The Honest Eye: Camille Pissarro’s Impressionism, installation view, Museum Barberini, Potsdam, 14 June – 28 September 2025.

Museum Barberini, Potsdam

14 June – 28 September 2025

by SABINE SCHERECK

Camille Pissarro is no blank sheet and, as one of the founders of impressionism in France, his name is frequently cited alongside others of this movement, such as Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Edgar Degas. Yet, this ignores the fact that he was the odd one out: he was not born in France, he had no formal training in art and, in contrast to his contemporaries, he stuck to impressionism and maintained his independence rather than conforming to the established art business in France. It was his rise as an artist outside academic circles that enabled him to develop this new style free from conventions.

The Museum Barberini now presents a fresh perspective on his unique position within French art in the exhibition The Honest Eye: Camille Pissarro’s Impressionism. By bringing together more than 100 works from 50 international collections, Pissarro’s range of motives becomes evident – stretching beyond the idyllic landscapes for which he is best known.

The exhibition begins by taking the visitor to his artistic roots in the Caribbean and South America. The wall colour, a pale earthy sand tone, is finely tuned to the palm trees and tropical scenes of Pissarro’s images. It feels like landing on an exotic shore, where the lightness of a summer holiday and the sense of adventure and excitement of exploring a new place fill the air. Among them is the watercolour Pariata (1853), which depicts a small hut under lush foliage. The simple life of the ordinary people captured Pissarro’s imagination. Equally enchanting is the drawing La Guaira (1853) showing from a distance a small group of women carrying water on their heads and engaged in conversation. There is a lot of warmth and dignity in his rendition.

Camille Pissarro, Landscape, Saint Thomas, 1856. Oil on canvas, 47.63 x 38.1 cm. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond. Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon.

© Sydney Collins, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts.

This type of environment shaped him early on. He was born in 1830 on the island of St Thomas, now the US Virgin Islands but at that time part of the Danish West Indies. His father was a merchant of Portuguese Jewish origin and held French nationality. Pissarro grew up in a multicultural milieu and was sent to boarding school in France, where he developed an interest in French art and received his first lessons in drawing and painting. When he returned to the Caribbean, he joined his father’s business and worked as a clerk at the port. Yet, he continued to pursue his passion for drawing. He met the Danish artist Fritz Melby, who became a mentor and friend and encouraged him to take up art professionally. When Pissarro was 21, they travelled to Venezuela, where they worked as artists.

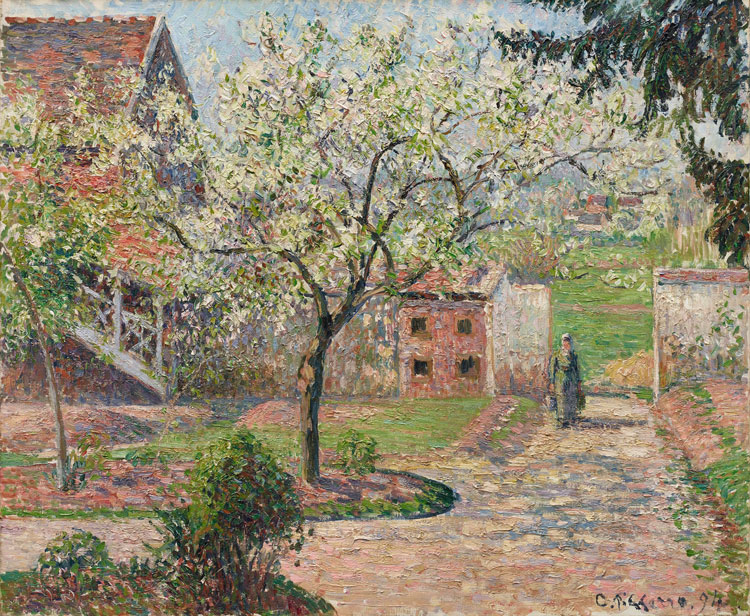

Camille Pissarro, Plum Trees in Blossom, Éragny, 1894. Oil on canvas, 60 x 73 cm. Ordrupgaard, Copenhagen. © Heritage Images / Fine Art Images / akg-images.

In this early period, he already shows his affinity for peaceful, rural scenes. In 1855, the next step in his career was to relocate to France, where the plein-air painting of the Barbizon School further informed his work. The paintings here, paving the way to impressionism, show vast green fields, trees and hills, often against a cloud-covered sky. They are everyday scenes that emanate a pleasant contentment in which the world is at peace with itself. The few people included seem like a natural part of the scene, such as in The Thaw or The House of Monsieur Musy, Louveciennes (1872). It has an intriguing atmosphere with the muddy earth, in parts still covered in snow, while the trees bear remnants of autumn leaves and the sky already lifts the spirit with a bright blue shimmering through the clouds and heralding spring with its overall pastel tones. The painting Pontoise (1867), the name of the village to which he had moved a year earlier, shows a man and a woman cultivating a large vegetable garden. The wall colours of these sections of the exhibition reflect his artistic transition to European landscapes comprising earthy tones, sometimes darker, sometimes brighter by adopting a darker, richer, yet unobtrusive shade of brown. It is worth picking up this detail of wall colour that usually goes unnoticed, yet contributes, however subtly, to the overall perception of the works.

Camille Pissarro, Spring at Éragny, 1890. Oil on canvas, 65.4 x 81.6 cm. Denver Art Museum, Frederic C. Hamilton Collection, bequeathed to the Denver Art Museum.

© William O’Connor, Denver Art Museum.

