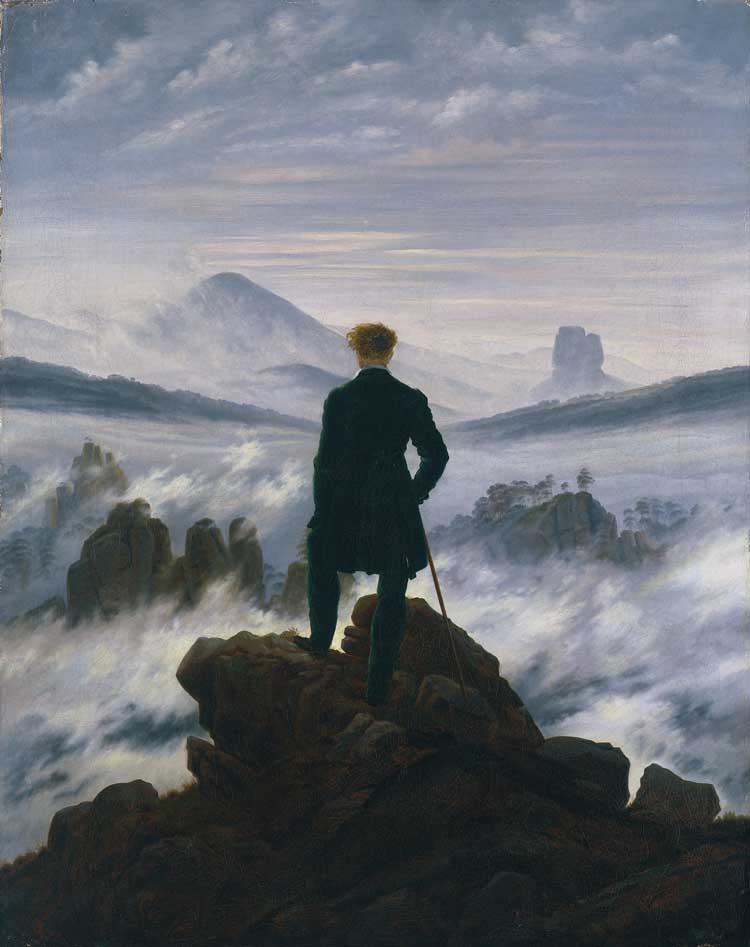

Caspar David Friedrich. Wanderer above the Sea of Fog, ca. 1817. Installation view, Caspar David Friedrich: The Soul of Nature, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 8 February – 11 May 2025. Photo: Richard Lee, Courtesy of The Met.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

8 February – 11 May 2025

by MICHAEL PATRICK HEARN

As far as the public is concerned, there are many one-picture artists. James McNeill Whistler painted his mother, Edvard Munch is known for The Scream. Marcel Duchamp had Nude Descending a Staircase and Andrew Wyeth Christina’s World. If pressed, many people can mention only one Leonardo Da Vinci painting besides The Mona Lisa, the decaying Last Supper. To those outside Germany, the great Romantic Caspar David Friedrich (1774-1840) produced one masterpiece, Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog (c1817). Here, he triumphantly depicted the bold windswept Romantic man, perched precariously on the precipice and yet defying the power and tumult of nature to contemplate the sublime. Gazing into the maelstrom, he will not be defeated by forces beyond his control. He will, by sheer will, tame the vast world about him. Or could he just be deceiving himself? After all, he must now make the dangerous descent of the very mountain he has just so heroically scaled. The Metropolitan Museum has courageously given this long-overlooked artist his first full retrospective in the US. Caspar David Friedrich: The Soul of Nature is a stunning, revelational show. One can never look at this painter’s work in the same light again. He will not be dismissed.

Caspar David Friedrich. Wanderer above the Sea of Fog, ca. 1817. Oil on canvas, 37 3/8 × 29 1/2 in (94.8 × 74.8 cm). Hamburger Kunsthalle, on permanent loan from the Stiftung Hamburger Kunstsammlungen, acquired 1970 (HK-5161). Photo: Elke Walford.

