Hollis Taggart, New York

29 April – 31 May 2021

by ELIZABETH BUHE

The story of Michael West’s fate risks becoming synecdochical for the work itself, so astonishing is it that a first-rate abstract expressionist could remain virtually unknown, despite the revisionist efforts that have accelerated over the past two decades. A onetime student of Hans Hofmann at the Arts Students League of New York and partner of Arshile Gorky in the 1930s, West (1908-91) painted bold abstract canvases with confident strokes that instantly confirm her kinship with practitioners of abstraction in New York from the 1940s onward. But unlike the list of usual male suspects, such as Franz Kline or Jackson Pollock, West died in obscurity, impoverished, on the Upper West Side in 1991; unlike her peers, Lee Krasner, Elaine de Kooning or Helen Frankenthaler, West was not allied to a critically lauded male artist, though she did rebuff several proposals from Gorky.

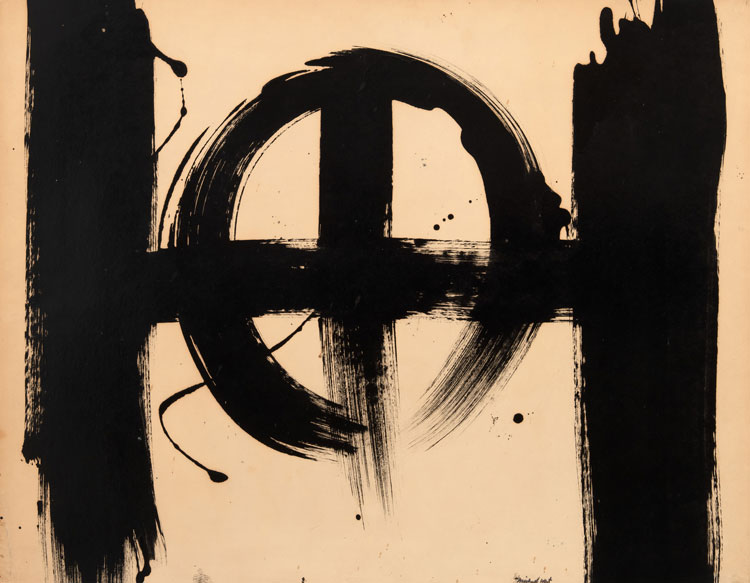

Michael West, Speed, 1970. Enamel on Oak Tag mounted on canvas, 22 x 28 in (55.9 x 71.1 cm). Image courtesy of Hollis Taggart Gallery.

Steely individualism, then, was a gender-contingent virtue, as West, who changed her name from Corinne to Michael in 1941, knew. In 1996, the Pollock-Krasner House and Study Center mounted a West retrospective, and her name punctuates a few recent catalogues, including Joan Marter’s Women of Abstract Expressionism organised for the Denver Art Museum in 2016. Until Hollis Taggart’s survey in 2019, the work was inaccessible in any depth. This is entirely circumstantial in light of the debilitating sexism we now know female painters of West’s generation endured, particularly so given the masculinist posturing of her chosen cohort. We owe the paintings’ current availability in large part to the photographer and collector Stuart Friedman, who owned West’s work, purchased the contents of her apartment at a municipal sale following her death, and subsequently sold the archive and paintings to Taggart.

