Htein Lin. The Fly (2005), video, colour, sound, 7:39 minutes. Installation view, Htein Lin, Escape, Ikon Gallery, 2025. Image courtesy Ikon. Photo: David Rowan.

Ikon Gallery, Birmingham

20 March – 1 June 2025

by DAVID TRIGG

The line between tragedy and comedy wears thin in Htein Lin’s The Fly (2005), which sees the Burmese artist confined to a chair as he struggles against an invisible fly buzzing around his head. The agitated performance, a recording of which is on show at Birmingham’s Ikon Gallery as part of Lin’s major solo exhibition Escape, was conceived while he was imprisoned in a Myanmar jail and takes inspiration from George Langelaan’s 1957 short story of the same name, in which a stray insect causes a scientific experiment to go horribly wrong. The narrative reminded Lin of the flies he encountered while being interrogated, a painful time referenced by the performance, which is both humorous and unsettling. Part way through, Lin ostensibly becomes the insect, briefly finding liberation before retiring to his seat – an allusion to the cycles of detention and freedom that have shaped his life and work.

Born in 1966 in the tiny village of Mezaligon, in the Ayeyarwady region of Burma (renamed Myanmar in 1989), Lin was raised in a climate of political upheaval. As a law student in Yangon, he became involved in the 1988 pro-democracy uprising, which saw large-scale demonstrations against the totalitarian Burma Socialist Programme Party. Following a violent military coup, he spent two years in a refugee camp on the Indian border, where he developed his visual art skills under the tutelage of the Mandalay artist and political activist Sitt Nyein Aye.

After joining the All Burma Students’ Democratic Front (ABSDF), a resistance movement that fought for democracy and human rights, Lin was accused of plotting opposition protests against the country’s military regime and he was subsequently jailed from 1998 to 2004. After several years of freedom, he was returned to prison in 2022 on spurious charges (along with his wife, the former British ambassador to Myanmar, Vicky Bowman), and though he was released three months later, he is not allowed a passport and remains in Myanmar, separated from his UK-based family.

Htein Lin. 000235 (1998-2004). Installation view, Htein Lin, Escape, Ikon Gallery, 2025. Image courtesy Ikon. Photo: David Rowan.

This exhibition, Lin’s first full retrospective in the UK, spans 30 years of work, including a significant selection from the remarkable body of paintings and drawings he created while held as a political prisoner. Titled 000235 (1998-2004), the series is named for the prisoner number assigned to him by the International Committee of the Red Cross. It is a wonder that Lin was able to make art at all in the strict Myanmar prison system, but he managed to produce about 1,000 paintings and drawings, several hundred of which were smuggled out of his cell. Prison uniforms, pillowcases and bed linen became his canvases, while blocks of soap, the tops of toothpaste tubes, rollers from cigarette lighters and the artist’s fingers were variously employed as improvised brushes. Painting was officially forbidden in prison so every mark he made represented a risk.

