Oceanside Plaza, downtown Los Angeles, an abandoned luxury skyscraper development tagged with graffiti. Photo: Mario Tama/Getty Images.

by JILL SPALDING

Graffiti as first defined is as old as the impulse to leave a mark on the world. Before it came to mean “write”, the ancient Greek verb graphein meant “scratch, draw, paint”. Graffiti as we meet it today is more fluid, having evolved from a thought or identifier incised on a rock to a highly marketable art form.

To track its history, know how graffiti first presented. Too specific, Indonesia’s 51,000-year-old cave wall animals petitioning a good hunt and too transactional, Mesopotamia’s trade-centric cuneiform. Too systemised, the hieroglyphs carved by the ancient Egyptians into miniature murals, Imperial China’s 1,000 basic signs that were worked into the supreme art form of calligraphy, the precise Phoenician alphabet, and those 28 repeating signs forming the 3,000-year-old inscription on a stone found in Mexico.

Closer, the semi-abstract pictograms worked by the Yuan into a transgressive writing style, and the Arabic script developed from abstracted letterforms. Directly relevant, the roadside marks left by non-literate nomads, thought to be the first examples of spontaneous self-expression, and the ancient Greek and Roman messages scrawled on city walls by citizens and slaves seeking to communicate thoughts and post a visual autobiography. Although graffiti was illegal – deemed defacement and removed at the taxpayers’ expense – Pompeii, alone, has turned up more than 11,000 wall inscriptions, and down to our time no cities and few streets have been spared.

Poolside mural by French street artist Mr Brainwash, commissioned by the French consulate at the former home of Dean Martin, Los Angeles. Photo: Jill Spalding.

Currently heading the list are Paris, London, Melbourne and Berlin, but the first modern appearance of the raw, furtive, scrawl that Norman Mailer first called “graffiti” fully manifested in 1960s Manhattan. Immortalised by Magnum photographer Bruce Davidson, loose “crews” of taggers armed with spray cans “bombed” every surface of the subway cars, then fanned out all over the city, surreptitiously airbrushing entire buildings with coded names and wild images.

Parsing their styles is a challenging exercise. The aspirant starts out with tagging (name, initials, or logo in one colour) then perfects a throwup, or throwie (an outlined letter filled-in with colour). The letters range from wild style (a hard-to-read mishmash of arrows, curves and spikes) to blockbuster (blocky letters often painted with rollers to cover a large area fast) to bubbles (round, bloated, sometimes multicoloured and overlapping) and sharp (letters or elements rendered in angular forms). Highest-ranked is a “piece” or “character” – short for “masterpiece” (a big, complex free-hand wall painting that is time-consuming, difficult to execute, and characterised by a rich palette, 3D wizardry and writing that has been masterfully altered to skew the literal meaning). Stencil uses cutouts to transfer a reproducible design with spray or roll-on paint. The 2007 addition of “calligraffiti” (by the Dutch artist Niels “Shoe” Meulman), which combines calligraphy, typography and graffiti to take street aesthetics into museums and homes, may be the practice’s first fully recognised art form.

As rigorous as the Commandments, there are absolute rules: observe them to earn respect, or discard them at your peril. Never ask to join a crew – rather, earn an invitation by perfecting your technique. Do not mark-up memorials, private houses or functioning cars. Never bury a work by someone in the game longer or more accomplished than you, and know the hierarchy of what to paint over; throwies cover tags, pieces cover throwies, burners cover pieces. Painting over a deceased tagger is not a good look, and obliterating an RIP tribute earns total disrespect.

Such is the ranking but, until marketable, all graffiti was vulnerable. Dodging the law, taggers moved to Philadelphia where, to get his girlfriend’s attention, “Cornbread” (Darryl McCray) marked up her neighbourhood with “Cornbread Loves Cynthia”, then tagged the entire zoo with his name, which got him arrested.

The action moved down to Miami whose empty, windowless, warehouses in Wynwood’s rough garment district provided 300-plus taggers with an outdoor gallery for transgressive murals that documented the rich diversity of Miami’s cultural heritage and challenged social norms. They would become prime backdrops for photoshoots, and those by Zephyr, Maze, Mista One – and later, Ahol Sniffs Glue, Atomik, and Trek6 – are now landmarked, visited by more than three million locals, tourists and Miami Art Basel Fair groupies annually. At the time, though, with no money for good materials, and no way to market them, the murals were transitory, painted over by newcomers or fading to oblivion.