Though a national figure in Germany, he is still little known in the US. This show, brilliantly conceived and mounted to celebrate last year’s 250th anniversary of the artist’s birth, will change that. There have been only two previous shows of Friedrich’s work in the US; they, too, were hung at the Met. The current exhibit is the only one to pull together all five Friedrich paintings held in museums in the US, including the Met’s Two Men Contemplating the Moon, another masterwork of German Romanticism. (Friedrich so liked this composition that he produced three variants: the final one of 1824 included a man and a woman, possibly Friedrich and his wife.) Five only is a shockingly poor percentage out of more than 500 surviving pictures attributed to him. Twelve works by Friedrich’s German Romantic contemporaries bolster the exhibit by providing context and contrast, along with an idea of the artistic circles within which the painter travelled. One key painting is not here: An Idealized Scene of an Arctic Sea, with a Wrecked Ship on the Heaped Masses of Ice (1823-24), now popularly known as The Sea of Ice or The Shipwreck, held by the Hamburger Kunsthalle, Germany. It is said to depict a fatal expedition to the north pole, a place Friedrich never knew. He created the dramatic disturbing painting entirely within his studio from sketches made of the local frozen Elbe. The easy-to-miss shipwreck to the right of the massive shards of ice serves as a commentary on the futility of man to conquer the natural world and nature’s indifference to it all. It is clear that the natural world is eternal while man’s petty concerns are temporal. Also lamentably missing is Mountain Landscape with Rainbow (1809-10) in the Museum Folkwang, Essen, one of the most beautiful of Friedrich’s paintings. A weary traveller pauses to view a thin crescent of rainbow stretched above the mountains despite the dark swirling clouds. It recalls the original covenant of God and Moses after the Flood. Here was the sacred hope for man. It perfectly summarises the artist’s belief in the divinity of nature.

Caspar David Friedrich. Two Men Contemplating the Moon, ca. 1825–30. Oil on canvas, 13 3/4 x 17 1/4 in (34.9 x 43.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Wrightsman Fund, 2000 (2000.51).

Through deft diplomacy, the curators Joanna Sheers Seidenstein and Alison Hokanson have secured important works from throughout Europe, pictures that rarely travel and never abroad. It is unlikely to happen again. Only Russia was left out because of the invasion of Ukraine. With nine of Friedrich’s paintings, the Hermitage in St Petersburg houses the largest collection of the artist’s work outside Germany. The Soul of Nature beautifully unfolds chronologically and thematically. Each gallery is devoted to a different period in Friedrich’s career. Despite the crowds, the Met provides a quiet environment perfect for contemplation. Maru Perez, the exhibition designer, came up with the idea of wall openings that greatly expand the entire space: while passing through one gallery, the viewer can get a glimpse into the next one. It reflects the open windows within many of Friedrich’s pictures. The tones of the walls vary subtly from one gallery to the next, all in various harmonies subdued shades of greyish violet that better bring out the subtle colour of the paintings. It is best to avoid reading the wall captions and allow oneself to be seduced by the inherent force of this transcendental master’s art. Only then consult the handsome catalogue with its stunning reproductions and informed commentary.

Born on 5 September 1774 into a comfortable Lutheran family in the provincial town of Greifswald on the Baltic Sea, then part of Pomerania held by Sweden, this German painted German pictures for other Germans. He fervently believed in a democratically unified Germany. Yet his nationalism seems beside the point today. These are beautiful, inspiring pictures no matter who painted them or where they were painted. While the political landscape changed, the natural world seemed fixed and eternal, largely unaffected by war and other human endeavour. Germany did not become a unified country until 1871, many years after Friedrich’s death. Then three-quarters of a century later it was split again in the aftermath of the nightmare of the second world war. The Nazis did Friedrich’s legacy no favours by embracing his work as epitomising their concept of Blut und Boden (Blood and Soil), in which a racially defined nation was tied specifically to the land. To associate his transcendent work with such a banal and dangerous slogan was unfair: Friedrich was never so blunt nor vulgar. It is embarrassing now to admit that Friedrich was one of the favourite artists of that failed painter Adolf Hitler. Though some of Friedrich’s important paintings were destroyed in the horrendous fire at the Munich Glaspalast museum in 1931, the Third Reich celebrated the centenary of the artist’s death in 1940. Consequently, he fell into disfavour after the war.

The Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog has become the symbol of the German Romantic movement. According to the Anglo-Irish philosopher Edmund Burke in A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful (1757), the sublime “is productive of the strongest emotion which the mind is capable of feeling”. “Dark, uncertain, and confused”, it produces fear for it has the power to attract and destroy. It is all shock and awe before the primal majesty of nature. The wanderer stands boldly, defiantly away from the painter above a bank of turbulent mist. Although Friedrich by no means invented the device, this may well be the most famous example of the Rückenfigur (afigure seen from behind) in western art. He turns his back on order and reason to drink in the sublime. This stance immediately creates a distance between the subject and the viewer; and yet it is unforgettable. It has been imitated and parodied ad nauseam. As with all famous paintings, it remains the steady source for cheap tchotchkes and other touristy souvenirs. It is extraordinary how much kitsch it has inspired. Oddly, the painting was notpopular in its creator’s lifetime and is said to have marked the beginning of the decline in his reputation. Yet Friedrich’s influence can be traced everywhere in popular culture of the 20th century, particularly the movies. Obvious is his influence on the German expressionist films of FW Murnau, particularly Nosferatu (1922) and Faust(1926). Fritz Lang’s masterpiece Metropolis (1927) is no more than German Romanticism gone mad. It depicts a technological dystopia that harnesses nature, leaving nothing of the real world but an artificial pleasure garden at the top of a massive skyscraper. This futuristic fable concludes with the unconvincing, somewhat banal moral: “The mediator between head and hands must be the heart!”

