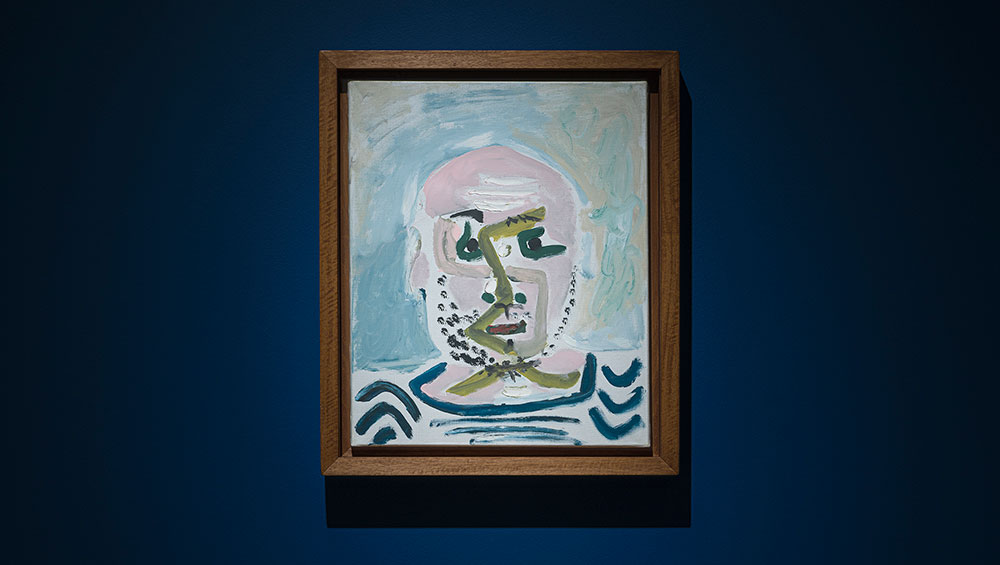

Installation view, Picasso – The Code of Painting, PoMo, Trondheim, 2025. © Photo: Uli Holz / PoMo, Trondheim. © Succession Pablo Picasso / BONO, Oslo 2025.

PoMo, Trondheim

1 August – 26 October 2025

by VERONICA SIMPSON

There is so much about Trondheim to admire. Here is a city of 212,600 that is blessed with a stunning, coastal location, a populace that seems content and well looked-after, and five high-class cultural institutions clustered in its centre – six if you count a newly refurbished theatre.

The calibre of the newest art institution, PoMo, is a case in point. Tastefully repurposing a turn of the 20th century post office (the Posten Moderne, from which the new museum takes its name), the Iranian French architect and designer India Mahdavi, with the Norwegian architect Erik Langdalen, has transformed this five-storey landmark into a sumptuous setting for any cultural experience.

PoMo, Trondheim 2025. © India Mahdavi, Paris / Erik Langdalen Arkitektkontor, Oslo. Ugo Rondinone, our magic hour, 2003. PoMo Collection. © Ugo Rondinone. Photo: Valérie Sadoun.

The duo have thoughtfully preserved the scale and decorative details of the original art deco building by the Norwegian architect Karl Norum, whose buildings are dotted all over Trondheim. Thus, the crisp white arches and decorated pillars of its lofty entrance hall have stayed, for instance, but there are added contemporary enrichments, such as a cosy reading room in the roof – all soft, green sofas, bespoke carpets and walls painted by the Dutch artist duo FreelingWaters with scenes of local flora and fauna in soft pinks and forest greens. Even its basement is a standout space: metal cabinetry and wall panels are interspersed with glowing alcoves featuring pale, timber lockers and cloakrooms, while its unisex bathroom walls are clad with rippling, reflective tiles more reminiscent of a Milanese nightclub than a small city art gallery. It is no surprise to learn this basement, the obvious location for film and audiovisual work, has been designed to double up as a bar and DJ space for events and openings. The uniting element for all these floors is Mahdavi’s eye-popping, mango-coloured curving steel staircase.

Staircase, PoMo, Trondheim 2025. © India Mahdavi, Paris / Erik Langdalen Arkitektkontor, Oslo. Photo: Valérie Sadoun.

