Charlotte Johannesson, Untitled, 1981–85, installation view, Radical Software: Women, Art & Computing 1960–1991, Kunsthalle Wien 2025. Courtesy the artist, Hollybush Gardens, London, and Croy Nielsen, Vienna. Photo: kunst-dokumentation.com

Kunsthalle Wien, Vienna

28 February – 25 May 2025

by MAX L FELDMAN

Curators can learn a lot from Radical Software. It not only tells us about the history of digital art but makes us think about something that gets talked about a lot without being much understood: the speed with which our perceptual habits have changed in the last five decades, let alone centuries. Despite the exhibition’s size – it displays no less than 50 female computer artists across Kunsthalle Wien’s two floors – we are encouraged to feel a sense of productive alienation from our own ways of seeing. Looking at decades-old works made with often long-obsolete technology can help us peer into what Susan Sontag called the “grammar and ethics of seeing” – how, after photography, the way in which we see the world and make judgments about what we see has been structured by image-making technologies.

This effect hinges on two intertwined issues. The focus on femalecomputer artists – until recently, victims of a gendered and medium-based exclusion from art history – sharpens our sense of the political stakes. This can be pushed further if we reconsider another familiar idea that is often misinterpreted: Marshall McLuhan’s distinction between “hot” and “cool” media.

For McLuhan, “hot” media (eg radio) flood a single sense with data: they provide lots of information but need little audience participation. “Cool” media (eg television), on the other hand, ask more of multiple senses, thus inviting participation. This is often misunderstood. It is rarely pointed out that the distinction isn’t absolute. A medium is, rather, relatively hot or cool depending on its relationship to others available at any one place and time, including successive generations of products and obsolete forms. This is especially relevant when considering computer art, since the accelerating rate of change – which is what the feeling of being “modern” and making and seeing modern art is all about – can be very clearly seen and experienced in the case of computers. Making younger generations more aware of this won’t slow anything down, but historicising our own recent experiences may be useful in guarding us from the vertigo of the endless present.

Installation view, Radical Software: Women, Art & Computing 1960–1991, from left to right: Miriam Schapiro, The Palace at 3:00 AM or Meander, 1971, courtesy the artist and Eric Firestone Gallery; Sonya Rapoport, Shoe-Field installation, 1983–89, courtesy Estate of Sonya Rapoport, Kunsthalle Wien 2025. Photo: kunst-dokumentation.com © Bildrecht, Wien 2025.

Radical Software places Miriam Schapiro’s The Palace at 3.00AM or Meander (1971) in the same space as Joan Truckenbrod’s Congealing Weaves and Energy Surface (both 1981). They almost look familiar without it being easy to remember where and when we have seen these kinds of images before, certainly without them being part of post-internet parodies. Schapiro’s work is a series of purplish intersecting cuboids with yellowish shading that looks like a primitive digital labyrinth; Truckenbrod’s works, with their vaguely new age titles and effects, consist of waves of coloured patterns and stars – dark turquoise and lilac in the former, magenta and violet in the latter.

Decades later, these images certainly feel dated, but getting to grips with the ageing of what was once very new is the first move we must make if we are to feel anything about them. Only then can we shift gear and consider what they look like and how they were made, which are essentially opposites. The Palace is a “computer painting”, which Schapiro made by drawing a shape by hand and turning it into code that could be manipulated by custom-built software – the venerable tradition of draughtsmanship uploaded to the computer Truckenbrod’s works were, by contrast, produced by photographing the code from the computer screen and printing it on to textile, transferring data from the computer to the venerable traditions of craft production.

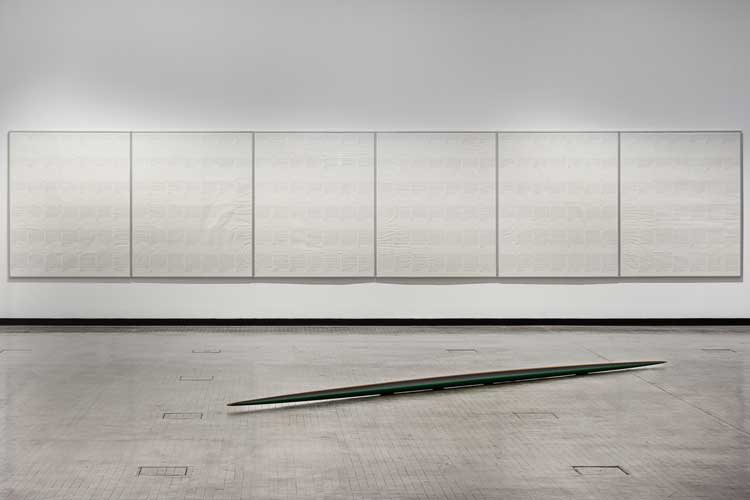

Installation view, Radical Software: Women, Art & Computing 1960–1991: Hanne Darboven, Ein Jahrhundert-ABC, 1970–71, courtesy the artist and Sprüth Magers; Isa Genzken, Untitled, c1976–77, courtesy the artist and Galerie Buchholz, Berlin; Kunsthalle Wien 2025. Photo: kunst-dokumentation.com © Bildrecht, Wien 2025.

