Edvard Munch, Sanatorium, 1902-03. Installation view, Lifeblood – Edvard Munch, Munch Museum, Oslo, 2025. Photo: Ove Kvavik. © Munch Museum.

Munch Museum, Oslo

27 June – 21 September 2025

by TOM DENMAN

We see a naked man lying on his back on a hospital bed. He stretches almost across the whole picture, at a very slight and yet wildly foreshortened diagonal – tiny feet trailing into the distance – evoking a dreamlike out-of-body experience. The diminishment – if not outright absence – of the man’s genitals signals an unresolved or liminal state of passivity. On the side of the bed closest to us, a nurse holds a bowl of blood; on the other side are three figures dressed in white, and behind them, through a window, an audience looks on. Within the folds of the bedsheet, close to the picture plane, is a bloody spillage almost dripping beyond the frame. The naked man is Edvard Munch, who depicted himself in On the Operating Table (1902-03) after he was shot in the hand – it was likely he who pulled the trigger – in an argument with his lover Tulla Larsen. The red puddle resembles a foetus. It could be Munch’s signature, or his “lifeblood”, as he referred to his art.

Edvard Munch, On the Operating Table, 1902–03. Oil on canvas, 109 × 149.5 cm. Photo: Juri Kobayashi. © Munch Museum.

With human blood acting as a metaphor for creativity and a substance gushing from the artist’s body, the painting – one of the first we encounter – epitomises the convergence of art and medicine that this exhibition explores. Thoughtfully curated by Allison Morehead, Lifeblood looks at the Norwegian painter’s close and committed involvement with a modernising medical world, marked by the emergence of anaesthesia and antisepsis, the invention of the X-ray, and the birth of the hospital as the main site of clinical treatment. We find a Munch who was not only the sickly and tortured artist we are familiar with, but someone actively conversant in early 20th-century advances in healthcare. The curatorial inclusion of medical artefacts alongside Munch’s paintings of doctors, nurses and the sick is commensurate with the artist’s own interests, reflecting his belief in art’s potential to heal. Among these objects are an X-ray of Munch’s wounded hand (1902), a sputum bottle used by those with tuberculosis (1890-1920), and an oxygen tank that the painter – ever-preoccupied by his own health – purchased in 1921.

Munch spent much of his life around doctors. His father was one, and his brother trained to be one before dying of pneumonia shortly after qualifying. A section of the show is dedicated to his much-revisited motif of a child in profile, her head on a pillow, pallid, frightened, feverish. The surface of the painted version of The Sick Child (1885-86) here is scoured and scratched, as if Munch were unable to leave it alone – indeed, beside the painting are two etchings (1894 and 1896) and six differently tinted lithographs (all 1896) of the scene, homing in on the girl’s face. Although he based the composition on someone he met while accompanying his father on a house call, he had in mind his sister Sophie, who had died at 15 of tuberculosis. His mother died of the same disease when he was young. Along with his own frequent bouts of sickness as a child, these deaths sowed in the painter a lifelong fear of contracting a debilitating if not deadly physical or psychiatric illness himself.

One of his earliest explorations of the strangeness of mortality, Death in the Sickroom (1893) theatrically contrasts the ways we react to the passing of someone we know. A woman in the foreground sits in a chair, her hands clasped on her knee, face red with tears. Beside her another woman stands, looking out, her skin ominously pale – or maybe this is the shock, and why she turns away, taking on the duty of reporting the news to us, the newly arrived visitors. In the background people sit, sob, pray, console. Some look, some look away. The deathbed is at the back of the room and we cannot see the corpse: Munch is concerned with the experience of death among the living. And yet the throbbing, lurid, “hospital” green of the walls, and the ambiguous pallor of the woman whose eyes meet ours, raise the morbid question of who is next. This pervasion of mortality also reminds us that that death is less a separate entity, cordoned off from life, than something that waits in all of us.

Edvard Munch, Women in Hospital, 1897. Oil and crayon on canvas, 110 × 100 cm. Photo: Halvor Bjørngård. © Munch Museum.

Munch’s sister Laura spent her life in and out of psychiatric hospitals, and the artist took a serious interest in mental health, using his contacts in the psychiatric world to gain access to asylums. Part of the exhibition highlights the gendering of mental illness – with women cast as “hysterics” and men, like the melancholic Munch himself, as “geniuses”. The two woodcuts Evening. Melancholy I (1896) and Melancholy II (1898) illustrate this discrepancy well. Depicting a man and a woman respectively, each sitting beside a shoreline, the man is given a thoughtful visage whereas the woman is depicted as deranged, her hair covering her face. It appears that Munch was trying to make a point. One large painting, Melancholy (1900-01), presents a woman sitting (in an asylum, we are told), her posture visibly tense, fingers curled, as she stares into the middle distance. The glorious light from outside ironically becomes a cage, as it projects the window frame on to the adjacent wall, wedging her between two grids. We can sense her fear, her lostness: feelings we can relate to because Munch renders them as real, rather than othering them as hysterical.

