© Hamish Fulton 2019. Courtesy Parafin, London. Photo: Peter Mallet.

Parafin, London

22 November 2019 – 8 February 2020

by BETH WILLIAMSON

Entering the quiet spaces of Parafin gallery just off London’s busy Oxford Street is always a pleasant experience and never more so than when viewing work by artist Hamish Fulton (b1946) in his exhibition A Decision to Choose Only Walking. Fulton came to prominence in the late 1960s and early 70s when the conceptual nature of his work, where the idea is key and the material object secondary, positioned him alongside other British artists of his generation such as Richard Long, Gilbert & George and Art & Language. Still, it is often the material object we come to see and Parafin is a small space, so to accommodate the range of Fulton’s practice with pieces from 1973 to the present day is a challenge. To accommodate large-scale wall texts is doubly challenging, especially when the exhibition’s starting point World Within a World, Duncansby Head to Lands End, Scotland Wales England 1973 (1973) is 6 metres (20 feet) across.

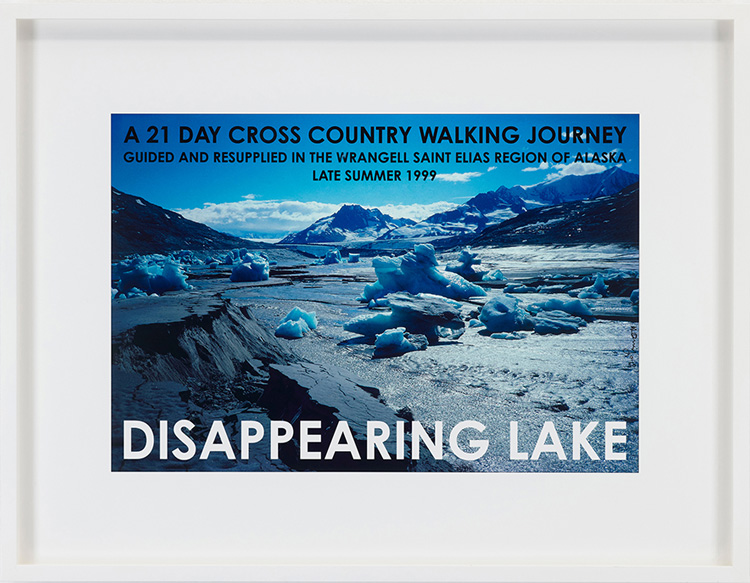

Hamish Fulton. Disappearing Lake, Alaska, 1999, 1999. Framed archival inkjet print, 45 × 58 cm. © Hamish Fulton. Courtesy Parafin, London. Photo: Peter Mallet.