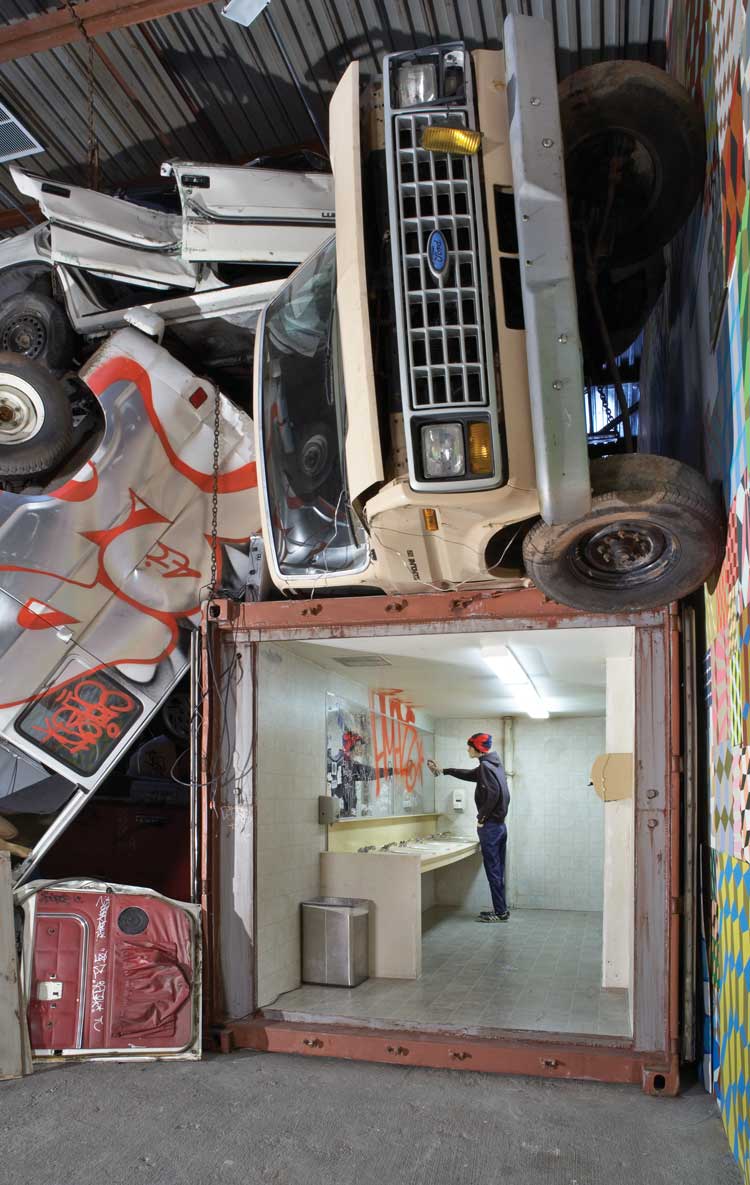

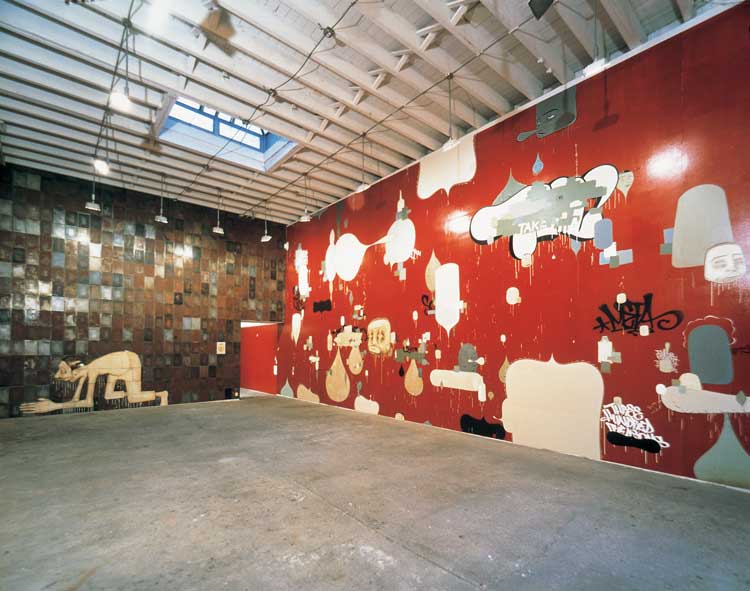

Barry McGee. One More Thing, 2005. Photo: Tom Powel Imaging. Courtesy of the artist and Jeffrey Deitch, New York.

Best for immortality to go the gallery route. Starting in the free-wheeling 70s when people didn't have to know art to understand mark-ups, and transgression in all forms was admired, graffiti came to be viewed as precocious, amusing, daring – even desirable – and visionary gallerists such as Jeffrey Deitch began representing the best. Lee Quiñones, Futura, Lady Pink and Dondi White became overnight stars, and the new art form, a movement. Hip-hop-raised tagger Fab 5 Freddy’s profile with a cameo in Blondie’s hit, Rapture, and a lyric by Debbie Harry, and Tony Shafrazi of the eponymous gallery came to fame for “bombing” Pablo Picasso’s Guernica, held a performative act that denied him admission to New York’s Museum of Modern Art for years but tagged him a folk hero.

Shepard Fairey. Mayday Mural, 2010. Houston Street and Bowery, New York. Photo: Jon Furlong. Courtesy of the artist and Jeffrey Deitch, New York.

Celebrity took over in the 1980s, when street artists were lured indoors to paint graffs on canvas for sale, positioning them to collectors as legitimate artists. In the 2000s, the new names to know were Swoon, Os Gemeos and Shepard Fairey. Icons such as Keith Haring made their way into catalogues, were sold for six figures, and resold for a profit. The day’s hottest collector’s item was a car spray-painted by Kenny Scharf; art star Andy Warhol invited self-taught “SAMO” (Jean-Michel Basquiat) to share his studio; and mega-collector Dakis Joannou had social activist Barry McGee (AKA Twist) paint a mural in his New York apartment.

