Charles Ray. Untitled, 1973, printed 1989. Gelatin silver print, 68.6 x 101.6 cm. Purchase, Robert Shapazian Gift, Samuel J. Wagstaff Jr. Bequest, The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation Gift through Joyce and Robert Menschel, and Harriette and Noel Levine Gift.

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

31 January 2022 – 5 June 2022

by MARIE POHL

I am at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and I am lost. I ask one of the museum assistants for directions to the “sculpture of a naked man”.

“Oh, we’ve got hundreds of sculptures of naked men in here,” she answers. “What period is he from?”

“I can’t remember. He’s tall and naked. And clenching his fists.”

“Hm,” she wonders.

“And … moving forward!”

“Moving forward?”

“That’s what Charles Ray loves about him, his forward motion.”

Charles Ray, one of the most significant American sculptors, has an exhibition on the second floor, Figure Ground. After viewing it, I want to see the sculpture he discusses in all his lectures, essays and interviews. “I revisit it endlessly, in person and in my mind,” Ray said in the Artist Talk at the Art Institute of Chicago.

“Charles Ray is a disturbing presence in contemporary art,” wrote Calvin Tomkins in a 2015 feature about the artist for the New Yorker. “Famous but little known … so far from the mainstream that we sometimes forget he’s here.” Currently, “Mr Famous but little known” is stirring up the art world with four shows at the same time. Apart from the one at the Met, he has two in Paris, at the Centre Pompidou and at Bourse de Commerce – Pinault Collection, which have teamed up for a special two-part exhibition, running until 20 and 6 June 2022 respectively. And the Glenstone Museum in Maryland is curating a rotating exhibition of his works.

The media is buzzing with reviews. The reactions are controversial. In the New Yorker, Peter Schjeldahl crowned Ray an “artistic and philosophical provocateur”, and in the New York Times, which reviewed him twice, Roberta Smith called him a “radical conservative”, and Jason Farago praised him for “pushing sculpture to its limit”. Sebastian Smee, in the Washington Post, on the other hand, described Ray’s art as “lifeless as ash”. One friend told me she had never been to an exhibition so loaded with heavy references that did so little for her. It left her cold, she said, and refused to discuss it. Another friend fell in love with his latest sculpture, Archangel. Someone else noted: “I like his thinking.”

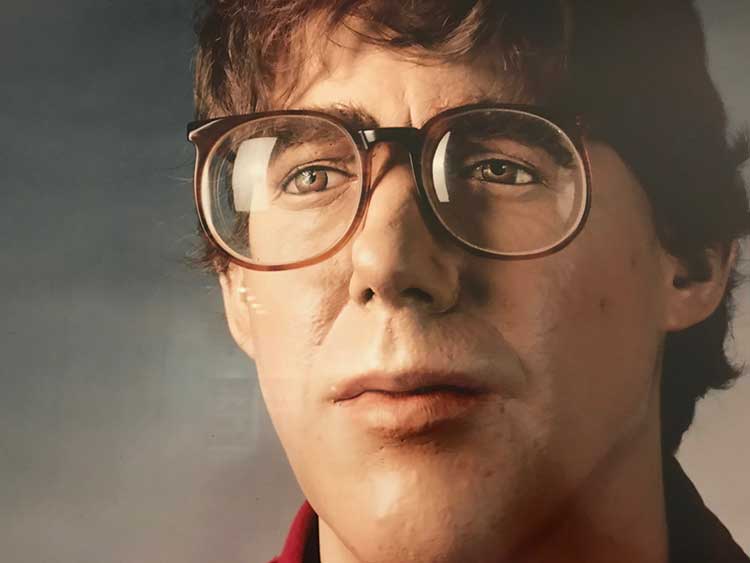

Charles Ray. No, 1992. Chromogenic print in artist's frame, 99.1 x 78.7 x 5.1 cm. The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, Gift of Lannan Foundation. Photo: Marie Pohl.

Figure Ground welcomes the visitor with a self-portrait Ray calls an employee-of-the-month photograph. The real title is No. The fibreglass mannequin is wearing one of Ray’s shirts and glasses. He took the sculpture to a photo studio for weddings and headshots. “I look like an employee of the month,” Ray explained in a conversation with Hal Foster, in the catalogue that accompanies the show. “No is exactly what it feels like to be me. The stiffness is a proper expression, not a mediated one.”

Stiff, self-aware and witty. Distant eyes, a slightly droopy mouth and the gesture of crossed arms all indicate a man who celebrates feeling awkward.

Ray was born in Chicago in 1953, but the family moved to Winnetka, Illinois, in 1960. He spent his high-school years at Marmion Military Academy, a Catholic school in Illinois, which he hated. He was generally uncomfortable around people, Ray told Tomkins: “I wasn’t the class nerd, but I was weird.” And though Ray has been living under the Californian sun, teaching at the University of California, Los Angeles, since 1981, his Midwestern-childhood-awkwardness has remained with him. After all, where could it have gone?

Charles Ray. No, 1992 (detail). Chromogenic print in artist's frame, 99.1 x 78.7 x 5.1 cm. The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, Gift of Lannan Foundation. Photo: Marie Pohl.

The contrast pulls you in, an almost feminine fragility in his facial expression contradicted by experienced, manly hands that ground the sculpture like a pedestal.

Charles Ray. No, 1992 (detail). Chromogenic print in artist's frame, 99.1 x 78.7 x 5.1 cm. The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, Gift of Lannan Foundation. Photo: Marie Pohl.

The Met curators Kelly Baum and Brinda Kumar, together with Ray, selected 19 artworks from every period of his 50-year career. It is a sort of mini-retrospective of an artist who sculpts with a wide array of materials, ranging from his own body, to fibreglass, ink, porcelain, aluminium, steel, handmade paper and wood.

“I deny subject matter,” he repeats often, almost like a mantra. Every decade, he switches lanes, taking on new materials and sculptural forms. The show dives into this multitude. So do both shows in Paris. How can they not? Like an actor, Ray takes on different roles, abstract, conceptual, figurative, and this versatility has become his trademark.

