reviewed by Janet McKenzie

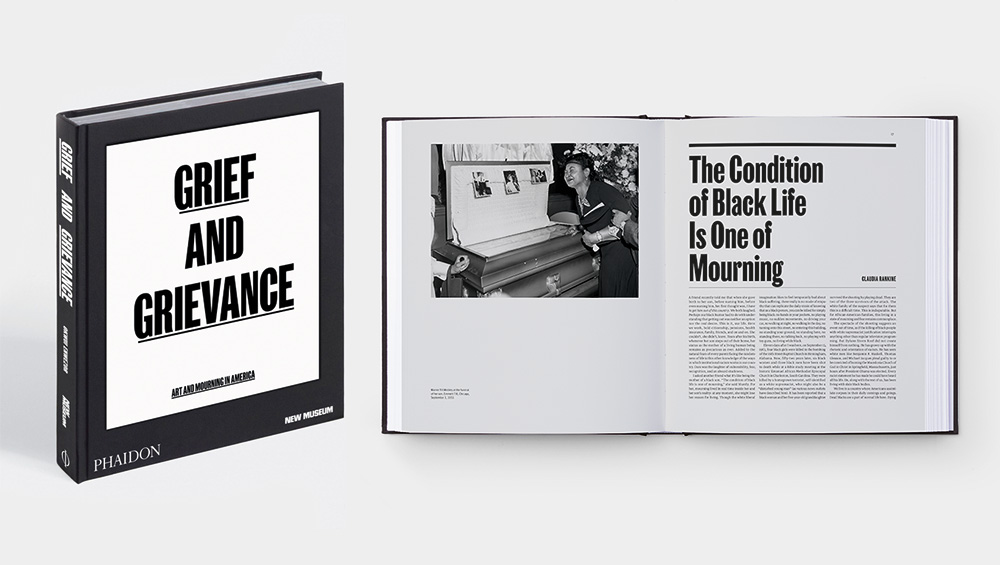

Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America is published by Phaidon, ahead of an exhibition of the same name at the New Museum, New York. The timely publication addresses the complex phenomenon of racism in the US and, in doing so, the events of recent history and the turbulent present can be understood and interpreted with fresh poignancy.

The exhibition and publication are the brainchild of the influential and visionary Nigerian-born curator Okwui Enwezor, whose untimely death in 2019, at the age of 55, has led to the project becoming, in one sense a posthumous one. The period between his death in March 2019 and the launch of the book in January 2021 has seen events that will reverberate in US society for years to come. In 2020, following the police killing of George Floyd, the Black Live Matter demonstrations escalated across the US, but also in countries around the world. The Biennale of Sydney that year was already dedicated to the theme of racial reconciliation and healing, with its first Indigenous artistic director, Brook Andrew. It challenged accepted orthodoxies to champion the work of indigenous art.

Enwezor’s large-scale exhibitions in Europe, Africa, Asia and the US displaced European and American art from its central position. His 2002 edition of Documenta was a testament to his vision. More than half of his Documenta’s 117 artists and groups were selected from Africa, Latin America and Asia. He also curated the 2008 Gwangju Biennale in South Korea, the 2012 Paris Triennale and the 2015 Venice Biennale changing the manner in which international contemporary art was presented and understood.

In 2011, he was appointed director of the Haus der Kunst in Munich, where he helped to organise the major exhibition Postwar: Art Between the Pacific and the Atlantic (2016-2017). As editor of the magazine Nka, which focused on the examination of contemporary African and African Diaspora art within modernism and postmodernism, he challenged the pejorative view of contemporary African art, and led global debate on art and postcolonialism. His conception of Grief and Grievance is the product of years of scholarship, cultural authority and passion. He assembled around him artists and curators who have carried forward his vision to create a vital and challenging project of substance and urgency.

Glenn Ligon, A Small Band, 2015. Neon, paint, and metal support, Three components; 'blues': 74 x 231 in (188 x 586.7 cm); 'blood': 74 ¾ x 231 1/2 in (189.9 x 588 cm); 'bruise': 74 3/4 x 264 3/4 in (189.9 x 672.5 cm); overall approx. 74 3/4 x 797 1/2 in (189.9 x 2025.7 cm). © Glenn Ligon. Courtesy the artist, Hauser & Wirth, New York, Regen Projects, Los Angeles, Thomas Dane Gallery, London, and Chantal Crousel, Paris. Photo: Roberto Marossi (pages 146-147).

