Marisa Merz: Listen to the Space, installation view, LaM museum, 3 May – 22 September 2024. Photo: F. Iovino / LaM.

LaM, Lille

3 May – 22 September 2024

by TOM DENMAN

The human head normally conjures up notions of the brain, the mind – often in contrast with the heart. Because of its density, it is considered heavy. Marisa Merz’s heads are like angels, light and yet metaphysically immense. There are numerous heads in this show, which opens with a cluster of them. On plinths of varying height – often, as a result, balletically evading an encounter a quattr’occhi – these smaller-than-life-sized, wounded forms are mostly made of unfired clay, painted or leafed over with blotches of gold, on the lips, lining a fissure where the skull has cracked. Some have copper netting pinned to them, as if they had washed ashore. Their fragmentation gives them an archaeological quality, or one of geological accident – as if the horizontal, seemingly burnt-out cavern that forms the eyes in one example were formed by something other than human artifice. Equally, we can imagine the thumb that formed the characterful twitch in its fulcrum as having had a particular face in mind.

Marisa Merz, Untitled, 1983. Bronze with paint, 20 x 20 x 25 cm. Collection Merz. © Adagp, Paris, 2024. Photo: Renato Ghiazza.

This is the first solo exhibition of work by the Italian artist to be held in a museum since her death in 2019, the first in France in 30 years, and the first in which she has not taken part in the curation. Without Merz’s input, the task of putting on such a show is a daunting one, not least since she would often make on-site curatorial decisions that could alter the effect of her works quite dramatically. She refused to give clear verbal explanations of her shapeshifting works and remained wary of the fossilising effect of titling and dating them. The curators – with the assistance of her daughter Beatrice Merz – have essayed to channel the artist’s extemporaneity. Thus, they have eluded chronology and created a dynamic of atonal, seemingly improvisational relations (helped by the asymmetries and unexpected sightlines of the gallery’s architecture), while expanses of white space complement Merz’s angelic, whispering lightness.

Marisa Merz: Listen to the Space, installation view, LaM museum, 3 May – 22 September 2024. Photo: F. Iovino / LaM.

Two gold heads are collaged on a cream, vertically aligned sheet of paper, itself bulldog-clipped to a board. One could be teetering on top of the other, or they could both be tumbling, in mid-fall. At the same time, the upper, smaller head is flanked by spray-painted, wing-like lines, evoking resistance to any downward movement – or is it upward? There is something affecting about the bond between them, maybe because it recalls the myth of Daedalus and his son Icarus, who met his end by flying too high with the wings his father made for him. Entering the next room, another version of this work is the first thing you see, on a parallel wall – such that, from the right viewpoint, both can be seen at once – except these heads are suspended by the black background in a state of zero-gravity calm. Dead? Transformed into a constellation? Merz leaves such questions open, just as the narratives her work proliferates in the viewer’s mind are endless and contingent.

Marisa Merz, Untitled, undated. Mixed media on paper, copper wire, 150 x 209 cm. Collection Merz. Courtesy Fondazione Merz - Gladstone Gallery, New York - Thomas Dane Gallery, London © Adagp, Paris, 2024. Photo: M3Studio.

Like these collages, many of Merz’s works bear traces of the studio, materially suggesting a state of perpetual mutability and mobility. Pins and clips hold them together; some works are unframed, some leaning against the wall as if waiting to be hung. Paperclipped to the edge of a monumental drawing from 2010 is a note, “L’annuncio dell’angelo” (The announcement of the angel), which acts less as a label or a title than as a reminder for the artist. It thus refuses completion – as if the splintering folds from which the spiritual being emerges were to continue folding and unfolding.

An archival section displays photographs documenting the varying ways Merz installed her works. Scarpetta (Little Shoe) (1968), for instance, often appeared as a multiple, in a sequence on the floor or worn on the artist’s feet. In a photograph taken on the beach at Fregene (near Rome) in 1970, a pair of these nylon-netted slippers is artfully positioned on the sand, as if it had emerged from the sea. In this show, the work appears in the singular, affixed to the wall on a vertical axis, its organicism resonating with the giant, uterine copper wire sculpture on the wall in another room (which, on other occasions, has been laid on the floor). Indeed, Venus was born of ocean spume, and here the archetypical association between the female form, the sea and reproduction is felt as a nexus of endless, spontaneous creativity.