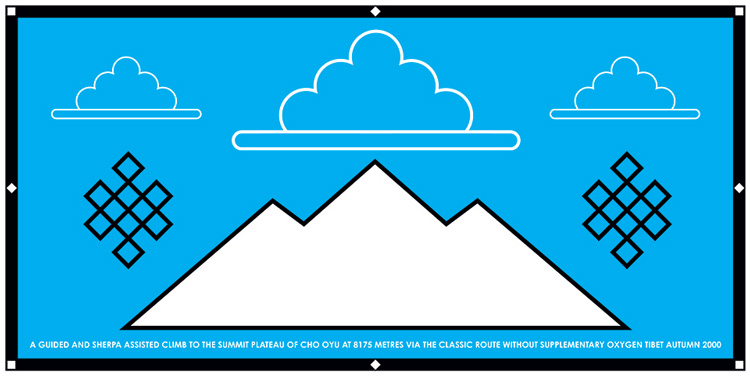

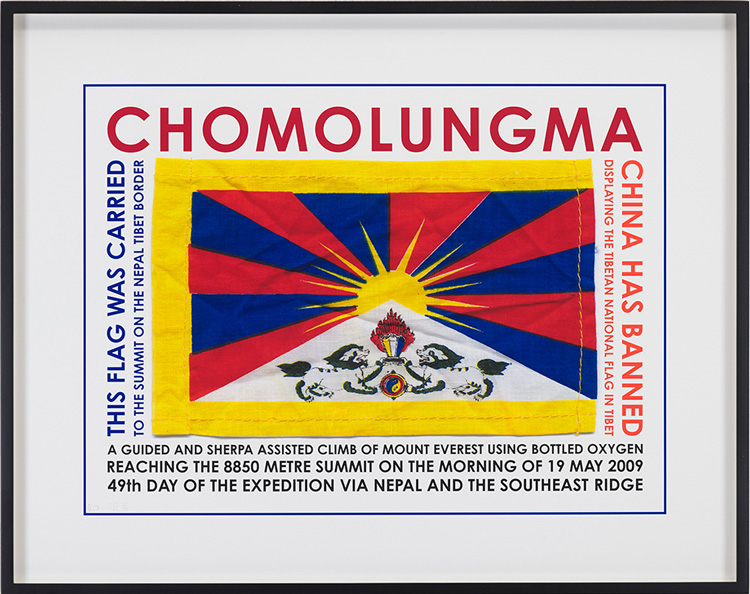

Walking is Fulton’s medium and he has been committed to its importance as an aesthetic medium for decades. He is not concerned with walking for its artistic resonances alone, but regards the importance of walking as widely as its many functions as a mode of transport, a means of protest, a way of linking communities and as a spiritual tool. His engagement with walking as an artistic practice has resulted in a body of work that not only traces individual walks that he has undertaken, but underlines pressing political and environmental questions raised by particular geographies. This means that many of the works he makes record something of walks that are significant for the natural environment – Disappearing Lake, Alaska, 1999 (1999) is just one example. Often the works coincide with the key political issues for the country in which they take place. China’s occupation of Tibet is a political cause that seems to have become more and more urgent for Fulton as time goes on. There is the large wall text Cho Oyu, Tibet, 2000 (2000), but other works, such as Chomolungma (The Tibetan National Flag), Nepal, 2009 (2009) and Google Champa Tenzin, Tibet, 2007 (2007), highlight his continuing concern with Tibet.

Hamish Fulton. Cho Oyu, Tibet, 2000, 2000. Wall text. Vinyl on paint, dimensions variable. © Hamish Fulton. Courtesy Parafin, London. Photo: Peter Mallet.

The range of materials used is considerable. Fulton uses photography, printing, wall painting and what he calls “walk texts on wood”. The latter are a delight and feature extensively in what amounts to a wall installation of 16 small works including the two most chronologically disparate in this group – A 19 Day Coast to Coast Walk Across Honshu, Ontake Summit Fuji Summit, Japan, Summer 1988 (1988) and A 21 Day Walk Via the Tops of Seven Small Mountains, 21

Hamish Fulton. Chomolungma (The Tibetan National Flag),

Nepal, 2009, 2009. Framed archival inkjet print, 59.5 × 75 cm . © Hamish Fulton. Courtesy Parafin, London. Photo: Peter Mallet.

Nights Camping, A Full Moon on the Seventh Night, Wind River Range, Wyoming USA, Late Summer 2017 (2017). Fulton has said that he builds experiences not sculpture and, in that respect, this grouping of smaller works is particularly effective, giving a sense of walking through different landscapes as you move along the roughly four-metre span of the display. This is important, as Fulton is clear that the walks themselves are the artwork and the exhibited objects are simply evidence of that. To curate a display that gestures towards that experience of walking is difficult, to achieve it is commendable. I particularly appreciate the work Mountain Skyline. 28 Pieces of Wood for a 28 Day Walking Expedition in Nepal, from Jomson to Hilsa, Autumn 2011 (2011) which is cleverly positioned like a mountain ridge with 10 smaller works below, the foothills of Fulton’s walks perhaps.

Hamish Fulton. Mountain Skyline. 28 Pieces Of Wood For A 28 Day Walking Expedition In Nepal, From Jomson To Hilsa, Autumn 2011, 2011. Walk text on wood, 50 × 343 cm. © Hamish Fulton. Courtesy Parafin, London. Photo: Peter Mallet.

In the lower floor gallery, Fulton’s work takes a different tone. All the images here are either photographic or archival ink-jet prints made between 2009 and 2017. Geographically, they range from locations in Iceland, Tibet, Nepal and Wyoming, US, to Wales, England and the Cairngorms in Scotland. There is a sense of calm and reflection in this small space as Fulton’s work presents the natural world in all its variety. The presence here of five images made while Fulton was walking in the harsh environment of the Cairngorms simply acts to underline the difference between that experience and looking at images such as these in a gallery. Fulton adds nothing to the landscape in which he walks and takes nothing away. If we take anything from these images, it is surely the sharp disconnect between where we are and what we are looking at and what we imagine Fulton’s experience might have been.

Hamish Fulton. Revisiting The Boulders, Jotunheimen, Norway, 2018, 2018. Wall text. Vinyl on paint, dimensions variable. © Hamish Fulton. Courtesy Parafin, London. Photo: Peter Mallet.

A 14-page booklet by Fulton, Words from Walks (2019), is freely available at the exhibition and gives a genuine insight into his thinking about walking. Here, he writes about the aesthetic and psychological qualities of walking and its rhythm. He also writes about the seasons of the year, the weather, the natural landscape and wildlife. One of his ideas that caught my attention is that of the cumulative experience of his walks: “My walks collectively constitute ‘a journey’. I am the storehouse of my walks. The satisfaction from earlier walks contributing on reflection, to the appreciation of present-day walks.” It strikes me that this is not unlike the cumulative experience of visiting exhibitions, as our experience of one artwork inflects our experience and appreciation of another.

Fulton has said that his artworks provide “facts for the walker [himself] and fictions for everyone else”. Of course, as viewers we all have individual responses to artworks. Those responses depend partly on our own personal context and on the context in which we view the works. At Parafin, enormous vinyl works such as Cho Oyu, Tibet, 2000 (2000) and Revisiting the Boulders, Jotunheimen, Norway, 2018 (2018) are really too large for the space. There simply is not room to step back and appreciate them properly. That said, the exhibition in its entirety is a breath of fresh air in the centre of London. It makes a journey to hills and mountains feel urgent and it inspires walking for its own sake.