Caspar David Friedrich. The Watzmann, 1824–25. Oil on canvas, 53 1/8 x 66 7/8 in (135 x 170 cm). Nationalgalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin; loaned by Deka, Frankfurt am Main (F.V. 317). Photo: © DeA Picture Library / Art Resource, NY.

Likewise, Friedrich’s German mountain paintings of the 19th century led to the German mountain movies of Leni Riefenstahl in the 20th. Even the peak above the clouds in Paramount Pictures’ logo bears more than a hint of Friedrich’s The Watzmann. Stuart Jeffries in the Guardian last year explored the possibilities of Walt Disney’s fondness for Friedrich’s primeval forests in the settings for the animated feature Bambi (1942). Friedrich even has a place as a footnote in modern literary history: the playwright Samuel Beckett admitted that the germ for Waiting for Godot (1953) came from his observation of “pleasant predilection for two tiny languid men in his landscapes” while viewing a display of Friedrich’s paintings in Dresden in 1937, in particular one of the versions of Two Men Contemplating the Moon. The painter’s life and art became the subject of the 1986 German biopic Caspar David Friedrich – Grenzen der Zeit, (Boundaries of Time: Caspar David Friedrich). This handsome, ambitious award-winner maintains the old Hollywood cliche of the artist as a stubborn misunderstood genius who cannot be fully appreciated until after his death. It supplies a posthumous reflection on the painter’s lasting achievement: Friedrich does not appear in the movie, but he is heard in the voiceover.

Friedrich studied at the University of Greifswald and later the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen for four years before settling in Dresden where he married, raised a family and remained for the rest of his life. It was from here that he drew most of his inspiration. He boldly chose not to pursue his studies in Italy as was expected of artists at the time. Friedrich did not have to make a pilgrimage to Rome or Paris in pursuit of beauty. All he had to do was look out of his window to find it in the German countryside. Friedrich’s art fully exploited the passion for mountain climbing. Traipsing through the verdant unspoiled forests and mountains of Europe displaced the Grand Tour. These happy wanderers passed through areas that were not yet tourist traps. Consequently, Friedrich’s art is often refreshingly free of any mark of civilisation. While other artists visited distant lands in search of unexpected locales for their paintings, Friedrich remained true to his own backyard. There is nothing exotic about his art. Critics have long pointed to the deep melancholia that imbues many of his works. He lost his mother, his sister and then his brother while a boy; and these losses may have influenced his lifelong misanthropy. Friedrich redefined the long-held western concept of landscape painting. His contemporary, the French sculptor David d’Angers, credited Friedrich with having “created a new genre: the tragedy of the landscape”. A master of sunrise and sunset and moonlight, of fog and frost, he dealt as much with atmosphere as with the physicality of landscape. He was often content to depict grim, spent tree trunks and stumps and stones in winter in meticulous detail. Yet there is nothing inherently noble about such sombre pictures.

Caspar David Friedrich. The Evening Star, ca. 1830. Oil on canvas, 13 x 17 13/16 in (33 x 45.2 cm). Freies Deutsches Hochstift, Frankfurter Goethe Museum,

Frankfurt am Main (IV-1950-007). Photo: © Freies Deutsches Hochstift / Frankfurter Goethe-Museum. Photo: David Hall.

Dresden at the time was a thriving artistic capital, an important supporter of landscape painting. Friedrich stood at the centre of a lively circle of fellow artists and students. Exploring nature served as an act of self-discovery. It supplied a safe space for the soul. Friedrich enjoyed hiking with other painters; and he visited spas to restore his health later in life. He won a painting contest in 1805, one of the judges of whom was the German writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. Friedrich defied the competition’s requirement to depict an event from the myth of Hercules. Instead, he submitted two contemporary bucolic scenes in summer, including one of a pilgrimage to a sacred site in some long-lost religious ritual. He won anyway. Goethe did visit Friedrich’s studio, but the two eventually had a falling out. In 1810, Friedrich was elected to the Berlin Academy after the Prussian Crown Prince bought two of his paintings. The future Tsar Nicholas I of Russia and his German-born wife Charlotte likewise adored Friedrich’s art; Nicholas visited the Dresden studio in 1820 when still a duke and returned to St Petersburg with several pictures. He later added others to his collection.

