The Ben Uri Gallery, London

16 June – 17 September 2021

by BRONAĊ FERRAN

Becoming Gustav Metzger: Uncovering the Early Years, 1945-1959, co-curated by Nicola Baird and Leanne Dmyterko, will appeal to anyone interested in the pre-history of Metzger as an artist, before the launch of his first “auto-destructive art” manifesto in 1959. What becomes strongly evident to the visitor to this exhibition is that the early Metzger was intensively trying out various styles, approaches and techniques, in an active search for his own métier. Organised by the Ben Uri Research Unit and the Gustav Metzger Foundation, with an accompanying publication and discussion series, it draws new attention in particular to Metzger’s relation to David Bomberg, a renowned artist as well as Metzger’s art teacher and confidante from 1945-46 and again from 1949-1953, at the Borough Polytechnic, now South Bank University in London.

Gustav Metzger, Table, 1956. Oil on canvas. Courtesy of The Gustav Metzger Foundation.

From the useful interpretative commentary on the walls of the gallery, one might conclude that Metzger’s participation in classes in life drawing with the “later” Bomberg – classes also attended by fellow Jewish-born artists Frank Auerbach and Leon Kossoff – provided a crucial whetstone for Metzger in terms of clarifying his own direction. Among items shown within the vitrines in the exhibition is a letter from Bomberg to Metzger, effectively closing down their relationship in late 1953, a scenario that Baird analyses more closely in her illuminating essay in the catalogue.

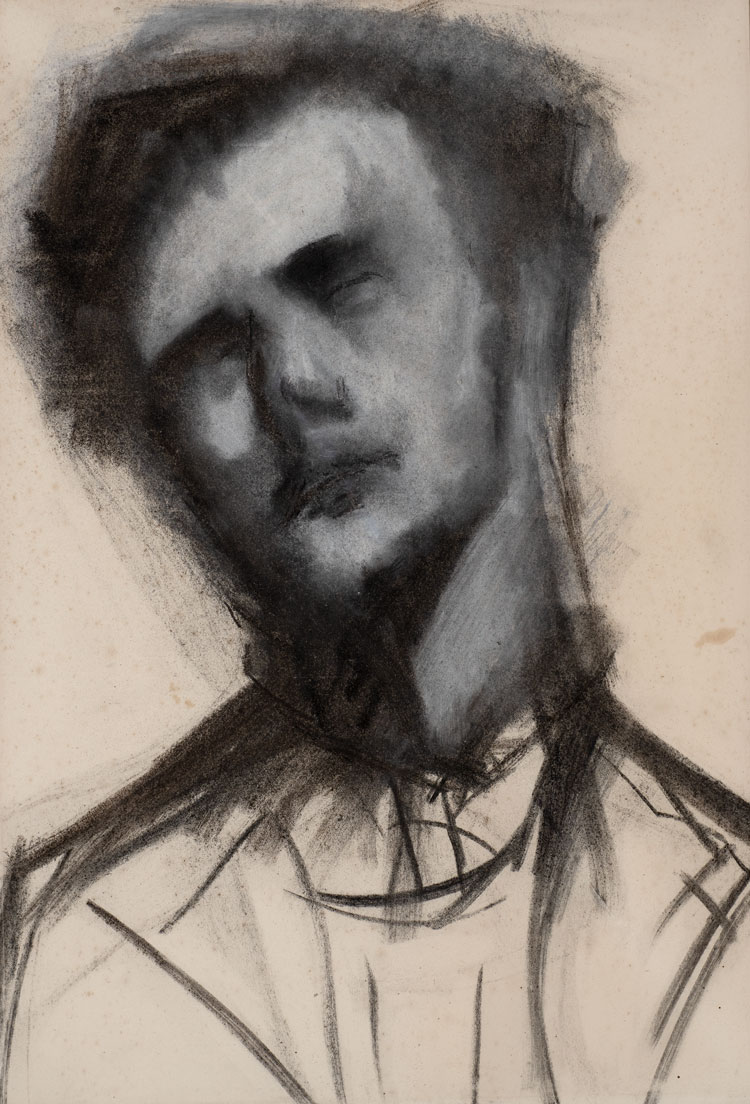

Gustav Metzger, Head of a Man, 1952. Chalk on paper. Courtesy of The Gustav Metzger Foundation.