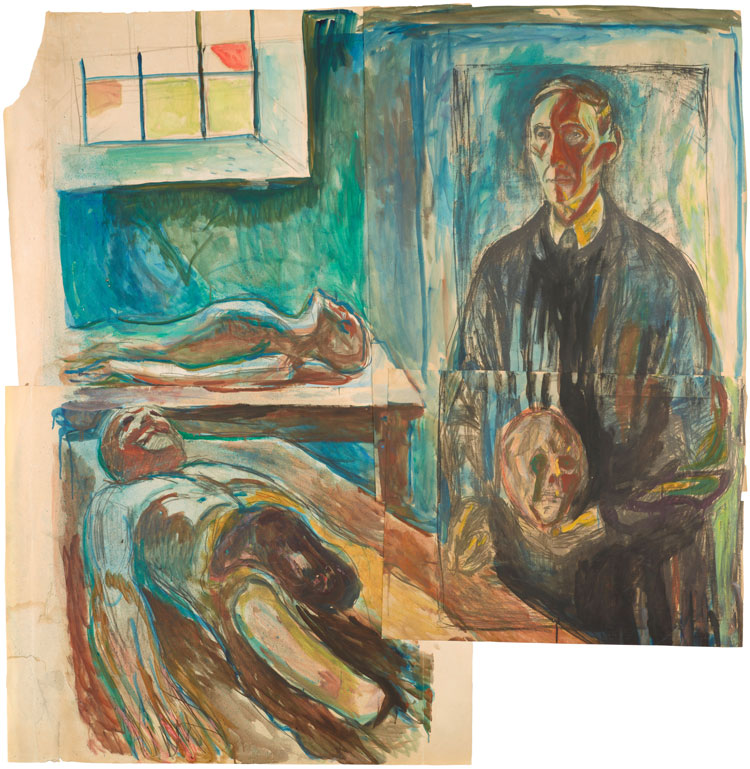

Edvard Munch, Anatomy Professor Kristian Schreiner, 1928–32. Collage: lithograph, watercolour, charcoal. Photo: Ove Kvavik. © Munch Museum.

A number of portraits illustrate the health-fanatical Munch’s close ties to the medical establishment, which he maintained throughout his life, even bartering art for the latest in healthcare. A portrait of his personal doctor, Kristian Schreiner (1928-32), shows him amid cadavers in a laboratory. The work’s fabrication out of multiple collaged sheets seems to allude to the anatomist’s practice of dismembering. A painting of the physician Lucien Dedichen informing the writer Jappe Nilssen of the latter’s terminal illness (1925-26) is a study of professional authority and care. Dedichen stands, unswerving in his diagnosis, while his backward lean gives the patient – slumped in a chair, mouth agape – the space to come to terms with the news, with the irresolution of Munch’s animated, unpolished brushstrokes and changeable greens, blues and browns immersing us in the mysteriousness of what lies ahead. Even if the diagnosis is final, the uncertainty-ridden experience of it is what Munch is driving at – what it might feel like for Nilssen, for the doctor, and for the artist who was friends with the two of them.

A section is dedicated to Munch’s stint at a private nerve clinic in Copenhagen in 1908, which followed an alcohol-induced breakdown. One of the show’s main strengths is the way it presents a Munch so invested in his health – he could fairly be described as a hypochondriac – that he was also, in certain respects, rather well and lived to the venerable age of 80. His painting Naked Men Swimming in a Pool (1923) – crammed with fit, strong bodies – and his photographs of himself standing proudly naked in the open air, evince an equal obsession with illness’s counterpart. In his old age, the vegetarian Munch took to painting still lifes of vegetables, their bright colours exuding vitality. One might wonder why a show dedicated to this eternal patient’s proactive engagement with the medical world has not been put on until now. But, of course, frailty (especially in men) goes hand-in-hand with genius, which is more of crowd-puller. Nuancing this image of Munch is a commendable feat, especially when the neoliberal cult of the individual threatens mutual accountability – and, with it, municipal healthcare among many other fragile things.

Edvard Munch, Kristiania Bohemians, c1907. Oil on canvas, 109.5 × 159.5 cm. Photo: Ove Kvavik. © Munch Museum.