Michael Werner Gallery, London

13 April – 15 May 2021

by JOE LLOYD

This is Arcadia, but not as we know it. Aktaion (Actaeon) (2020), the largest canvas in the exhibition of recent paintings by Markus Lüpertz (b1941, Bohemia), depicts one of the goriest passages from Ovid’s Metamorphosis. The hunter Actaeon, having stumbled on the goddess Diana’s secret bathing spot, has been transformed into a stag. Those familiar with Titian’s The Death of Actaeon (1559-75), housed a short stroll away at the National Gallery, will be well aware of what happens next. In Nicolas Poussin’s phrase: et in Arcadia ego.

Markus Lüpertz. Aktaion (Actaeon), 2020. Mixed media on canvas in artist’s frame, 74 3/4 x 141 3/4 in (190 x 360 cm). Courtesy Michael Werner Gallery, New York and London.

Lüpertz’s piece takes for its model not Titian, but the lesser-known Florentine painter Luca Penni, whose version is held in the Louvre. Penni was one of several painters who beatified the French royal Palace of Fontainebleau, and his rendition has a decorative stateliness. Lüpertz has lifted six of Penni’s figures, but roughened them up, translating their delicate bodies into dense, somewhat sculptural forms. Shorn of detail, Actaeon seems to buckle with primal fear. Lüpertz’s paint is assertive, almost pugnacious. Smears of it adorn the frame, as if they have leapt out.

Markus Lüpertz. Jasons Abschied (Jason’s Farewell), 2020. Mixed media on canvas in artist’s frame, 78 3/4 x 102 1/4 in (200 x 260 cm). Courtesy Michael Werner Gallery, New York and London.

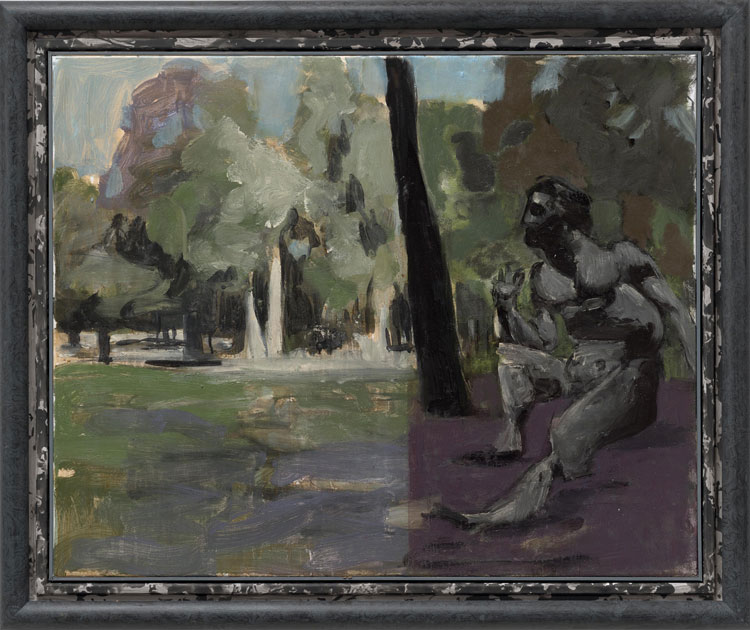

The painting’s fleshy colours are more muted than Penni’s, as though faded with age. This might reflect the fading of Lüpertz’s models from public consciousness. A second massive work, Jasons Abschied (Jason’s Farewell) (2020), adopts three figures from Luca Signorelli’s The Education of Pan (c1490), a painting that was destroyed in a fire in Berlin just days after Germany’s surrender in the second world war. Lüpertz has excised Pan altogether. One scene has become another. The central figure, now the hero, Jason, prepares to board the Argo. But instead of an ocean-going ship, he has a lakeside rowing boat.

