Tselinny Center of Contemporary Culture, 2025. Copyright Laurian Ghinitoiu and Asif Khan Studio.

by VERONICA SIMPSON

Asif Khan tends to the poetic – and who can blame this young British architect for waxing lyrical on opening his first permanent public, cultural building. It has taken 15 years of realising mainly temporary, albeit widely admired, national pavilions at assorted Expos, Olympics and even a Summer Serpentine pavilion, and the early promise of being shortlisted for the Helsinki Guggenheim competition in 2015. But the porous and welcoming Tselinny Center of Contemporary Culture in Almaty will undoubtedly be a boost for his and Kazakhstan’s profile on the global contemporary art map.

At the official opening of the centre this, Khan’s speech was laced with references to Kazakh mythology – specifically the spirits of the sky (Tengri) and the Earth (Umai) – which he sees translated into the roof and the floor of this imposing building, united via a “cloud”, an undulating screen of thin, white fins that line the entrance facade. He says: “The power of the cloud is to soften the building. It’s a device that we have to walk through – this thing of confusion, of unknowable form, within this rigid frame. And when we do this, we are set in a new state of mind: we are ready to experience art in a different way.”

_Unkown.jpg)

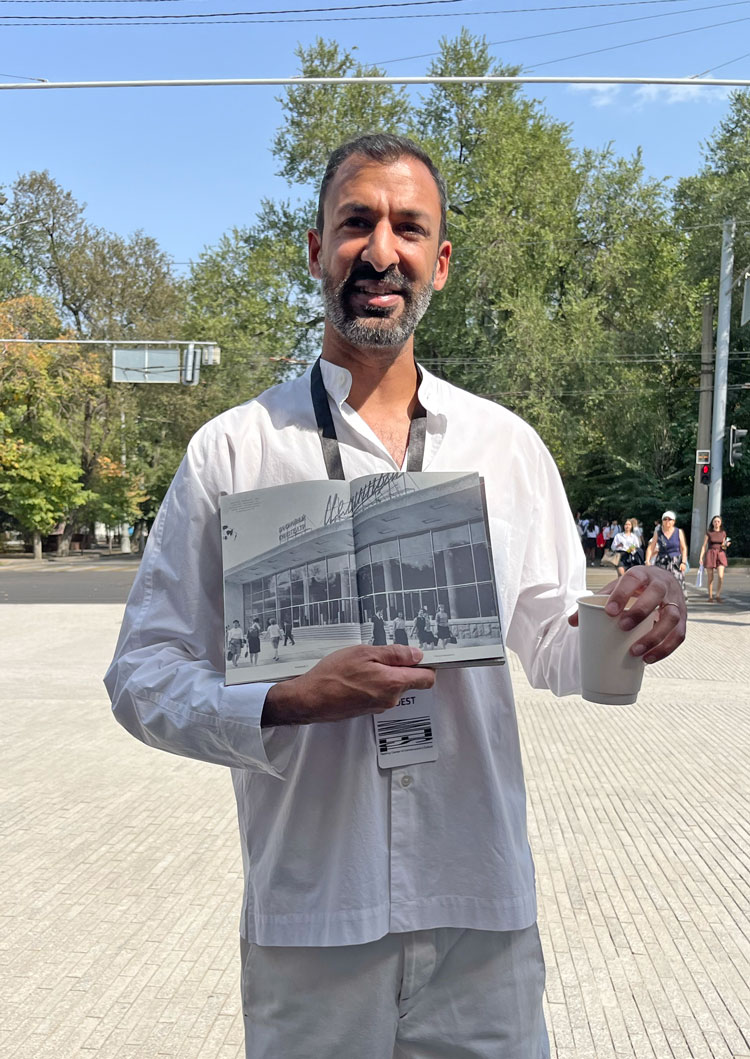

Tselinny Center historic photograph from the 1960s. Photographer unknown.

This need to reinvent the building, as well as reframe the experience of what is inside it, was very necessary. Tselinny was first a large Soviet cinema, built in 1964, to screen state-approved films. Khan says: “The cinema was built on the 10th anniversary of [Soviet leader Nikita] Khrushchev’s Tselina campaign [Tselina roughly translates as “virgin lands”], the campaign to transform sacred nomadic homelands – the Steppe of the Kazak people – into agricultural land … And that moment in time had a dramatic effect on the Kazakhstan we live in today. It was the nail in the coffin of a form of life that had endured for thousands of years beforehand, nomadic life. So, the name represents something that is quite a catastrophe in these lands. A cinema can have wonderful memories but also be a place where propaganda is shown. Like a lot of things in Kazakhstan, it can have positivity and negativity. This project and the reconstruction is very much about dealing with those past histories.”