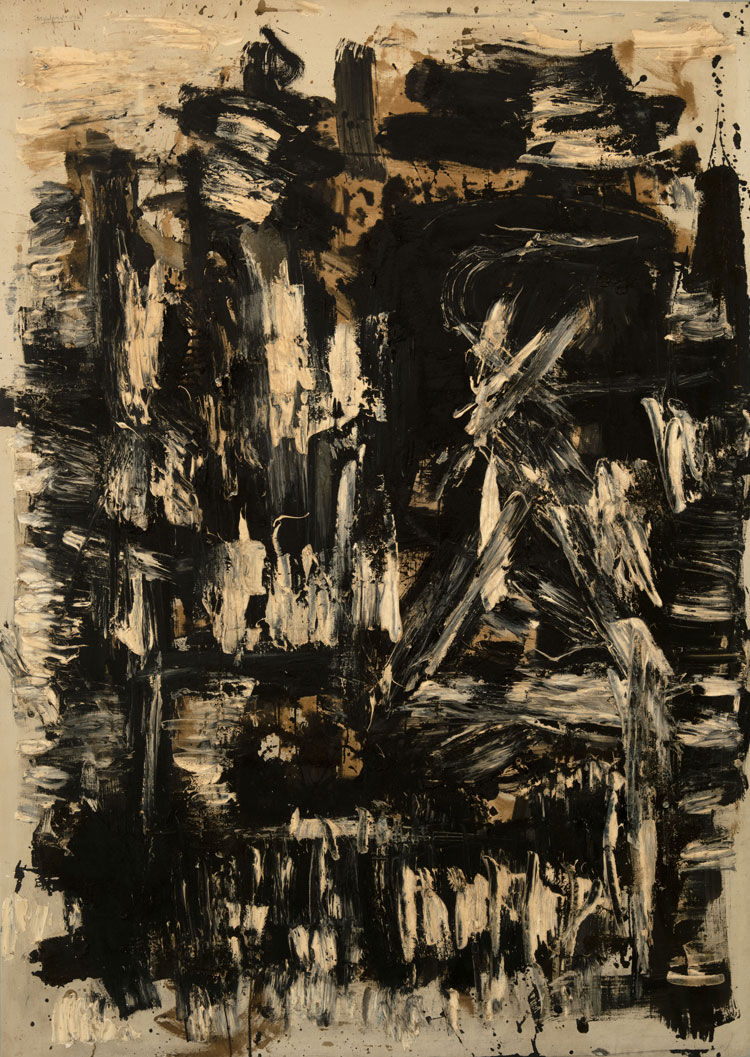

Michael West, White Writing, 1966. Oil on canvas, 59 5/8 x 47 1/2 in (151.4 x 120.7 cm). Image courtesy of Hollis Taggart Gallery.

Epilogue examines West’s primarily monochrome work in black, white, grey and caramel tones in which oil is applied thickly with brushes of varying widths, a palette knife, and perhaps even straight from the tube, as in White Writing (1966), where peaked deposits suggest the tube was held momentarily at the end of several downward strokes. Most works date from 1964 to the mid-70s, with two outliers (both Untitled) from 1947 and 1948, years that saw the inauguration of Pollock’s drip technique, Mark Rothko’s multiforms and Barnett Newman’s zips, as well as the suicide of Gorky. Thus the inclusion of these earlier works, from the moment when abstract expressionism coalesced as a movement, solidify West’s participation right from the start. The swirling cacophony of Untitled’s (1948) triangles and circles in blue, white and black share a jigsaw-puzzle-like interlocking of forms that recalls Krasner’s contemporaneous Little Image paintings and evidences West working through the mythic symbols and scumbled surface texture of Richard Pousette-Dart, a friend.

Michael West, Untitled, 1948. Oil and sand on canvas, 31 x 21 in (78.7 x 53.3 cm). Collection of the Wen Long Cultural Foundation, Taiwan. Image courtesy of Hollis Taggart Gallery.