In 2018, Enwezor was putting together a series of talks for the Alain LeRoy Locke Lectures at Harvard University (Locke had been a leading figure in the Harlem Renaissance). Enwezor’s subject matter was not, however, limited to African American culture. Rather, he chose to focus on the intersection of black mourning and white nationalism in the US. Grief and Grievance focuses on the work of contemporary black American artists. The exhibition has been realised since Enwezor’s death with the curatorial support of Naomi Beckwith, Massimiliano Gioni, Glenn Ligon and Mark Nash. Gioni, the Edlis Neeson artistic director at the New Museum, says that Enwezor created a roadmap for the exhibition that the team of curators, artists and writers were able to follow: “We believe it is important to allow one of his last curatorial statements, one that speaks urgently to a nation in crisis, to be shared with the public … he had expressed his heartfelt wish that the exhibition should open just before the 2020 American presidential election, as a powerful response to an emergency in American democracy and as a clear indictment of Donald Trump’s racist politics. Enwezor saw Grief and Grievance as one of his most personal projects, and one of his most political. A Nigerian who had come to call New York home, he understood how the fissures in American society had deep historic roots and reflected generations of collective trauma.”

In his forceful introduction, Enwezor asserts: “The crystallisation of black grief in the face of a politically orchestrated white grievance represents the fulcrum of this exhibition. The exhibition is devoted to examining modes of representation in different mediums where artists have addressed the concept of mourning, commemoration and loss as a direct response to the national emergency of black grief. With the media’s normalisation of white nationalism, recent years have made clear that there is a new urgency to assess the role that artists, through works of art, have played to illuminate the searing contours of the American body politic."

Arthur Jafa, Love Is The Message, The Message Is Death, 2016. Video, sound, colour; 7:25 min. Courtesy the artist and Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels (pages 90-91).

Grief and Grievance presents the work of 37 artists working in a variety of mediums: video, painting, sculpture, installation, photography, sound pieces and performances made in the last decade, along with a number of key historical works and a series of new commissions created in response to the concept of the exhibition. There are video works from Theaster Gates, Kahlil Joseph and Arthur Jafa; paintings by Lorna Simpson, Adam Pendleton, Kerry James Marshall and Kara Walker; and installations from Rashid Johnson, Nari Ward and Hank Willis Thomas. Historic works by Jean-Michel Basquiat and Jack Whitten, among others, establish the context in which the most recent art has been made.

The publication Grief and Grievance establishes the context in which the variety of works can be presented and understood. There are essays by Enwezor himself, as well as by pre-eminent cultural commentators, including Nash, the journalist and essayist Ta-Nehisi Coates, the poet and playwright Claudia Rankine and the academic Saidiya Hartman. The essays are particularly affecting, as they seek to examine race in the US from historical, social, economic and political perspectives. Against recent events – culminating, two weeks before President-elect Joe Biden’s inauguration, in the storming of the US Capitol by individuals carrying Confederacy flags on 6 January – the accounts of historic events leading to the present attack on democracy, scholarship with passion, is illuminating. Grief and Grievance is a must-read for international audiences perplexed and horrified by what has reached fever pitch under Trump’s presidency. Art produced in this context provides experiential images to be examined and to enable the notions of loss, rage and injustice to impart the depths of despair and injustice that, for many, cannot be expressed in words.

The essay by philosopher Judith Butler, Between Grief and Grievance, a New Sense of Justice, is key to understanding the remit of the scholarly text that follows: “Grief and grievance: loss and the call to justice. How do they relate? Some gap opens between the experience of loss and the appeal to repair and rectify that loss, for there is no guarantee that justice can rectify or resolve a loss. And yet the energy within loss makes itself known as the cry, the appeal but also the grievance. It may be that the accident or the illness could not be averted, and that no appeal to justice makes sense. But industrial accidents and environmentally induced cancers are losses that could have been averted if governments and industries cared enough about the lives of the labourers and ordinary people. In those cases, loss is linked to the appeal to justice: it did not have to happen; steps were not taken to make sure that life was not lost. The loss is thus an injury, a deprivation, and the question of accountability becomes important. Grief leads to grievance, in the sense of a petition for justice, whether reparation, acknowledgement, or punishment, but when the law is the problem, to whom or what does one appeal?”