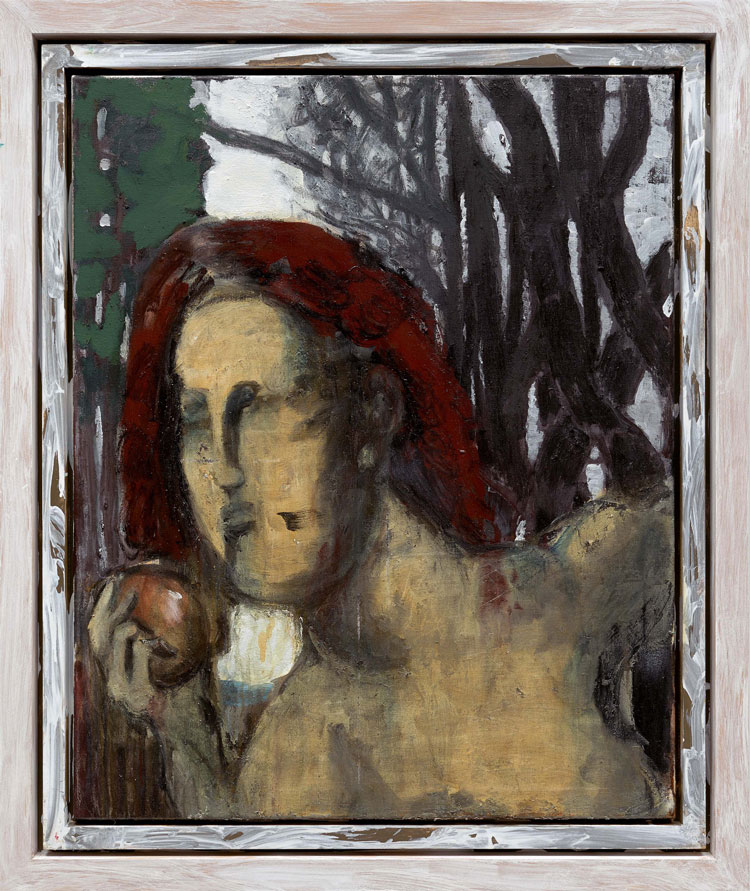

The same lake appears in Aktaion, as well as several of the exhibition’s smaller works, often (but not always) depicted as an unyielding rectangle of white. The classical Arcadia, like the region in the Peloponnese of the same name, was hilly and golden-hued. Lüpertz’s is palely lit and largely flat. One painting, Märkische Allee III (2017), features a road curving into the distance with the merest hint of a bump. Lüpertz’s landscapes are based on those that surround his studio in the March of Brandenburg, into which he brings characters classical and biblical, Arcadian and Edenic. An Eva (Märkisch) (2017) pulls the apple almost to her mouth, while a nude Nymphe Märkisch (2020) strokes her hair.

Markus Lüpertz. Eva (Märkisch) (Eve [Märkisch]), 2017. Mixed media on canvas in artist’s frame 39 1/4 x 32 in (100 x 81 cm). Courtesy Michael Werner Gallery, New York and London.

The Marches were historically viewed as an unpromising in-between land until it became reinvented as Prussia’s heartland in the late-19th century. Lüpertz sometimes seems like a monument from that earlier era. Always immaculately turned out, in a style that makes little concessions to the past 100 years, he cuts an intimidating figure. He publishes a “journal of diagonal thinking”, Frau und Hund. He was rector of the Düsseldorf Kunstakademie for two decades, during which he packed the faculty with esteemed fellow artists and emphasised traditional mediums. He has written at least two manifestos. All of which might imply a painter easier to respect than enjoy.

Markus Lüpertz. Nymphe Märkisch (Nymph Märkisch), 2020. Mixed media on cardboard in artist’s frame, 52 x 27 1/2 in (132 x 70 cm). Courtesy Michael Werner Gallery, New York and London.

Underpinning it all is an unshakable faith in the importance of art, by which he means painting and sculpture. Lüpertz appears to view less aesthetically pure tendencies with a fogeyish disdain. In a 2017 interview with Artnet, he said: “In this moment, we could all paint the greatest pictures, because we have unparalleled freedom. But nobody accepts it. Only us old sacks of shit live with it. But the youth isn’t interested. They ’d rather save the world from extinction, or stop the poles from melting — that ’s all nonsense.” There is surely a drollness here. But his exasperation with those who ignore the present’s unshackled painting rings clear.

Lüpertz belongs to a group of German artists, clustered around Michael Werner ’s first gallery in Cologne, who sought to revivify painting for the post-conceptual age. They faced a dilemma. The figurative tradition had been morally soiled by its associations with fascism, and figurative images had been rendered banal by mechanical reproduction. Abstraction had become inextricably bound with the US. To adopt it would be imitative at best, submission at worse.

Lüpertz’s solution to this problem drew on the seriality of cinema and animation. Early series turned Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck into frantic, unrecognisable whorls of paint. In 1962, he premiered his dithyrambic paintings. Named for the wild hymns sung by devotees of Dionysus – and revived by Friedrich Nietzsche – these interspersed figurative elements with blocks of abstract colour.

Through the decades since, Lüpertz has made a succession of volte-faces: a period focused on German motifs such as Wehrmacht helmets, flags and antlers; a passage of abstraction; an era devoted to reinterpreting art history; and a turn to landscape. But despite the variousness of his genres, the same pushes and pulls – abstract and figurative, pathetic and bathetic, severity and smirk – remain throughout. Recent retrospectives have turned to mash works together from throughout his career, a bewildering soup.

Markus Lüpertz. Adam, 2020. Mixed media on canvas in artist’s frame, 32 x 39 1/4 in (81 x 100 cm). Courtesy Michael Werner Gallery, New York and London.

In this context, Lüpertz’s turn to the Arcadian seem like the calm after the storm. The tone is at times pensive, though the forcefulness of Lüpertz’s technique remains. There are recurring forms, odd juxtapositions and odder severances. A second Jason (2020) is cleaved across four canvases. There are three paintings of Adam (all 2020), with a form borrowed from Jacopo della Quercia ’s bas-relief at San Petronio in Bologna. But Lüpertz has removed Della Quercia’s God, leaving the first man alone. His reach towards God becomes a hollow greeting to no -one.