Neither of the artists’ work is entirely hot or cool in McLuhan’s sense: they invite discussion – other types of participation with the medium of painting are rare – because the methods the artists used to make them need to be explained to the public, but the demands they make on how the viewer perceives them differ in hotness or coolness, depending on their expectations about what artists can achieve using computers and how it compares with consumer technology they can use themselves in their (monetised) leisure time. They provide some insight into how the gaze has been shaped by successive technological leaps, the speed of which has made it hard to assess the changes themselves and what they have done to the act of looking. And they do so while representing the middle of the period under consideration in the exhibition.

Lest we forget, in the early 1960s, computers were vast whirring monsters. They took up whole rooms, like the mechanical looms in textile factories half-a-century earlier or more – evoked in the Truckenbrod pieces as well as Beryl Korot’s Text and Commentary (1976-77), which juxtaposes tapestries with videos of the process of their production and the artist’s sketches – and could be found only in large companies or computer science departments in well-endowed universities or big cities, for example.

Among the earliest works in this show are two pieces by Inge Borchardt, both called Untitled (Serie A) (1966). Their arcing ovals look like Renaissance-era astronomical diagrams reimagined in the clinical language of code, only these are solar systems without planets, their celestial bodies replaced by printed lines representing movements with no origin or end.

Installation view, Radical Software: Women, Art & Computing 1960–1991, Kunsthalle Wien 2025. Photo: kunst-dokumentation.com

This was, interestingly, the year in which US President Lyndon Johnson signed the Freedom of Information Act into law with the intention of increasing government transparency. This piece of legislation had little if anything to do with the Poem Drop event (1971), at least not directly. Organised by Alison Knowles, for this performance the artist used a helicopter to distribute paper copies of her computer-generated poem The House of Dust (1967) over a collective living space at California Institute of the Arts.

None of this refers to FOIA, or any other policies, Johnson-era or otherwise. There is, however, no doubting that this piece has an activist tone – the drama given by the helicopter, the printed sheets of paper flapping in the wind like loose bits of a manifesto – that can’t help but recall the long-lost atmosphere of the times. This also suggests thatthe artistic use of computers cannot be separated from the social and political context in which they are used, something emphasised throughout the exhibition and its catalogue.

Hence Katalin Ladik’s 11-piece series Genesis (1975), a series of gelatin silver prints showing circuits from the insides of radios, computers and televisions. The circuits were meant to produce sound as a way of reflecting on how quickly technologies become obsolete. No doubt someone with an engineer’s eye could tell us what they were without looking at the labels. To the layperson, however, they appear as the mute innards of nameless machines, looking like reflections on how to release the democratic potential of technology trapped inside those circuits, just as the photo documentation of Knowles’s event looks like an act of guerrilla open access, even if that isn’t entirely what was intended.