Graffiti found a home out west more than a century ago, most fully in Los Angeles as a form of hobo art, carved with railway spikes on the walls of underground tunnels. As the city built out, taggers poured in, undeterred in their drive for self-expression and connection to an audience. Honing their skills to model the gritty urban subculture in ever more complex styles, they shifted in the public perception from vandals to artists.

In the 1970s a group of them, priced out of Venice and Hollywood, moved downtown, took over vacant warehouses, and opened avant garde galleries whose overnight success prompted a city-designated “Arts District”. Roughly bounded by Alameda, the Los Angeles River, the 101 Freeway and the 10 Freeway, it became the creative and cultural hub of Los Angeles – its world-class galleries a source for collectors – and fertile ground for home architect Frank Gehry’s first museum (MOCA) and grandest stage (the Disney Concert Hall).

.jpg)

Operation Under: Life Underground. Photo: Bill Dunleavy. Image courtesy Superchief Gallery, Los Angles.

Predictably, though, as the practice entrenched in the gang-ridden barrios, spray-bombing neighbourhoods struggling to gentrify, so, too, did the city’s conflicted relationship with graffiti. Depending on context and area, walls deemed defaced were cleaned up (at considerable cost to the taxpayer) while tourist attractions were spared. Still protected are the blocks-long murals fronting Venice Beach; the famed dreams-to-drugs Underpass Tunnel Murals, and any wall painted by Scharf or Fairey. Even in the Black and Latinx South Central and East Los Angeles barrios, where graffiti remains a felony incurring years of jail time, murals held masterworks have been not only spared but restored. Find there the famed Pope of Broadway portraying Anthony Quinn by Eloy Torez, Noni Olabisi’s traffic-stopping Freedom Won’t Wait and the Chicano “placas” – a rolling style of “barrio calligraphy” drawn from old English lettering.