Much in this work is inscrutable. “To introduce a sense of logical development,” writes the art historian Eric Darragon in the exhibition’s catalogue, “… is a vain enterprise. You come up against the artist’s own, very different kind of logic.” What remains clear throughout is Lüpertz’s prowess. The largest of the Adams sees its subject shrouded in darkness. A whitish line cuts through the scene, then links with a yellow path along painting’s lower rim, disconnected from the woodland above it. I admit I am not entirely sure what to make of these things. But the definition of Adam’s body within the shadows, the impress of light on the grass, the greyish green bunches of leaves in the trees above all speak to paint’s power to communicate.

The 36th Ljubljana Biennale of Graphic Arts: The Oracle

Surprising, thrilling, enchanting – under the artistic direction of Chus Martínez, the works in t...

It’s Terrible the Things I Have to Do to Be Me: On Femininity and Fame ...

In a series of essays about pairs of famous women, the cultural critic Philippa Snow explores the co...

Paul Thek: Seized by Joy. Paintings 1965-1988

A rare London show of elusive queer pioneer Paul Thek captures a quieter side of his unpredictable p...

This elegantly composed exhibition celebrates 25 years’ of awards to female artists by Anonymous W...

The first of its kind, this vast show is a stunning tour of the realism movement of the 1920s and 30...

Maggi Hambling: ‘The sea is sort of inside me now … [and] it’s as if...

Maggi Hambling’s new and highly personal installation, Time, in memory of her longtime partner, To...

Caspar Heinemann takes us on a deep, dark emotional dive with his nihilistic installation that refer...

Complex, multilayered paintings and sculptures reek of the dark histories of slavery and colonialism...

Shown in the context of the historic paintings of Dulwich Picture Gallery, Rachel Jones’s new pain...

William Mackrell – interview: ‘I have an interest in dissecting the my...

William Mackrell's work has included lighting 1,000 candles and getting two horses to pull a car. No...

Marina Tabassum – interview: ‘Architecture is my life and my lifestyle...

The award-winning Bangladeshi architect behind this year’s Serpentine Pavilion on why she has shun...

A cabinet of curiosities – inside the new V&A East Storehouse

Diller Scofidio + Renfro has turned the 2012 Olympics broadcasting centre into a sparkling repositor...

Plásmata 3: We’ve met before, haven’t we?

This nocturnal exhibition organised by the Onassis Foundation’s cultural platform transforms a pub...

Ruth Asawa: Retrospective / Wayne Thiebaud: Art Comes from Art / Walt Disn...

Three well-attended museum exhibitions in San Francisco flag a subtle shift from the current drumbea...

This dazzling exhibition on the centenary of John Singer Sargent’s death celebrates his versatile ...

Through film, sound and dance, Emma Critchley’s continuing investigative project takes audiences o...

Rijksakademie Open Studios: Nora Aurrekoetxea, AYO and Eniwaye Oluwaseyi

At the Rijksakademie’s annual Open Studios event during Amsterdam Art Week, we spoke to three arti...

AYO – interview: Rijksakademie Open Studios

AYO reflects on her upbringing and ancestry in Uganda from her current position as a resident of the...

Eniwaye Oluwaseyi – interview: Rijksakademie Open Studios

Eniwaye Oluwaseyi paints figures, including himself, friends and members of his family, within compo...

Nora Aurrekoetxea – interview: Rijksakademie Open Studios

Nora Aurrekoetxea focuses on her home in Amsterdam, disorienting domestic architecture to ask us to ...

Kiki Smith – interview: ‘Artists are always trying to reveal themselve...

Known for her tapestries, body parts and folkloric motifs, Kiki Smith talks about meaning, process, ...

Frank Auerbach, Britain’s greatest postwar painter, has a belated German homecoming, which capture...

How Painting Happens (and why it matters) – book review

Martin Gayford’s engrossing book is a goldmine of quotes, anecdotes and insights, from why Van Gog...

Jonathan Baldock – interview: ‘Weird is a word that’s often used to...

As a Noah’s ark of his non-binary stuffed toys goes on show at Jupiter Artland, Jonathan Baldock t...

Helen Chadwick: Life Pleasures

Helen Chadwick’s unwillingness to accept any binary division of the world allowed her to radically...

Catharsis: A Grief Drawn Out – book review

To what extent can the visual language of grief be translated? Janet McKenzie looks back over 20 yea...

Radical Software: Women, Art & Computing 1960-1991

With more than 100 works by 50 artists, this show examines the pioneering role of women in computer ...

Dame Jillian Sackler, the art lover and philanthropist, has died aged 84...

Giuseppe Penone: Thoughts in the Roots

With numerous works created with the twigs, leaves, roots, branches and majestic forms of trees, thi...

Solange Pessoa: Pilgrim Fields

An olfactory orgy of marigolds, chamomile, grasses, sheepskins and kelp is arranged into a surreal l...