A pioneer, he continuously innovates the technical and formal possibilities of sculpture. He combines human and robotic hands, adding the computer-triggered chisel to the cabinet of sculpture tools. Such machined works, made from solid blocks of stainless steel, are Huck and Jim (2014) and Sarah Williams (2021). Both were inspired by a scene in Mark Twain’s 1884 classic The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.

“I was keen from the beginning to make Huck and Jim and Sarah Williams the conceptual and physical anchors for this exhibition,” Baum told me in an email. “It felt important to give the public the opportunity to grapple with these challenging sculptures.”

Charles Ray. Huck and Jim, 2014, Stainless steel, 283.2 x 137.2 x 136.5 cm. Collection of Lisa and Steven Tananbaum. Photo: Marie Pohl.

Ray started to work on Huck and Jim in 2009. The Whitney Museum of American Art had commissioned a fountain for the plaza outside its new location in the Meatpacking District from an artist it had featured with a retrospective in 1998 and invited to five Whitney biennales. Ray turned to Twain’s Homeric epic to express the American identity of the museum. Set before the civil war, Huckleberry Finn tells the story of two runaways, Huck, a white boy fleeing an abusive father, and Jim, a black man running from slavery.

The Whitney rejected the sculpture, concerned about its nudity. A nine-feet tall naked African American man standing next to a naked, bent over white child could offend people. It didn’t matter that Huck says in the novel: “We was always naked, day and night, whenever the mosquitoes let us … besides I didn’t go much on clothes nohow.” The sculpture (like the book many a times) was deemed inappropriate for a civic space.

It is important to recall Ray’s original idea when looking at Huck and Jim, and to remember it was meant to be a fountain – outside. The sculpture refers to chapter 19 in the book. Huck and Jim discuss the origin of stars. Huck believes they “happened”. It would have taken “too long to make so many”. Jim thinks the moon laid them. Having seen a frog lay thousands of eggs, that seems reasonable to Huck. Ray envisioned the fountain water flowing out of Huck’s hand into a pond with sculpted frog eggs.

“He’s got a computer-face,” I overheard a visitor say to the woman he was with, pointing at the sculpture of Jim. “I don’t like the steel,” she agreed, “gives me the shivers.”

I longed to see the clay model Ray made in an earlier stage, and wished Huck and Jim looked like the earth they slept on out in the wild. Then I imagined the sculpture in front of the Whitney. It would have withstood the weather and blended into our steel world. Inside, the sculpture seemed displaced, triggering the controversy the curators had intended.

Charles Ray. Sarah Williams, 2021. Stainless steel, 239.1 x 78.7 x 173.4 cm, Collection of the artist, courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery.

A few years later Ray doubled down with Sarah Williams (2021), sculpting a scene from chapter 10 of the book. Jim has not yet grown the bushy hair that we admire in Huck and Jim. He’s bald. He has just recently escaped his master. He is fully dressed. So is Huck.

Ray seems to ridicule the critics. They want them clothed? I’ll put clothes on them. Huck wears a girl’s dress. Jim kneels behind him fixing the hem. The two are trying to disguise Huck’s identity before he sneaks into town to inquire about the hunt for them. It is a suspenseful moment in the book that leads to their journey down the Mississippi river.

As I studied the sculpture, the coldness we identify with steel began to soften. The reflecting light and the delicately crafted details made it come alive. The wrinkles on Jim’s pants, his loose shirt, the space Ray created between the fabric and Jim’s chest. In contrast, the dress clung tightly to Huck’s chest, like the armour of a knight. And their facial expressions, the calm anticipation of the danger they were about to confront. There was so much story in these details that the hardness of the material became irrelevant.

Charles Ray. Boy with frog, 2009. Painted stainless steel, 243.8 x 74.9 x 104.7 cm. Philadelphia Museum of Art, Promised gift of Keith L. and Katherine Sachs.

Figure Ground unites for the first time Ray’s three Huckleberry Finn sculptures, Huck and Jim, Sarah Williams and Boy with Frog. I call the latter the boy with one nipple. Boy with Frog is not a direct depiction of Huck Finn. The sculpture is inspired by the book. It is eight-feet tall, stainless steel, cast and painted white. Ray gave his boy a belly bloated like a balloon, like children have, filled with wonder and excitement. He caught a frog. The amphibian stretches its left leg out to the side. Will the boy let the frog go? The ferocity in the frog’s plain white eyes is intense.

The boy’s testicles are odd. They look old and wrinkly. Like the skin of the frog, they are extremely detailed. A reference to birth? Sperm – frog – frog eggs – origin of life? Ray tends to direct the viewer’s focus by making certain body parts more prominent than others. Like the boy’s chest, which has only one nipple. The curators explained that Ray had removed one, because it “interfered with the spatial and perceptual relationship between the boy and frog”.

Ray’s manipulation of perception is a common thread in his work. Take his 1989 sculpture 81 x 83 x 85 = 86 x 83 x 85 located across from Boy with Frog.

Charles Ray. 81 x 83 x 85 = 86 x 83 x 85, 1989, Aluminium, exterior: 81 × 83 × 85 cm; interior: 86 × 83 × 85 cm, Pinault Collection.

Richard B Woodward, in the Wall Street Journal, calls it “ostensibly a parody” of Donald Judd’s metal box. When Ray discussed Judd in his lecture Thoughts on Sculpture III, he asked: “Is he really about boxes or is he really about a geometry of viewing?”

You can walk up to the box and look inside. It’s empty. The magic happens when you step away from it. Then you notice that Ray has sunk it into the ground. Hence the title 81 x 83 x 85 = 86 x 83 x 85.The left side of the equation gives the exterior measurements, the right side gives the interior ones. The 5in difference results from the box sitting not on but in the ground. In his catalogue essay, Ray writes, he likes to run equations on either side of the equal sign. “I sculpt the equation between you, the viewer, and the work.”

The exhibition itself seems to follow a mathematical equation: 19 pieces, arranged in two galleries, nine works in each room, with his self-portrait at the entrance as the balancing equal sign. Given his attention to numbers, it may not be coincidental that the total number of works, 19, aligns with chapter 19 in Huckleberry Finn, in which Huck and Jim discuss the origin of stars (and frog eggs).