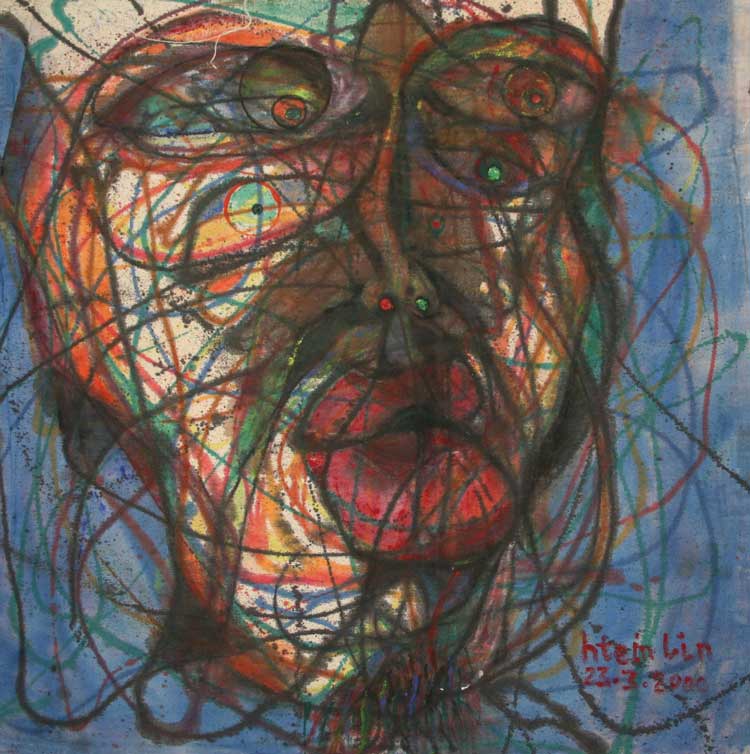

Htein Lin, Self-portrait, 2000. Oil paint on textile. © Courtesy the artist.

Working in a flat and at times almost childlike style, Lin’s figurative and non-representational paintings span a range of subjects, their often exuberant and unrestrained appearance belying the harsh conditions of their making. Some are sombre self-portraits, while others denote significant occasions, such as Happy New Year (2000), a riot of colourful marks that evoke exploding fireworks and perhaps a sense of optimism for the future. Others, including Waiting for Father (2000), which depicts a mother and a young child, reflect Lin’s longing for his family.

Htein Lin, Sitting at Iron Gate, 2002, from the series 000235 (1998-2004). Acrylic and vinyl paint on textile. © Courtesy the artist.

Sitting at the Gate of Prison (2000) reflects the conditions at Mandalay prison, where new prisoners were made to sit at the gates, hunched over while waiting to be processed. Here, the prisoners appear emaciated and full of despair. In Sitting at Iron Gate (2002) four figures sit with interlocking limbs, their heads reduced to large, single eyes, their innards illuminated by light bulbs in a reference to the inner light of Buddhist belief. Lin’s Buddhism, and specifically his daily Vipassana meditation, which is evoked by works such as Parinirvana (2000), provided him with much strength while in solitary confinement.

.jpg)

Htein Lin, When I was a Lousy Millionaire, 2022. Video, colour, sound, 24:56 minutes. © Courtesy the artist.

Flies are not the only pest to have plagued Lin while he was detained. The video When I was a Lousy Millionaire (2022) recounts the trauma of becoming infested with body lice, just one of the many torturous experiences he endured while chained up in a freezing mountain cell near the Chinese border in the early 90s. The work is based on a chapter of his 2014 memoir, Ma-Pa – the ABSDF Northern Branch Affair, which recounts the nine months he spent imprisoned at the hands of a rival student group. It is a harrowing watch as Lin narrates his chilling story while drawing simple yet disturbingly graphic illustrations of the barbaric treatment that he and his fellow prisoners endured.

.jpg)

Htein Lin, A Show of Hands, 2013-ongoing. Plaster sculpture. Installation view, Htein Lin, Escape, Ikon Gallery, 2025. Image courtesy Ikon. Photo: David Rowan.

Since he was released from prison in 2004, Lin has been a prominent voice in the call for freedom of speech and human rights in Myanmar. His ongoing sculptural project A Show of Hands (2013-) comprises hundreds of plaster sculptures taken from the hands of former political prisoners, each one representing an individual sacrifice of freedom. The hands are accompanied by a card detailing the circumstances surrounding the individual’s arrest and imprisonment; one woman, Moe Kalyar Oo, spent more than six years in jail for singing revolutionary student songs at the funeral ceremony of former Prime Minister U Nu. Nearly 500 hands have been cast to date (just 12 are on display at Ikon), and Lin plans to continue the project as detentions persist. Indeed, since the 2021 coup, in which the military seized power from Aung San Suu Kyi’s democratically elected government, thousands have been imprisoned in Myanmar, including Suu Kyi herself.