_Asif_Khan_Studio_2025.jpg)

Tselinny Center exterior, 2017. Photo © Asif Khan Studio 2025.

If Khan sounds proprietorial, it is with good reason. He has invested considerable time and energy in getting to know this region, first in designing the UK’s pavilion for the Astana Expo in 2017 and, subsequently, exploring its vast and varied landscape with his Kazakh-born wife Zaure Aitayeva. The pair met during the Expo, where she was the chief architect, and her involvement has been integral to the Tselinny’s realisation; Khan credits her as lead architect.

The Astana Expo, in fact, planted the seeds for this new scheme. Tselinny’s director, Jamila Nurkalieva, then newly returned to Kazakhstan after working in arts management in Paris, was invited to programme contemporary art explorations and discussions for the duration of the Expo. She recruited a fellow returned Kazakh national, Alima Kairat (alumnus of the Courtauld and Goldsmiths, University of London and now Tselinny’s artistic director) as one of the curators. Khan was invited to speak at a symposium hosted by Nurkalieva, and says: “What I loved about this experience was the atmosphere of common ground there … People from all walks of life were interested in everything to do with the future of Kazakhstan and its culture. I had never been in a discussion like that. [In the UK,] ordinary people are afraid to speak. Discussions around culture and architecture tend to be dominated by professionals. But here it was a free exchange of ideas. So, I thought: ‘Whatever Jamila does in the future, I want to be part of it.’”

Tselinny Center of Contemporary Culture, 2025. Copyright Laurian Ghinitoiu and Asif Khan Studio.

At about that time, Kairat’s father, oil and gas magnate and sports entrepreneur Kairat Boranbayev, had just acquired Tselinny from the person who had been running it as a nightclub and restaurant since Kazakhstan gained independence from the USSR, in 1991. [Boranbayev, it should be noted, was sentenced in 2023 to serve eight years in prison for embezzlement and money laundering, but had his sentence reduced on appeal, after handing over a chunk of his assets, according to a report in The Art Newspaper, April 2025; in the same report, Nurkalieva insisted that all such matters had been settled]. Boranbayev offered Tselinny as a potential site (he is a founder, investor and director, but claims no role or influence over the programme).

Asif Khan stands in front of the new facade showing picture of original cinema frontage. Photo: Veronica Simpson.

The big practical issue at the time was how to proceed, when the prevailing advice was to knock down the building? The interiors had been significantly deconstructed during its nightclub era, and the original was not built to withstand the earthquakes that are a regular occurrence in the region. However, the team felt an emotional pull from this building – the symbolism of what it had been, and how its transformation could be pivotal in harnessing a new energy – as well as the environmental considerations. It took two years to find the engineering expertise to achieve their aims while delivering on their ambitions.

The Tselinny Center retains the scale, frame and name of the original. Khan says: “We reinforced the auditorium with a steel frame internally. We kept the original roof – the exact same roof, but with reinforcement. The horseshoe shape which is around the auditorium was all rebuilt, but within the original footprint of the building. This building lives in the collective memory of so many people in Almaty, we didn’t want to change its size, its familiarity for so many people walking past. It mediates so carefully between the height of the surrounding buildings. Any alteration to this would have upset that balance and changed the continuum that we were picking up on.”

Tselinny Center of Contemporary Culture, 2025. Copyright Laurian Ghinitoiu and Asif Khan Studio.

So much else has changed, however. Where the original had to be entered via a series of steps, the new Tselinny is accessible and flexible throughout. The ground floor has been dug out to the point where it can all be on one level, including the paving outside. Activities and apertures have been placed on every facade, to give it strong street-level animation, while connections within and around the building maximise potential for adaption and accommodation for a multitude of uses. “All spaces are interconnected,” says Khan. “Some of them with several doors between them. They connect with the boulevard, to the rest of the city. From the auditorium, you can enter straight into the park. Or out to the north side of the building, that has yet to be designated. So, a future exhibition or programme could be chaining many of these spaces together – the park, the south terrace.”