Also located in the first gallery are three little sculptures that elaborate on this loose narrative. Having passed Ray’s welcoming self-portrait, one turns the corner and finds Chicken (2007), Handheld Bird (2006) and Hand Holding Egg (2007). The three small pieces resembling birth are painted white and kept in a glass case like premature babies in an incubator. You almost don’t want to disturb them. They seem so fragile.

Charles Ray. Chicken, 2007. Painted stainless steel and porcelain, 4.4 x 5.7 x 4.4 cm, Glenstone Museum, Potomac, Md.

Swaying back and forth from narrative interpretations (beginning – eggs – birth – stars) to abstract sculptural ideas is part of the process of approaching Ray’s art. Chicken shows us an egg made from stainless steel. Through a hole, we can make out the tiny claw of the hatchling inside, made from porcelain. Originally, the hole was a naturally shaped break in the egg, but Ray felt the sculpture looked static, so he replaced it with an abstract, perfectly round hole. “It’s a sculptural element, in a dynamic relationship to the viewer and the chicken,” Ray explained to Foster.

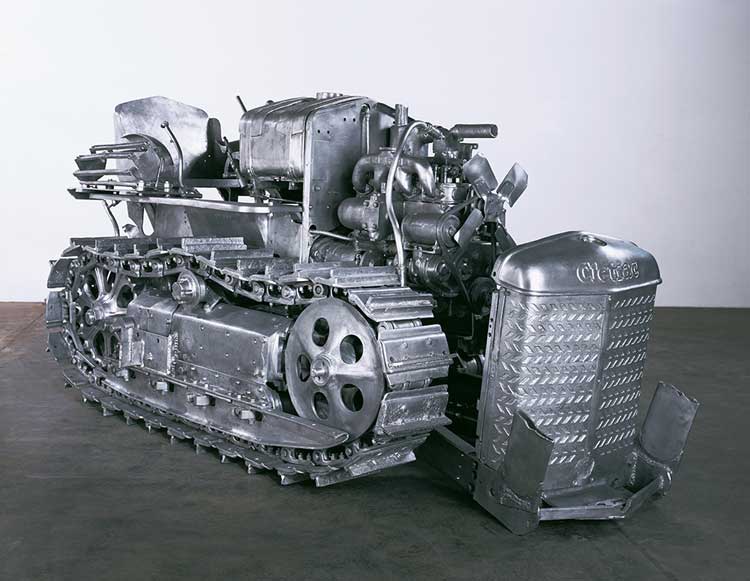

Charles Ray. Tractor, 2005. Aluminium, 143.8 x 306.1 x 154.9 cm. Glenstone Museum, Potomac, Md.

At plain sight, Tractor (2005) evokes an American feeling: farmland, farm work, a broken-down tractor like a broken American Dream. The sculpture stops short before the sunken box, 81 x 83 x 85 = 86 x 83 x 85. But Tractor is a lot bigger, sized like the real tractor on which it is modelled. I eavesdropped as the elderly couple who disliked Huck and Jim were discussing Tractor. The man led the analysis.

“It’s an artfully disassembled tractor … that …”

The woman interrupted, “was reassembled …”

“... that emphasises,” he put some weight in his voice, “the raw, mechanical nature of the device.”

The woman corrected him: “Machine. You said device. It’s a machine.”

“Right, machine.” He pointed to the nose-cone grill. “That’s the radiator. Or whatever that is.”

“That’s the front part. Isn’t that the front part?”

“Exactly.”

“Why is it coming off?” She seemed genuinely worried.

“Because the thing is dead.”

The story goes that Ray was trying to sculpt a tractor he played on as a child, when a friend told him about an abandoned tractor in the San Fernando Valley. It had blown a rod and been decaying for 50 years. Ray brought it to his studio, took it apart, and then started to remake it, casting every single part in aluminium. He calls it “a philosophical object”.

“Every part is handmade,” Ray told Foster. “At one point, there was a portal that you could open. I finally told the fabricator: ‘Now it’s time to weld this portal shut.’ He goes: ‘What do you mean? No one will ever be able to see into it.’ And I said: ‘If we leave it open, that’s all people will do. The sculpture will be over.’ I see it as a tractor in heaven.”

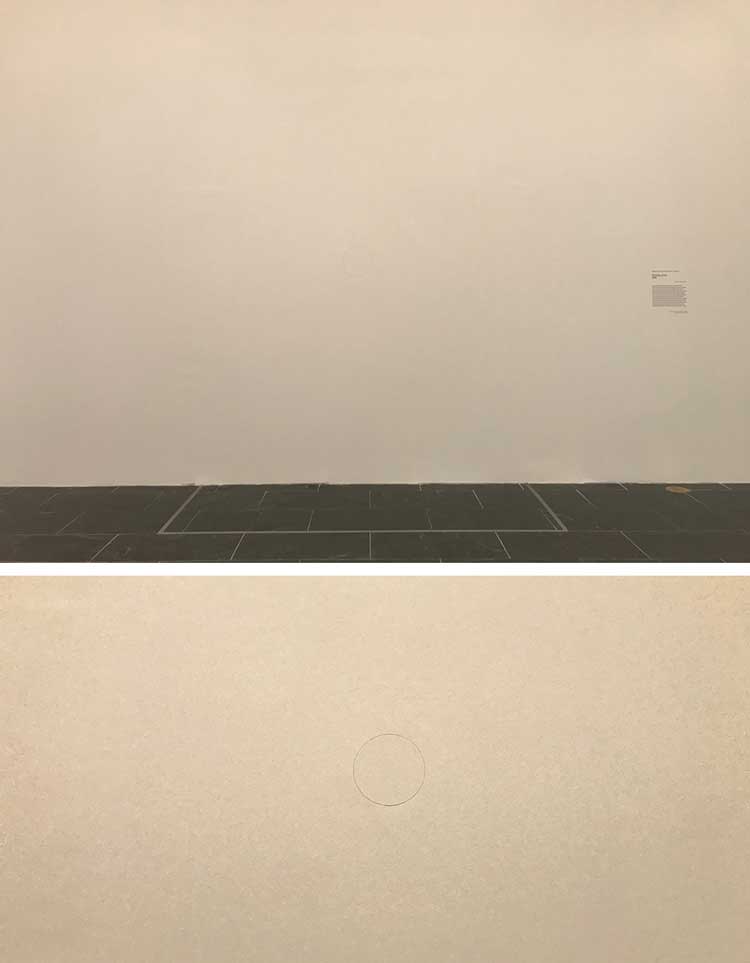

Charles Ray: Figure Ground, installation view, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 2022. Photo: Marie Pohl.

