Vivian Maier. Self-portrait, Chicago area, June, 1978. Chromogenic print, printed in 2018, 16 x 20 in. © Estate of Vivian Maier/Maloof Collection, courtesy Les Douches la Galerie, Paris & Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York.

Les Douches La Galerie, Paris

19 January – 30 March 2019

by TOM HASTINGS

A queue of people snakes away from Les Douches La Galerie, their collars pitched against a freezing Parisian wind. As I leave the vernissage of Vivian Maier: The Color Work, I find myself picking out details on the cobbled street: an elderly couple in conversation, one of them momentarily distracted by a passing bird; three suitcases lodged against the kerb, a group of friends idling. For Maier’s images entreat the viewer to document their own surroundings.

In fact, the incitement to observe the everyday arises from the photographer’s decision-making process: the intuition the snapper brings to viewing angles, the moment of capture and wagered degrees of intrusion. Such split-second negotiations comprise the generic conventions of street photography, whose status as an art form relies on the commercial mythologisation of the – historically, predominantly male – photographer.

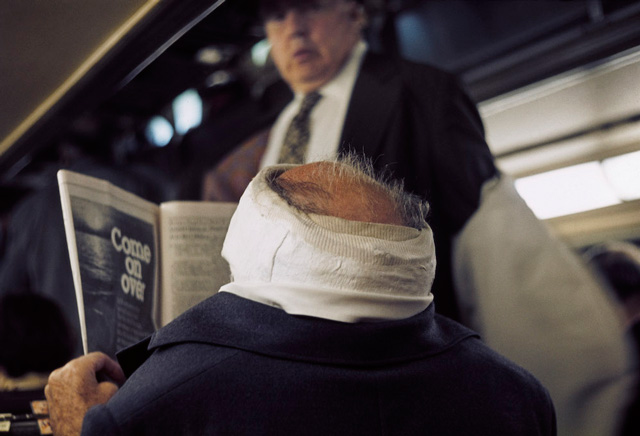

Vivian Maier. Chicago, October 1976. Chromogenic print, printed in 2018, 16 x 20 in. © Estate of Vivian Maier/Maloof Collection, courtesy Les Douches la Galerie, Paris & Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York.

Whether it be Diane Arbus or Lee Friedlander, the printed exposure is an index of the photographer’s willingness to interrupt someone’s passage, the subject’s expression – startled or affable – indicating the artist’s selected tactics. What occurred in the moments preceding the shot? Was this person accosted by the photographer, or were they conveniently left unaware? Who are we looking at? As I walk around the bustling gallery rooms, I scan Maier’s photographs, seeking traces of causality, narrative and effect that might reveal the minor transactions that surely accompanied the production of each image.

In one, a middle-aged man, hunched over, is visible through the window of a dilapidated wooden shelter. It is unclear whether he is a fatigued vendor or is merely a passerby taking a rest, for bunches of newspapers – a recurring motif in Maier’s work – are pinned to the wall outside. Bright red forms that could be petrol containers are obscured by the bottom right of the frame, hinting at a context. Scholar Pamela Bannos has noted that Maier, when she did print up her negatives, which was seldom, tended to enlarge her subject by cropping peripheral material. This editorial decision is here reinforced by the shelter’s aperture, which, coupled with its pitch-black interior, imbues the man with a distinctly painterly quality, hitching the image to a realist tradition. We are afforded just enough information to locate this person in Chicago in the 1960s or 70s, but no more.

Vivian Maier. Self-portrait, Chicago area, July, 1975. Chromogenic print, printed in 2018, 16 x 20 in. © Estate of Vivian Maier/Maloof Collection, courtesy Les Douches la Galerie, Paris & Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York.

This attention to internal framing, most properly a hallmark of Maier’s self-portraiture, is elsewhere facilitated by found mirrors. One crystalline example features Maier’s jutting reflection caught in a mirrored sheet that lies on what looks like a trestle table. The hands of her young charge – Maier spent her life working as a nanny – are isomorphic with a skyscraper that looms over both figures, cutting the sky with sharp perspectival lines. In another image, we see Maier’s reflection in a mirror that is divided into three consecutive circles and seen through the oblique screen of a shop window. The photographer’s figure is split into head, thorax and abdomen, a playful dissection that allegorises the way her life and works have been retroactively assembled and institutionally framed.

Les Douches’ third showing of Maier’s work since 2014 forms part of her continuing recognition by the art world as a major figure in photography, whose story is now legend. In 2007, two years before her death, poverty compelled Maier to sell about 150,000 negatives. The historian John Maloof took a chance on a large box of them at a “look, but don’t touch” auction. Digitally scanning several negatives, he recognised the particularity of her vision and, along with collectors, Ron Slattery and Randy Prow, went on a mission to forensically reconstruct her movements. This journey led Maloof to produce the acclaimed, though sentimentalising, 2013 documentary Finding Vivian Maier.