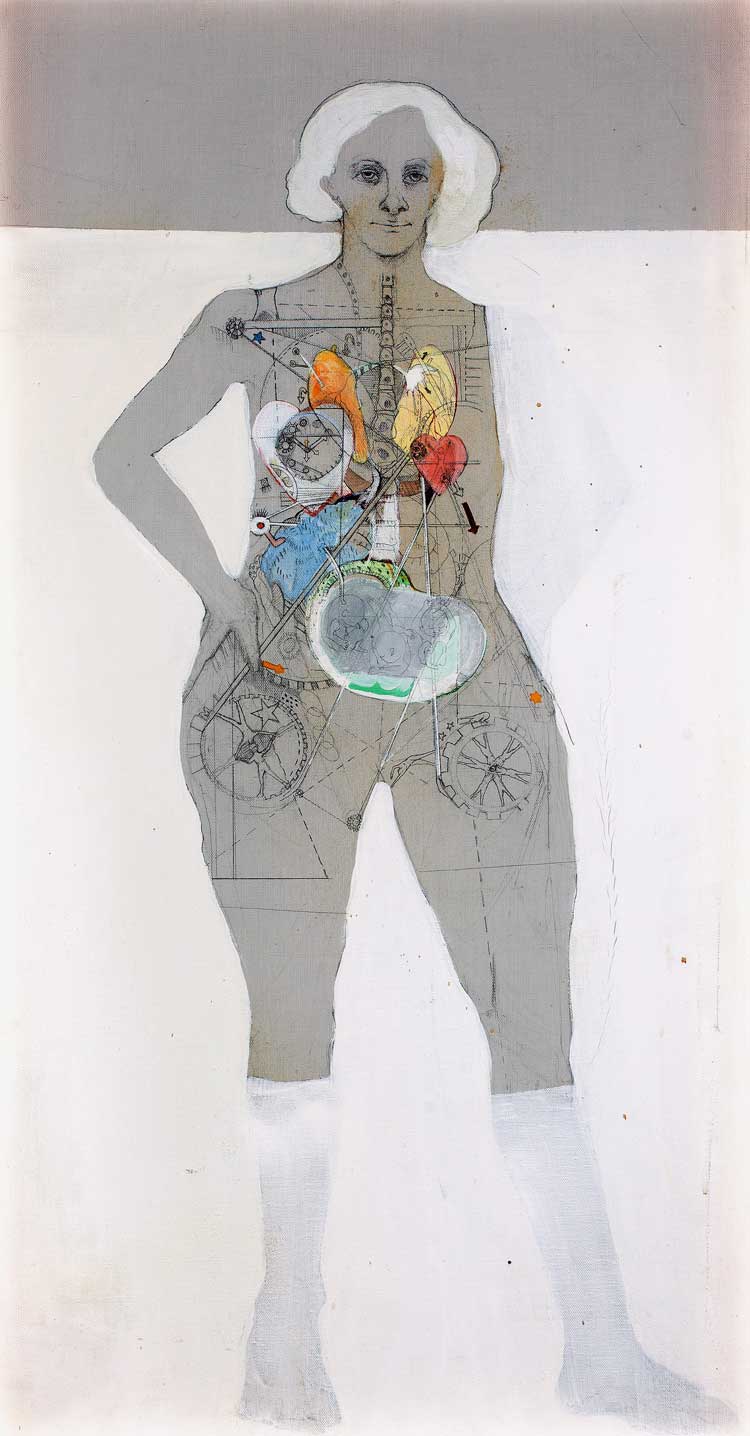

Lynn Hershman Leeson, X-Ray Woman, 1966. Collection Hartwig Art Foundation, promised gift to the Rijksdienst voor het Cultureel Erfgoed / Rijkscollectie.

Whether either artist expected any government – American democracy in the case of Knowles, Yugoslav state socialism in Ladik’s – to make good on that potential matters less than how they were made at the same time as public trust in institutions began to crumble just about everywhere, a situation with lessons to tell us about how we respond to the comfortable relationship between the private owners of technology firms and political power today.

The year 1966 is also when Joseph Weizenbaum, an associate professor at MIT’s Artificial Intelligence Laboratory, wrote Eliza, a computer psychotherapy program, one of the first programs to introduce artificial intelligence to the public. Eliza encouraged users to type their deepest sorrows into the computer, which would respond with an air of generic supportiveness based on linguistic prompts, most of which were cliches. Someone sitting at the computer would type in messages explaining how sad and alone they felt, and Eliza would express sympathy and ask for further details, prompting the user to divulge ever more in a positive feedback loop of human-machine intimacy.

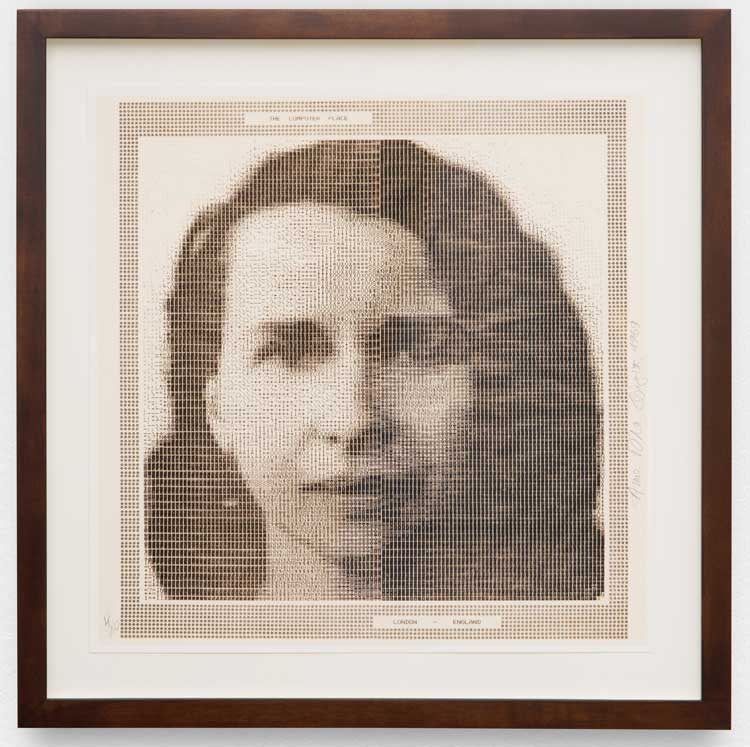

Anna Bella Geiger, Self-Portrait, 1969. Courtesy the artist and Mendes Wood DM, São Paulo, Brussels, Paris, New York. Photo: Pauline Assathiany.