The draw of Pissarro’s works lies not just in the authenticity with which he brings out the simple beauty of nature, but also in his quiet delight in the myriad atmospheres that winter, spring, summer and autumn can conjure up – all this combined with the different moods produced by the time of day and the weather. Examples of this are View of Bazincourt, Snow Effect, Sunset (1892) and Autumn, Poplar Trees, Éragny (1894). In both of these, the sun is spreading its light over the horizon, filling the sky with warm and lively pastel tones. Yet, there is a major difference in style. While the first is composed of long brushstrokes with thick paint, the latter, with its filigree application of colour, already hints at pointillism. That is even more evident in Meadow at Éragny with Cows, Fog, Sunset (1891) with its strong colours and iridescent sky, in which you could lose yourself. It is not a picture you would immediately assign to Pissarro, and the influence of the younger painters Georges Seurat and Paul Signac, who championed pointillism, is clearly visible. Yet, despite experimenting with this new style, Pissarro returned to his familiar impressionism, a freer, less laborious style of painting.

Camille Pissarro, Avenue de l’Opéra, 1898. Oil on canvas, 73.3 x 92.3 cm. Musée des Beaux-Arts de la Ville de Reims. Bequest of Henry Vasnier, 11/1907. © Christian Devleeschauwer.

Besides the numerous depictions of landscapes, one section is devoted to people working in the fields. It shows variations of stylised women collecting hay and buying and selling produce at a bustling market. Another section takes the visitor to Paris, where the wide streets, with their flow of people and carriages leading into the distance, become echoes of rivers such as in Avenue de l’Opéra (1898) or The Pont Neuf (second series) (1902). As in his images of nature, there is a sense of poetry in his views of the city as in The Louvre, Morning, Spring (second series) (1902), which rejoices in pastel colours. It makes you think of a leisurely morning walk, when you stand still for a moment to take in the undisturbed beauty of this scenery, in which trees sport fresh green leaves signifying new life, the river flows gently, the museum buildings form a calm presence in the distance and the vast bright blue sky with soft white clouds opens up above it all.Between the years 1893 and 1903 he left his home in Eragny-sur-Epte to spend extended periods in Paris. But he also travelled to Rouen, Dieppe and Le Havre, where he observed the busy ports – a setting with which he was familiar, having worked as a teenager at the port in St Thomas.

Camille Pissarro, The Louvre, Morning, Spring, 1902. Oil on canvas, 64,8 x 54 cm. © Hasso Plattner Collection.

But not everything revolves around France. During the Franco-Prussian war in 1870-71, he moved to London. Unlike Monet who was mesmerised by views of the Thames within the cityscape while there, Pissarro was drawn to more pastoral areas such as Dulwich and Kew. During his stay in Britain, Pissarro also studied the works of John Constable and William Turner. Both artists clearly resonated with him, Constable for his depictions of atmospheric landscapes and Turner for his innovative way of representing light, particularly glowing sunlight.

Camille Pissarro. Jeanne Pissarro (Minette) holding a Fan, 1873. Oil on canvas, 55 x 46 cm. The Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford. Bequeathed by Esther Pissarro, 1952.

The exhibition also comprises portraits of family members, of which only a few exist. They a glimpse into his private life and are a cue to taking a closer look at the man behind the art, fascinating, warm-hearted and down-to-earth. Being well-to-do, his parents disapproved of his marriage to Julie Vellay, a wine-grower’s daughter who had been employed by his family as a maid. They married in Croydon in 1871 and had a happy union that produced eight children. It was a harmonious relationship and when Pissarro struggled to sell his work, for example, it was his wife’s cultivation of a vegetable garden that tided them over. This was crucial when the couple returned to their home in France after the war and found that Prussian soldiers had destroyed more than 1,000 works that he had done over a 20-year period. He was left with hardly anything to sell, a situation that was already difficult because his uncommon style had not yet found a following.

Camille Pissarro, Hoar-Frost, Peasant Girl Making a Fire, 1888. Oil on canvas, 92.8 x 92.5 cm. Hasso Plattner Collection, Museum Barberini, Potsdam.

His wife’s strong connection to rural life and work certainly shaped Pissarro’s view of nature and those working with it, leading him to portray farmers and labourers with great dignity. In this respect, he shares very much the same values as the German impressionist Max Liebermann, who also portrayed farmers, shepherds and working women in a quiet, respectful way and in harmony with their natural environment, particularly when you look at the works he created during his stays in Holland. Interestingly, he, too, came from a middle-class Jewish background.

Besides his socialist leanings, Pissarro was also a good networker, bringing fellow artists together and supporting a younger generation. As his works were repeatedly rejected by the Paris Salon, along with those of Monet and Degas, he and his fellow artists founded the Société Anonyme des Artistes Peintres, Sculpteurs, Graveurs in 1873 to enable them to showcase their work. It brought attention to their new artistic style, which became known as impressionism. The group organised eight exhibitions between 1874 and 1886; Pissarro was the only one who took part in all of them. In addition, having already travelled widely before settling in France, he added a cosmopolitan component to the impressionist group.

This illuminating and comprehensive exhibition was curated by impressionism expert Claire Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, Nerina Santorius from the Museum Barberini and Clarisse Fava-Piz from the Denver Art Museum.

• The Honest Eye: Camille Pissarro’s Impressionism will be at the Denver Art Museum, Colorado, from 26 October 2025 to 8 February 2026.

Camille Pissarro, Boulevard Montmartre, Twilight, 1897. Oil on canvas, 54 x 65 cm. Hasso Plattner Collection, Museum Barberini, Potsdam.