Garth Evans. Untitled No 38, 1967-68. Fibreglass, four units 183 x 61 x 61cm. Image courtesy the artist.

Chapter Gallery, Cardiff

14 September 2019 – 26 January 2020

by SAM CORNISH

Two distinct types of space provide the setting for the sculptures in Garth Evans’s exhibition at Chapter Gallery, Cardiff. The first are the cubic volumes of the irregularly laid-out galleries that lead off to the right from the space immediately beyond the entrance. The second, strikingly different, is formed across the surface of the large plinth-table that occupies almost all of the single gallery to the left. The galleries leading off to the right include sculptures and wall-reliefs from 1960 to 2010. On the plinth-table to the left are a group of around 15 slightly larger than hand-sized painted bronzes, made between 2007 and 2017, which Evans calls collectively Little Dancers.

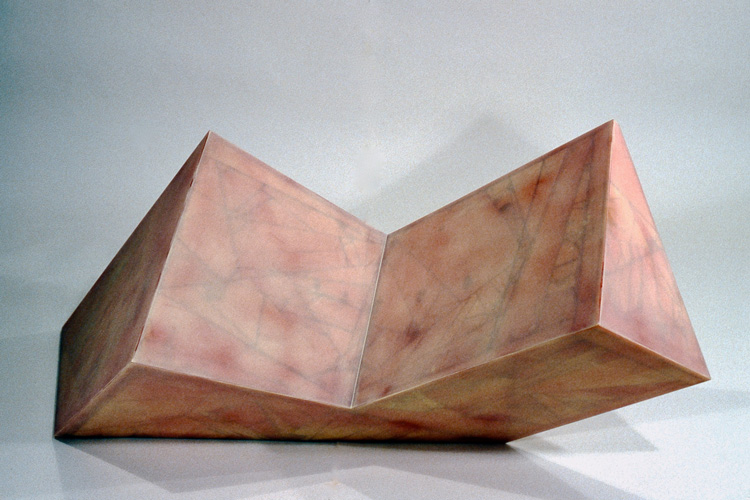

Garth Evans. Bodies Hold, 1992-94. Fibreglass over cardboard, 58 x 133 x 91 cm. Image courtesy the artist.

In the spaces to the right, individual sculptures are positioned deftly on either wall or floor. The sculptures vary in size, but they all share a natural and unforced sense of scale. Nothing feels too big or too small – each work appears to be at 1:1. This seems quite a feat, given the perceptual tricks and ambiguities Evans’s work involves. There is a partial exception for Untitled No 38, a large orange sculpture from 1967-68, squeezed into the final gallery, although even this is by no means positioned to overawe the viewer. But otherwise these are generally sculptures that appreciate the space they have been provided with, comfortably taking their place within it, without seeking to dominate or monopolise their surroundings. Perhaps his eschewal of the grand statement, certainly in his works from the late-70s onward, partly explains why Evans is not better known. I would guess you would probably learn more from a foot-high sculpture by Evans than the whole spread of the extravaganza that sculptor-impresario Antony Gormley is about to present to the public at the Royal Academy. Or perhaps the difference is that Evans would offer a more authentic experience of sculpture, as he is by no means a didactic artist.

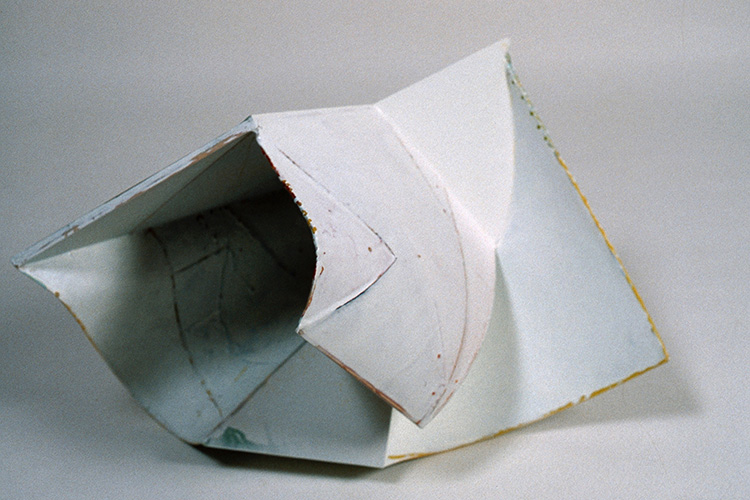

Garth Evans. Lost Hope, 1990. Epoxy resin, foamcore, paper, paint, 51 x 86 x 64 cm. Image courtesy the artist.

