Mequitta Ahuja, Notation, 2017 (detail). Oil on canvas, 213.4 x 182.9 cm. Courtesy the artist and Tiwani Contemporary.

Whitechapel Gallery, London

24 February – 5 June 2022

by JOE LLOYD

Rodney Graham stands in the centre of a tasteful mid-20th-century villa, hair perfectly coiffed and pyjamas luxuriantly silky. Handsome catalogues sit piled around the sofa and jostle with antiques for prominence on the table. Graham has laid down a neat carpet of newspapers, whose stories on labour struggles, the cold war and the stock market sit ignored. He pours bowls of paint down a sloping canvas, creating a tasteful – that word again – abstract pour painting.

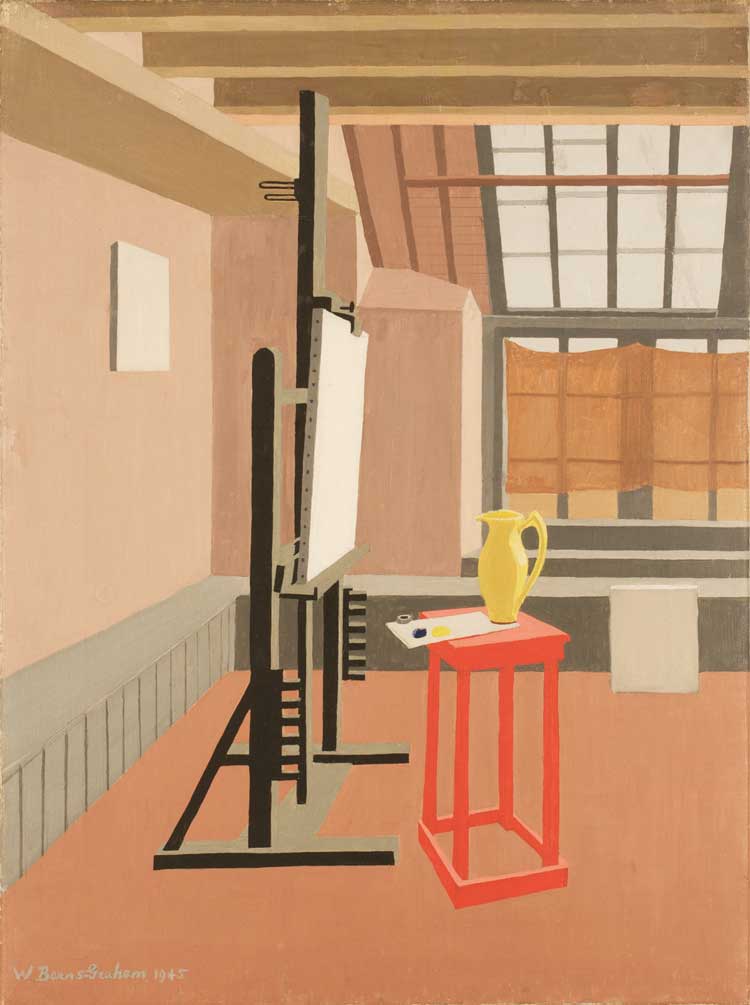

This huge three-panel photograph, The Gifted Amateur, Nov 10th, 1962 (2007) presents what Graham calls “the playboy mansion of studios”. For this fictitious dilettante, painting is a pleasurable hobby, and the studio is just a careful redressing of his home. Real studios are seldom so neat. Giacometti painted his portraits in a drab room whose bare walls were covered in marks, stains and doodles. Francis Bacon worked amid giant colourful daubs of paint, like a field of flowers. The floor of Jackson Pollock’s studio is covered in errant drips from his massive inky canvases. And Helen Frankenthaler’s paintings served as floors and walls in hers.

Wilhelmina Barns-Graham, Studio Interior (Red Stool, Studio), 1945. Oil on canvas, 65 x 45.6cm. Wilhelmina Barns-Graham Trust © Wilhelmina Barns-Graham Trust.

Bruce Bernard’s 1983 photograph of Lucian Freud shows him tumbling on his studio floor, next to piles of rags and yet more splats of paint. Years later, Darren Almond’s The Remnants (Freud) (2021) depicts the deceased artist’s paint-soaked rags as objects part-sanctified, part-filthy. In his earlier video work A Real Time Piece (1996), Almond presented a live broadcast from his own meagre studio, which has all the allure of a dilapidated office awaiting demolition. It is often empty.

All of these and more feature in A Century of the Artist’s Studio: 1920-2020 at Whitechapel Gallery, a genuinely ambitious exhibition. It collects artworks, photographs and objects that reveal, depict or evoke the studio, tracing its numerous transformations through a century in which the cult of the artist grew like never before. The Whitechapel’s galleries have been transformed into a labyrinth of smaller chambers, many of which feature recreations of famous studio spaces. It is a fantastic capstone for the outgoing director, Iwona Blazwick, who, over two decades, turned the Whitechapel into the many-pronged institution it is today.