“Space is the sculptor’s primary medium,” is possibly Ray’s most quoted statement. Space is present in the entire installation. Entering the galleries from the densely packed hallways of the Met, I felt my chest expand. Ray’s sculptures have space to breathe. And the visitor has space to think. The art conservator Christian Scheidemann, who has worked with Ray, told me that every time Ray sends a sculpture to an art collector, he has the urge to send along eight boxes filled with space.

Charles Ray. Plank piece I and II, 1973. Two gelatin silver prints, 100.3 x 68.6 cm each. Private collection. Photo: Marie Pohl.

The person in Photo of Plank Piece I and II is Ray himself. He performed Plank I and II in 1973, while at the University of Iowa. The work boots he wears are powerful, adding weight to his seemingly weightless body. They reminded me of his strong hands in the self-portrait No.

Until the mid-80s, Ray frequently used his own body as sculptural material, almost as if he were performing sculpture. For A Geological Take on Time, he put himself inside a gigantic clock, mounted on a wall, his legs dangling out like living pendulums.

When he was young, he couldn’t draw, but he always enjoyed building things, he told Ben Luke, host of the podcast A Brush With. He faked his way into the University of Iowa, he said, and into an advanced sculpture class with the modernist sculptor Roland Brener, who taught him that art was less about making something than about discovery.

“The idea of drawing was forbidden. We drew with real materials, with things, moving them around on the floor, locking them together,” Ray explained. He still had trouble with his hands: welding, making clean cuts, painting objects a solid colour. He calls it a sort of hand-dyslexia. “I just propped things together and that brought on a kind of anxiety that is still in my work.”

Ray turned his weakness into strength. He learned to ask others to weld and cut for him. To this day, his studio employs a large number of artists who make the moulds and casts. He hires highly skilled fabricators for the wood, steel and aluminium work. It is funny how clean and impeccable his pieces are, considering his hand naturally implores a messy imperfection. Eventually, Ray did begin to draw. In 2003, he started painting beautifully imperfect flowers. But they are not exhibited here.

Ray’s strict sense of exactitude, especially in his conceptual works, perhaps has its origin in the education he received at the catholic military academy as a child. In one of his lectures, he even says: “I am 90% military school – still.”

As I contemplated Ray’s confined high school years and his striking posture in Plank Piece I and II,the elderly couple returned from the second gallery room. The woman was scared of the mannequin sculptures she had seen there.

In 1990, Ray surprised everyone with fibreglass mannequin sculptures. It was yet another drastic shift in his career. He had gone from creating sculptures in outdoor spaces to incorporating his own body, to conceptual works using domestic objects, to perceptual illusions like his elegant Ink Line and just as he was making a name for himself, he turned to figuration.

“If I look at another one of those mannequins,” the woman moaned, “I am going to have nightmares.” The man was appalled by their “boyish little asses”. He went back to Tractor and stood there for a moment, almost in mourning, his head down. “I do like the tractor.”

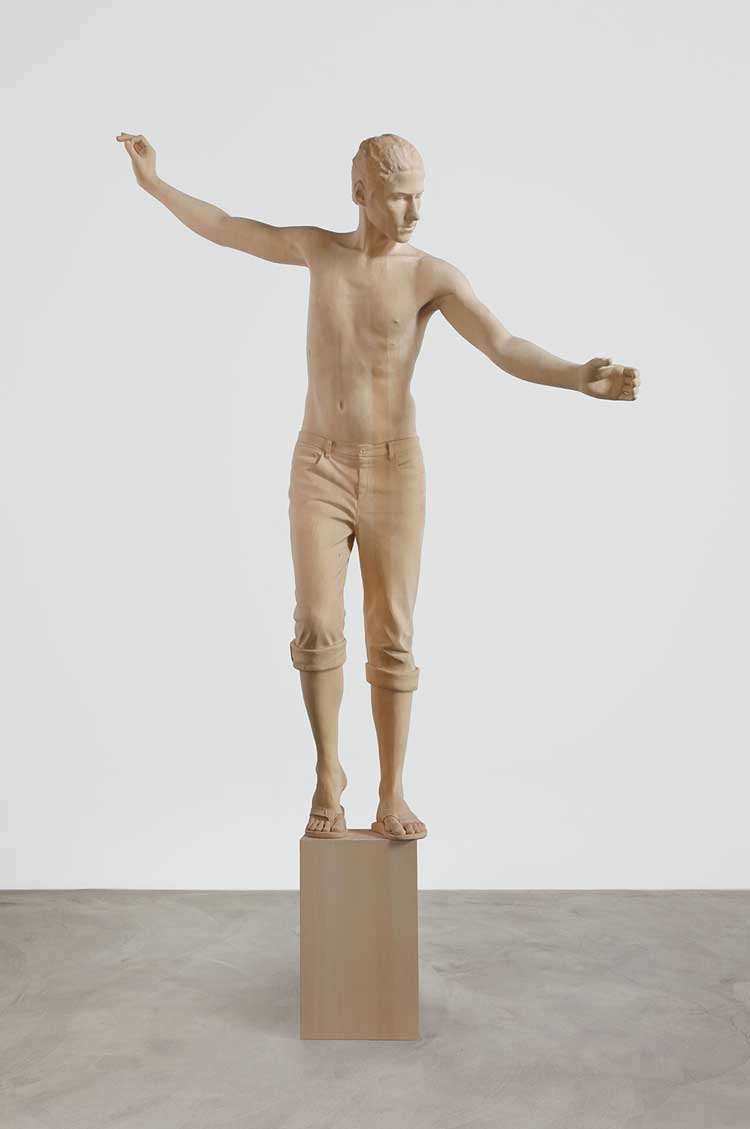

I was a little frightened about entering the gallery alone. Luckily, the sculpture that greeted me was not an eerie mannequin but Archangel, a new work, finished in 2021, carved from one solid piece of Japanese cypress wood, 13.5 feet tall, like a gigantic bird descending from the sky.