The immediacy and poignancy in abstracted visual forms adds to the scholarship and historical positions as context. Ligon quotes the poet and cultural theorist Fred Moten, who said in 2016: “I love all the beautiful stuff we’ve made under constraint, but I’m pretty sure I would love all the beautiful stuff we’d make out from under constraint better. But there’s no way to get to that, except through this.” The process of visualising the injustices and loss that have been perpetuated by the recent white supremacist movement is one way of expressing resistance, hope and survival. Grief and Grievance is a powerful and brilliant production, making it clear that art has a momentous role to play in overcoming loss and collective trauma.

In her essay Scale, Christina Sharpe quotes Whitten, who wrote in 2015 (A Circle of Blood, Sightlines (blog) Walker Art Centre): “The structuring of a viable worldview is hard work and filled with risk. Ultimately, we Americans must ask the most basic question: ‘What kind of world do we want?’ I know what I want. I want a world without the poisonous sickness of racism, without romantic fantasies of being black or white!”

The photograph Whitten uses in Birmingham (1964) is one of a series taken by the photojournalist Bill Hudson. It captures a young black man (identified as Walter Gadsden) being attacked by a police dog outside the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, on 3 May, 1963. The photograph is placed off-centre emerging from the predominant black paint, cardboard and aluminium foil that covers it in a visceral skin-like mesh. The artist explained that the “use of the stocking mesh over the photograph was straight out of WEB Du Bois’s The Souls of Black Folk, his notion of the Negro having been born with a veil that created a double-consciousness (‘this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity’).”

Foil is used to represent skin that has been savagely torn; it creates an image of a wound that explodes outwards from the picture plane, hitting the viewer with a newspaper image of the young black man with a dog tearing the sweater where his arm had been. In Birmingham, Whitten uses materials that evoke the physicality of violence and pain, and they are presented to convey the searing truth of the racism of the 1960s. Presenting it again, in the 2021 exhibition, reinforces that freedom must be fought for, constantly reasserted, in every generation. In The Architecture of Hope (2015), Charles Jencks described hope, as a chain that always needs mending, citing Viktor Frankl’s book Man’s Search for Meaning, based on Frankl’s experiences as a prisoner in a Nazi concentration camp.

Nari Ward, Peace Keeper, 1995. Hearse, grease, mufflers, and feathers, 144 x 116 x 264 in (365.8 x 294.6 x 670.6 cm). Installation views: Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, 1995. Courtesy the artist, Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, and Seoul, and Galleria Continua, San Gimignano, Beijing, Les Moulins, and Havana (page 234).

Nari Ward’s installation Peace Keeper (1995) is consistent with his practice addressing memorialisation and time. Sharpe says: “Ward uses familiar materials toward a process of defamiliarisation. We are familiar with the hearse as a signifier of mourning and death: it is the means by which the body of the deceased is moved. The hearse is not death, for death happens before the hearse arrives: the hearse is about movement. But the hearse here is inert – it has bars around it that block its ability to move. The hearse is burnt out, covered in tar. Parts are suspended, dripping from the ceiling. Its multiplied innards – exhaust pipes with their silencing mufflers – seem to have exploded out of it. They sit gathered around the hearse like so many bodies, like so many bones. We enter into a state of incomplete, unfinished mourning. Mourning itself is under siege.”

Grief and Grievance is a profound and urgent exploration of the manner in which artists have confronted issues of race and grief in modern America. It gives voice to artists grappling with concepts of mourning, commemoration and loss in the context of their engagement with the social movements, from civil rights to Black Lives Matter. A brilliant, essential read.

• Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America, ‘originally conceived by’ Okwui Enwezor, curatorial advisers: Naomi Beckwith, Massimiliano Gioni, Glenn Ligon, and Mark Nash, is published by Phaidon/New Museum, New York, price $80.

An exhibition of the same name, originally conceived by Okwui Enwezor, will be held at the New Museum, New York, from 17 February to 6 June 2021.