Behind this new contemporary art space are the Reitan family, who made their money from retail and property. But why does Trondheim need another visual art museum when it already has four? According to PoMo’s director, Marit Album Kvernmo, they all play their part in the cultural ecosystem: the Kunstmuseum is the main regional public art museum, with an important but largely historical collection. The Kunsthall is a public contemporary art museum, with an international focus, and a dedication to mid-career artists. The National Museum of Decorative Arts (Nordenfjeldske Kunstindustrimuseum) is exactly what it claims to be, and also holds the Hannah Ryggen collection and the stewardship of the Hannah Ryggen Triennial. (Ryggen, a groundbreaking textile artist was hugely celebrated in her lifetime, with one of her compelling, feminist works shown alongside Picasso’s Guernica, when it visited Norway). The KUK (Kjøpmannsgata Ung Kunst), which like PoMo is a private gallery, focuses on emerging artists. PoMo’s remit is contemporary and international, but with a collection skewed towards female artists – to start redressing historical imbalances, it is aiming for a 60/40 bias in its slowly expanding collection.

Reading room/study, PoMo, Trondheim 2025. © India Mahdavi, Paris / Erik Langdalen Arkitektkontor, Oslo. Photo: Valérie Sadoun.

As the location of Norway’s largest university, Trondehim is a big student city, but the Reitan family seem intent on driving the cultural agenda to enrich the intellectual and artistic ecosystem for all residents and visitors. They own the five-star Britannia hotel, and have refurbished and reinstated the Nye Hjorten theatre, which neighbours their new museum, and are going to great lengths to establish a programme of festivals, events and activities around this new cultural quarter that will give affluent, culture-loving Norwegians and international tourists every reason to make Trondheim a regular destination.

PoMo opened in February with Postcards from the Future, a collection show. The collection is small (about 30 works) but interesting, with examples by Franz West, Philippe Parreno and Katharina Fritsch on permanent display, and the show attracted more than 60,000 visitors.

Main hall with several works by Franz West. PoMo, Trondheim 2025. © India Mahdavi, Paris / Erik Langdalen Arkitektkontor, Oslo. Photo: Valérie Sadoun.

But the current offering is the show that will grab the wider art world’s attention. Pablo Picasso: the Code of Painting showcases 50 of the artist’s works from 1961 until his death in 1973. These late works, say the curators, Dieter Buchhart and Anna Karina Hofbauer, were widely criticised before and after his death. It was in 1961 that Picasso married his second wife, Jacqueline Roque – the last in a long string of much younger female companions – and retreated to a spacious countryside villa in Mougins. He was incredibly productive during this late period, with 3,100 works, often dashing off several in one day and many with a sketchy, spontaneous feel. Until recently, their quality has been widely contested. John Berger, in his 1965 book The Success and Failure of Picasso, dismissed these later works declaring Picasso to be “the kind of extrovert artist (who) needs big themes”. Even the art historian Douglas Cooper, Picasso’s so-called friend and a collector of his art, described the work from this time as “incoherent doodles done by a frenetic dotard in the anteroom of death”.

Buchhart and Hofbauer have long felt this era needed a reappraisal. The former talks of there being “so much energy in the work”, such “vitality, spontaneity”. Some might say the sketchiest works are bound to feel spontaneous, given how little time was spent in their execution. The show’s title is taken from social scientist Claude Lévi-Strauss’s comment on the self-referentiality of Picasso’s later work: “It is an oeuvre that not so much conveys an original message as devoting itself to a pulverization of the code of painting.”

Pablo Picasso, Tête de femme au chapeau (Head of a Woman with a Hat), Mougins, 7 July 1971. Fundación Almine y Bernard Ruiz-Picasso, Madrid. © FABA Photo : Hugard & Vanoverschelde. © Succession Pablo Picasso / BONO, Oslo 2025.

Certainly, there is an argument that the restless churning out of these often-sketchy works is Picasso experimenting, a way of decoding, dismantling, taking apart the idea of what a painting is. But does it arrive at somewhere new? It’s always hard to see the influences and inspirations in an artist’s later work if you have grown up with it – certainly Jean-Michel Basquiat, George Condo and Dana Schutz have declared the fluency and lack of formality in these works to be a source of inspiration. Either way, the curators are calling it a “milestone exhibition”, which is no doubt music to the ears of any collector of late Picassos, and to their close collaborator for this show, the Fundación Almine y Bernard Ruiz-Picasso.

Pablo Picasso, Couple, Mougins, 1970-1971. Musée national Picasso-Paris. Jacqueline Picasso gift in lieu, 1990. © GrandPalaisRmm (Musée national Pablo Picasso) / Adrien Didierjean. © Succession Pablo Picasso / BONO, Oslo 2025.