Charles Ray. Archangel, 2021. Cypress, 410.2 x 227.3 x 115.6 cm, Collection of the artist, courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery.

A stranger approached me and asked my political opinion of Archangel. There was nothing political about him. He was flying in with the western sun on his body, on his hair – glowing in honey-coloured wood. Maybe he was a surfer from California? He wore rolled-up trousers and flip-flops, and his hair was tied in a bun. Riding the waves. Beautifully sculpted. The man pointed to the wall text. Ray had been in Paris during the terrorist attack on the offices of Charlie Hebdo.

“Ray envisioned the archangel Gabriel, a guardian figure in Judaism, Christianity and Islam, alighting on to unstable ground,” the wall text concluded. I wished Ray had hidden the missionary aspect of the sculpture like the motor parts in the tractor.

Charles Ray. Rotating circle, 1988. Electric motor and disc, dia. 22.9 cm. The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, Gift of Lannan Foundation. Photo: Marie Pohl.

Next up: Rotating Circle. Where was the sculpture? There was a wall text and an indication on the floor, but no sculpture. I stepped closer and heard a motor humming behind the wall. Then I noticed the circular incision. It stood still. Zero movement. Ray had embedded a metal disk with a hidden motor in the wall. It spun so fast that it appeared stationary. He tried to “pour all his angst” into this sculpture, he tells us in the catalogue. “I mounted it at head height like a portal or, possibly like a self-portrait. A placid disk, a simple circle for the head …”

I stared at Rotating Circle looking for Ray’s angst in the sculpture. Ray loves circles. He loves squares, too. For any sculptor, geometry is part of daily life, but circles hold a special place in his heart (and head). He dedicated his entire first lecture at the Menil Collection to holes and circles. “The mathematical definition of a hole is an object that can’t be shrunk to a point. That’s a profound thought,” Ray said, and elaborated. Every sculpture needs an armature, every idea needs an armature, like a clothing line to hang your clothes on. “It can be seen like a wire in the brain that you start building around. Putting things on. Holding things.”

Ray deduces that if a circle cannot be shrunk to a point, it cannot have an armature. It is a sculptural object without armature, without a ground, without anything to hold on to, eternally spinning. Understandably, that may push the sculptor, who went to military academy, into a severe state of angst. Ray concludes that, if a circle cannot have an armature, it becomes the armature.

It all boiled down to a circle. And for me, too, things were slowly starting to spin out of control. Hanging out with these sculptures for so long, I began to treat them like living beings. I felt bad for the sunken box on the other side of the wall. It was unprotected. It had to deal with people all day, looking inside it, and if the guard didn’t pay attention, touching it.

Suddenly, I felt the presence of someone behind me. Someone was staring at me. I turned around. It was the daughter of the Family Romance gang. Her face was deeply disturbing. Family Romance and Boy, across from it, are two of Ray’s earliest fibreglass mannequin sculptures. The family members are all the same height, 4.5 feet tall or short, depending on which one you are looking at.

Charles Ray. Family romance, 1993. Painted fibreglass and hair, 134.6 x 215.9 x 27.9 cm. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of the Peter Norton Family Foundation.

Family Romance, also exhibited in the Paris show, takes its name from Sigmund Freud’s family-romance-complex, an analysis of children discovering that their parents are not always wholly emotionally available. The title also refers to George HW Bush’s slogan “family values”.

None of the four mannequins is aware of the other. Each stares into the distance. Alone. Yet they hold hands. The absent-minded father. The exhausted mother. The son is the liveliest one. A faint curiosity is painted into his glass eyes. The daughter’s face troubled me.

Charles Ray. Boy, 1992. Painted fibreglass, steel, fabric and glass, 181.6 x 99.7 x 52.1 cm, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, Purchase, with funds from Jeffrey Deitch, Bernardo Nadal-Ginard, and Penny and Mike Winton. Photo: Marie Pohl.

Like Family Romance, the figure of Boy is also disproportioned. It has the face of a child and the height of an adult man (Ray specifically). Boy is patterned on a store mannequin, complete with its base. Its cheeks are puffy, like a kid who has had too much candy. The right hand mimics a gun.

The sculpture is positioned in the middle of the room and his finger gun is pointing at the wooden peace-maker Archangel. Ray has often discussed the importance of how his sculptures relate to one another when exhibited together, the same way various parts within one sculpture interact with each other, like the nipple and the frog in Boy with Frog. And, finally, how the viewer relates to the sculpture. It all leads back to his perception-game. What we perceive is influenced by the interplay of relationships.

Charles Ray. Mime, 2014. Aluminium, 64.8 x 196.2 x 73.7 cm. Hill Charitable Collection.

The sparkling, sleeping Mime is stretched out on a cot. The sculpture almost appeared to be liquid, like a calm, glistening lake. Ray can take a decade to finish a sculpture and wait another few years until he decides to show it. The long process of deliberating how to make Mime began with three-dimensional digital scans of a real mime, Lorin Eric Salm. Ray made a fibreglass model and sprayed it white to study the forms. For years he looked at it, like “looking down at a cloud”, Ray told Toby Kamps in the Brooklyn Rail.

Ray couldn’t find the reality of the sculpture. It was an image. He needed to break the image. Perhaps wood? He hoped, a carver’s hand, a chisel could break through the image. He travelled to Japan and entrusted Mime to the wood carver who had made his famous tree trunk sculpture, Hinoki (2007), which is exhibited in Paris.

Months passed. While waiting for the wooden Mime, he had another idea. Maybe the robotic arm that he used for his machined aluminium sculptures would do the trick and succeed to break “the cloud”. For Ray, the robotic hand is not completely detached from humanity – after all, a robot is only a robot because a human programs it.