The Napoleonic wars completely reconfigured Europe. French oppression awakened new nationalities, new borders, new countries. Germany at the time was just a collection of disparate and still feudal principalities loosely held together by language, culture and history. The conquerors vainly tried to force neoclassicism on the conquered populace. German Romanticism arose in defiance of French cultural imperialism. These sons of Martin Luther refused to take orders from Roman Catholic France. German writers and artists now looked back to their own traditions and themes to define a native German mythology free of foreign cultural influence. They turned from Ulysses, Orpheus and Helen of Troy to Siegfried, Faust and Snow White. Out of this Romantic fervour, the Brothers Grimm not only started to compile the first comprehensive German dictionary (left unfinished at their deaths), but also collected Volksmärchen, the true spoken folk literature, directly from the lips of the German people. Friedrich knew the tyranny firsthand when invading troops occupied Dresden from 1812 to 1813. Yet none of the devastation caused by the French in and around the city shows up in his paintings. Two Men Contemplating the Moon was an overt act of protest: Friedrich subversively decked the figures in black velvet caps and capes, Altdeutsche (Old German) garb of the 1500s and 1600s, the time of Luther, that student rebels had adopted to honour their former national greatness. He put a solitary lonely French Dragoon in The Chasseur in the Forest (1813-14), parted from his regiment, either lost or trying in vain to find his way home among the majestic German evergreens, the traditional symbol of Christ. The oppressive Carlsbad Decrees of 1819 introduced conservative ideological censorship that dragged Friedrich into court, accused of making antimonarchist statements.

The Age of Reason had given way to the Age of Feeling, to a new intensity of expression. The Enlightenment favoured intellectual detachment while Romanticism and the earlier Sturm und Drang movement embraced the intense emotion of the individual. The artist had to explore his inner life. Originality, inspiration, and imagination were all things the earlier age distrusted, if not detested. The individual was now more valued than society, passion was more important than the intellect. Beauty and aestheticism were considered superior to order and reason. The imagination replaced the intellect. The will of the individual was paramount. Originality was the key. What was depicted was not as important as how it was done, how it reflected the artist’s unique personality. Friedrich said as much: “The artist should paint not only what he sees before him, but also what he sees within him. If, however, he sees nothing within him, then he should also refrain from painting that which he sees before him. Otherwise, his pictures will be like those folding screens behind which one expects to find only the sick or the dead.” Inspiration was key to Friedrich’s lofty approach to landscape painting. He believed that the noblest aim of the artist was “to stimulate the spirit and arouse thoughts, feelings and sensations in the viewer, even if there are not his own”.

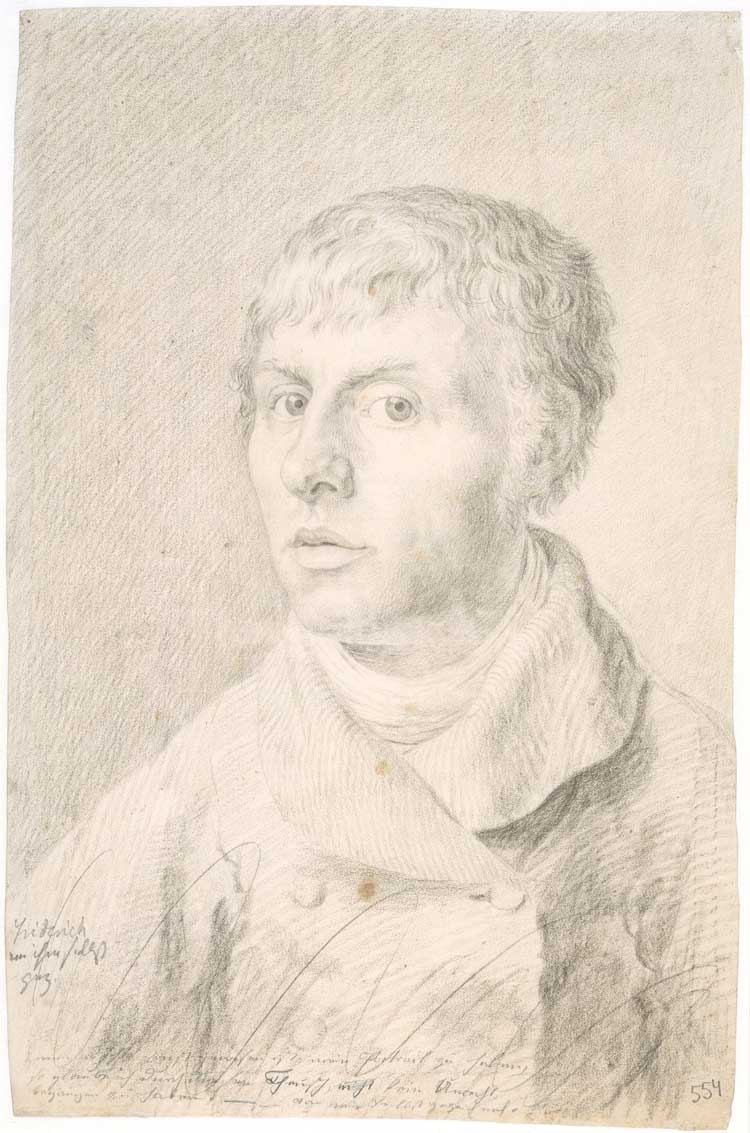

Caspar David Friedrich. Self-Portrait, 1800. Black chalk on wove paper, 16 9/16 x 10 7/8 in (42 x 27.6 cm). SMK, National Gallery of Denmark, Copenhagen (KKSgb5006). Photo: Statens Museum for Kunst.