The co-curators have used the narrow gap between left and right-hand walls in the gallery to establish a counterpointing dialogue between figuration and its opposite, the interplay of which I also view as formative in the shaping of Metzger’s practice. Indeed, Henry Moore’s response to Metzger’s offer to become his assistant in 1945, advising Metzger to initially gain skills in life-drawing, was probably a factor prompting Metzger’s pursuit of related skills over the following seven years. Of the 24 works on physical display in this exhibition, 13 are figuratively related. However, what becomes vividly apparent on viewing the array of portraits shown on the left-hand wall of the gallery is that Metzger was never an effective portraitist in a straightforward sense, perhaps again hinting at the destruction of self that the term “auto-destruction” later indicated.

Gustav Metzger, Head of E. Royalton-Kisch, 1950. Oil on canvas. Courtesy of The Gustav Metzger Foundation.

A portrait of Ernest Royalton-Kisch, dated 1950, has been used as the lead visual image for the Ben Uri exhibition. A former military captain and then solicitor, Royalton-Kisch was significantly helpful to Metzger in terms of his professional development, although, apparently, he refused to accept the portrait when it was offered to him by Metzger. Importantly, perhaps, in an interview in 2012, Metzger told me of a personal struggle he felt during the 50s when “circling Judaism with respect to its prohibition on making images of the human figure” and questioning “how might a Jewish person make art”. So, too, a work entitled Antwerp Model, dated 1949, on display in this exhibition, appears to be leaning towards a primitivism that belies the task of facial representation.

Gustav Metzger, Self Portrait, An Undefiled, 1946. Oil on canvas. Courtesy of The Gustav Metzger Foundation.

Among paintings recovered when a seemingly lost collection of Metzger’s early material was found in a relative’s attic in north London in 2014, is a work entitled in the original German, Selbst Bildnis Eines Unbeflecken AD 1946. This is translated by the curators as Self-Portrait: An Undefiled, although the term “unsullied” may perhaps be more apposite. I read this work as “Gustav in embryo”: as if depicting the inner chimera of a numinous self, recognisably that of a youthful Metzger, en-wombed in a fluidity of elements, with genitals on show, yet with an overall atmosphere of vagueness. In her essay, Baird tells us that Metzger became preoccupied in the second half of the 40s with areas of embryology, in parallel to taking classes with Bomberg, thus progressing what Metzger subsequently described as “a surrealistic phase” in his practice.

Gustav Metzger, Dissolution of the City, 1946. Oil on canvas. Courtesy of The Gustav Metzger Foundation.

Hanging on the opposite wall are two other early works, entitled Dissolution of the City and Eroica, Funeral March, both also dated 1946. These reveal Metzger’s relatively assured way, at the age of 20, with depersonalised dimensions, with a series of intersecting lines and colours, that combine and flow together as if in musical sequence. In both instances, we sense that Metzger is engaging psychologically with the displacements of the war and its related tragic consequences for many, including his parents and his elder brother who were murdered by the National Socialists. A related political consciousness duly becomes a more dominant topic within Metzger’s works from the mid-50s onwards; we see this initially diffusing his art practice in a series of interpretations of a table, where he incrementally breaks up the held object into dismantled and disintegrating sequences, responding, as he has also referred in personal interview, to images of the Bikini Atoll nuclear tests in early 1954.

Gustav Metzger, Eroica, Funeral March, 1946. Oil on canvas. Courtesy of The Gustav Metzger Foundation.

As a result of this exhibition, Metzger has been added to the growing database developed by the Ben Uri Research Unit of Jewish artists, as well as a wider immigrant community of artists who have adopted Britain as their home. Materials on show have been borrowed from the Gustav Metzger Foundation’s collection, much of which is still in the process of being catalogued, with hundreds of drawings and other items awaiting thorough analysis and, indeed, conservation. Despite being notorious before his death in March 2017 for his anti-capitalist stance, aspects of this posthumous work are now being supported by the leading global cultural powerhouse Hauser & Wirth, which is currently presenting works by Metzger, including an installation of his “auto-creative” liquid crystal light-based practices, at its space in Somerset. Hauser & Wirth has announced the Metzger exhibition as “the first of the gallery’s global projects to implement a new carbon budget”, informed by Metzger’s strong urging in the last decade of his life in particular to “remember nature” as a counteraction to species extinction by destructive human forces.