“It takes a lot of files to teach a robot how to carve a form. Where to leave the work, where to come back,” Ray explained. Crossing over the surface, the robot leaves lines on the aluminium, like the lines we used to see on CDs shimmering in rainbow colours when we held them into the light, as did Mime’s skin.

Ray ended up making two sculptures of Mime. One in wood. And one in aluminium. The wooden one is currently on view in Paris. Ray does not show them together to avoid favouritism.

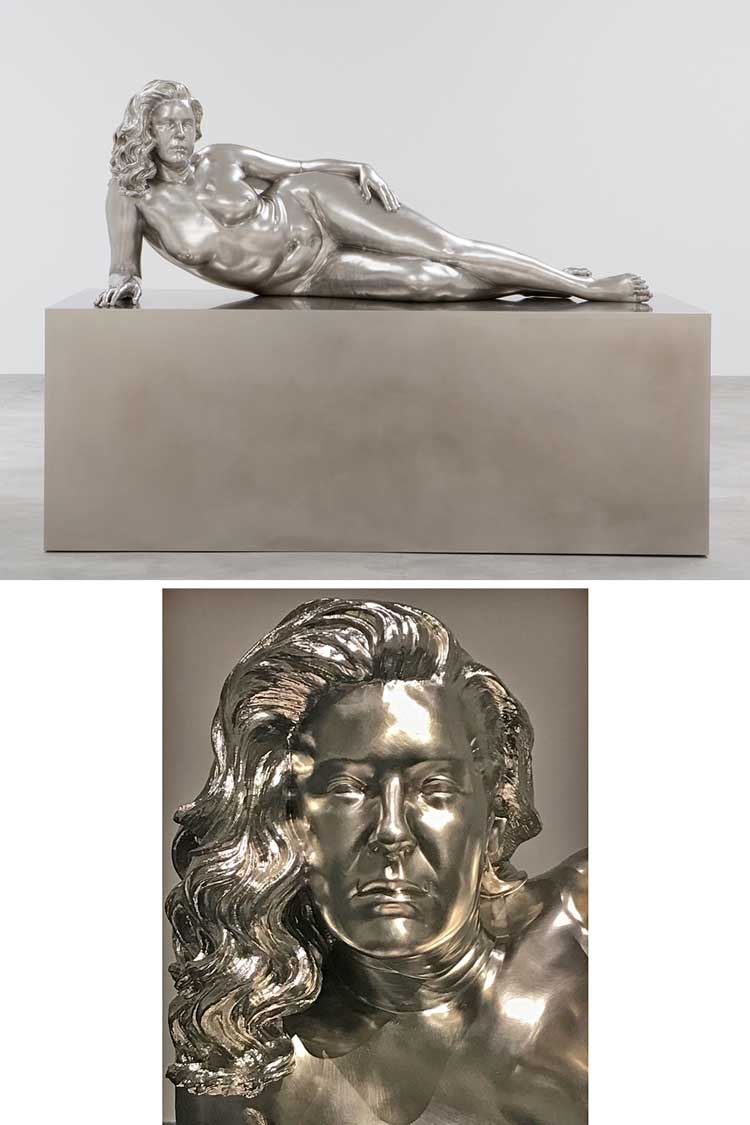

Charles Ray. Reclining woman, 2018. Stainless steel, 151.8 x 210.8 x 111.8 cm. Collection Glenn and Amanda Fuhrman NY, Courtesy the FLAG Art Foundation.

Next to Mime was another figure made through the machined sculpting process. Reclining Woman (2018) is a stainless-steel figure on a massive stainless-steel block. The model for this work was a banker. She was facing the back of Archangel, while the shooting Boy was diagonally positioned to them. She literally had Archangel’s back. Her posture was relaxed. Her size, weight and age seemed proportional. She even had cellulite.

The reclining nude figure burst with art-historical references, but I was drawn to her body, facial expression and beautiful hair. Many critics call this sculpture the “mean banker lady”. I couldn’t read her face. She was not angry. There was something else bothering her. The model for the sculpture was near-sighted. When she took off her glasses, she looked at you, but could not see whether or not you were looking at her.

Still, the sculpture gave off an aura of safety, like people who are centred and secure with themselves. The reason lay in its armature. Ray had built this sculpture around a line he imagined, running from its toes to the eyes. A nerve, he says. A tension inside her body that grounded her, and gave her strength.

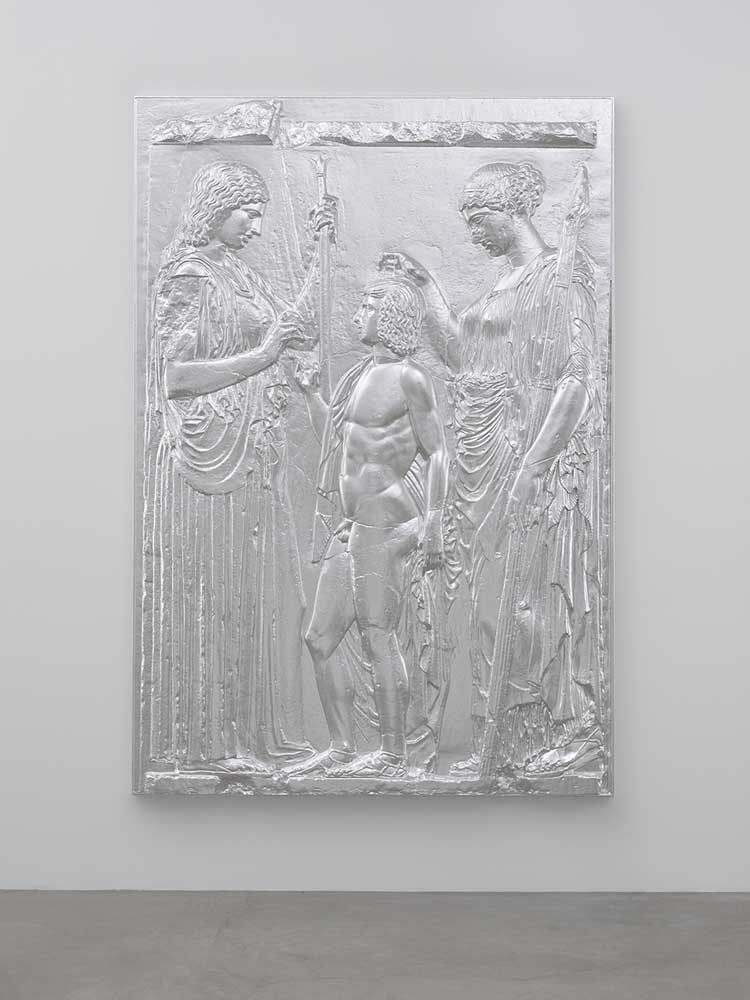

There was one more sculpture before the exit – A Copy of Ten Marble Fragments of the Great Eleusinian Relief (2017), an aluminium copy of the original fragmented relief at the Met.