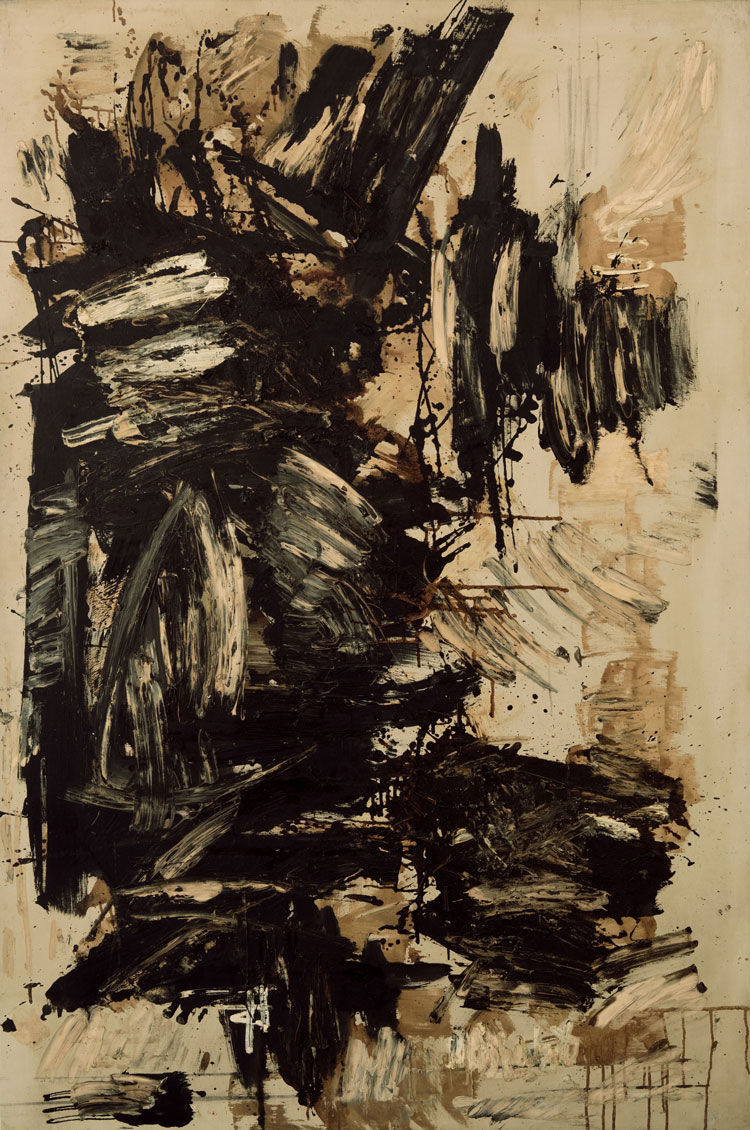

The 60s and 70s paintings that are the focus of this show fall into at least two bodies of work. The canvases from 1964 to 1969 show West pushing dense expanses of black paint across the canvas, out toward its edges, often as a ground for marks in contrasting hues. Sometimes, these marks form blocky patches resulting from the repetition of a scratch-like staccato gesture, as in The Eclipse (Eclipse in Reverse) (1964-67).

Michael West, The Eclipse (Eclipse in Reverse), 1964–7. Oil on canvas, 69 3/4 x 49 1/2 in (177.2 x 125.7 cm). Image courtesy of Hollis Taggart Gallery.

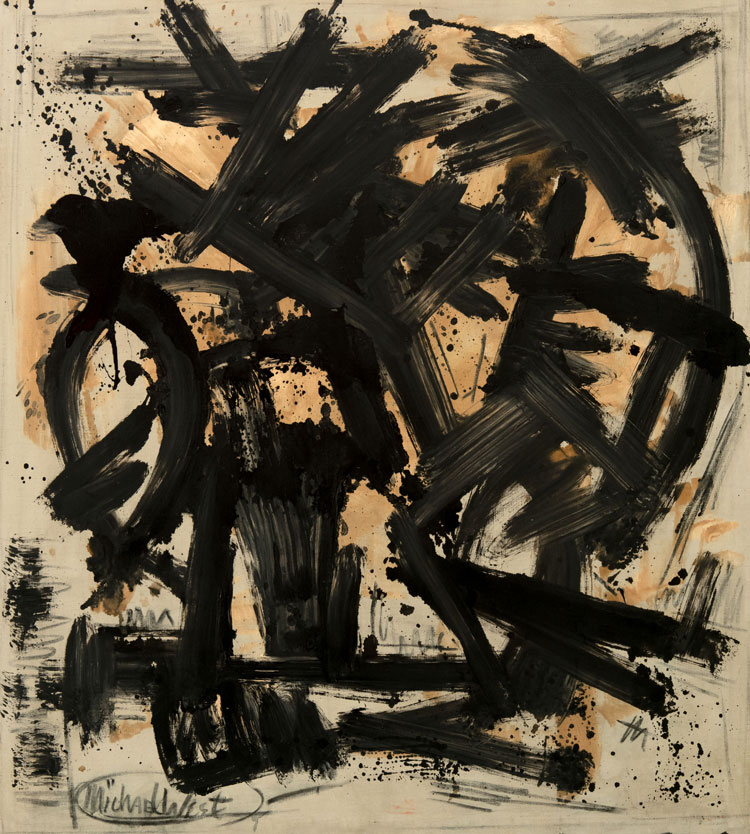

Michael West, Beginnings, 1968. Oil and charcoal on canvas, 51 1/8 x 46 in (129.9 x 116.8 cm). Collection of the Wen Long Cultural Foundation, Taiwan. Image courtesy of Hollis Taggart Gallery.