In spite of the intense, brooding self-portrait in fine black chalk of 1800 that opens the show, The Soul of Nature is not about faces. Figures do appear within the natural world in some of the earliest drawings, but portraiture never much interested Friedrich. Most of his people are shown from the back. There are four extraordinary virtuosic woodcuts from 1803, including a rigid self-portrait, that may all have been intended as illustrations for an unrealised collection of Romantic poems. The artist must have drawn directly on the woodblocks, and his brother Christian Friedrich then cut them. Their line has the authority, bite, weight and precision of Albrecht Dürer’s more celebrated Renaissance prints. They are fraught with traditional morbid symbols. The spider’s web spun between two spent trees reflect the girl’s entangled personal life. A raven perched on a barren branch serves as a possible portent of a loved one’s impending death or even the young woman’s demise. While a boy sleeps on an overgrown grave, the soul of the deceased can be seen as a butterfly (or is it a moth?) hovering above his head. It is a shame the artist did not further explore this form.

Caspar David Friedrich. Castle Ruins at Teplitz, 1828. Watercolour over pencil on wove paper, 6 13/16 x 9 ¼ in (17.3 x 23.4 cm). Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden (C 1913-33). Photo: © Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche

Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Photo Herbert Boswank.

Friedrich pursued a new spiritual approach to painting. Like his fellow patriots, Friedrich sought references to the lost German past, to the last remnants of the glory of the middle ages, a now forgotten golden age of German culture. He abandoned temples with broken Roman columns of the French and Italian tradition in favour of the ruins of ancient gothic churches, castles and other edifices where the land reclaimed what man once wrought. Friedrich did not dress his sylvan glades with cavorting aristocrats and classical figures as had the French artists Antoine Watteau, Nicolas Poussin and Claude Lorrain. He did not clutter up his compositions with obscure biblical or mythological or historical references. His pictures are not the idealised dreams of lost Arcadia. Friedrich’s are free of the froufrou prettiness of the formal gardens of Jean-Honoré Fragonard and François Boucher where sexual seduction was their primary end. Before Friedrich, landscape provided little more than a setting for a dramatic event in history or literature. Friedrich, in contrast, depicted modern German men and women communing with the majestic virgin landscape. It was highly liberating for the painter to be unfettered by any mythological, literary or historic context. He found a still, solemn holiness there. Art had long been considered the result of divine inspiration. Painting by its very nature was a sacred act. German towns were still largely medieval, surrounded by preindustrial farms and untouched forests. His skies are free of pollution, the dark smoke that the English critic John Ruskin dubbed the “plague cloud”, which he said changed for ever the very nature of landscape painting in the latter 19th century. No steam engines or factories befoul Friedrich’s clear, clean skies, no trains rattle through the countryside. There are no steamships in his harbours, only mighty sailing craft.

Caspar David Friedrich. Moonrise by the Sea, ca. 1835–37. Brown ink and wash with pencil on wove paper, 10 1/8 x 15 1/8 in (25.6 x 38.5 cm). Kupferstichkabinett, Hamburger Kunsthalle (1952-131). Photo: bpk Bildagentur / Kupferstichkabinett, Hamburger Kunsthalle / Art Resource, NY.

Until the Romantic age, landscape had often been treated as a minor art, as background only, as merely scenery for a religious or historic scene. Friedrich put down wide stretches of countryside with not even one lonesome building to break up these vast vistas. Man appears to have no business being here. This seemed to be something new in landscape painting. Friedrich replaced the lowly flatlands of Netherlandish art with the majesty of mountains. By contrast, Dutch landscapes and seascapes were flooded with brightest sunlight while Friedrich concentrated on capturing moodier sunrise, sunset and moonlight as the true expression of the artistic self. Friedrich seemed to portray landscape for its own sake, but that was all a beautiful deception. His paintings were idealised constructs. Unlike the impressionists who worked en plein air, Friedrich did not paint directly from nature. “A picture must not be invented but felt,” he insisted. In his world of shadow and fog, his landscapes are not actual places. They are often pastiches of various elements he brought into the studio. He would compose a scene from sketches he had made outdoors and then meticulously render on canvas as if it were real. As noted by the Met curator Sabine Rewald in Moonwatchers, her 2001 book on Friedrich, he readily elevated ordinary subjects by employing what the Romantic poet Novalis called the “estrangement effect”, which gave “the commonplace higher meaning – the familiar an enigmatic look, the finite the appearance of the infinite”. His masterful drawings of plant and rock were only the means to another end. He painted every leaf and rock with Dürer-like precision, a method that anticipates the English pre-Raphaelites and their rendering of the visible world bathed with spiritual truth.