Charles Ray. A copy of ten marble fragments of the Great Eleusinian Relief, 2017. Aluminium, 232.4 × 160.7 x 12.1 cm. Collection of Joshua and Filipa Fink, New York.

Placing this sculpture at the end of the exhibition made sense: it is a tribute to the Met and to the history of sculpture itself. Ray is known for referencing other works in his art, such as in Mime, where he takes on the Sleeping Hermaphroditus at the Louvre. He is not only inspired by his masters, he converses with them, continuously moving sculpture forward into the future without losing touch with the past.

The sun would set soon. I yearned to take a stroll in Central Park and ponder what I had seen. Ray takes long walks: he gets up at 2.30 every morning and walks for miles.

I said Goodbye to Huck and Jim dressed for the Sarah Williams scene. The sculpture faced the door and seemed uninvolved with the mannequin and circle madness in the room. I bowed my head as I stepped out, and smiled when I saw Twain’s book in a beautiful leather-bound edition next to the Ray catalogue. If all fails to move, puzzle or intrigue the visitor, the mere fact that Ray puts Twain’s masterwork on the table marks an achievement. Michelangelo gave us David, Ray gives us Huckleberry Finn, and thus continues the sculptural tradition of portraying epic tales. In his case, an American one.

Before leaving, I wanted to see this one sculpture Ray had talked about so often. This forward-moving, tall, naked man that was somewhere here at the Met. The impressions of Ray’s show were clouding my memory and I couldn’t for the life of me remember its name.

On the way to the staircase, I passed the sculptures of Auguste Rodin. In one of his lectures Charles Ray tells the story of how Rodin introduced his monumental Balzac to the public and critics scolded him for having draped the great novelist in a bathrobe. No human figure, they said, could be under such drapery. He’s deformed, they said. Rodin invited the critics to his studio, hammered open the bathrobe of the plaster model, and showed the critics Balzac’s perfectly protruding belly, his crossed arms resting on it. Ray loved how Rodin had sculpted something the viewer would not see, a perfect belly underneath a robe, like his motor parts inside the tractor.

I hurried downstairs, rushed through centuries of Egyptian history, got lost among tombs and hieroglyphs, looking at everything differently now with Ray’s geometric eye, noticing the diagonal lines of the slanted windows above the pool in the Temple of Dendur, the proportions of the pharaohs … but where was Ray’s favourite sculpture?

“Tall, naked, clenching his fists … and moving forward… Do you remember any other characteristics?” the friendly museum assistant asks me.

“His testicles. Ray discussed his testicles.”

“What did Ray say about the testicles?”

“There’s life in them. They’re pulsating with life.”

“Hm. I don’t know if I ever studied the testicles of our sculptures,” she admits shyly.

“They’re natural. Not stylised – like the hair. Wait. He’s got braids!”

“Oh. It could be Kouros.”

“Kouros! Kouros! That’s it! That’s him!”

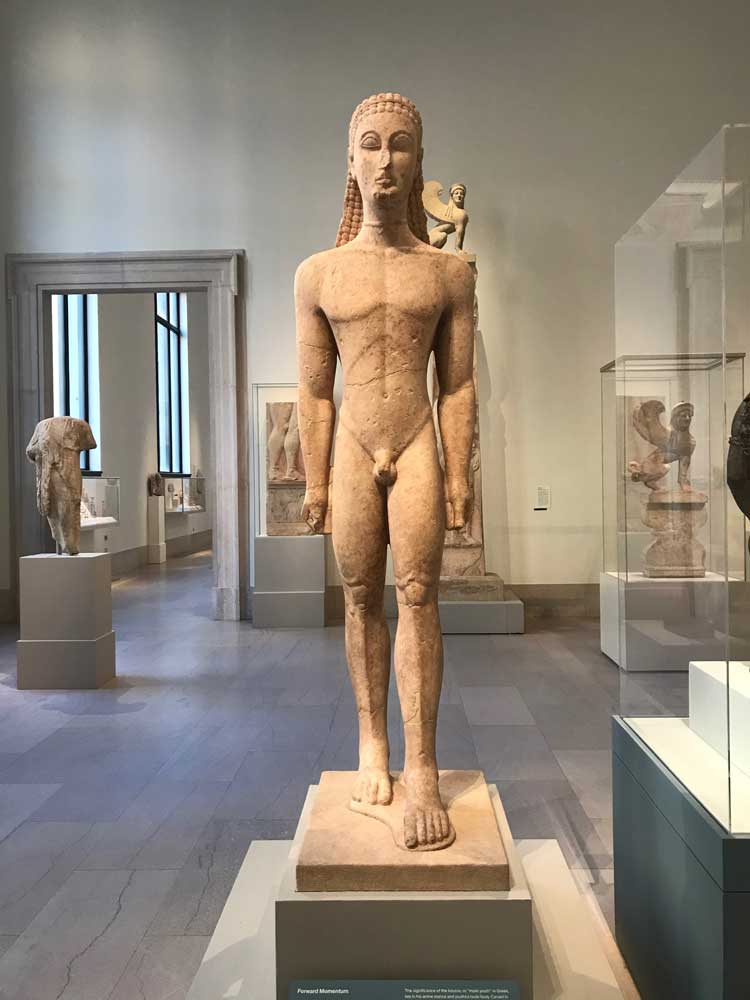

She directs me to the galleries of Greek and Roman art on the other side of the majestic entrance hall. Everyone knows the Kouros here. He’s famous.

