Franz von Stuck, Die Sünde (The Sin), c1912 (detail). Oil on canvas, 88 x 52.5 cm. © Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie / Andres Kilger.

Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin

23 June – 22 October 2023

by SABINE SCHERECK

When walking through the Berlinische Galerie in Berlin, the section about secession tells of Max Liebermann and Walter Leistikow and shows, among others, their impressionist paintings. In Munich, where the Lenbachhaus dedicates itself to the local art history, secession focuses on Franz von Stuck with his symbolist artwork. Mention the term secession in Vienna, and art historians will talk about Gustav Klimt and art nouveau.

Now the Alte Nationalgalerie in Berlin brings together these three variants, in its exhibition Secessions: Klimt, Stuck, Liebermann. With about 200 exhibits by 80 artists, it delves deep into these parallel movements, highlighting their common ground, the interaction between them and their differences. The show is a joint venture between the Alte Nationalgalerie in Berlin and the Wien Museum in Vienna, which is undergoing refurbishment. This now frees up more than a dozen Klimt paintings from its collection to star in Berlin. In May 2024, this exhibition will be shown in Vienna. However, it will not travel to Munich, where the secession movement in the German-speaking world first made headlines.

Dora Hitz, Cherry Harvest, before 1905. Oil on canvas, 160 x 232 cm. © Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie / Reinhard Saczevski.

There, in 1892, a circle of avant garde artists around Stuck shook the establishment, when splitting off from the Münchner Künstlergenossenschaft, the city’s long-standing society representing professional artists. It was also its sole society and hence symbolised the unity of the profession. The artists’ breakaway exposed its inner tensions. The press described it as the “Munich Secession”, a term the new group added to its name.

What had happened behind the scenes? The younger artists demanded quality instead of quantity: they wanted smaller exhibitions with fewer works so that their pieces would not go unnoticed in the mass-exhibitions displaying up to 2,000 paintings, which plastered exhibition walls from floor to ceiling – as was common practice at the time. They aimed for exhibitions featuring more contemporary, cutting-edge art, not crowd-pleasing and conventional styles favoured by the establishment. When their wish for reforms was refused, they went their own way to realise their vision of presenting art: only one row of paintings along a wall, enabling the viewer to take in the pictures bit by bit – the way visitors to exhibitions know it today.

Barred from showcasing their paintings in Munich, the secessionists took their work to Berlin, where it was well received. In 1894, the secessionists also presented their pieces in Vienna. The local progressive art scene was inspired by their determination to mount exhibitions themselves and take charge of their careers. In 1897, Viennese artists created their own secession group, when breaking away from their governing body, the Künstlerhaus. Among them was Klimt. Two years later, Berlin followed suit. However, there, a forerunner of the Berliner Secession, as it became known, had already been active since 1892. The artists’ collective Vereinigung der XI (Federation of the XI) was founded in reaction to the conservative Berliner Kunstverein, whose jury had refused to exhibit works reflecting new artistic trends, such as impressionism. Leistikow was a founding member of the Vereinigung der XI and was soon joined by Liebermann.

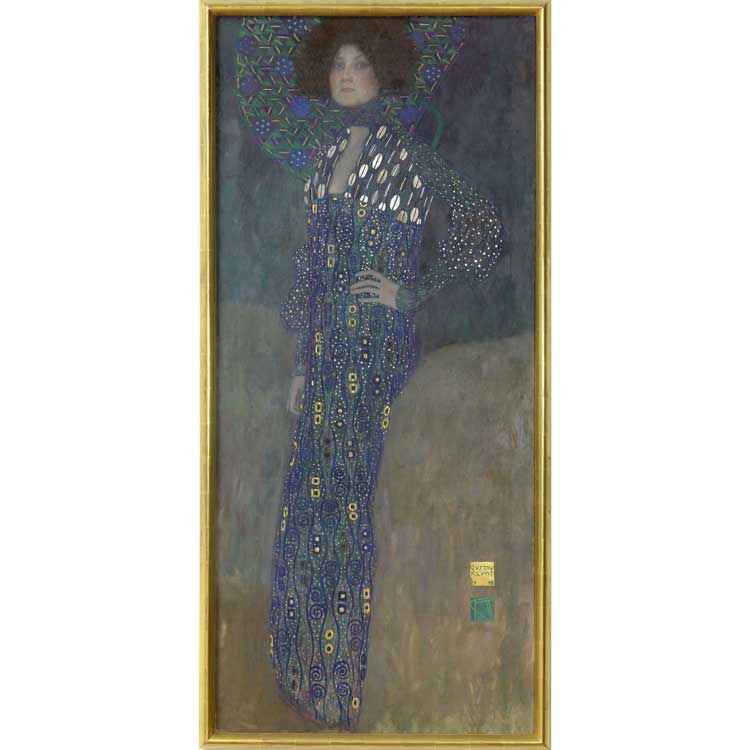

Gustav Klimt, Portrait of Emilie Louise Flöge, 1902. Oil on canvas, 184.3 x 86.6 cm, Wien Museum. © Birgit and Peter Kainz, Wien Museum.