Gustav Metzger, at Hauser & Wirth, Somerset, runs until 12 September 2021.

Shown in the context of the historic paintings of Dulwich Picture Gallery, Rachel Jones’s new pain...

William Mackrell – interview: ‘I have an interest in dissecting the my...

William Mackrell's work has included lighting 1,000 candles and getting two horses to pull a car. No...

Marina Tabassum – interview: ‘Architecture is my life and my lifestyle...

The award-winning Bangladeshi architect behind this year’s Serpentine Pavilion on why she has shun...

A cabinet of curiosities – inside the new V&A East Storehouse

Diller Scofidio + Renfro has turned the 2012 Olympics broadcasting centre into a sparkling repositor...

Plásmata 3: We’ve met before, haven’t we?

This nocturnal exhibition organised by the Onassis Foundation’s cultural platform transforms a pub...

Ruth Asawa: Retrospective / Wayne Thiebaud: Art Comes from Art / Walt Disn...

Three well-attended museum exhibitions in San Francisco flag a subtle shift from the current drumbea...

This dazzling exhibition on the centenary of John Singer Sargent’s death celebrates his versatile ...

Through film, sound and dance, Emma Critchley’s continuing investigative project takes audiences o...

Rijksakademie Open Studios: Nora Aurrekoetxea, AYO and Eniwaye Oluwaseyi

At the Rijksakademie’s annual Open Studios event during Amsterdam Art Week, we spoke to three arti...

AYO – interview: Rijksakademie Open Studios

AYO reflects on her upbringing and ancestry in Uganda from her current position as a resident of the...

Eniwaye Oluwaseyi – interview: Rijksakademie Open Studios

Eniwaye Oluwaseyi paints figures, including himself, friends and members of his family, within compo...

Nora Aurrekoetxea – interview: Rijksakademie Open Studios

Nora Aurrekoetxea focuses on her home in Amsterdam, disorienting domestic architecture to ask us to ...

Kiki Smith – interview: ‘Artists are always trying to reveal themselve...

Known for her tapestries, body parts and folkloric motifs, Kiki Smith talks about meaning, process, ...

Frank Auerbach, Britain’s greatest postwar painter, has a belated German homecoming, which capture...

How Painting Happens (and why it matters) – book review

Martin Gayford’s engrossing book is a goldmine of quotes, anecdotes and insights, from why Van Gog...

Jonathan Baldock – interview: ‘Weird is a word that’s often used to...

As a Noah’s ark of his non-binary stuffed toys goes on show at Jupiter Artland, Jonathan Baldock t...

Helen Chadwick: Life Pleasures

Helen Chadwick’s unwillingness to accept any binary division of the world allowed her to radically...

Catharsis: A Grief Drawn Out – book review

To what extent can the visual language of grief be translated? Janet McKenzie looks back over 20 yea...

Radical Software: Women, Art & Computing 1960-1991

With more than 100 works by 50 artists, this show examines the pioneering role of women in computer ...

Dame Jillian Sackler, the art lover and philanthropist, has died aged 84...

Giuseppe Penone: Thoughts in the Roots

With numerous works created with the twigs, leaves, roots, branches and majestic forms of trees, thi...

Solange Pessoa: Pilgrim Fields

An olfactory orgy of marigolds, chamomile, grasses, sheepskins and kelp is arranged into a surreal l...

Christian Krohg: The People of the North

A key figure in Norwegian art, naturalist painter Christian Krohg wanted his art to bring social cha...

This comprehensive show charts the groundbreaking rise of the illustrated poster in 19th-century Fra...

Caspar David Friedrich: The Soul of Nature

This comprehensive show celebrating last year’s 250th anniversary of the Romantic painter’s birt...

A humongous survey of contemporary painting in Belgium shows a medium embracing the burden of its hi...

A retrospective of the first 20 years of the Max Mara Art Prize for Women finds an inexhaustible wel...

This new work is very much about indeterminate selfhood as Nora Turato immerses the visitor in a swi...

Burmese artist Htein Lin has been jailed many times and this show includes some of the remarkable pa...

This retrospective brings the acclaimed and trailblazing, but nearly forgotten French modernist arti...