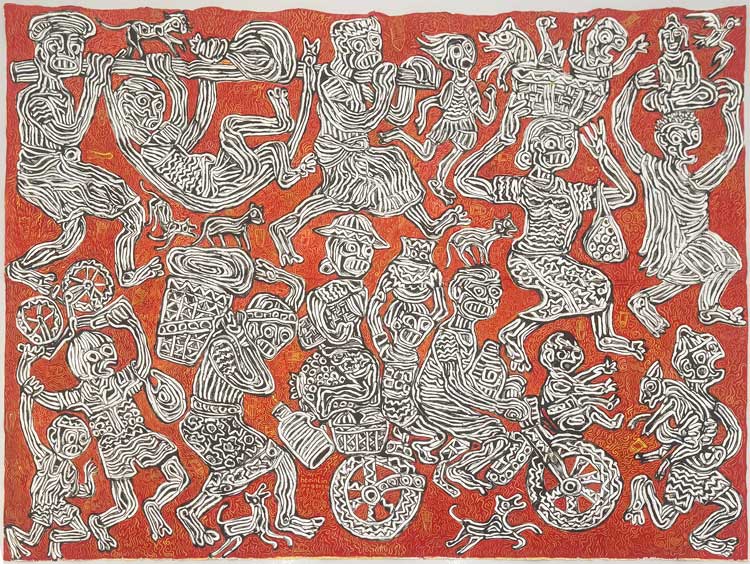

Htein Lin, Fiery Hell, 2024. Acrylic on canvas. © Courtesy the artist and Richard Koh Fine Art.

The most recent work in the exhibition is Fiery Hell (2024), which portrays the reality of present-day Myanmar, ravished by civil war since 2021 and with no end in sight. Reflecting the plight of rural communities, it depicts people with anguished faces as they flee burning villages, carrying their lives on their backs, including livestock, children and assorted possessions. The sinewy forms of Lin’s figures are distinctly rendered with finger painting, a technique that he developed while behind bars and used here to powerful effect. These are scenes that Lin has witnessed himself in Shan State, an area that has experienced widespread fighting, displacement, and humanitarian crises – troubles that have only been exacerbated by the recent earthquake that killed thousands and left many homeless.

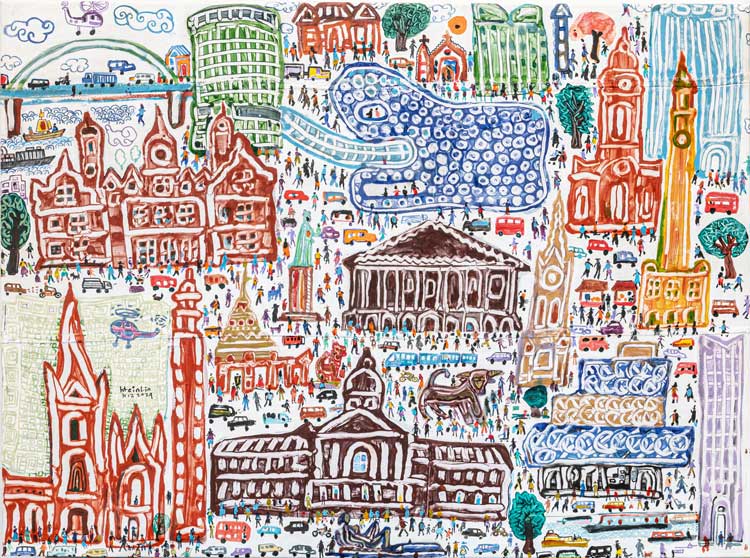

Htein Lin, How do you find Birmingham?, 2024. Acrylic on canvas. © Courtesy the artist.

Lin’s finger-painting technique is also used in the series How Do You Find …? (2006-), a charming body of paintings made in the context of freedom. Inspired by the friendly question from locals about his experience of living in the UK, these busy urban panoramas are characterised by their simple depictions of buildings and people. Bringing to mind the bustling street scenes of LS Lowry, the vibrant cityscape How Do You Find Birmingham? (2024) features many local landmarks including Birmingham library, the Bullring shopping centre and the Dhamma Talaka Peace Pagoda, the only Buddhist temple in Europe built in the traditional Burmese style. These are genteel and playful works, which lack the brutal, raw energy of Lin’s prison paintings. It is hard to believe they are by the same artist.

Despite all the tribulations Lin has experienced, he has stayed remarkably strong, enduring as an artist against extraordinary odds. His most affecting works are the products of struggle, specifically those made in defiance of oppression. They reveal the resilience of the human spirit and how art can become a means of resistance and survival, not just for Lin but for all those whose stories he tells.