Famous but little known … and not just at this museum, but all over the world. The Kouros doesn’t represent a particular individual, but a general idea of male pubescence. In Ancient Greek, kouros means “male youth”. And the most beautiful aspect of this archaic sculpture is indeed its eternal youth.

It reminds me a bit of Charles Ray in his lecture videos, determinedly striding forward with slightly droopy eyes.

Forward Momentum, marble statue of a Kouros, Greek, c590-580 BC. Stone sculpture, 194.6 × 51.6 × 63.2 cm. Fletscher Fund, 1932. Metropolitan Museum of Art New York.

I am relieved to learn my assumption that Kouros was Egyptian, isn’t totally off. He’s dated c590-580BC. His appearance coincides with the reopening of Greek trade with Egypt. Just as Ray references his predecessors, so did the Greek sculptors. The stone carving technique and the geometrics are influenced by Egyptian craftsmanship. Like the Egyptian figures, he is cubic, starkly frontal, broad-shouldered and narrow-waisted. The arms are held close to the sides, fists clenched, and both feet are firmly planted on the ground with the left foot slightly advanced. But unlike the Egyptian sculptures, the Greek kouroi had no explicit religious purpose. They served, for example, as tombstones for wealthy citizens and commemorative markers, or were found in sanctuaries. And the Greek kouroi were nude.

The New York Kouros is one of the earliest monumental kouroi. “It doesn’t begin the nude tradition in Greek art, it monumentalises it with larger-than-life stone sculptures on public display. This has to do with a moment in society of celebrating the male nude body. Men practiced athletics in the nude. There was public male nudity,” says Hallie Franks, an associate professor of ancient studies at New York University’s Gallatin School.

I am immediately reminded of Ray’s Huck and Jim, which was not allowed to reside in front of the Whitney Museum, because Ray sculpted Huck and Jim in the nude. Although the positioning of the legs and arms differ, there is a resemblance to Kouros in Ray’s sculpture of Jim, the forward gaze, the proud, upright shoulders, the musculature, and its eternal youth.

The resemblance to some of Ray’s other pieces is even more striking. The little wooden male figure in Ray’s sculpture Puzzle Bottle (1995), for example, though fully clothed, has the same forward-striding left leg and the arms to the side. Also, his nude Aluminium Girl (2003) and Young Man (2012) make clear references in their postures, although Ray always adds a slight touch of melancholic humour to his sculptures.

Ray admires the intentionality of the Kouros. The clenched fists, the forward stride, the forward momentum. Where is it walking to? It adds suspense to the sculpture. This intention is fundamental to Ray’s work. He depicts a moment in time and includes the question of what will happen next. Is Mimereally sleeping? When will it wake up? And what will happen to Sarah Williams when Huck goes into town dressed like a girl? Even the conceptual pieces express this vitality. Will the box keep sinking until it disappears? Will Rotating Circle ever stop spinning, or will we ever see it turn?

Ray endlessly projects into the Kouros figure. He sees in it a coexistence of stylisation and naturalisation, and to Ray: “That’s what we are.” The testicles are natural, while the hair looks as if “a nine-year-old girl doodled it in her notebook”.

“We’re a crazy mixture of good, bad, naturalism, stylisation. I stylise myself in a certain way to function … But there are parts of us that we can’t stylise. The way we walk,” Ray says in his lecture Thoughts on Sculpture I.

Ray plays with that same coexistence of stylised and natural elements in his art. He mixes the conceptualised with the innate, abstract thinking with inherent movements, philosophical and psychological contemplation with quiet gestures, the heavy with the weightless. The figure with the ground.

Figure Ground. The title of the exhibition comes to mind as I see the Kouros balance two tons of weight on his ankles and feet.

“A sense of gravity, of a strong relation between the form of the object and the ground on which it lies, has been central to most vital modern sculpture since Rodin,” writes William Tucker in his book The Language of Sculpture.

The term Figure Ground, the curators informed me, “has its origins in gestalt psychology”, a theory of perception that emerged in the early 20th century. One of its principles is the figure/ground relationship, a concept often illustrated with the “faces or vases” illusion. Depending on whether you see the black or the white as the figure, you may see either two faces in profile or a vase in the centre. The ground can be the figure, and the figure can be ground, depending on your focus. Perception varies, it can be altered. To Ray, it offers a multitude of sculptural possibilities.

“For a ‘figure’ to be both legible and intelligible, it needs a ‘ground’,” the Met curators explain. “The ‘ground’ is the condition of possibility for any ‘figure’ to appear. Deeply invested in exploring the fundamental terms and conditions of both perception and sculpture, Ray activates figure/ground relationships in a variety of ways.”

Rotating Circle. The metal disk grounded by a motor in the wall, spinning so fast, we cannot see it move. In one of his lectures, Ray brings up Copernicus. The Renaissance polymath introduced the notion that the sun and not the Earth is at the centre of our universe. Ray surmises that, 500 years later, society sees the world as a construct and “we are the centre again”. Today’s selfie-culture reflects this idea. The more people spin around themselves, the less they relate and interact, and the more they are stuck. Another variation is Archangel, who descends on to “unstable ground”, into a time with a lost sense of purpose, little common truth and a confusion about what is fact. But there is also the beautiful, voluptuous Reclining Woman grounded on her solid block of stainless steel.

In his 1973 sculpture Untitled, Ray tied himself to a tree branch and stayed there for several hours. The photograph of his performance is exhibited here. It most poignantly captures the figure/ground concept that Ray likes to play with.

In Figure Ground, Ray has found himself a subject matter, a unifying thought, in his abyss of variations, where Ray is constantly discovering. And we discover with him.

As I step out into the hallway of the Met, where two million works span 5,000 years of world culture, I encounter Ten Marble Fragments of the Great Eleusinian Relief that Ray copied in aluminium. I promise myself I will return and view the exhibition again. I look forward to Ray’s funny employee-of-the month photo, to collecting frog eggs with Huck, and to talking about the stars with Jim.