If Berger felt Picasso was in need of some themes, the curators have done their best to provide them, although they are not so much themes as topics, including: self-portraits; painter and model; nudes; heads: deconstructing, reconstructing; encounters; musketeers; and night scenes. Some of the “themes” seem rather spurious, lacking a body of work to justify them as such. Night scenes, for example, comprises two works painted in tones of blue, purple and white, seemingly at night. But they are not particularly noteworthy in any other respect. One so-called theme seems to be pushing its luck to find relevance today: gender fluidity. There are just three paintings, one of which blends a male face with a female one; another, titled Couple (1970-71), a mishmash of male and female body parts. There even seems to be a claim that Picasso invented the emoji. A selection of Picasso’s pertly illustrated plates – all quirky facial expressions – has been titled: Universal language: the emojis. But these are the same expressions or gestures that every two-year-old draws when they start representing faces. Picasso is not the inventor, however quirky or characterful his might be.

Together with exhibition designer, Cécile Degos, the curators have devised a distinctive room palette of mostly white, counterpointed with strong blues, greens, ochres and reds – the feature colours of Picasso’s later works – to highlight the emotions and atmospheres present in each grouping.

The first room of late works is a deep, blue room, titled Self-Portraits. Indeed, there is plenty of playfulness and spontaneity in these portraits. Though he apparently declared, in 1918, that he would never bother with a self-portrait again, he is clearly present in most of them and having fun with his self-representation. One is a very Picasso-esqe, cubist-era disarrangement of perspectives – a sideways-on nose and eye, with a full-frontal eye wedged alongside. Another, Tete d’Homme (Head of a Man), Mougins, 16 February 1965, is surprisingly orthodox: symmetrical and directly representational. The closest thing to a completed painting in this group, despite its improvisatory execution in oil on plywood, I like this one best. There is an essential vigour and authenticity in the black lines that delineate mouth, nose and eyebrows, anchoring the explosion of unlikely colours around them – squiggles of white across the forehead, clouds of greenish grey (snot green?) across the right cheek. Light and shade are conjured with thick stripes of ochre, red and deep green. And yet it is manifestly human and present. Whether it’s a self-portrait is disputable.

Self portraits room, Picasso – The Code of Painting, installation view, PoMo, Trondheim, 2025. Photo: Uli Holz / PoMo, Trondheim. © Succession Pablo Picasso / BONO, Oslo 2025.

The rest are much more disassembled, minimal. The greens, ochres and reds reappear but like semaphore signals, coat-hanger outlines giving the barest indication of form. Lastly, a balding, grey-bearded man in Breton stripes with a wide, zigzag of snot green to structure his face. It is undoubtedly Picasso. But a great work?

And this is always the problem with an artist who has become so celebrated – and so lucrative. Even in his lifetime, he knew that a scribble on a napkin, dashed off over lunch, would have enormous currency. Several times while exploring this show, I found myself asking: if I didn’t know these were by Picasso, would I think the images were good enough to fill the walls of a major art gallery? That thought certainly popped up while looking at his pictures inspired by musketeers, apparently sparked by his watching films and series about the swashbuckling adventurers, popular on French TV in the 60s.

Picasso’s nudes are a more substantial offering, to be found in an adjacent room. Again, compared to earlier nudes – especially the violent, angular expressiveness of some of his Dora Maar nudes, or the wild, celebratory sensuality of his portraits of Marie-Thérèse Walters (whom he seduced when she was 17 and he was married to his first wife, Olga Khoklova) – these are not of the same calibre. But they do have their own bleak intensity. Sidestepping issues of his predatory and bullying behaviour around women (well documented in the BBC series Picasso: The Beauty and the Beast, an edited episode of which is broadcast on a screen in the show), the wall text states: “He used mainly female figures to explore personal struggles tied to eroticism and vulnerability, seen through the eyes of the ageing artist.”

Pablo Picasso, Homme à la pipe (Man with a Pipe), 1968. Courtesy of the Masterworks Foundation. © Photo: Dan Jackson. © Succession Pablo Picasso / BONO, Oslo 2025.