Kenny Scharf, Go Wild, 2024. Installation view, Honor Fraser Gallery, Los Angeles. Photo: Jill Spalding.

The breakthrough in how the street viewed the street came about in 2012, when the Getty Research Institute commissioned 150 Los Angeles taggers to fashion a collaborative large-scale black-leather bound book, the so-called Getty Black Book, LA Liber Amicorum. Inspired by the early tradition of passing around a manuscript bound with blank leaves to fill with signatures, poetry and the expressive artistry of the time, the Getty’s “book of friends” would be marked up instead with the sort of graffiti written in the sketchbooks that taggers carried around and asked colleagues to “hit up” with their “pieces”. The resulting 143-page compendium of writing styles merges individual approaches to symbols, signs, letters and themes with techniques drawn from the Getty’s deep collection of Arabic calligraphy, pseudo-scientific phonetics, exotic Renaissance alphabets and – dearest to the curator – “Albrecht Dürer’s Introduction to Measurement, a demonstration of how the artistic imagination can transform line, circle and S-curve into complex illusions of three-dimensionality on a two-dimensional plane”. Co-curated by Axis, Cre8, Defer, EyeOne, Fish, and Miner, the collaborative composite of quirky letterforms crafted by subtracting through cutouts, or adding with stickers, board, foldouts or relief pigment, is impressive, but more of an exercise than a masterpiece because the artists were selected from hearsay, not street-cred, (thus including some lesser talents and such outliers as tattoo art); and “collaborative” proved a misnomer, since enemy crews refused to gather in the same room.

The effort mattered more as a storied institution’s elevation of taggers to artists. Know their names to know the breadth of LA’s graffiti-art community: Acme / Adict One / AiseBorn / Angst / Arbe / Asylm / Atlas / Augor / Augustine Kofie / Bash / Betoe / Big Sleeps / Biser / Blosm / Bob Roberts / Cab / Cache / Cale One / Care / Charlie Roberts / Chaz / Chris / Chelo / Chubbs / Crae & K4P Crew / Craola / Craze / Cre8 / Crime / Cryptik / Czer One / Defer /Demer One / Design9 / Devin Flynn (Elm) / Dr.Eye / Dsrup / Duem and Crae / Dye5 / Earn One / Eder / Elika / Else / Enk One / ESK31 /Estevan Oriol / Fearo / Fish /Gabe88 / Gajin Fujita / Gkae / Gorgs / Graff One / Gramps / Green / Haste / Heaven / Hert / Hex (LOD) / Hex (TGO) / Hyde / lK4P / Jack / Jake One / Jero and Each / Joker One / Kaos / Kasl/ Keo One / Kopey / Korea / Kost One / Kozem / Krenz (Yem) / Krush / Kwite One / Kyle / Kyote / Ler Keen / Look / Mach Five / Mandoe / Man One / Mike Miller /Mist / Mr. Huero / Noek / Notik / Nuke / OG Abel / Owen / P15 / Panic One / Patrick Martinez / P. Chuck / Petal1 / PetalBlosm / Phever / PJ /Playboy Eddie /Pletk P17 / Precise / Prime / Punk / Push / Pyro / Pyer / Rayo / Relic / Relm / Retna / Rev / Rich One / Rick Ordoñez / Risk /Rival / Roder 169 / Sacred 194 / Sano / Sel / Ser / Shandu One / Sherm / Skan One / Skez / Skill / Slick / SomeOne / Soon One / Spade / Spurn / Syte One / / Swank / Tanner / Teler / Test / Thel / Trigz / Tyke Witnes / Tempt / Thanks / The Phantom Street Artist / Useck / Val / Versus 269 / Vox One / Witnes / Werc / Wise / Wisk /Woier / Zes. To know the masters, though, memorize these: The Phantom Street Artist, Versus 269, Vyal, and Wram One.

Thinking to bring the work back to its roots, the El Segundo Museum of Art invited the same artists to mount the material on its walls for an experience (as its exhibitions are known) called SCRATCH. The recognition was viewed as historic, although, as faulted by the noted tagger Illescas, most were White or Hispanic whereas in the barrios, where tagging is still criminalised, punishment falls heaviest on young Black men. And none was female (even today, and even on the internet’s wide platform, female artists account for only 5% of transactions).

