National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin

10 April – 10 August 2025

by CELIA DELAHUNT

Histories of modernist art increasingly emphasise the networks and collaborations that underpinned this international phenomenon. Yet it is still refreshing to see an exhibition that foregrounds friendship, encouragement and common purpose in the interactions between modernist artists, rather than their emotional dramas or rivalries. This is the case in Mainie Jellett and Evie Hone: The Art of Friendship, which charts how these two artists developed a visual language of abstraction in Paris in the 1920s that continued to echo throughout their careers. As one of the show’s curator’s, Brendan Rooney, explains: “Their story is one of convergence and divergence over time, but it was a slow separation. And there are always these indications of their shared history, their shared experience in Paris.”

Having met at art school in London, Jellett (1897-1944) and Hone (1894-1955) went to Paris in the early 1920s and presented themselves at the studio of the abstract artist Albert Gleizes. They insisted he take them on as his students, refusing to take no for an answer when he tried to resist. Their impressive confidence bears itself out in the paintings we see in the first room of the show: in pursuit of “extreme cubism”, their works layered abstracted blocks of colour and linear contours, the picture plane flattened, splintered and shifting in paintings such as Hone’s 4 Elements (1924) and Jellett’s 6 Elements (1926). The pair worked to refine the principles of abstraction that Gleizes had begun to champion, and their subsequent closeness in style and technique can be seen in this initial space. “We were hoping that when people walked into this room, they couldn’t immediately tell who had painted what,” Rooney says. Yet on close inspection, the differences in handling and composition become clear. Jellett is more controlled and precise, while in works such as the undated Composition we see what Rooney calls Hone’s “more impulsive” tendency to go beyond the limitations of Gleizes’s approach by reworking parts of the canvas and disregarding concerns about cramped compositions.