The first figure is troubling. In Nu Couché (Reclining Nude) from 1967, the sex of the woman (presumably Jacqueline) is represented as just a slit in the centre, a dark and cavernous blob below it (the – empty – womb?), with two enormous feet foregrounded (are they pushing him away?), two hands outstretched (likewise), two smallish breasts and a face turned aside. This does not signal lust, sensuality or even permission. I found no beauty, vitality or seduction in these nudes. Next to Nu Couché is Nu Assis (Seated Nude, Mougins, 17 December 1964) in which, again, a hair-sprinkled slit and a face are the dominant elements. One half of the body is roughly outlined in reddish paint, the other green. Almost half the canvas is left empty, unpainted. A more monochrome one (dated 21.10.67) seems like an evolution of the first, but is even bleaker and more joyless.

The painting at the far side of the room, Nu Allongé (Outstretched Nude, 1971) is a collapsed figure: collapsing arms, face, breasts, shoulders and a drooping mouth, the sex, a lustless aperture. These seem like the angry or frustrated articulations of a man who has lost interest in sex – lashing out at this lack of appetite, or perhaps aptitude.

Continuing around the room, we come to another Nu Assis (Seated Nude), this one from 1960. This is the kind of painting you would make after a dreadful night, a terrible row. The face and the sitter’s environment are clouded by a pall of dark grey, the body the red of dried blood, the bed a sickly green.

Only two paintings by the door reaffirm some kind of life or joy in the act, or in the sitter. Nu Assis dans un Fauteuil, les Bras Levés (Nude Seated in Armchair, Arms Raised) from 1963 shows a woman as a three-dimensional human (rather than disarranged limbs and apertures). She even seems to be enjoying herself, revelling in the outdoors, a sensual abandon in her posture, her expression. The painting ends just at the top of her pelvis – a little black V representing her pudenda. You feel he is appreciating and capturing something essential in the woman (again, presumably Jacqueline) rather than projecting his own attitude – anger, despair, fatigue – or desires, as with the other images in this room.

Pablo Picasso, Femme à l´oiseau (Woman with Bird), Mougins, 7 April 1971 (I). Fundación Almine y Bernard Ruiz-Picasso, Madrid. © FABA Photo : Marc Domage. © Succession Pablo Picasso / BONO, Oslo 2025.

In a filmed interview shared further into the show, from 1966, Picasso says: “My works have a personal meaning. In the end they are like memories that one writes to oneself in a notebook.” If that’s the case, these nudes, I can’t help thinking, would mostly be of the kind of notebook or journal that Picasso might have preferred to remain hidden from view. But they certainly have power.

The room titled Heads: Deconstructed, Reconstructed, is probably my preferred selection. These images are so playful, they feel vital. My favourite, Têtes (Heads, c1969-72), is rendered in felt pen and its dense arrangement of pattern, colour, texture and line has the vigour and expressiveness of some of Picasso’s later etchings and prints, which are, perhaps surprisingly, not included in the show

This restless quest to keep on painting, to repeat motifs, to cast paintings aside when still at that “doodle” stage recalls for me the 2022 Cézanne exhibition at Tate Modern, when it slowly became apparent why the artist returned to the same subjects, the same scenes, still-lifes and landscapes. But with Cezanne, as you looked at them, side by side, you could see and feel his desire to get closer to the essence of the thing. Is Picasso doing that? Not necessarily, or universally. Or is he so pleased with the vigour and verve of his doodles that he doesn’t feel the need to resolve or develop them into anything more profound?

He apparently told Brassaï: “I paint so many canvases only because I’m seeking spontaneity, and once I’ve expressed something with some success, I don’t have the heart to add anything to it.” But Berger’s point – identifying the malaise lurking behind Picasso’s success, the wealth, the fact that even a doodle might sell for substantial sums – I think is pertinent.

Picasso was clearly a man in possession of great genius, the masterpieces he has left us justifying his standing as arguably “the greatest” painter of the 20th century. And it would be entirely forgivable for an artist in their 80s to rest on his laurels. The aforementioned etchings, though, are explosive with ideas and energy, however questionable or violent the subject matter. You can see there is still plenty of creative vigour in Picasso, his life force seemingly flowing effortlessly from his mind to his hand to the page, or the etching plate. They are more complete, more resolved than most of the works shown here. But his name alone will surely be enough to get visitors to come to Trondheim. And once there, on the basis of its many attractions, including this gorgeous new art space, I hope they won’t be too disappointed.

• Pablo Picasso: The Code of Painting travels to the Moderna Museet in Stockholm (22 November 2025 to 5 April 2026) and the Kunsten Museum of Modern Art in Aalborg (7 May to 6 September 2026).