Middle America held back, but by 2010 graffiti was so gentrified on both coasts and abroad as to warrant exhibitions at New York’s Brooklyn Museum and, in Paris, at the prestigious Grand Palais and the Cartier Foundation. Five years later, in Manhattan, developers paid street artists $3,000 each to embellish the area around Vesey Street, and hired others to graff the metal sheds at the site of the September 11 attack – though more for promotion than tribute, since they came down a year later. That same year saw the ultimate crowning – in Miami, helmed by famed tagger Alan Ket, an official Museum of Graffiti, and in Los Angeles the fiercely exclusive Soho Warehouse, a reverse-chic outpost in the still scrappy Arts District, ornamented by 100-plus artists and a commanding mural by Fairey at the entry.

Mural by Eloy Torrez at Lula Cocina Mexicana, Los Angeles. Photo: Jill Spalding, courtesy Chuck Craig.

Lesser work, however, is still held a nuisance. With tagging begetting more tagging, last year in LA alone 175 designated cleaners, armed with blasters spraying 3,500lb of water per square inch, and working from cherry-picking trucks for multistorey splatters removed up to 7m sq ft of illegal spray paint. Full circle to the recent dust-up involving the billion-dollar Oceanside Plaza – a conglomerate of park, five-star hotel, high-end restaurants and retailers intended to gentrify a blighted Los Angeles neighbourhood that had stalled for lack of funding. Dozens of taggers moved in to “bomb” the 50-storey canvas of its luxury skyscrapers. Its admirers could not stop a removal that will cost the taxpayers $4m (£3m), but took comfort on learning that the scourge is now a tattoo, etched down the back of a fan by master tattooist Eric Reyna.

Enter the ultimate question; if 80 years ago, graffiti was just a subversive identifier born of the underground, what is it now? Words scrawled on canvas and framed? A tattoo written on human skin? An icon messaged like an emoji on the web? And if still limited to “scratch, draw, or paint”, does only quality distinguish graffiti from what we hold art?

More critically, if graffiti can be art, what art is it not? Although expertly patterned, it’s not related to Franz Kline’s housepainter-brushed graphic networks, nor to Jackson Pollock’s gestural expression, or Brice Marden’s intertwined webbing. Though still often built around words, it’s not Robert Indiana’s sculpted nouns, Lawrence Weiner’s stencilled koans, Jack Pierson’s fractured alphabet, Barbara Kruger’s aphoristic phrases, Ed Ruscha’s wry commentary, Mel Bochner’s spiralled synonyms, Tracey Emin’s neon sayings, Glenn Ligon’s social messaging, or Christopher Wool’s cryptic iconography.

Arguably, neither is street art brought indoors: the graphics of Haring, cleaned up for a retrospective that filled The Broad last year; the “outsider” paintings by Basquiat taking over the salesrooms; the street scrawls that Jenny Holzer exchanged for neon truisms; the spray-painted wall fragments that José Parlá now markets as sculpture, and the exuberant urban markups that Shinique Smith was asked to work into a monumental mosaic, Only Light, Only Love, for a Los Angeles Metro station.

Yet more removed, the furtive images by Banksy, so prized after the work he fashioned to explode sold for $25.4m that they rate their own (unsanctioned) museum, where adults are charged $30 and children $20 to see reproductions on distressed panels made to look like street walls, when the real version is available outside for free. Yet more anodyne, across nations, the work of street artists commissioned to glamorise storefronts and developments.

And there went the soul of graffiti. Storied Miami gallerist and artist Fredric Snitzer is appalled. The anger and urgency of an underground movement leached of power! The apocalypse monetised! Raw work by vandals prettied up! “They were street kids – gangsters and outlaws – risking their freedom, even their lives!” Those that Snitzer scooped up for the course he taught at New World School of the Arts – Alex Sweet, Loriel Beltrán and Michael Vasquez – were given free rein: they sold well, yet never lost their edge.

Barry McGee. The Buddy System, 1999. Photo: Tom Powel Imaging. Courtesy of the artist and Jeffrey Deitch, New York.