Elsewhere an armature of intersecting black lines structures the composition like the branches of a tree, as in Beginnings (1968). Often, West appears to have worked wet into wet, her loaded brush picking up the black underneath. She achieved compositional unity by consistently echoing the orientation of her marks within a given painting. The white strokes that lilt upward from left to right in the upper third of Epigraph (1966), for instance, resonate with those floating against a primed ground in the canvas’s lower right corner.

Michael West, Epigraph, 1966. Oil on canvas, 74 5/8 x 49 1/2 in (189.5 x 125.7 cm). Collection of the Wen Long Cultural Foundation, Taiwan. Image courtesy of Hollis Taggart Gallery.

The work changed in about 1970, when West’s structure bent towards horizontals and verticals, her brush strokes tightened up to become almost calligraphic, she decreased the density of her paint, and she reduced her palette, though not exclusively, to black and white. Of this later period, Study (1970) is an exemplary minimalist canvas featuring a sole black band intersected by a narrower strip at a right angle, like a tipped-over T. Atop an uneven washy white ground, its simplicity is offset by a restrained yet assured spattering of black paint. Several canvases feature a circle containing a cross, an intriguing symbol that must have held special import for the artist.

Michael West, Study, 1965. Oil on canvas, 50 x 30 inches (127 x 76.2 cm). Image courtesy of Hollis Taggart Gallery.

West’s grisaille palette, planes of brushstrokes fractured across the surface, all-over composition, and linear rather than gestural or biomorphic structure suggest her debt to cubism rather than surrealism, which motivated so much abstract expressionist painting. For Pollock and Gorky, surrealism was a means of subverting the strictures of conscious thought and the limitations of tradition. But West’s path to abstraction demonstrates instead a sustained interest in selectively appropriating from the culture around her, as did Betty Parsons, rather than isolating and exploring a single influence or technique with such focus that it would become her signature, as did Rothko and Pollock.

Michael West, Nyo Ze Tai, 1975. Oil on canvas, 52 x 18 in (132.1 x 45.7 cm). Image courtesy of Hollis Taggart Gallery.

West’s titles, especially, point to an awareness of abstract painting as part and parcel of a new and ever-changing global (rather than American) order; Dagger of Light (1951) and Nihilism (1949) (neither of which are in this show) gesture towards nuclear holocaust, whereas White Writing (1966) acknowledges Mark Tobey and Nyo Ze Tai (1975) records mid-century abstraction’s desire to circumvent European precedent by routing itself through Asian art instead. The nails embedded in Invisible Numbers (1969), one of the strongest paintings in the show, respond to Pollock, while the same work’s scabs of paint evidence West’s interest in the materiality of European painters such as Jean Fautrier or Jean Dubuffet. With this receptivity comes a willingness to take risks and to stand against the stable identity associated with stylistic uniformity.

Michael West, Invisible Numbers, 1969. Oil and nails on canvas, 66 1/2 x 44 in (168.9 x 111.8 cm). Image courtesy of Hollis Taggart Gallery.

In photographs printed in the catalogue, West appears pensive, a self-fashioning apropos of a writer, painter and poet. This paper archive awaits full treatment (a catalogue raisonné is underway), but several documents reproduced in the 2019 catalogue affirm their richness. “To paint the dream world is only a part,” West wrote, “[it] is to miss the whole world which to me is more exciting – since it includes everything and thus gives opportunity for greater and more minute analysis of feeling.” The sense of empathy these words impart – in addition to the paintings – are a welcome corrective to art history as we know it.

Slavs and Tatars: The Contest of the Fruits

Rapping fruit, legendary birds and nail art feature in the UK debut of the Berlin-based collective S...

