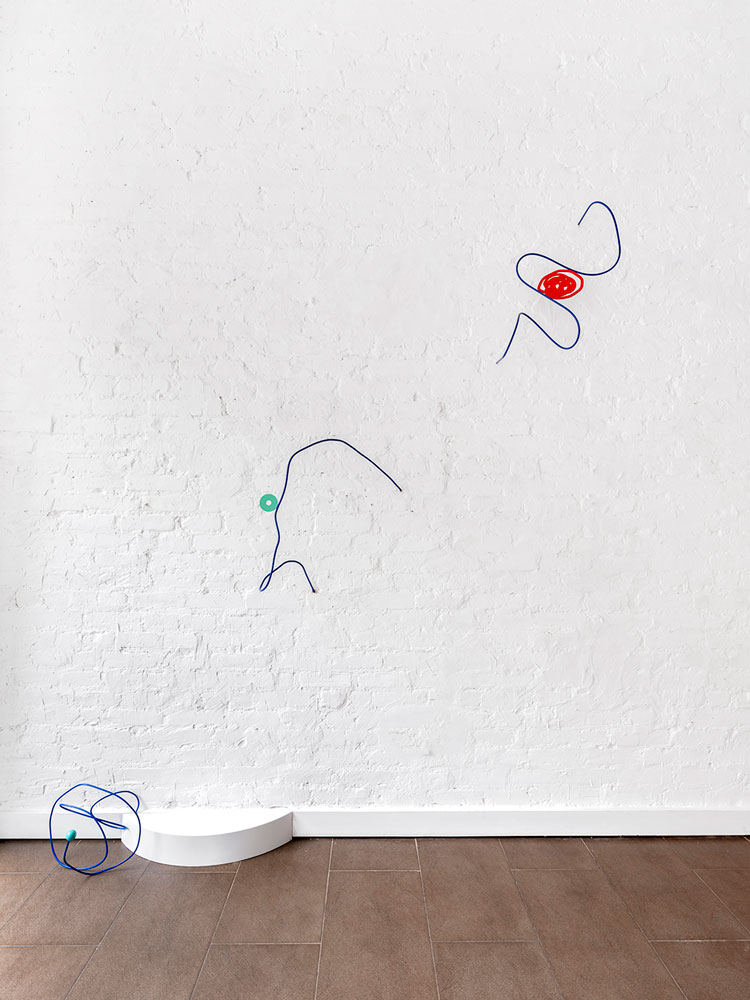

Material Resistance: Anna Barlik, Marlena Kudlicka, Magdalena Abakanowicz and Agnieszka Kurant, installation view, Nguyen Wahed Gallery, New York, 2025. Photo courtesy Nguyen Wahed Gallery.

Nguyen Wahed Gallery, New York

12 September – 28 November 2025

by YASMEEN M SIDDIQUI

If not for video documentation from Magdalena Abakanowicz’s Butoh – Dance – Sculpture (1995), of painted bodies in motion, I might not have registered a chain that connects Marlena Kudlicka’s columnal work, Anna Barlik’s sculptures piercing into brick walls, and Agnieszka Kurant’s Sentimentite that bellows capital and innovation with a nod to the material world, minerology and histories timestamped by the long ago, and the seemingly increasingly irrelevant Occupy movement. Those formal aspects of Material Resistance are further inflected with eerie context. The show’s opening reception took place on 10 September, the day Russian drones entered Polish airspace and struck a house, sending shock through the region. This context for this exhibition of two sculptures, a video and a non-fungible token (NFT), by four female Polish artists, is not conspiratorial. Rather, it is indicative of our volatile moment, each day ringing in surprises with their shocks.

Left and right: Marlena Kudlicka, Black Discrete 00 and Black Discrete 01, 2025. Powder coated steel, each 90 3/5 × 11 4/5 × 11 4/5 in (230 × 30 × 30 cm). Installation view, Nguyen Wahed Gallery, New York, 2025. Photo courtesy Nguyen Wahed Gallery.

On entering, the door is flanked by Kudlicka’s sculptures hanging from the ceiling; virtually identical matte black powder-coated steel chains of symbols dropping without hitting the floor. They create an almost decorative frame for Kurant’s rotating digital rock on a monitor on the far wall – a rock spinning in a frame of words. There is a snap of colour to the right, to the left and pierced into the gallery’s walls, extending Barlik’s long practice that engages architecture and responds to space. Wounding the wall, Barlik’s work is not affixed seamlessly: there is an oozing, a mucus-coloured seeping, perhaps from a glue or fixative. This messiness belies a surprise considering the otherwise formal playful primary-coloured balls strung on twisting gravity-defying cables, that look like deconstructed abaci. Abstracted geometries extracted from public spaces is a feature of Barlik’s work, in general – skate parks with their planes and slopes, a recent body of work, reminds me of her varied uses of geometries.

Kudlicka’s Black Discrete 00 and Black Discrete 01 (both 2025) look like equations pulled into three dimensions, yet something is always off, angles don’t quite meet, alignments slip, balance is unsettled. They register as systems designed for precision but tipped into error, as though order had been unwritten. This skew resonates with the logic of blockchains that have emerged as a major monetary system. Each block is singular, sealed, guaranteeing the integrity of a network that disperses control. But in that very dispersal lies the loophole: a system built to resist oversight becomes the ideal channel for money that must move invisibly, financing all sorts of enterprises: weapons, drugs, human trafficking. Kudlicka’s forms in this space evoke thinking about how the promise of perfect security coexists with the possibility of exploitation.