Looking on to that south terrace is the Tselinny’s restaurant/cafe. A light-filled, substantially glazed space. The terrace’s landscaping, in form and materials, echoes the glacial rocks and rivers of the region. As with all aspects of the project, says Khan: “My approach was to go back in time and look into deep history and find what lies beneath the hidden stories, and one of the ways I did that was to acknowledge that Almaty is an enormous riverbed. Glacial water from the surrounding mountains comes down into this valley. Anywhere you dig foundations in the city, you find these glacial stones. You’ll also find burial mounds, coins from the 7th and 8th century. There’s a lot here that you wouldn’t know about from the Imperial grid city that’s above it.” He gestures to the stones arranged around the terrace. “These are the same stones you see in the landscape.” In fact, many of the smaller stones used in this terrace were retrieved from the basement’s excavations.

Tselinny Center of Contemporary Culture south facade and terrace with floating concrete panels showing Asif Khan's interpretation of Sudorkin murals. Photo: Veronica Simpson.

As he shows us around the building’s exterior, he points to the flowing pathways that have been designed into the granite tile paving, mirroring the contours of local riverbeds. “We want to encourage people to follow these paths and connect to the spirit of fluidity and movement that’s been forgotten,” he says. Along the north elevation, the more functional side, there are workshops, staff entrances and a loading bay. Here, Khan has continued his watery analogies, with doors of stainless steel, “to get the partial reflections of ourselves”. This, too, can be animated for exhibitions or events. “The loading bay we envisage as a potential, hidden venue for the institute. It’s a zone where off-piste or undercover projects can happen. It goes down into a massive storage area.” A large basement occupies the entire building’s footprint, providing storage and accommodating two big kitchens that can facilitate major events, as well as supply the cafe’s daily needs.

Steel doors along north side of the Tselinny Center of Contemporary Culture. Photo: Veronica Simpson.

There are several mature trees on the site, and further planting of local species (aspen, elm) is scheduled to boost the surrounding tree canopy. At present, there is no route or animation around the western edge of the building, just a tall fence above which you can see the minty green walls and golden domes of St Nicholas Cathedral, a Russian orthodox gem left over from Imperial Russian times, which the Tselinny was strategically placed to obscure from public view: it was set directly in front of it, at the far end of Kabanbay Batyr Street, one of the city’s most prominent, tree-lined boulevards. Khan assures us the barrier will come down, and a tearoom will open along the rear of Tselinny, serving visitors to the cathedral as well as the local park.

Tselinny Center of Contemporary Culture, 2025. Copyright Laurian Ghinitoiu and Asif Khan Studio.

As for the entrance, beyond that dramatic curtain of fins, full-height glazing – precision engineered in China – reveals a spacious, column-free foyer, which features a shop and exhibition/circulation and event space. There is a smaller exhibition space beyond, and a “capsule” gallery to one side, but beyond these, at the heart of the building, where the cinemas used to be is one massive auditorium, 35 metres by 35m with an 18-metre-high ceiling. Khan says: “It’s the original volume of the cinema.”

Barsakelmes performance, 6-7 September 2025, Tselinny Center of Contemporary Culture. Copyright Laurian Ghinitoiu and Asif Khan Studio.

Its full height currently hosts a vivid, felted sculptural installation by the artist Gulnur Mukazhanova, which is part of the opening performance – Barsakelmes. This is a collaborative work evolved over several months with a large team of Kazakh artists, musicians and poets, drawing on stories from the past, evoking ancient spirits, and culminating in a noisy and exhilarating ceremony of rebirth and renewal, complete with shamanic chanting.

The idea for this flexible hall is that it can host major theatrical events or have multi-level structures inserted into it for more orthodox exhibition display. There are ateliers and workshops on the floor above and a rooftop restaurant that will re-open views across the city between the boulevard, the park and the Cathedral.

You can recognise the language of many of Khan’s earlier structures: the flowing fins similar to his Serpentine summer pavilion (2016) and that sense of entering via a curtain or cloud not dissimilar to the proposed Guggenheim Helsinki (though in that case, the fabric-like drapes over its square form were to evoke a tablecloth). There are many ways in which this project reflects his affinity with waterways, evidenced in his 2024 snaking red pedestrian bridge for Canada Water. All these elements and references from across his practice are displayed in an exhibition reflecting on his practice, shown here under glass on a large, circular table in the Tselinny’s foyer. This white table is a permanent fixture, and will feature in storytelling displays, feasts and gatherings.