Raised a devout Lutheran in an era of widespread religious scepticism, Friedrich embraced the new gospel of nature. He viewed the natural world as a reflection of the Lord’s all-embracing creation. The German theologian and poet Ludwig Gotthard Kosegarten profoundly inspired the young painter to look to the natural world as Christ’s Bible. Christian iconography is everywhere in these early works with crucifixions and Madonnas sprouting on the mountains and in the forests of Friedrich’s sacred wilderness as a reminder of God’s good grace. Nature acts as a reflection of the divine world order that man watches, contemplates and feels rather than thinks and calculates. The Cross in the Mountains, also known as the Tetschen Altar (1807) (that has not travelled to the Met), with its overly ornate gold-leaf frame by Christian Gottlieb Kühn, is an altarpiece for this new faith. The crucifix, bathed in otherworldly light, towers above the firs on the mountaintop, as if by some divine intervention. Commissioned for a private chapel, the picture was shocking when it was first exhibited in 1808. It lacked any traditional perspective; and some people absurdly considered it blasphemous. It must have suggested to some a new kind of paganism. Frederick’s natural altarpiece paid homage as much to the emerging religion of nature as to the original crucifixion. It fused the sacred with the profane. He defended the composition by saying it was an act of sincere belief: “The Cross is raised high on the rock, solid and immutable, like our faith in Jesus Christ. And everlastingly green, for all time, the firs encircle the cross, like our hope in Him, the Crucified.” His was a humble Christianity. He found nobility within simple rustic life. Like Martin Luther before him, he saw more beauty in God’s creation than in all the mighty cathedrals of Christendom. Nature is the Lord’s cathedral.

Caspar David Friedrich. View of Arkona with Rising Moon, 1805–6. Brown ink and wash, over pencil, on wove paper, 24 x 39 3/8 in (60.9 x 100 cm). The Albertina Museum, Vienna (17298).

The unearthly glow that bathes the decaying yet still sturdy arches of the gothic church in Ruins at Oybin (c1812) looks forward to the intense light captured so beautifully by later painters such as the American Frederic E Church of the Hudson River School. The shapes of the three empty windows form slim golden silhouettes that suggest saints or angels. This monastery in its abandoned state has been reclaimed by nature, the new religion of the German Romantics. They adored the rebelliousness of the natural world. These poets and painters revered the ruins of German life, culture and religion. These young idealists read nature as an open book of God’s goodness and abundant grace. The divine could be revealed in mountains and seas as easily and profoundly as by God’s other messengers, the angels, prophets and saints. Painting God’s vast creation was by its very nature an act of the divine.

The German Romantic poet and playwright Heinrich von Kleist called the ethereal Monk by the Sea (1808-10) “a miraculous painting” and beholding it “is as if one’s eyelids had been cut off”. “If you were to meditate from morning to evening, from evening to deepening midnight,” Friedrich warned in regard to this work: “You would never comprehend, never fathom the unknowable hereafter! With bold presumption, you think you can become a light to future generations, can decipher the darkness of the future! Which is only ever sacred intuition, to be seen and recognised only in belief; to know clearly and to understand at last.” The picture invokes the vast looming emptiness of the infinite. In a companion piece not in this show, The Abbey in the Oakwood (1809-10), monks carry a coffin of one of their own to be buried within the hallowed hollow of their ruined monastery. This ritual may be seen as one of the last vestiges of the once mighty Catholic faith. Friedrich intended this painting “to represent the mystery of the grave and the future”. Friedrich’s art reflected the obsession with death and tombs and the ruins of Germany’s gothic past, the last vestiges of the once mighty Holy Roman Empire. Dying was everywhere in Romanticism, perhaps most notably in the suicide of Goethe’s Young Werther over a broken heart and Von Kleist’s murder and suicide with his young lover. In the US, Edgar Allan Poe declared the finest subject for poetry to be the death of a beautiful woman. These languid lovesick lachrymose young men with their intensity of feeling were the true fathers of modern emo.

Caspar David Friedrich. Monk by the Sea, 1808–10. Oil on canvas, 43 5/16 x 67 ½ in (110 x 171.5 cm). Nationalgalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (NG 9/85). Photo: bpk Bildagentur / Nationalgalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin / Andres Kilger / Art Resource, NY.

If not for that tiny solitary figure, identified as a monk, standing on a mere silver sliver of shore, the minimalist Monk by the Sea would just be a study in harmonious brooding colour rather than a sardonic visual comment on the unknowable. The painter offers the slimmest glimmer of hope with the emerging blue sky above the waning storm clouds. Shrunk by his swirling surroundings, the man stands boldly like Shakespeare’s Prospero, surveying alone his brave new world. It also calls to mind the Swiss symbolist Arnold Böcklin’s Island of the Dead (1883-86). Originally, Friedrich drew three ships in the harbour with every sail and spar fastidiously rendered. Then he painted over them. He left only vast expanses of flat colour in a composition that is not that far removed from Whistler’s later symphonies in silver and grey, blue or green. Those four luminous stripes of sea, shore and sky look forward to Mark Rothko’s Green on Blue (Earth-Green and White) (1956) as Hokanson points out in her essay Friedrich in the United States in the Met’s sumptuous catalogue accompanying the show.