At the Alte Nationalgalerie, the core space focuses on the works by Liebermann, Stuck and Klimt. There are the pieces that mark their signature styles such as Stuck’s symbolist The Sin (1893), Klimt’s Emilie Flöge (1902), classed as art nouveau, and Liebermann’s impressionist In the Tents (Catering Garden – Beer Garden in Leiden) (1900). More interesting, however, are the paintings that suggest how much the artists influenced each other, particularly Stuck and Klimt. For example, in their use of gold: in Stuck’s Orpheus and the Animals (1891), gold fills the background and Orpheus holds a lyre; and Klimt picks up both in Music (1895), creating a golden lyre. Both painters were also inspired by dancers, actresses and musicians. Liebermann, about 15 years older than his colleagues, in contrast, preferred to portray working people from poorer backgrounds. Here his Orphan Girls in Amsterdam (Study) (1876) is displayed. Later, he turned to the middle class enjoying their leisure time in parks. There is no gold in his colour palette.

Max Liebermann, In the Tents (Catering Garden – Beer Garden in Leiden), 1900. Oil on canvas, 51 x 76 cm. © bpk / Hamburger Kunsthalle / Elke Walford.

More striking are the landscapes and portraits, where the similarities between these three artists are a revelation. Stuck’s Trout Pond (1890) could, except for its dark tones, be mistaken for a work by Liebermann. Klimt’s Girl in the Foliage (1898) is reminiscent of female portraits by Liebermann. In Berlin, Klimt’s landscape paintings are less known, so this is a chance to discover a different side of him.

Apart from that, there are two major Klimt “exclusives” in Berlin: Serena Pulitzer Lederer, (1899) on loan from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, won’t travel to Vienna, and a collection of Klimt’s drawings, although coming from Vienna, won’t be displayed there. Instead, the drawings will return into storage as they are too delicate to expose them to light for long periods.

Maria Slavona, Houses at Montmartre, 1898. Oil on canvas, 116.5 x 81 cm. © Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie / Jörg P. Anders.

Surrounding the central space are smaller rooms covering the other 12 sections of the exhibition. Some reflect the themes the secessionists captured on canvas, such as high society, work and everyday life, encounters with nature, the intimate space and springtime. Others give an insight into the inner workings of the different secessions. They are the more captivating sections, as they unfold what it meant to be part of a secession movement. They also illustrate their activities and remind the visitor of their significance for today in paving the way for modernity.

Although nowadays the secessions of the different cities are often identified with the artistic style of their leading figures, each secession was in fact pluralistic and encouraged several avant garde styles alongside each other. Each group had different rules for their membership. Munich admitted painters, sculptors and those engaged in the applied arts; Vienna also included architects. Berlin was the most progressive one, being also open to women. Sabine Lepsius, Käthe Kollwitz, Dora Hitz, Julie Wolfthorn and Maria Slavona were among its members.

Thomas Theodor Heine, Poster for the 3rd exhibition of the Berlin Secession, 1901. Lithograph, 65.5 x 90 cm. © Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Kunstbibliothek. Photo: Dietmar Katz.

This aspect is poignantly demonstrated in Thomas Theodor Heine’s poster for the third exhibition of the Berliner Secession: it shows a woman with a wide dress, holding paintbrushes and a colour pallet while gently, but self-confidently kissing a bear, which symbolises Berlin. This is only one of many posters, which are very telling themselves. To assert their place in the art world, the artists marketed the secession as a brand, producing not only beautifully designed posters for their exhibitions but also postcards and letterheads.

For the poster advertising the first exhibition of Munich’s secessionists in their city in 1893, Stuck chose the head of Pallas Athena with a warrior helmet. She is the Greek goddess of wisdom, warfare and craft and thus symbolised the younger generation’s strife at the artistic forefront. She became the emblem for Munich’s secessionists. Klimt picked up the image of Pallas Athena when designing the poster for the first exhibition of the Viennese secessionists in 1897. Here now, a varied selection of posters provides a feel for the time. The ones by Alfred Roller and Koloman Moser stand out: partly for their sumptuous flowing art nouveau lines, partly for their modern straight lines and orange-brown colour scheme, nowadays associated with the 1970s.

Particularly precious in this show are the exhibits visitors usually do not get to see: the small catalogues, which accompanied the exhibitions staged by the secessionists. These were crucial for the curators of this exhibition, Ralph Gleis from the Alte Nationalgalerie in Berlin and Ursula Storch from the Wien Museum, as they made sure that all works presented now were part of the secessionists’ exhibitions back then.

To raise their profile, the secessionist groups also acted internationally, inviting the likes of Edvard Munch from Norway and Ferdinand Hodler from Switzerland. (Berliners were able to familiarise themselves with Hodler’s work when the Berlinische Galerie featured him in 2021. Later this year, the Berlinische Galerie will devote its space to Munch.)

For the chairmen of the secessionist groups, who decided which works would be exhibited, it was a fine balance between hosting international artists and promoting their own members. They couldn’t maintain this balance. It led to quarrels and artists leaving, especially when their cutting-edge work was rejected. They formed, among other groups, the New Secession. This separatist group also allowed into its ranks members of the artists collective Brücke, whose expressionist work was refused by the first generation of secessionists.

This present exhibition ends with the year 1913, when these new groups emerged in Berlin and Munich, although the story of the secessions continues for much longer. Sadly, these developments are not clearly explained in this exhibition. In Berlin, the secession comes to an end in 1937 under National Socialism. In Munich, it was revived after the war. And in Vienna, it still thrives following its motto “Der Zeit ihre Kunst, der Kunst ihre Freiheit” (Time its art, art its freedom) and showcases contemporary art in its purpose-built exhibition house, which dates back to the Viennese secession’s origins in 1897.