Ask graffiti historian and curator Roger Gastman and you’ll get an earful of what’s the real deal. Quality and craftsmanship matter little, and fame not at all. As originally conceived, graffiti should still startle and offend and retain the transgressive nature of a weed. Paramount, though, is respect on the street, earned if the tagger has paid his dues by working consistently and long in the field. The work needn’t be held art – though it will be if painted on canvas or a living room wall (say, by Kaws or McGee), or commissioned, (as was Elle Street Art’s 2,000 sq ft outdoor mural for Manhattan’s Hudson Yards), or exhibited (as were the maquettes and three sections of Judy Baca’s Great Wall of Los Angeles, shown earlier this year at both LACMA and Jeffrey Deitch.

Judith F Baca. The Great Wall of Los Angles, 2023. Photo: Joshua White. Courtesy of the artist and Jeffrey Deitch, Los Angeles.

Happily, all is not lost to retail. Retaining their wacky zest are Scharf’s 175-plus works recently presented at Honor Fraser as Go Wild! collectibles, and – scheduled at the Taylor Fine Art Gallery – the on-and-off-the-wall mark-ups that placed Toons One! in the Guinness Book of Records.

Toons One! Future. Part of the section painted for the Guinness World Record for the largest glow

in the dark painting, Soqr Park in Ras al Khaimah, UAE. Overall size 416.26 m² (4,480.58 ft²). Image courtesy the artist and Taylor Fine Art.

More debatable is how far graffiti’s platform can be stretched. What of video – street artist Diego Bergia’s elaborate Primary Invasion video games, whose objective is spray-painting, making graffiti the entire focus of his work? And – the ultimate question – what of the blockchain? If other forms of art can translate to non-fungible tokens (NFTs), why can’t street art? It can, is the overall consensus of artist and collector. The transfer need not be radical: Oshi, a street art-turned-NFT gallery in Melbourne, Australia, has an IRL location and a digital location on the blockchain; Meatballs, a Berlin-based NFT/web 3.0 platform, has a blockchain gallery for original work and replicas of graffiti on the city’s walls.

Not so fast, says the purist. Whereas an argument can be made for writing on the sky (viz Yves Klein), how tag on the ether? And how message protest on a virtual wall when biting at the cloud remains toothless? Surely, posting graffiti online (#streetartNFT) alters its very nature. Yet, a growing number of street artists, led by Greg Mike and Matt Gondek, convinced that the two communities share same renegade ideology, have made their way on to it with scans, photographs, and videos of their physical creations. Among those more accomplished with digital tools, KIWIE circled the globe making physical images of characters painted against local backgrounds, then partnered with Rarible to turn them into NFTs. Flipping the physical-to-digital script, Lushsux animates and photographs defaced NFT images to fashion into the memes that he then mints as original NFTs, and California artist yonmeister provides the collector who buys one of his Domes physical works with an NFT twin. Crowding the field, several digitally native organisations (cf Secret Walls) have been fast-tracking graffiti artists on to NFT marketing platforms such as SuperRare, Mintable, OpenSea and Foundation.

To what end, though, besides profit? Is minting eternity not the antithesis of the spray-canned “bomb” that begs erasure? How experience the tagger’s dart-in-and-out high in an Instagram gallery that establishes the artist for all time in the digital realm? And how can “graffiti” define digitally rendered graffs sold and traded on a “platform” (FreeStyle NFT), then – as reported in Forbes – exhibited in a virtual reality “museum” (Streeth).

Still, of the street artists I sampled who have joined the NFT ecosystem, few see the irony. Most think it conveys the street appeal of spontaneity and irreverence, enabling a hybrid crypto-graffiti that feels authentic. And all value it for providing higher prices, secure returns, and a safe space where graffiti is not only decriminalised, but embraced for its artistry, creativity and social worth.

More critically, might the web 3.0 provide the last defence against erasure in a quantum world? Given that the generative artists working today will be hailed tomorrow as the last tribe of artisanal coders who mined human digital creativity before the onset of AI, graffiti that takes up life on the blockchain may well prove immortal.

As for its home on the streets, unless deprived neighbourhoods go the way of the hoop skirt, graffiti will endure as long as the neglected walls of blighted city streets do.