.jpg)

Tselinny Center of Contemporary Culture, 2025. Copyright Laurian Ghinitoiu and Asif Khan Studio.

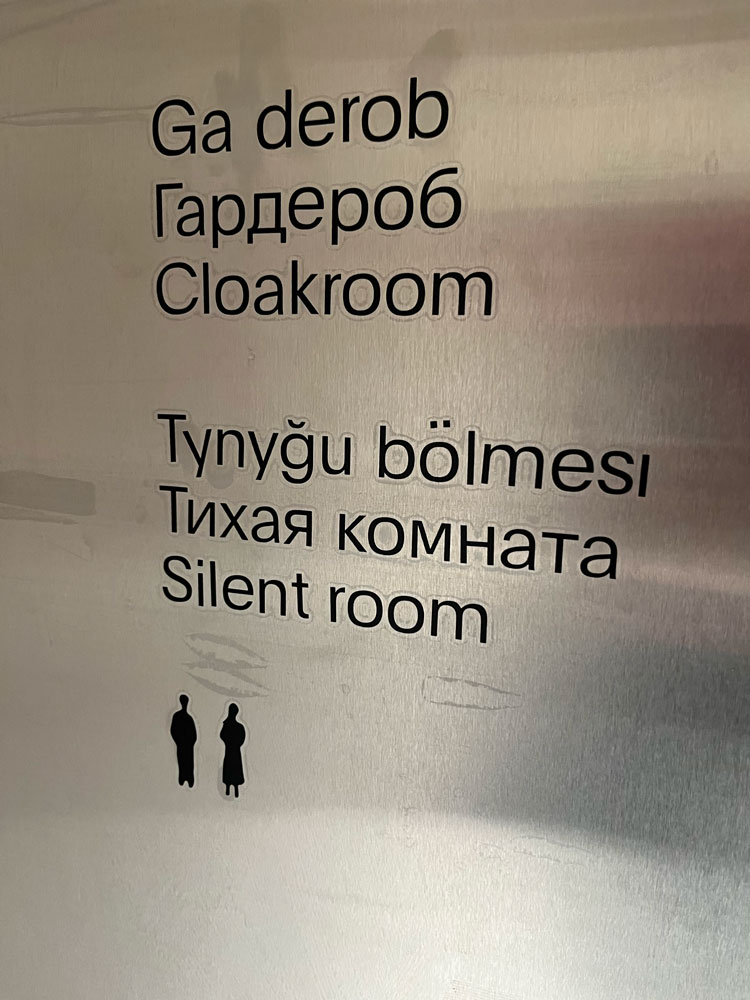

It is just one of so many elements of care and craftsmanship, and informal invitations to inhabit the area within and around the building (there is also a silent room for prayer or meditation; a reminder, perhaps, that the Kazakh population is predominantly Muslim). One of the major components to be salvaged and re-presented was a dramatic, 42-metre-long sgraffito by the Russian-born, Almaty-adoptee Evgeny Sidorkin (1930-82), which lined the original cinema foyer. Thought to have been destroyed or lost in the nightclub refurb, large panels of it were rediscovered in 2018, stashed behind the nightclub’s office partitions. Although damaged, they have been cleaned up, their missing portions filled in with pristine white plaster (in a nod, says Khan, to the Japanese art of kintsugi, gilding over the cracks or damaged elements of precious vessels). The recovered panels are placed where the sgraffito was before, along the foyer’s interior wall.

Tselinny Center of Contemporary Culture, 2025. Copyright Laurian Ghinitoiu and Asif Khan Studio.