Vivian Maier. Untitled, undated. Chromogenic print, printed in 2018, 16 x 20 in. © Estate of Vivian Maier/Maloof Collection, courtesy Les Douches la Galerie, Paris & Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York.

Born in New York in 1926 to a French mother and an Austrian father, Maier nannied for several families in New York and Chicago. This job permitted her relative freedom, as she was able to walk the streets, children in tow, camera at the ready. As well as taking photos, she interviewed passersby on current affairs, made recordings using a dictation machine, and collected newspapers, which she hoarded away in her always-locked quarters. The intensity and obsessiveness of her practice chimes with the art museum’s historical predilection for interesting figures; indeed, the challenge of regarding her work is to look beyond the construction of her personality as an outsider artist.

Vivian Maier: The Color Work, installation view, courtesy Les Douches la Galerie, Paris.

Les Douche is well matched to the task of foregrounding the work. Located on the first floor of a repurposed building, the gallery features parquet flooring, columns surrounded by white tiles, red lacquer, fat chrome banisters and house plants situated near floating floors, and room dividers installed to display the photographs. This melange of furnishings resembles a film set, an environment suited to the medium’s address to fantasy. It contrasts with the staid interiors of Howard Greenberg, the New York Gallery from which the show has just moved, and which oversaw the accompanying monograph, published in 2018 by Harper Design and featuring a text by the curator Colin Westerbeck.

Vivian Maier. Untitled, 1976. Chromogenic print, printed in 2018, 16 x 20 in. © Estate of Vivian Maier/Maloof Collection, courtesy Les Douches la Galerie, Paris & Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York.

In its current iteration at Les Douches, The Color Work focuses on, although is not limited to, Maier’s colour prints. One side of the gallery presents the greyscale images I am familiar with, while the other showcases the recently excavated colour work – she was more interested in the act of capture and the bulk of her work was never printed. The two series are given continuity by the formatting of a standard size, positioned at eye level, and the application of black frames. These curatorial decisions provide viewers with a carousel-like slipstream, meaning we bring a similar kind of focus to each image.

Vivian Maier. Self-portrait, Chicago area, May, 1977. Chromogenic print, printed in 2018, 16 x 20 in. © Estate of Vivian Maier/Maloof Collection, courtesy Les Douches la Galerie, Paris & Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York.

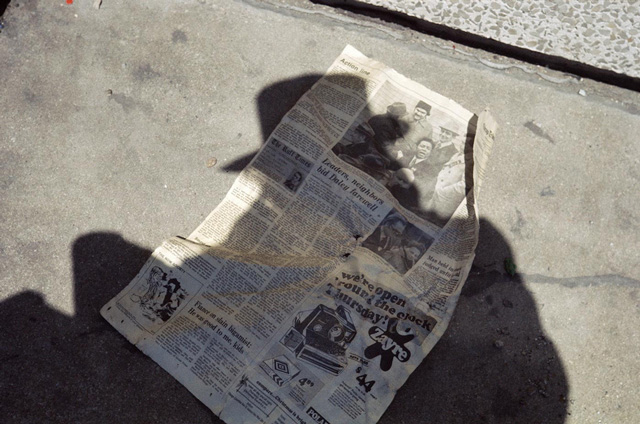

What distinguishes Maier from her peers – for she was surely conversant with histories of photography – is the variety of tactics and imagined scenarios on display. As I walk around the gallery, her shadow emerges as a key signifier, interpolating scenes ranging from a crumpled newspaper discarded by a park bench to the snowy banks of Lake Michigan and a domestic suburban fence. Caught on the medium-format Rolleiflex she used almost exclusively after 1953, four years before moving from New York to Chicago, her shadow, like the mirror, begins to describe a rule-bound logic. I discern the working through of certain interests: shoes and tights captured from behind at ground level; the silhouette of a back, whether clad in a suit or revealed by a swimsuit; the ironical sadness of happy things such as pastel-coloured balloons and a community noticeboard, and the regularised movements of blue-collar workers.

This material, which represents the stratified conformism and vulnerability of cold war-era American life, is finally what stops Maier from becoming a Netflix industrial product. At the same time, her social position infiltrates The Color Work, so that what we see is a record of her waged and gendered movements. That these prints were posthumously exposed and assembled by curators and gallerists finally sanctifies their status as documentary evidence, in a way that perhaps eludes the work of her “professional” peers.