock images from articles. These images grow sketchier as Quertain tires, echoing the familiar progress of becoming fatigued from doomscrolling. Korea-born Che Go Eun’s Diptych (2017) translates a pornographic YouTube advertisement she was served after moving to Belgium, exposing the online sexualisation of her Asian identity. A painting of the YouTube screen, featuring a posed nude, sits next to a twin without the text. Is online pornography the descendant of art history’s nudes?

Surveys of contemporary painting tend to insist on an angle: the return of figuration, the rise of technology, et cetera. Painting After Painting is refreshing in its lack of argument. It presents an abundance of art and lets visitors find their own way. But a few clear messages emerge from the morass. One is that painting has become globalised. Digital reproductions can be generated with an online search, and the same artists crop up across the developed world. Within the mainstream of contemporary art at least, the idea of national style is dead.

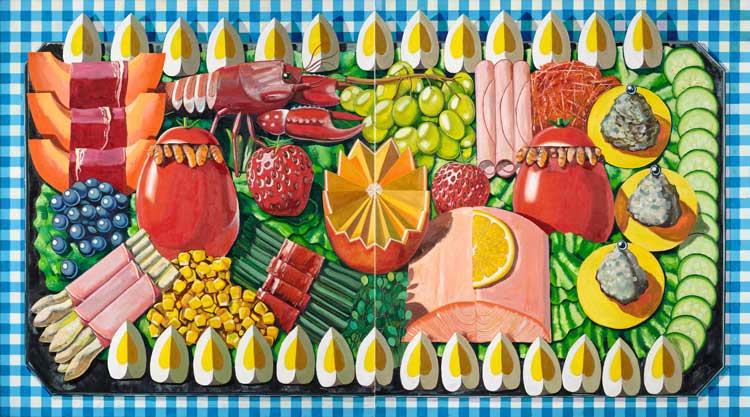

Kristof Santy, Koude schotel, 2024. Oil on canvas, 200 x 360 cm. Courtesy the artist and Sorry We're Closed, Brussels.

Another is that painters today often have a sense of humour. We see a seafood salad blown up to enormous scale (Kristof Santy), a gorilla feeding its child like a Madonna del Latte (Monika Stricker) and uncomfortably close encounters with people slurping up food (Nina Gross). Luís Lázaro Matos’s new commission, Diplomatic Immunity (The Eurorats) (2025), consists of five Jean Cocteau-esque works on canvas, a text painted on the windows and a vast mural reimagining the EU flag as a circle of spermatozoa. This delightfully outrageous installation makes sport with the story of József Szájer, an MEP for Hungary’s anti-LGBTQ+ party Fidesz who was caught fleeing from a “gay orgy” during a Covid lockdown. Matos reimagines him as a rat-man embarking on a journey of emancipation through the Med.

![Vedran Kopljar (& parents), Painting After Painting [34 min 35 sec], 2025. Installation view, Painting After Painting, SMAK, Ghent, 2025. Photo: Dirk Pauwels.](/images/articles/p/&097-painting-after-painting-2025/12.jpg)

Vedran Kopljar (& parents), Painting After Painting [34 min 35 sec], 2025. Installation view, Painting After Painting, SMAK, Ghent, 2025. Photo: Dirk Pauwels.

Several artists mock their own medium’s pretences, particularly in our age of mass reproduction via the smartphone camera. One of the exhibition’s defining works is the mural by Vedran Kopljar (& parents), Painting After Painting [34 min 35 sec] (2025), an uncannily accurate screenshot of a fictitious documentary for the exhibition, complete with dodgy English subtitles. Here we have a painting of an imagined film of a possibly imagined painting, inviting us to photograph it. But the paint’s mottled surface offers us a challenge: do you think you can really replicate this on a screen?