In another nod to its interim incarnation – and the inaccurate, reworked version of the Sidorkin sgraffito which was presented along the nightclub’s exterior wall – a free-floating concrete panel wall along the south elevation has been perforated with mysterious incisions, which Khan describes as “a kind of cloudscape of symbols”, inspired by the original and the later copy. He says: “The materials we are using are memories of the original building’s materials, whether concrete, as used in these panels, or this particular tone (of steely grey on the rear of the building), to match the original. These new concrete panels, which match the texture of the original, have these symbols (which) I drew from the white space from the copy. These are fragments of the memory of the memory. Why did I do that? There was a connection to a past that we can’t access any more. But symbolic languages and mythologies can connect us to that time. These are fragments of a language that we can sense is familiar. It’s a busy route here, kids go to school here, old ladies go shopping. They will remember these, but now we’ve reinterpreted it. If you go around the Almaty region, there are lots of sites with petroglyphs. Actually, the whole of Kazakhstan is full of petroglyphs, geological markings in stone; these fall into that category of information that we’re trying to decipher. It is information and possibility.”

Wayfinding and logos designed by Asif Khan. Photo: Veronica Simpson.

A decision was taken to keep the exterior clear of signage, unlike the original, which broadcast Tselinny across the top in enormous neon Cyrillic letters. “We didn’t put a sign on the top. It doesn’t need to be shouted out what it is. We did all the wayfinding and pictograms ourselves because we wanted to control what the place means and how it spoke to the people at every level.”

And what of the programme inside the building? During its seven years of evolution, the Tselinny operated as an off-site entity, run by Nurkalieva and Kairat, working with artists, activists and local enthusiasts and encouraging conversations around what kind of space and place these creatives felt was needed. There were apparently 350 workshops, including an exhibition in the stripped- out Tselinny, revealing the work in progress as well as the proposals to the local populace. Nurkalieva says: “We had many conversations, discussions, schools, summer schools. When we set up a temporary gallery space not far from here, which we rented from the state museum, we said to young artists they could apply to have a solo show there, develop their own curatorial initiatives. And there was another grant for young artists, who could apply to realise a full-scale project, with researchers, with scenography.” The Barsakelmes opening show was workshopped in a similar manner. The collaborative approach seems now to be baked into their DNA – reflected in a decision not to hire a curatorial director. Nurkalieva says: “We were just intuitively thinking we need to try it this way. We have worked with curators before who came to us and said I want to run this. And we thought: ‘No, thanks.’ It can’t be just one person’s opinion. We took a long time developing our ideas, developing an amazing team.

Tselinny Center of Contemporary Culture, 2025. Copyright Laurian Ghinitoiu and Asif Khan Studio.

“Tselinny is the space of the thinker. It’s very important that it becomes a centre of connection, of interrogation. Our centre is open for dialogue. We don’t have only one concept or one history. We are an open, collective institution so we can discuss our agenda together … We want to build a bridge between academics and artists and curators, to build a shared terminology and be able to exchange on the same ground (to create) an independent, sustainable platform for the community.”

Tselinny Center of Contemporary Culture, 2025. Copyright Laurian Ghinitoiu and Asif Khan Studio.

How the art it presents will be received is another matter. After freeing itself from nearly two centuries of either Imperial Russian or Soviet rule, this oil- and mineral-rich country has prospered. But the spirit of authoritarianism prevails, with violent protests erupting – and being viciously suppressed – in 2022. We were told, by one well-informed local, that these riots were in protest at the continuing influence and interference of its first president, Nursultan Nazarbayev, who oversaw the transition to independence in 1991 but then retained power for 29 years, before appointing his successor. However, reports indicate that privately funded institutions are far freer from interference than government-run ones. This would seem to be borne out by the fact that yet another, privately funded modern art institute opened, just days after Tselinny – the sprawling Almaty Museum of Arts. Owned by motoring and oil magnate Nurlan Smagulov, and boasting his own, somewhat patchy collection of modern and contemporary Kazakh art. In a building I would describe as “Guggenheim Lite”, designed by UK architects Chapman Taylor, it offers 1,000 sq metres of exhibition space, and includes permanent works by Richard Serra (a large, walk-through corten steel sculpture – also very Guggenheim), a Fernand Leger ceramic mural, and outdoor sculptures by Alicja Kwade and Yinka Shonibare. The artistic director is Meruyert Kaliyeva (educated in art history at University College London and Christie’s trained), who is also the owner of Almaty’s only commercial art gallery. My impression is that this museum is all about spectacle, and monetising the owner’s collection and the value of the artists within it. If so, it is a very different animal to the Tselinny. However, the attention and momentum these two new contemporary cultural centres bring to this historic city are bound to have interesting consequences for the creative community at large.

• https://www.tselinny.org/en