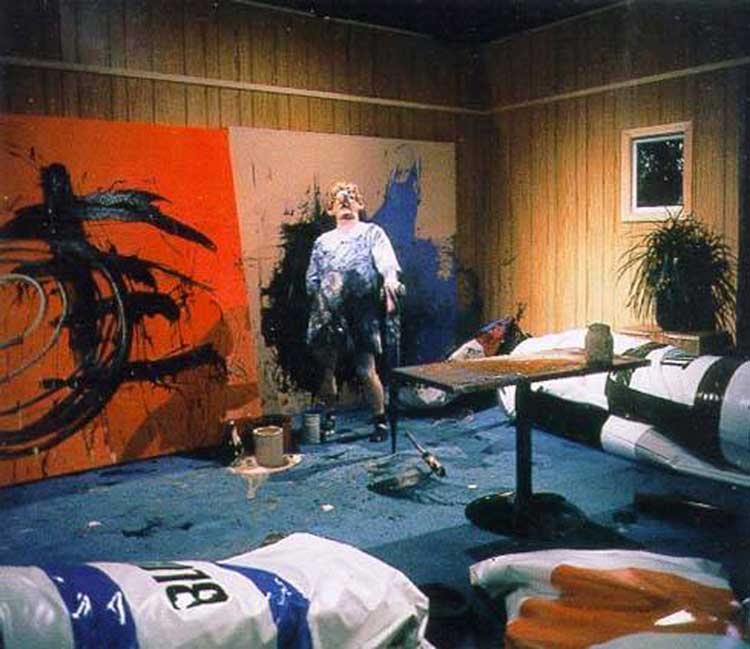

Paul McCarthy Painter, 1996. Video, colour, sound 50:01 mins © Paul McCarthy.

Writers endlessly write novels about writers. Film-makers have always loved making films about film-making. Artists have not always been so keen to share. In the Renaissance, the studio was a workplace, too lowly to be worth depicting. Things began to shift in the 17th century. Rembrandt painted himself in his studio. The impressionists dabbled: both Manet and Monet painted the latter’s waterborne atelier. But it took until the modern age for the depictions of the studio to become more commonplace, as seen with Matisse and Bonnard’s renderings of their homes.

Parallel to this, the invention and expansion of photographic printing allowed images of the artist in their studio to circulate. The Whitechapel has assembled an extraordinary collection of photographs. These minutely capture the changes in the way artists’ workplaces were presented. Henri Cartier-Bresson meets the venerable Matisse in 1944, in his textile-covered bedroom. It feels as if we have intruded, only partially welcome, on his private sanctum. Picasso was very different. A 1963 picture taken by Robert Doisneau, by contrast, shows the aged master clad in a flowing orange slip, part monk and part showman, presenting his work with a flourish. And in 1974, Leonardo Bezzola depicted Jean Tinguely as a brooding supervillain crouched amid his terrifying automatons. The studio becomes a place in which to perform.

Francesca Woodman, Untitled, New York, 1979. Estate digital c-print, 20.3 x 25.4 cm. Courtesy The Woodman Family Foundation and Victoria Miro. © Woodman Family Foundation/DACS, London 2021.

Some studios remain primarily workshops, strewn with tools, materials, unfinished work and assorted mess. Dieter Roth’s table is covered in suspicious marks. Hassan Sharif’s atelier features all sorts of objects left unused at his death, including wooden spatulas, a bucket of springs and numerous brightly covered flip-flops. The elements from both these studios have been moved into Whitechapel, turned into artworks once their users are no more.

Sometimes artists consciously turn their studios into artworks. There is a recreation of the fireplace at Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant’s masterpiece of neo-Renaissance kitsch, Charleston in Sussex, which served as house, holiday home and studio to a range of Bloomsbury associates. Nearby is a replica fragment of Kurt Schwitters’ lost Merzbau, a sort of dadaist grotto adorned with a magpie’s collection of keepsakes. It has the spiky protrusions of German expressionist cinema. The Polish artist Edward Krasiński lived and worked in an apartment in which a single blue line ran across the walls and through all his works.

The idea of a workplace of one’s own can be liberating, whether politically or creatively. Three photographs document Tracey Emin’s 1996 performance piece Exorcism of the Last Painting I Ever Made. Emin locked herself in a makeshift studio for two weeks and forced herself to paint and paint. In the process, she developed the style for which she would become famous. Emin, naked, could be glimpsed through lenses in the walls: a radical exposure of her artistic process. I was not familiar with the extraordinary arpilleras, embroideries from Chile, in which anonymous women from shanty towns created critiques of the Pinochet regime on burlap sacks, promoting their travails to the world.

Martha Rosler, Semiotics of the Kitchen, 1975. Film, black-and-white, sound, 6:09 mins. Courtesy of Martha Rosler and Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI), New York.

Conceptual art radically changed the nature of the studio, which, in effect, becomes anywhere the artist creates work. In Martha Rosler’s film Semiotics of the Kitchen (1975), the artist holds up kitchen objects one by one, intoning their names in a deadpan voice, then demonstrating them with the fury of a murderer plunging a knife into a victim. For women denied creative agency of their own, the kitchen becomes a surrogate studio. Some artists dispensed entirely with the idea of the studio as a fixed interior space. The 1970s collective Laboratoire Agit’Art performed on the streets of Dakar, turning the city itself into a living atelier. And Carolee Schneemann regularly used her own body as a canvas: does this make the air around her a sort of intangible studio?

Wolfgang Tillmans after party (c) 2002, Inkjet print, 138 x 208 cm. © Wolfgang Tillmans, Courtesy of Maureen Paley, London.

The Whitechapel segregates the exhibition into thoughtful sections. But this is a show that lets you take your time, loop back and make your own connections. If it tells a single chronological narrative, it is one in which the studio gradually expands to become a subject of art in its own right. Wolfgang Tillmans’ After Party (c) (2002) sees the German photographer present his studio scattered with beer bottles on the morning after; the studio is now a place for gathering and celebration. Yet some mystique always remains. Louise Bourgeois’ Cell IX (1999) casts the studio as a prison. Three disembodied pink marble hands touch atop a giant slab, looked over by three mirrors. Entrapped, observed and mutilated – this studio is not a great place to be. But I would love to see the work these delicate hands create within it.

Louise Bourgeois, Cell IX, 1999. Steel, marble, glass, mirrors, 213.4 x 254 x 132.1 cm. Courtesy D.Daskalopoulos Collection. © The Easton Foundation/VAGA at ARS, NY and DACS, London 2021.