David Kovats Gallery, Pop-Up Space, London

12 August – 19 September 2021

by JOE LLOYD

It is tempting when describing contemporary artists to reach towards precedents and influences. But I wonder how it feels for the artists so tagged. On the one hand, it offers a link to the past, a legitimising tie to established canons. On the other, it threatens to turn today’s practitioners into a footnote to what already exists, primarily worth contemplating as a tie to the past. Disciples of Dóra Maurer is a group exhibition whose featured artists have no such anxiety. All eight of them freely accept the impact Maurer (b1937, Budapest) has had on their practice.

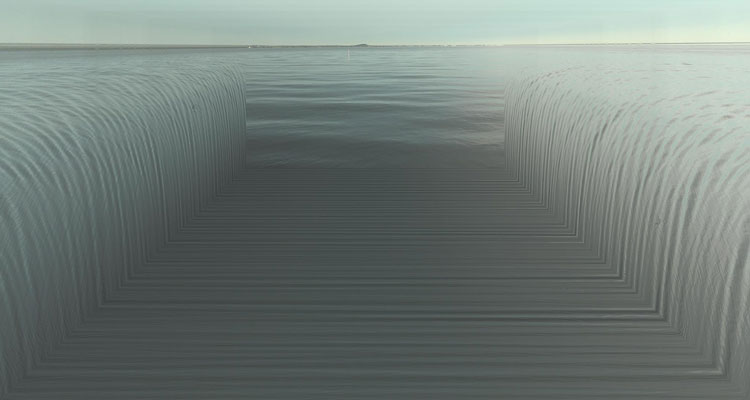

András Zalavári, Balaton IV, 2020. Photomontage, 69 x 120 cm. Photo courtesy of the Hungarian Cultural Centre, London.

London audiences will be familiar with Maurer from her recent retrospective at Tate Modern, which enlivened the museum for almost 18 months across 2019 and 2020, and from her concurrent exhibition at White Cube Bermondsey. But she has long been a significant figure in her native Hungary. According to Máté Vincze, director of the Hungarian Cultural Centre, she is Hungary’s “biggest contemporary artist”. Since the 1990s, she has also been a prolific teacher, teaching audiovisual practices at Budapest’s College of Applied Arts and painting at the Hungarian Academy of Fine Arts. She continues to supervise doctorates today, aged 84.

Mária Chilf, Mother-daughter, 2019. Stain, photocut on paper, 70 x 100 cm. Photo courtesy of the Hungarian Cultural Centre, London.

Disciples of Dora Maurer was privately exhibited at London’s Hungarian Embassy earlier this summer, before being publicly shown at David Kovats Gallery’s pop-up space on Shelton Street, Covent Garden. All the artists featured attended Maurer’s classes or had her as their doctoral supervisor. They span several generations, from Attila Csörgő (b1965) to András Zalavári (b1986). Some have especially close ties: Mária Chilf (b1966) worked as Maurer’s teaching assistant, while András Wolsky (b1969) has collaborated with Maurer as a part of her Open Structures Art Society, which organises exhibitions of geometric abstraction. All have immense respect for their master. “I can confidently say”, says Zoltán Szegedy-Maszák (b1969), “that I learned the most from Dóra Maurer about how to relate to art, the affirmation of life and joy, humanity – and when it comes to art, mischief against the canon.”

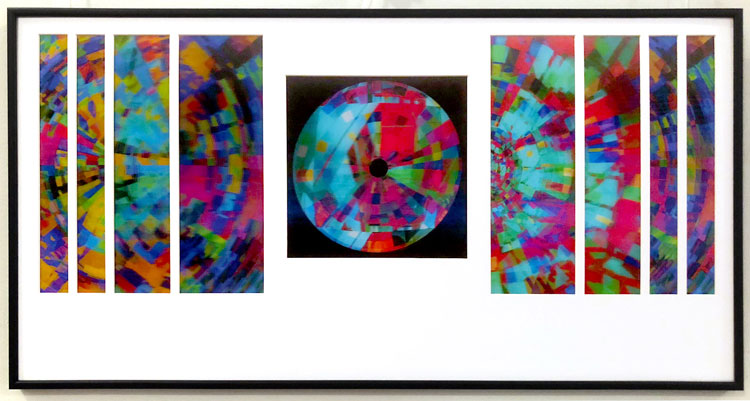

Zoltán Szegedy-Marsák, We Cannot See Clearly, 2018. Lenticular print, 40 x 78 cm. Photo courtesy of the Hungarian Cultural Centre, London.

In form and aesthetic, the eight artists are very different. In this, they might embody something of Maurer’s spirit. She is one of those postwar artists who seem to do everything. It can be difficult to pin down a signature Maurer. She was trained in graphic art and printmaking in the 50s and began her career working on paper. Though she has refuted a political reading of her practice, it was shaped by the cultural shift that came with the ill-fated Hungarian Revolution of 1956. By the 70s, she had added film, performance and photography to her repertoire, as well as developing a keen line in tricksy abstract painting. Since the 80s, she has focused on vibrantly coloured acrylic works, which seem to create three-dimensional space through interlocking forms and colours.