In many ways, the work seems easy to like, although, in general, without being too puritanical about it, Evans does not offer the viewer overt drama. Rather than letting his sculptures speak loudly or punch above their weight, he would prefer them to draw the viewer in. Even the most immediately appealing of them has a somewhat knotty core, although this does not mean they have a readily identifiable centre. They are not easy to know, and I sensed that many of the works would reward repeated visits, or even better, should be lived with, so they could give up their secrets at their own pace. Colour, after the 60s always distinctly textured, and often located under layers of clear resin, has a similarly inwardly focused orientation, in holding the sculptures together like a skin more than it allows them to call across space.

Garth Evans. Mrs Turpin’s Pig, 1987. Epoxy resin, foamcore, paper, paint, 51 x 117 x 48 cm. Image courtesy the artist.

There is a neat concordance between the slightly higgledy-piggledy sequence of the galleries to the right and the sculptures they contain. Both unfold in modestly unexpected ways, although the sculptures in much less linear fashion. Within these galleries, the works talk to each other or create a flow from one space to the next. All the sculptures have an undeniable and intimate relationship with either wall or floor. The floor-based works are in constant communication with the ground, while those existing on the wall – “hung”, although literally true, is far too mono-directional – have a similar sense of remaining in touch with the plane against which they are encountered. These close connections to either wall or floor leave the middle of the galleries surprisingly empty, despite the large number of works shown. It is worth noting that this central space, untethered from wall or floor, that on this showing at least Evans avoids, is the territory that a sculptor such as Anthony Caro most frequently operated in. I think the same could be said of Richard Deacon, whose work exists somewhere between Caro’s and Evans’s in this and other ways.

Evans himself says that his sculpture has always been basically figurative and, looking at this exhibition, it would be hard to disagree. Yet this needs to be qualified by saying that his sculpture is not about the upright figure, whose structure and image has been in so many ways central to the history of the discipline. More relevant is what other commentators have already identified as the “creaturely” aspects of Evans’s sculpture. Although he is careful to avoid pushing the point too far, these works could almost be seen as strange beings. But if they are beings, they are just as much objects. They combine the animation of the living thing with the inertness of the object, sometimes natural – a pebble say, and Henry Moore and Hans Arp are both relevant here – but more often a manmade thing, a pot or a piece of furniture. These observations apply as much to the planar works as to the biomorphic. Here it is misleading to strictly divide planar and biomorphic from each other. Each mode contains a large dose of its seeming opposite. This is not as true of the group of ceramic works from 1998 and 2013 in the penultimate gallery, which I find the least satisfying works in the exhibition.

-2nd-View-copy.jpg)

Garth Evans. Hollow Form No. 28, 2004–13. Ceramic, 44.5 x 61 x 35.5 cm. Image courtesy the artist.

I said that the sculptures and the galleries both “unfold”. It would be more accurate to say that the sculptures close back in on themselves as much as they open outwards. Most contain two or more elements that meet each other a little like parts of the body. But if bodily movement is figured, it is of an awkward or abbreviated or introverted kind, a spiky crossing of legs or a defensive folding of arms. We are not dealing with the easy fluidity that moves through a ballet dancer, fingertip to fingertip, head to toe, but something more like the uncomfortable bracing of elbow joint against shoulder, as the finger-tips search for an itch on the back that is only just in reach. These distant echoes of the body’s parts and junctions are always contained within more abstract structures. In some of the wall-pieces this evocation of the body is ambiguously overlaid with a curious resemblance to heads or faces. Are they turned away or blankly facing us? I can imagine a novelist describing a face as having a cross-legged expression (or eyes like folded arms) and Evans seems to be doing something similar here, or at least has uncovered the possibility. The unlikeliness of this is part of their hard to define, but undeniable humour.

The large group of Little Dancers on the table-plinth are creaturely in fairly straightforward fashion, shape-shifting aliens caught in an implicitly endless process of transformation. They have a relaxed, almost casual, fluidity. This marks them out from much of the rest of the exhibition, although the Dancers are not without their own tautness and precision. Their openness means they are the least object-like of all the work on display. They recall the movements of fingers or limbs, but also have an architectural dimension, a fantasy architecture of floors, beams and struts caught in a state of flux. The large surface of the plinth-table transports the Little Dancers into an entirely different realm to the rest of the exhibition. The works elsewhere have a direct relationship to one another, a sense that they all share a space, and that we share it with them. Here though, the surface is large enough to cut off the Little Dancers from their surroundings, creating their own realm, full of strange perspectival illusions, like people dispersed along a beach or the biomorphs in a Yves Tanguy landscape. These illusions draw us in and give the sculptures a monumental quality. Avoiding monumentality in all but the smallest works in the exhibition seems a form of quiet contrariness very much in the spirit of Evans’s sculpture.