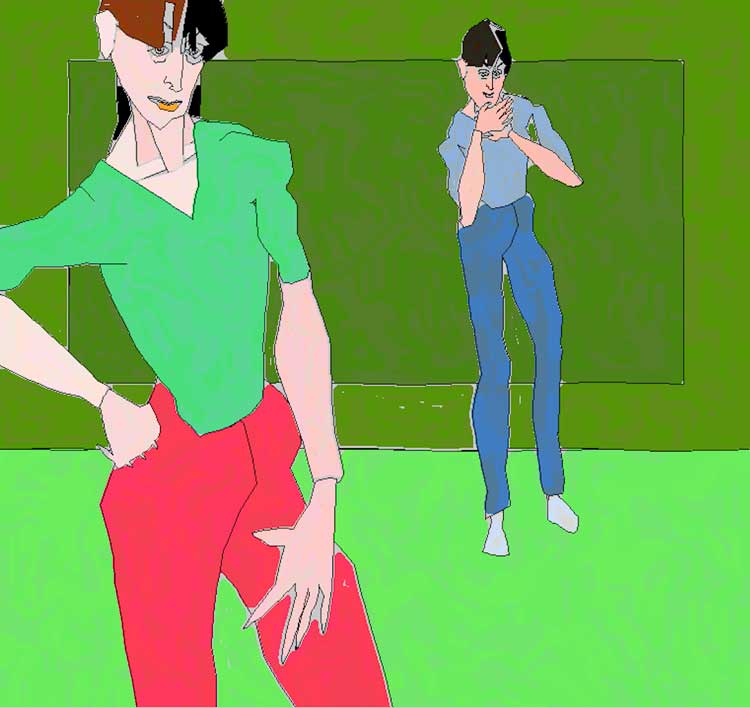

Harold Cohen: AARON, installation view, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, 3 February – 19 May 2024. Photo: Ron Amstutz.

Whitney Museum of American Art

3 February – 19 May 2024

by LILLY WEI

AARON – the talented Mr AARON? – is an artificial intelligence (AI) program that generates imagery, developed by the pioneering British artist Harold Cohen (1928-2016) in the late 1960s. It is one of the earliest, and most complex programs of this kind: Cohen called it his doppelganger. And although, in some recountings, it was named after Moses’ brother, who was considered the more eloquent sibling and, for a time at least, was appointed by God to speak for Moses, it is not a robot as we might imagine a robot, not a blinking, beeping, twirling (and adorable) R2-D2, say. It is software, and essentially disembodied, operating via plotters, pens, colours and a computer.

Harold Cohen, AARON KCAT, 2001. Screenshot. Artificial intelligence software. Dimensions variable. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase, with funds from the Digital Art Committee 2023.20. © Harold Cohen Trust.

The art on view at the Whitney Museum’s survey, Harold Cohen: AARON, is billed as a joint effort, “a collaboration,” in the words of its (human) progenitor, although it gets complicated as to who is credited with what, provoking countless questions about creativity, originality, authorship, the nature of art and how AI, the hottest topic around, might alter how we think about endeavours we formerly considered to be strictly human. Yet Cohen, for all his excitement about the potential of AI in those early, blue-skied days of technological breakthroughs and beneficences, understood that AARON was a tool, a high-functioning mechanism that he dedicated himself to refining over a lifetime, its knowledge based on what he was able to encode. It was not autonomously inventive, despite his deliberate intertwining of their artistic and professional identities, which included exhibiting with AARON at museums, galleries, and science institutions around the world.

Harold Cohen, AARON Gijon, 2007. Screenshot. Artificial intelligence software. Dimensions variable. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase, with funds from the Digital Art Committee 2023.21. © Harold Cohen Trust.

Cohen wanted to emulate the cognitive steps taken by a painter, but that painter was ultimately himself. As critics have pointed out, he was modelling only his own artmaking processes. Yet it is closer to human creative methods and is not text-prompted like currently popular AI software DALL-E or Stable Diffusion, image generators that have access to enormous data banks of existing images, a technology brandished by Refik Anadol in Unsupervised, the crowd-pleasing, continuously morphing visual extravaganza drawn from New York’s Museum of Modern Art’s extensive collections, or more quietly – and also more hauntingly – the acclaimed American film director Bennett Miller’s foray into AI and prints at Gagosian. AARON, on the other hand, is system-based. Cohen did not designate precise forms. The results are consequential, branching, based on what came before, similar in manner to a human painter who adds brushstrokes and lines one by one, adhering to formal rules of composition, colours and shapes, and sensitive to scale and placement. Since he described it as a collaboration between himself and AARON, he did not issue specifications, but patterns and lines that would be based on AARON’s accumulating decisions, and not predetermined. He also encoded criteria that allowed AARON to evaluate the success of a composition as well as the ability to remember what worked and what didn’t, all of which seems remarkable, especially to a non-programming geek. Several notebooks show Cohen’s sketches of his translation of human dynamics into code: postures to assume; positioning of arms, legs, heads, hands, feet; where figures and objects should be placed, and much more. Plotters in one gallery execute drawings to demonstrate AARON at work.