Liverpool Biennial 2025: Bedrock

From Sheila Hicks’s gemstone-like sculptures to Elizabeth Price’s video essay on modernist Catho...

Mikhail Karikis – interview: ‘What is the soundscape of the forthcomin...

Mikhail Karikis explains the ideas behind his new sound and video installation calling for action ag...

Art & the Book* and Spineless Wonders: The Power of Print Unbound**

Two concurrent exhibitions bring special collections into broader spaces of circulation, highlightin...

Focusing on the skills of wallpaper design and embroidery, this exhibition tells the story of the ...

Daphne Wright: Deep-Rooted Things

This show is a celebration of the domestic, and the poignant sculpture of Wright’s two sons, now o...

Anna Boghiguian: The Sunken Boat: A Glimpse into Past Histories

The venerable Egyptian Canadian installation artist Anna Boghiguian brings shipwrecks, shells and th...

Abstract Erotic: Louise Bourgeois, Eva Hesse, Alice Adams

A groundbreaking New York show from 1966 is brought back to life with the work of three women whose ...

Jeremy Deller – interview: ‘I’m not looking for the next thing. I...

How did he go from asking a brass band to play acid house to filming former miners re-enacting a sem...

Encounters: Giacometti x Huma Bhabha

The first of three exhibitions to position historic sculptures by Alberto Giacometti with new works ...

The Parisian scenes that Edward Burra is known for are joyful and sardonic, but his work depicting t...

The 36th Ljubljana Biennale of Graphic Arts: The Oracle

Surprising, thrilling, enchanting – under the artistic direction of Chus Martínez, the works in t...

It’s Terrible the Things I Have to Do to Be Me: On Femininity and Fame ...

In a series of essays about pairs of famous women, the cultural critic Philippa Snow explores the co...

Paul Thek: Seized by Joy. Paintings 1965-1988

A rare London show of elusive queer pioneer Paul Thek captures a quieter side of his unpredictable p...

This elegantly composed exhibition celebrates 25 years’ of awards to female artists by Anonymous W...

The first of its kind, this vast show is a stunning tour of the realism movement of the 1920s and 30...

Maggi Hambling: ‘The sea is sort of inside me now … [and] it’s as if...

Maggi Hambling’s new and highly personal installation, Time, in memory of her longtime partner, To...

Caspar Heinemann takes us on a deep, dark emotional dive with his nihilistic installation that refer...

Complex, multilayered paintings and sculptures reek of the dark histories of slavery and colonialism...

Shown in the context of the historic paintings of Dulwich Picture Gallery, Rachel Jones’s new pain...

William Mackrell – interview: ‘I have an interest in dissecting the my...

William Mackrell's work has included lighting 1,000 candles and getting two horses to pull a car. No...

Marina Tabassum – interview: ‘Architecture is my life and my lifestyle...

The award-winning Bangladeshi architect behind this year’s Serpentine Pavilion on why she has shun...

A cabinet of curiosities – inside the new V&A East Storehouse

Diller Scofidio + Renfro has turned the 2012 Olympics broadcasting centre into a sparkling repositor...

Plásmata 3: We’ve met before, haven’t we?

This nocturnal exhibition organised by the Onassis Foundation’s cultural platform transforms a pub...

Ruth Asawa: Retrospective / Wayne Thiebaud: Art Comes from Art / Walt Disn...

Three well-attended museum exhibitions in San Francisco flag a subtle shift from the current drumbea...

This dazzling exhibition on the centenary of John Singer Sargent’s death celebrates his versatile ...

Through film, sound and dance, Emma Critchley’s continuing investigative project takes audiences o...

Rijksakademie Open Studios: Nora Aurrekoetxea, AYO and Eniwaye Oluwaseyi

At the Rijksakademie’s annual Open Studios event during Amsterdam Art Week, we spoke to three arti...

AYO – interview: Rijksakademie Open Studios

AYO reflects on her upbringing and ancestry in Uganda from her current position as a resident of the...

Eniwaye Oluwaseyi – interview: Rijksakademie Open Studios

Eniwaye Oluwaseyi paints figures, including himself, friends and members of his family, within compo...