Attila Csörgö, Deviation 1 from the series Collisions and Deviations, 2018. Archival pigment print, 40 x 30 cm. Photo courtesy of the Hungarian Cultural Centre, London.

One through-line is a drive towards experimentation, making and breaking rules and systems. The journey is as important as the end product. Her approach was borne out in her teaching. Csörgő says of her audio-visual course: “She was more invested in the fruitful process of experimentation than the realisation of the project itself.” The same might be said of Csörgő’s work, which often replicates rudimentary scientific experiments. A pair of photographic prints here, Deviation 1 and 2 (both 2018), present inscrutable closeups of a large contraption, concealed in apparent darkness, leaving you to wonder at its potential purpose.

Barbara Nagy, Floating Shapes II, 2021. Painted, engraved word, 63 x 63 cm. Photo courtesy of the Hungarian Cultural Centre, London.

From a fleeting glance, Barbara Nagy’s (b1976) Floating Shapes II (2021) looks like a pitch-dark abstract painting, its sail-like shapes rendered in heavy impasto. But you would be wrong: it is a block of wood pared down in thick stripes. What looks like a building-up is a hollowing-out. Two works by Zalavári are even more cunning. Plane Tree Allée II (2019) shows an oddly dilated, pergola-like path through some greenery leading to a paradisal square of woodland, while Balaton IV (2020) shows the lake of that name – a place that looms large in the Hungarian imagination – parted like the Red Sea. Each turns nature into something glitchy and unreal. They were created by compressing video footage into a single image, compressing time and space: two of Maurer’s perennial concerns.

Márton Cserny, Series nr. 1, 2, 3, 2021. Stencil, canvas, 3 pieces each 40 x 40 cm. Photo courtesy of the Hungarian Cultural Centre, London.

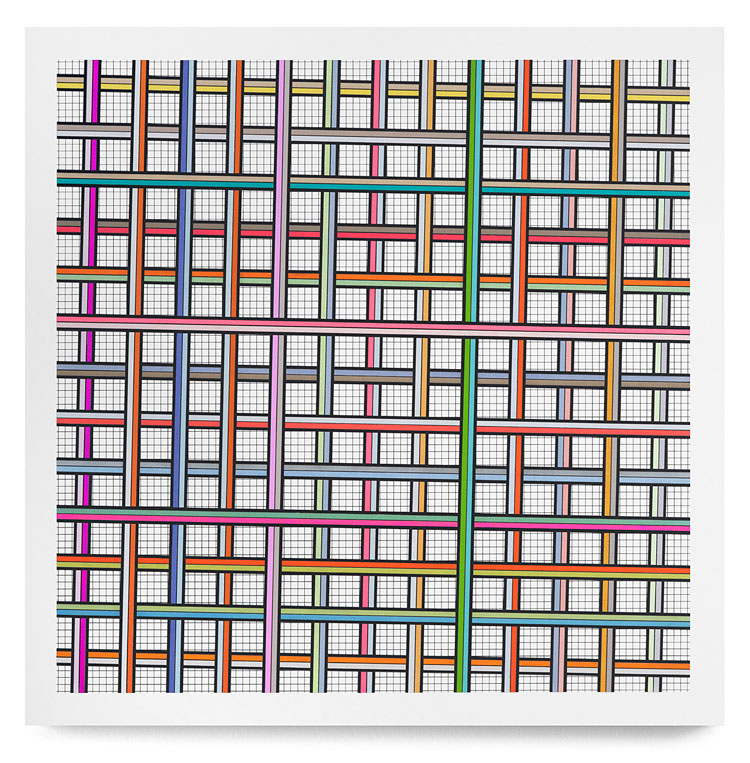

Unsurprisingly, there are also abstracts. Wolsky paints canvases of tessellating space, which he generates using a set of rules. Series nr 1, 2, 3 (2021) by Márton Cserny (b1970) twist a logic-defying form through several permutations. Szegedy-Maszák’s series We Cannot See Clearly (2018) uses lenticular lenses to create an almost hologram-like illusion of space, bursting in a panoply of colours. They remind me of the flecking hues that one sees when you close your eyes and look towards an artificial light source, bright and fleeting. But most eye-catching are a pair of oil, pencil and paint pieces by Tamás Jovánovics (b1974). These place a slightly askew grid of coloured stripes, like sticks of rock, over a pale, tighter graph paper-like grid. Although both grids are precisely measured, the diagonal colourations of the coloured ones and the seemingly irregular ways in which its bands intersect create a subtly mesmerising effect.

Tamás Jovánovics, Hybrid Hierarchy III, 2019. Oil-based colour pencil and acrylic paint on fibreboard, 102.5 x 102.5 cm. Photo courtesy of the Hungarian Cultural Centre, London.