Harold Cohen, AARON KCAT, 2001. Screenshot. Artificial intelligence software. Dimensions variable. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase, with funds from the Digital Art Committee 2023.20. © Harold Cohen Trust.

The exhibition at the Whitney of paintings, works on paper and projections offers a kind of tutorial in Cohen’s utopian first-generation image-generating experiment that spanned more than four decades. He was an abstract painter of renown in the 1960s who had shown at the Tate and Whitechapel, and represented Great Britain at Documenta in 1964 and the Venice Biennale in 1966. But despite that, disenchanted with painting, he emigrated to California in 1968 and the University of California San Diego, lured by a one-year teaching job that ended up lasting nearly 30 years, eventually becoming chair of its art department and the director of its Center for Research in Computing and the Arts, which he also founded. Once there, he taught himself how to work with computers and began to play with robotic drawing, developing AARON when at a residency at Stanford University’s Artificial Intelligence Laboratory in 1973-75. It became the focus of his practice until his death, his research a singularly intensive, long-term study about human creativity as he steadily, laboriously transformed artistic process into code.

AARON began as a program that made freeform drawing, squiggles that looked like spontaneous markings made by hand, inspired by how children drew images, and by the mysterious images of petroglyphs he saw in northern California in 1973, intrigued by the meanings he believed once existed in them that were now lost. The show, from the Whitney’s collection, threads through Cohen’s progress as he incrementally increased the software’s complexity (as computers and his own expertise evolved), adding to its repertoire and sophistication.

Harold Cohen, AARON KCAT, 2001. Screenshot. Artificial intelligence software. Dimensions variable. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase, with funds from the Digital Art Committee 2023.20. © Harold Cohen Trust.

The works are meant to be produced as drawings and paintings, as well as to be displayed on monitors and as projections. Eventually he was able to endow AARON with figurative skills. By the 1980s, it could generate rocks, plants, human figures, and place them in a spatial context, the appealing works of this period the most richly configured: still lifes, lush exteriors, cheerfully furbished interiors, crowds, people in bright clothing. Soon, colour was added to AARON’S capabilities. Yet the figures, distinctive but flat, cartoon-like, their bodies often too schematic, awkwardly posed, looked more illustrative than otherwise and curiously unsettling, even off-putting. In Coming to a Lighter Place (1988), and a series that recalled Cézanne’s Bathers, the many-figured compositions are ambitious, but still have the sense of mechanised or electronic reproduction. The line, when regarded close up, did not have the sweeping fluency or charm of the human hand, of a Matisse, for instance, whom some of the linear portraits seemed to be channelling. Hands and feet are often simply notations, a weak point, but then, Rembrandt didn’t do such a great job with hands either. Yet there are still lifes that are delightful, and the works that Cohen painted are animated by texture, touch, and the glow of colour, and better for it, so human artistry isn’t obsolete yet. By the 2000s, Cohen/AARON returned to abstraction in works such as AARON Gijon (2007), a projection that focused on foliage that flowered and transformed in front of your eyes, a visually exuberant celebration of natural abundance, the palette, however, as it does throughout the exhibition, emitting colours that are more artificial than natural.

Harold Cohen, AARON KCAT, 2001. Screenshot. Artificial intelligence software. Dimensions variable. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase, with funds from the Digital Art Committee 2023.20. © Harold Cohen Trust.

Cohen, in his deliberations, thought that AARON might give him a certain immortality, as it could continue to turn out Harold Cohen/AARON works in perpetuity, at least theoretically. It is poignant, then, to see the dates of birth and death for Cohen on the signage, while AARON is designated only by a birth date, with a dash, in case. “I think the crux of creativity is self-modification,” he said, in 2005 in Canada’s the Globe and Mail. “If we measure creativity in terms of the output, my program generates 50 or 60 brilliant images every night when I leave it running.” Cohen concludes: “[If] you’re measuring creativity in terms of the quality of the output, then Aaron is clearly very creative indeed.” Like any proud parent, he had a proprietary stake in his “other self ”, his son, his evaluation of AARON’s gifts not, perhaps, unbiased.

Coinciding with Harold Cohen: AARON, Gazelli Art House, London, presents Harold Cohen: Refactoring (1966-74), 3 February - May 2024.