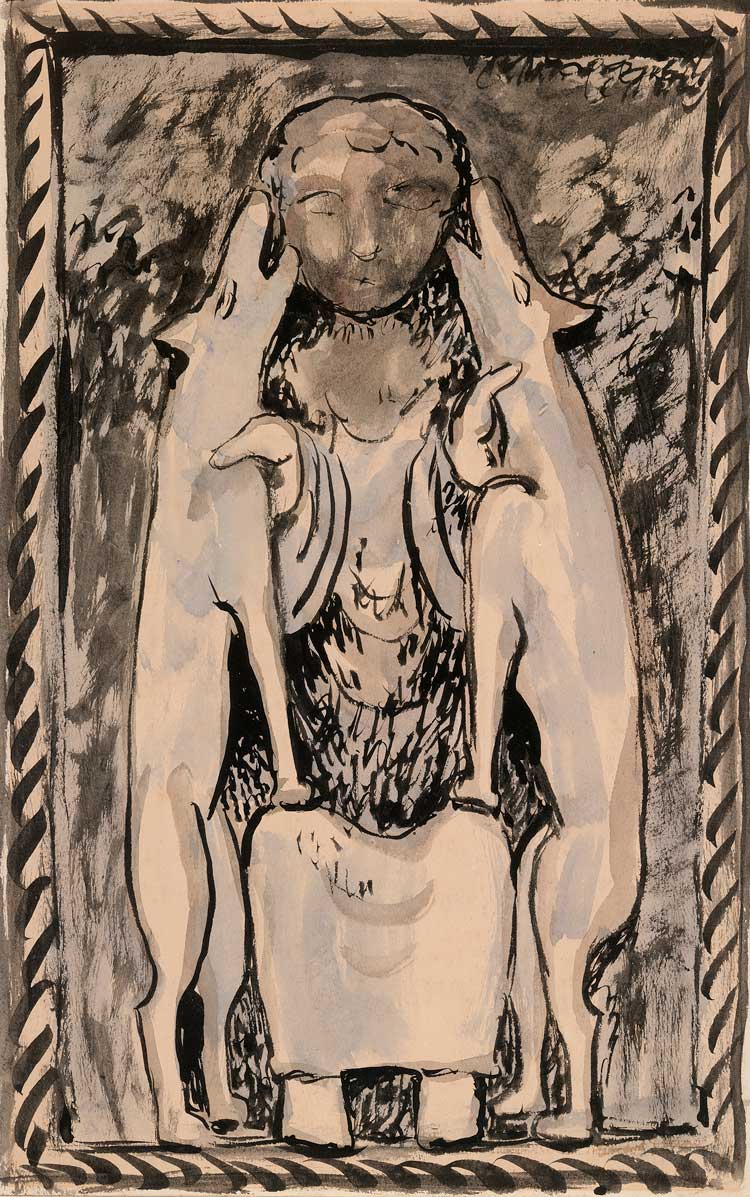

Evie Hone. Daniel in the Lions' Den, from the West Cross, Monasterboice Monastery, County Louth; Grazing Cattle (on verso), 1940s. Ink and watercolour on paper, 37 x 23.8 cm. © Geraldine Hone, Kate Hone and the FNCI. Photo, National Gallery of Ireland.

Jellett and Hone’s experiments in pure abstraction inevitably ran their course and, as the 1920s wore on, they began to introduce figuration into their work. This exhibition argues, however, that they never left abstraction behind. This is seen most strikingly in the works they made on religious subjects. A group of four depictions of the Madonna and Child made by Jellett between 1932 and 1940 highlight her use of this subject to reflect her own faith and to continue her experiments with colour, line, shape and composition. Presented together on one wall, they each appear as permutations of one another. Nearby, the influence of early Italian Renaissance painting is prominent in the cool tones and geometrically arranged forms of Hone’s Composition and Jellett’s Homage to Fra Angelico, both from 1928. Their interest in religious painting was not only grounded in their Catholic beliefs, nor was it solely a consequence of their knowledge of art history. It was born from the connection between spirituality and creativity that their work seemed to enshrine. As Rooney observes: “I think they probably had rather romanticised ideas – certainly Hone did – about the character of figures like Fra Angelico, who were unknowable because they were historical figures, but they wanted to know them. And I think Hone liked to believe that great art was made by great people, so she aspired to that herself, and they lived extremely dignified and upstanding lives themselves.”