Hence the emotional crux of Radical Software: Anna Bella Geiger’s Self-Portrait (1969). The calculated tenderness first seen in Eliza reappears here in what is typically meant to be the most intimate medium of all, the one that really involves the artist looking at themselves and unsparingly showing this to the world. If Eliza frustrates the hot/cool media distinction because the individual is fully engrossed in the activity, this becomes even more intense in the case of the human face, which demands several different forms of deep attention at the same time if people are going to respond to one another sufficiently,. This sense of responsibility isn’t diminished if the face, like Geiger’s, is only rendered in lines and dots on yellowing paper, it’s simply presented with new ethical and political challenges, giving new shading to the problem of the grammar and ethics of seeing. Here, the artist’s face cannot be seen as an expressive whole because a full clear view is interrupted by what printers were able to do at the time; the shadows naturally cast by falling light become murky blurs, deepening a haunting feeling that comes with all self-portraits, even when it isn’t intended.

In the last years covered by Radical Software, computers were more familiar, and will certainly seem so to any viewers who had access to personal computers and associated technologies from a young age. By this point, tertiary sector employees in developed economies used computers every day of their working lives; younger people played video games attached to televisions, causing a moral panic that is still with us today in heightened and better-justified form; easy-to-use personal computers would soon become available in people’s homes, making it possible for to optimise leisure time, making pleasures more efficient, as if they were little more than extensions of work.

Dara Birnbaum, Pop-Pop Video: Kojak/Wang, 1980. © Courtesy Dara Birnbaum and Eletrconic Arts Intermix (EAI), New York.

The most recent works in the exhibition are by Betty Danon: A Braque Piacerebbe il Computer?, How a Shade Had a Show and Rose Oser Eros (all 1991). As with our hypothetical engineer looking at the Ladik pieces, unless the viewer is given information beforehand, they might get the sense that technology hadn’t advanced much since Borchardt or Geiger made their pieces. If the viewer is not told the year in which Danon’s works were produced, it is unlikely they would associate these pieces with the launch of the world wide web or the releases of Word 2.0 and Windows Media Player (Microsoft), or Photoshop, QuickTime, and the PowerBook (Apple). This may, in fact, be an advantage for reflecting on our perceptual habits.

Rose Oser Eros, a rose, printed in black and white like a sketch found at the back of a high schooler’s exercise book, floats in a field of dots framed by the words “Rrose en prose”. Though this might seem like a nonsense mixture of French and English, as with how a minimal amount of computing knowledge shapes the viewer’s assumptions about other works, it is important to note that this refers to at least three things.

One is Marcel Duchamp’s gender-fluid alter ego Rrose Selavy, itself a pun on the phrase “C’est la vie”. Another is an extension of the wordplay in the title – in French oser means “to dare”, suggesting something about the risks involved in desiring just about anything at all (person, thing, or transhumanist melding of consciousness and hardware).

The third, meanwhile, is fully autoreferential: the writing we see isn’t prose but ornament, and thus the opposite of prose as traditionally defined (un-ornamented writing). After all, what we see here isn’t a rose, but a computer-generated image of a rose. If this seems obvious, it may only be because we so take image-making like this for granted that we can almost instinctively distinguish between a thing and an image. Even granting a certain amount of ambiguity, this distinction creates a contrast between the mechanical means by which this image of a rose was created and the romantic and erotic connotations that persist even though we know it is just an image. This, in turn, makes us think again about the nonsensical phrase (“rrose en prose”). If the viewer were to try to say these words aloud, they might stumble over their sibilance as the words detach from the broken stem of meaning.

The limited scope of Radical Software not only makes for a digestible exhibition but shows us just how much has changed in living memory. The computer is, like writing and the printing press, another extension of the human power of memory, enhancing its potential at the price of cutting us off from some kinds of interactions with other people. Radical Software not only reminds us of that but helps us to do the hard work of processing these upheavals which, like modernities of all kinds, come with a certain amount of unease, if not trauma.