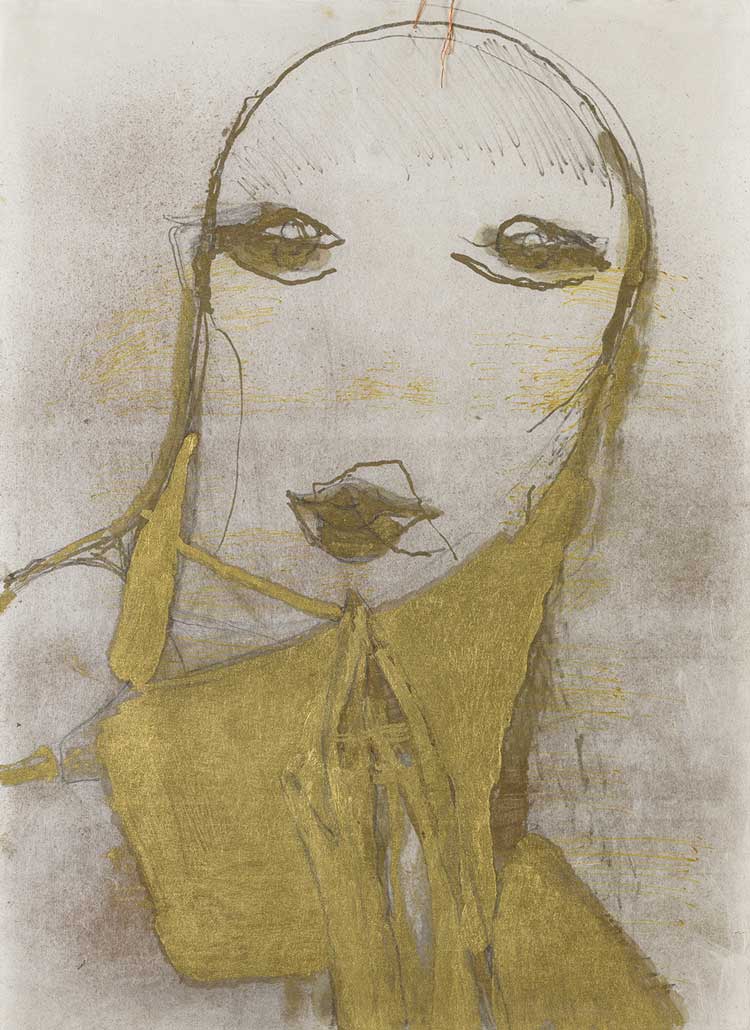

Marisa Merz, Untitled, undated. Mixed media on rice paper mounted on a Plexiglas frame; 45.5 x 32.5 cm. Private collection, Paris. Courtesy Etienne Bréton / Saint-Honoré Art Counsulting. © Adagp, Paris, 2024. Photo: Boris Kirpotin.

The recurrence of motifs from the early history of Italian art, all of which seem to stem from deep recesses of cultural memory, warrants this mythological reference. In a catalogue essay, curator Sébastien Delot offers a way into the palimpsestic nature of Merz’s practice via classical mnemonic theory – resuscitated by medieval thinkers such as St Augustine and Dante – which posited memory as a spatial and image-based phenomenon. It seems to me that Merz’s myriad pencil, charcoal and pastel drawings of heads – here represented in two separate clusters – without being illustrative as such, relate to this. They recall a well-known drawing Leonardo da Vinci made of a section through a human skull (1490-93), which united empirical vision through the eye with the faculties of memory and imagination. As embodiments of unbounded autopoiesis, swirling, swelling and transmogrifying beyond their confines, it might be said that Merz’s drawings animate the psychological principles of the Renaissance polymath’s diagram.

Marisa Merz, BEA, 1968. Nylon threads, steel knitting needles, 40 x 90 x 5 cm. Collection Merz. Courtesy Museum der Moderne, Salzburg © Adagp, Paris, 2024. Photo: Rainer Iglar.

Merz’s work radiates complex, often conflicting emotions. These seem to stem not from any facial or artistic expression, but from the soulful contact they manifest between one person and another. In one painting, a cosmos of faces swirls. One of them seems to recreate itself by blowing a bubble – and so the two faces are kissing. At the foot of the image, a black slab, resembling the lid of a grave, has shifted to let loose groping, skeletal arms, which at once embrace and entrap. Bea (1968) spells an abbreviated version of her then eight-year-old daughter’s name – rendered in dark tones of nylon thread, with bent, defunct knitting needles skewering the letters to hold them in place. A small, cuboidal head made of clay, and with the features naifly applied in red paint, is deeply affecting in its simplicity. A smudge to one side inserts a kissing profile – like one of Picasso’s facial distortions, except the presence of the secondary head is less delineated, a ghost. One eye has collapsed inwards. It is the love that binds, that holds someone so close you might destroy them, that leaves an indelible mark that is also a disfigurement.

Marisa Merz, Untitled, 1977. Table, copper wire, metal rods, spathiphyllum (monocot), dimensions variable. Private collection. © Adagp, Paris, 2024. Photo: Mario Corti.

For decades it was believed that the photographs taken at Fregene were a performative adjunct to Germano Celant’s pioneering exhibition, Arte Povera + Azioni Povere, held in the Arsenali d’Amalfi in 1968 (at which Merz’s presence is poorly recorded, having been invited to participate at the last minute, with one work, Bea). In the catalogue to the current show, Andrea Viliani [the director of the Museo delle Civiltà in Rome] suggests that the artist refrained from correcting this generally held assumption out of a preference to avoid the finality of the archive. Aside from the gendered bias of the time, the impossibility of pigeonholing Merz might be why she has received significantly less attention than her Italian contemporaries (not to mention her husband, Mario Merz), a predicament that only began to be rectified when the Venice Biennale awarded her a Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement in 2013 – which she then recreated out of unfired clay and copper wire (Untitled, 2013). Although she did not make overt feminist statements in her work, she invented her own path as a woman involved but not formally included in the male-dominated movements of her earlier years; both at the centre and in the gaps, in the seams, reclaiming this subject position as one of tricksterish ethereality.