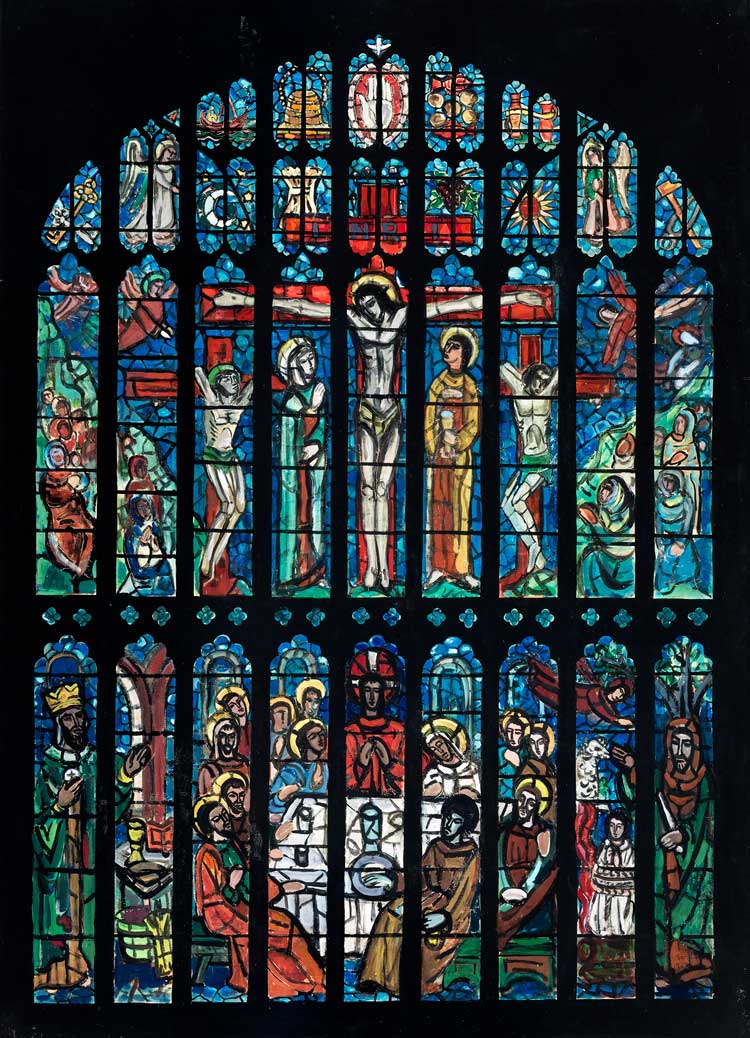

Evie Hone. The Crucifixion (top), Melchizedek, the Last Supper and the Sacrifice of Isaac (bottom), (for the East window, Eton College Chapel, Berkshire, 1952), 1950. © Geraldine Hone, Kate Hone and the FNCI. Photo, National Gallery of Ireland.

It is in Hone’s work in stained glass that we see the next manifestation of her earlier cubist practice. A whole room is devoted to these pieces, which glow beautifully from black walls, their luminosity emphasising the richness of their colour and the graphic boldness of their design. Hone carried out huge ecclesiastical commissions, for instance for the east window of Eton College Chapel, as well as some secular projects, and this range is represented here by preparatory works or small sections of the whole. An adjacent room reveals further divergences from painting that the two artists undertook, in textile, theatre and poster design. Influenced by the Paris-based textile artist Eileen Gray, the rugs and screen designed by Jellett, for instance, bear the cubist layering of forms and dotted, lined patterns seen in her Parisian paintings.

Evie Hone. Heads of Two Apostles, c1952. Stained glass, 86 x 61 cm. © Geraldine Hone, Kate Hone and the FNCI. Photo © National Gallery of Ireland.

Though each of the works is stunningly presented and carefully paired, it might have been interesting to see some archival material that brought the artists and their relationship to life. Without this, the exhibition feels like a very “art historical” presentation of two vibrant and creatively generous individuals, whose presence could have been conjured in greater detail as viewers moved through the show. Despite this, one of the strengths of this exhibition is its underplaying of questions of identity. Jellett and Hone were female Irish artists with deep faith, and Hone had suffered from polio which left her with physical challenges, including in one of her arms. These contextual details are interesting, and in places important, but they are not the main driver of the show. Rooney says: “We tried not to stress the Irishness, the religiosity, or the fact that they were women. They all informed the story, but you can fall very quickly into the trap of seeing it as ‘female art’, whatever that is – it doesn’t exist.” In this way, the art on the walls speaks for itself, its power retained in not being explained.

We see the importance of this in the last room, dedicated to the artists’ final years. In 1940, Jellett produced what is arguably a political work, The Land, Éire, not long after the 1937 ratification of the Bunreacht na hÉireann (Irish Constitution) that confirmed Éire as the newly independent state’s official name. Yet Jellett’s painting retains its commitment to abstraction above all else. While hinting at a pastoral beauty in the face of increasing industrialisation, it is first and foremost an exercise in the fluidity and modulation of colour and line.

Mainie Jellett. Achill Horses, 1941. Oil on canvas, 61 x 92 cm. Photo, National Gallery of Ireland.

Hone outlived Jellett by 11 years and her final decade saw her producing more traditional-looking sketches and paintings of the landscape surrounding her home in the Dublin countryside, as well as abroad. The sketches hang opposite Jellett’s The Land, Éire, next to the controlled yet curving lines of the horses and sea in Jellett’s Achill Horses (1941), and near to the jostling forms Hone presents in A Landscape with a Tree (1943). The collective effect is to offer a final comparison between the two artists and friends. They went their own ways in some respects after their time in Gleizes’s studio, pursuing new mediums and forms as the years passed, but in the end, they will always have Paris.

Evie Hone. A Landscape with a Tree, 1943. Oil on board, 69 x 69 cm. © Geraldine Hone, Kate Hone and the FNCI. Photo, National Gallery of Ireland.

Slavs and Tatars: The Contest of the Fruits

Rapping fruit, legendary birds and nail art feature in the UK debut of the Berlin-based collective S...