Friedrich’s religious fervour appeared to wane with the end of war with France in 1815 and his landscapes reflected a renewed spirituality free from crucifixes and spent monasteries. Yet, in their truest sense, all his landscapes are religious even without the obvious Christian symbols, all those mountain and roadside crosses, in the early paintings. They keenly express the power and the glory of God in Nature. At times, these pictures are as much political as religious. Critics marvelled not only at the technical virtuosity of his landscapes, but also the mood he evoked free of any direct human context. It was an entirely new way of depicting nature, seemingly liberated from the human presence. Turning his back on the Industrial Revolution, with his cool, clear precise inner eye, Friedrich examined raw landscape, untouched by man. His paintings are often not of actual places, but imaginary idealised ones invented in the studio from various elements taken from different on-site sketches. He advised the young painter to close the bodily eye so one could see with the spiritual one. “The artist’s task is not the faithful representation of air, water, rocks and trees, but rather his soul, his sensations should be reflected in them,” he argued around 1830. “The task of a work of art is to recognise the spirit of nature and, with one’s whole heart and intention, to saturate oneself with it and absorb it and give it back again in the form of a picture.”

His pictures went beyond mere observation. He learned to paint with his inner eye, the vision of the soul. The Watzmann (1824-25) depicts one of the most beautiful and easily recognised of the Berchtesgaden Alps in Germany, yet Friedrich never saw it. Instead, he based his composition on sketches made by a student who had journeyed there. Friedrich created a wholly believable fantasy landscape of picture postcard perfection, Nature as the image of the divine where Heaven and Earth meet. Here again, he depicted the timeless, virginal grandeur of natural formations untouched by humans. Not even a vagrant hut ties it to man’s presence.

Caspar David Friedrich. Moonrise over the Sea, 1822. Oil on canvas, 21 5/8 x 28 in (55 x 71 cm). Nationalgalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (W.S. 53). Photo: bpk Bildagentur /Nationalgalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin /Jörg P. Anders / Art Resource, NY.

Friedrich never fully mastered the human form divine. There are no nudes in the Met’s retrospective. Like his English contemporary JMW Turner, Friedrich was primarily an atmospheric painter. Yet each rendered sky and sea and shore in his own unique way. Their compositions lack the formal geometric symmetry so typical of previous western art and neoclassicism in particular. While Turner tried to tame turbulence within a moment of time, Friedrich often explored tranquillity. The naked body held little attraction for either man. Anatomy and physiognomy bore no glamour for them. Their figures are at times quite clumsily rendered. People are put in these scenes merely to indicate scale. They are generally overwhelmed by their vast environment, natural man shown vulnerable to the natural world. While his vision may have been clear, the hand of the artist was largely invisible in Friedrich’s work unlike that of Turner and their successors, the impressionists, where the brushstroke itself defined a painting more than did its subject.

Friedrich and his family lived a largely solitary, spartan life. Contemporaries referred to him as a “mystic with a brush”. This reclusive “monk-like mystic” (as another described him) diligently worked within his nearly empty studio with the windows shuttered to avoid any distractions to his inner vision. His friend Georg Friedrich Kersting’s handsome 1819 portrait of Friedrich painting captured the intensity of the artist at work in that sparse space. Although he did not paint nudes, he was known to paint in the nude. He believed in completeness of the self, unfettered by societal constraints or expectations.

Perhaps the closest to the erotic he ever came was Woman at the Window (1822), another Rückenfigur, but one of only three known interior scenes. The artist tenderly painted his young wife as she peered from the artist’s studio to greet the bright new day. He had married Caroline, a woman nearly 20 years his junior, in 1818, the same year he joined the Saxon Academy; and theirs seems to have been a happy union. They had several children, three of whom reached adulthood. As Caroline is seen from behind, one can only imagine her reaction to the morning light and the passing ship on the Elbe. One can nearly trace her form beneath the diaphanous dress. Friedrich may have initially painted her naked body and then covered it. It is a tender affectionate semi-portrait of his beloved. He fondly renders the contours of the bump of her plump rump as it is softly caressed by the folds of the skirt. Could she at the time have been pregnant with their second daughter? Is that a maternity dress she is wearing? That may explain why its waist is unusually high: she may be just beginning to show. Friedrich knew this picture was special: it remained in the family for decades after his death.