Works by Anna Barlik, installation view, Nguyen Wahed Gallery, New York, 2025. Photo courtesy Nguyen Wahed Gallery.

Last year, I visited Warsaw, a trip organised and funded by the Polish Cultural Institute New York, which also supported this exhibition. I had seen Barlik’s work on that trip and gained an introduction into how culture and art are activated in constructing national identity.

Abakanowicz’s film documentation of Butoh – Dance – Sculpture (1995), here exhibited for the first time outside Poland, is a collaboration brought together with the Tokyo-based Butoh troupe Asbestos, led by Akiko Motofuji. It was shown in Warsaw’s Agrykola Park alongside the opening of her exhibition at the Centre for Contemporary Art in September 1995. Drawing on her sculptural series Backs, Embryology, Seated Figures and Mutants, Abakanowicz produced drawings that Motofuji and her dancers translated into choreography, accompanied by bassist Tetsu Saito and two kotos, a plucked half-tube zither that is the national instrument of Japan. Abakanowicz subtitled the event Alteration of Alterations, describing the dance as a work that would bring her sculptures’ static forms into motion. Documentation of those rust-coloured dancing bodies, screened at almost life size in the glass-faced, modestly sized gallery, around the room.

What strikes me looking at this piece three decades since it was first shown is that we cannot ignore how it speaks to Poland’s continuing reckoning with the second world war, a reckoning that often takes the form of deflection. Abakanowicz turned to Hiroshima and to Butoh, a form born in the wake of Japan’s postwar devastation, as a vehicle for mourning. Yet the catastrophe closest at hand, the annihilation of Poland’s Jews, who had lived in the country for 1,000 years, is displaced. The inclusion of this work in this show infers a certain political agenda. The performance acknowledges tragedy, but it is tragedy transposed elsewhere, on to another nation’s body. By turning to Japan as a foil, Abakanowicz draws connections among multiple atrocities. The result is a requiem that is also an alibi. The “dance of darkness” offers a profound vocabulary of grief, but here it functions as cover, as if another culture’s mourning could stand in for the unspeakable erasures at home. In this way, Butoh – Dance – Sculpture is not only a collaboration between sculpture and movement, and a collaboration across nations and tragedy; it is also a choreography of memory politics, circling grief while refusing to name the absence that haunts Warsaw itself.

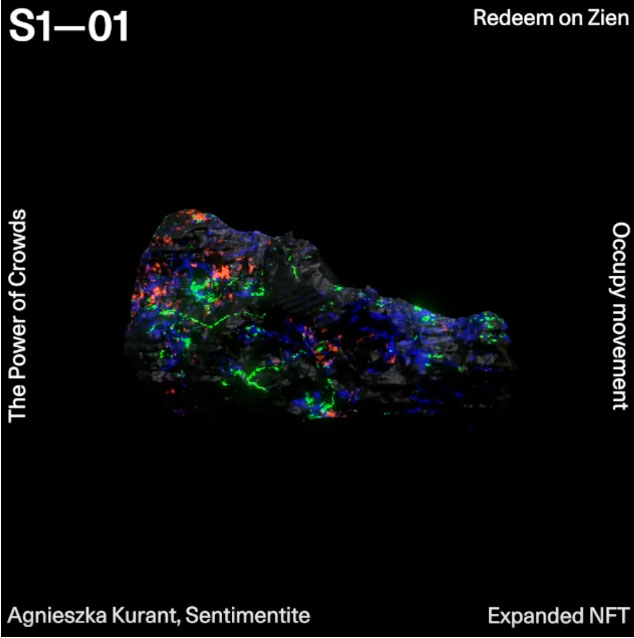

Agnieszka Kurant, Sentimentite, 2022. Image courtesy Nguyen Wahed Gallery.

The show’s purview zooms in and out. Kurant’s digital work at the back of the room spins locations and people – participants in the global Occupy movement – into a shape that looks like a rock. In other spaces, museums perhaps, I understand there is an object, a sculpture, owned by someone, a collector. But for us here it is a shape, a digital model framed with the following words: “S1-01 – Redeem in Zien – Occupy Movement – Expanded NFT – Agnieszka Kurant, Sentimentite – The Power of Crowds”. What is Zien – does it mean to see? Does she ask us to look? Who is this crowd? What power is leveraged, and to what end?

Kurant’s deployment of NFTs is at once visually plain, almost naive and conceptually pointed. By rendering the crowd as geology – an inert, mineral form – for me, this links the primordial materials of the Earth to the blockchain economy, its extractive roots: mining for energy, for capital. The irony is sharp. A technology heralded as immaterial and liberatory is exposed as destructive, tethered to the same cycles of resource extraction and speculation it claims to transcend. At the same time, Kurant recalls the paradox of the crowd itself: historically feared as unruly, dangerous, and populist, here is aligned with a progressive movement. That tension – between collective power as emancipatory force and as peril – echoes through her work, and throughout the show, making clear the unresolved contradictions of the politics of mass mobilisation.