Liverpool Biennial 2025: Bedrock

From Sheila Hicks’s gemstone-like sculptures to Elizabeth Price’s video essay on modernist Catho...

Mikhail Karikis – interview: ‘What is the soundscape of the forthcomin...

Mikhail Karikis explains the ideas behind his new sound and video installation calling for action ag...

Art & the Book* and Spineless Wonders: The Power of Print Unbound**

Two concurrent exhibitions bring special collections into broader spaces of circulation, highlightin...

Focusing on the skills of wallpaper design and embroidery, this exhibition tells the story of the ...

Daphne Wright: Deep-Rooted Things

This show is a celebration of the domestic, and the poignant sculpture of Wright’s two sons, now o...

Anna Boghiguian: The Sunken Boat: A Glimpse into Past Histories

The venerable Egyptian Canadian installation artist Anna Boghiguian brings shipwrecks, shells and th...

Abstract Erotic: Louise Bourgeois, Eva Hesse, Alice Adams

A groundbreaking New York show from 1966 is brought back to life with the work of three women whose ...

Jeremy Deller – interview: ‘I’m not looking for the next thing. I...

How did he go from asking a brass band to play acid house to filming former miners re-enacting a sem...

Encounters: Giacometti x Huma Bhabha

The first of three exhibitions to position historic sculptures by Alberto Giacometti with new works ...

The Parisian scenes that Edward Burra is known for are joyful and sardonic, but his work depicting t...

The 36th Ljubljana Biennale of Graphic Arts: The Oracle

Surprising, thrilling, enchanting – under the artistic direction of Chus Martínez, the works in t...

It’s Terrible the Things I Have to Do to Be Me: On Femininity and Fame ...

In a series of essays about pairs of famous women, the cultural critic Philippa Snow explores the co...

Paul Thek: Seized by Joy. Paintings 1965-1988

A rare London show of elusive queer pioneer Paul Thek captures a quieter side of his unpredictable p...

This elegantly composed exhibition celebrates 25 years’ of awards to female artists by Anonymous W...

The first of its kind, this vast show is a stunning tour of the realism movement of the 1920s and 30...

Maggi Hambling: ‘The sea is sort of inside me now … [and] it’s as if...

Maggi Hambling’s new and highly personal installation, Time, in memory of her longtime partner, To...

Caspar Heinemann takes us on a deep, dark emotional dive with his nihilistic installation that refer...

Complex, multilayered paintings and sculptures reek of the dark histories of slavery and colonialism...

Shown in the context of the historic paintings of Dulwich Picture Gallery, Rachel Jones’s new pain...

William Mackrell – interview: ‘I have an interest in dissecting the my...

William Mackrell's work has included lighting 1,000 candles and getting two horses to pull a car. No...

Marina Tabassum – interview: ‘Architecture is my life and my lifestyle...

The award-winning Bangladeshi architect behind this year’s Serpentine Pavilion on why she has shun...

A cabinet of curiosities – inside the new V&A East Storehouse

Diller Scofidio + Renfro has turned the 2012 Olympics broadcasting centre into a sparkling repositor...

Plásmata 3: We’ve met before, haven’t we?

This nocturnal exhibition organised by the Onassis Foundation’s cultural platform transforms a pub...

Ruth Asawa: Retrospective / Wayne Thiebaud: Art Comes from Art / Walt Disn...

Three well-attended museum exhibitions in San Francisco flag a subtle shift from the current drumbea...

This dazzling exhibition on the centenary of John Singer Sargent’s death celebrates his versatile ...

Through film, sound and dance, Emma Critchley’s continuing investigative project takes audiences o...

Rijksakademie Open Studios: Nora Aurrekoetxea, AYO and Eniwaye Oluwaseyi

At the Rijksakademie’s annual Open Studios event during Amsterdam Art Week, we spoke to three arti...

AYO – interview: Rijksakademie Open Studios

AYO reflects on her upbringing and ancestry in Uganda from her current position as a resident of the...

Eniwaye Oluwaseyi – interview: Rijksakademie Open Studios

Eniwaye Oluwaseyi paints figures, including himself, friends and members of his family, within compo...