The severe geometry of that dark austere room contrasts beautifully with the bright delicate details of the living world outside. Its tranquillity aches with longing. The picture inspired the German Romantic poet Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué to compose a sonnet, in which he pleaded: “Oh no no, benevolent mystery, / do not turn your face to me! / Leave me silent, trembling in soulful anticipation.” It is reminiscent of Greta Garbo asking the director Rouben Mamoulian what she should do for the final, lingering closeup in Queen Christina (1933) at the bow of the ship after her lover has been killed and she heads into exile. He replied: “Nothing … You don’t have a thought … Just wear a mask.” The audience would provide her thoughts.

Caspar David Friedrich. Woman before the Rising or Setting Sun, ca. 1818–24. Oil on canvas, 8 5/8 x 12 in (22 x 30.5 cm). Museum Folkwang, Essen (G 45). Photo: Museum Folkwang Essen - ARTOTHEK.

The corniest composition in the entire exhibit is Woman before the Rising or Setting Sun (c1818-24). Dawn and dusk are interchangeable within Friedrich’s world. He produces a heightening intensity as one moment transitions into the next from daylight to sunset or moonlight to morning. There is no grace in the oversized female figure, again his wife, a German giantess pressed against the theatre curtain of a landscape.

Caspar David Friedrich. The Stages of Life, ca. 1834. Oil on canvas, 28 ¾ x 37 in (73 x 94 cm). Museum der bildenden Künste Leipzig (G 1217). Photo: bpk Bildagentur /Museum der Bildenden Künste, Leipzig / Bertram Kober/ Punctum Leipzig / Art Resource, NY.

Perhaps the most disappointing work in the show is the oddly named seascape The Stages of Life (c1834), a meditation on mortality. This enormous canvas has none of the precision of his earlier pictures. The figures in the foreground may represent several generations, but they are awkwardly painted, lacking the authority of younger work. The dark ships of this terrible picture seem pasted on to the moonlit sky. They do not sit on that sea. They pop right out of the picture space. Friedrich has lost all sense of perspective. Even the evening sky lacks the intensity and luminosity of colour so typical of this artist’s haunting art. An exceptional painting, however, is the late Neubrandenburg on Fire (c1834) for it was left incomplete. It is a companion to Neubrandenburg or Neubrandenburg in the Morning Mist of 1816-17, both depicting his parents’ hometown. The lack of finish in the later picture reveals exactly how the artist worked. One can almost see him thinking as he carefully builds up the forms with thinly painted layers of colour over precise pencil drawing on canvas. It is another ambiguous painting: no such fire took place in Friedrich’s lifetime. Is the sun rising or setting? Does it offer the glimmer of hope, or does it merely mark the destruction of civilisation? Is the artist approaching or retreating from the conflagration? One guess is as good as another.

Caspar David Friedrich. Cave in the Harz, ca. 1837. Brown ink and wash with pencil on wove paper, 13 9/16 x 17 3/16 in (34.5 x 43.7 cm). The Royal Danish Collection, Copenhagen (I, 3 a-3). Photo: HM The King's Reference Library, The Royal Danish Collection.

Friedrich was at the height of his reputation in June 1835 when he suffered the first of a series of strokes that, over the next five years, would scuttle his career. His later years were marked by violent mood swings and uncontrollable rages. His inherent melancholy produced murky minimalist monochromatic pictures of graveyards guarded by owl or vulture. These meticulous studies of sand and stone are just depressing. Empty of any human contact that might determine their period, his studies of stone and cave and rocky shore appear timeless, of any and all periods, almost prehistoric. It is no surprise, therefore, to learn that his career suffered a steady decline along with his failing health and inspiration. The fickle art world had moved on. His career waned as the public replaced the mundane with the exotic. It was an age of wide exploration, conquest and colonisation; and the folks back home wanted to see what lay beyond in far off lands. This shift in taste left Friedrich in abject poverty. In 1837, he had another stroke, leaving him almost completely paralysed and he never returned to painting. He died in Dresden on 7 May 1840 at 65, forgotten.

Friedrich was rediscovered in 1906 when 36 paintings and 57 drawings were included in the Centenary Exhibition of German Art 1775-1875 in Berlin. He was the star of the show. Then Hitler’s horrible admiration for the work all but destroyed his reputation. Friedrich’s personal nationalism now became suspect. The British art historian Kenneth Clark dismissed him in 1949 for working “in the frigid technique of his time, which could hardly inspire a school of modern painting”. Nevertheless, in the intervening years, Friedrich has profoundly influenced modern culture in unexpected ways. Other critics have pointed out affinities between his work and that of such differing painters as Albert Pinkham Ryder, Munch, Edward Hopper, Wyeth, Max Ernst, René Magritte, Gerhard Richter and Anselm Kiefer, among others. The Tate Gallery in London held an important exhibition of Friedrich’s work in 1972. Two years later, the Hamburger Kunsthalle finally restored him as a major painter of international significance with a bicentennial exhibition. The 250th anniversary of his birth has been met around the world with important retrospectives, culminating with the Met’s magnificent exhibition.