Most of the artists featured in the exhibition echo Maurer’s mathematical streak and interest in process. The work of Chilf, which includes film and performance, connects to Maurer’s interest in human actions. She is represented here by two works on paper, both of which feature figures cut from photographs collaged on to ink-stand backgrounds. Faces aside, Chilf’s people are oddly disembodied, represented by the creases in their garments rather than the torso itself. Both scenes feature moments of joy – a mother posing with her daughter, a woman riding on a man’s shoulders. But there is something a little alarming about these grinning greyscale forms standing in ill-defined places, as if their smiles could give way at any moment. “My work”, Maurer told Studio International in 2016, “has been based on change, shifting, traces, temporality.” Chilf tackles these immaterial themes in a satisfyingly material way. Maurer can be proud of how broadly her lessons have been translated.

Abstract Erotic: Louise Bourgeois, Eva Hesse, Alice Adams

A groundbreaking New York show from 1966 is brought back to life with the work of three women whose ...

Jeremy Deller – interview: ‘I’m not looking for the next thing. I...

How did he go from asking a brass band to play acid house to filming former miners re-enacting a sem...

Encounters: Giacometti x Huma Bhabha

The first of three exhibitions to position historic sculptures by Alberto Giacometti with new works ...

The Parisian scenes that Edward Burra is known for are joyful and sardonic, but his work depicting t...

The 36th Ljubljana Biennale of Graphic Arts: The Oracle

Surprising, thrilling, enchanting – under the artistic direction of Chus Martínez, the works in t...

It’s Terrible the Things I Have to Do to Be Me: On Femininity and Fame ...

In a series of essays about pairs of famous women, the cultural critic Philippa Snow explores the co...

Paul Thek: Seized by Joy. Paintings 1965-1988

A rare London show of elusive queer pioneer Paul Thek captures a quieter side of his unpredictable p...

This elegantly composed exhibition celebrates 25 years’ of awards to female artists by Anonymous W...

The first of its kind, this vast show is a stunning tour of the realism movement of the 1920s and 30...

Maggi Hambling: ‘The sea is sort of inside me now … [and] it’s as if...

Maggi Hambling’s new and highly personal installation, Time, in memory of her longtime partner, To...

Caspar Heinemann takes us on a deep, dark emotional dive with his nihilistic installation that refer...

Complex, multilayered paintings and sculptures reek of the dark histories of slavery and colonialism...

Shown in the context of the historic paintings of Dulwich Picture Gallery, Rachel Jones’s new pain...

William Mackrell – interview: ‘I have an interest in dissecting the my...

William Mackrell's work has included lighting 1,000 candles and getting two horses to pull a car. No...

Marina Tabassum – interview: ‘Architecture is my life and my lifestyle...

The award-winning Bangladeshi architect behind this year’s Serpentine Pavilion on why she has shun...

A cabinet of curiosities – inside the new V&A East Storehouse

Diller Scofidio + Renfro has turned the 2012 Olympics broadcasting centre into a sparkling repositor...

Plásmata 3: We’ve met before, haven’t we?

This nocturnal exhibition organised by the Onassis Foundation’s cultural platform transforms a pub...

Ruth Asawa: Retrospective / Wayne Thiebaud: Art Comes from Art / Walt Disn...

Three well-attended museum exhibitions in San Francisco flag a subtle shift from the current drumbea...

This dazzling exhibition on the centenary of John Singer Sargent’s death celebrates his versatile ...

Through film, sound and dance, Emma Critchley’s continuing investigative project takes audiences o...

Rijksakademie Open Studios: Nora Aurrekoetxea, AYO and Eniwaye Oluwaseyi

At the Rijksakademie’s annual Open Studios event during Amsterdam Art Week, we spoke to three arti...

AYO – interview: Rijksakademie Open Studios

AYO reflects on her upbringing and ancestry in Uganda from her current position as a resident of the...

Eniwaye Oluwaseyi – interview: Rijksakademie Open Studios

Eniwaye Oluwaseyi paints figures, including himself, friends and members of his family, within compo...

Nora Aurrekoetxea – interview: Rijksakademie Open Studios

Nora Aurrekoetxea focuses on her home in Amsterdam, disorienting domestic architecture to ask us to ...

Kiki Smith – interview: ‘Artists are always trying to reveal themselve...

Known for her tapestries, body parts and folkloric motifs, Kiki Smith talks about meaning, process, ...

Frank Auerbach, Britain’s greatest postwar painter, has a belated German homecoming, which capture...

How Painting Happens (and why it matters) – book review

Martin Gayford’s engrossing book is a goldmine of quotes, anecdotes and insights, from why Van Gog...

Jonathan Baldock – interview: ‘Weird is a word that’s often used to...

As a Noah’s ark of his non-binary stuffed toys goes on show at Jupiter Artland, Jonathan Baldock t...

Helen Chadwick: Life Pleasures

Helen Chadwick’s unwillingness to accept any binary division of the world allowed her to radically...

Catharsis: A Grief Drawn Out – book review

To what extent can the visual language of grief be translated? Janet McKenzie looks back over 20 yea...