Chronus Art Center, Shanghai, and Rhizome at the New Museum, New York

30 March onwards

by HARRIET THORPE

As museums and galleries closed up during lockdown, a flurry of “viewing rooms” opened – showing artwork mainly made for another dimension, the physical one. The Chronus Art Center and Rhizome responded to lockdown with an open call to the international media art community. For them, it was an opportunity to reflect critically on the medium of the internet itself, and to push the boundaries of the online world – net art’s natural habitat.

The curator is Zhang Ga, of the Chronus Art Center, who has more than a few net art credentials, including his role as professor of media art at Tsinghua University in Beijing. He says: “It is one thing to put a picture online and totally something else to show network-specific art, which we often call net art. It had its very vibrant, productive and also controversial days in the 90s when the internet was a volatile space, artists were out there inventing their own browsers (Maciej Wisniewski’s netomatheque) and trying to disrupt corporate monopolies by creating alternative infrastructures (Paul Garrin’s Name.Space).”

As screen times soared across the world during the Covid-19 pandemic, Ga selected 10 works that expressed the importance, benefits, problems and politics of the internet. “When you are isolated while observing social-distancing mandates and many people are already telecommuting and working from home, the network becomes so visibly essential and indispensable. Not to say that the network wasn’t the foundation of contemporary life before, but it has become such a ubiquitous given, like what Heidegger called Zuhandenheit (readiness-to-hand) and was forgettable until normal routines went kaput and then it became Vorhandenheit (presence-at-hand),” he says.

Evan Roth. n22.230210e113.940187.hk, 2017. Infrared video.

In the exhibition, artist Evan Roth brings these seemingly invisible internet networks to the surface in n22.230210e113.940187.hk (2017), an infrared video of a picturesque Hong Kong scene shot from the perspective of someone lying down, gazing up to watch the planes go by. Don’t be fooled by the tranquillity. Submarine fibre optic internet cables lie beneath the ground below, knowledge of which brings an uneasy sense of technology's violation of nature, and the degrees of our obliviousness to it.

These cables support the essential networks that allow us to communicate across oceans – from politicians exchanging Covid-19 statistics and scientists trading information to family group chats and constant entertainment. This “social health” is the topic of two works in the exhibition that explore the relationship between human nature – most basically defined by awareness of our mortality – and the internet, which often thrives on our weaknesses, our need for reassurance and our herd mentality.

Ye Funa. Dr.Corona Online. Artificial-intelligence doctor.

Audiences may turn to Dr.Corona Online, an “artificial-intelligence doctor” designed by Chinese artist Ye Funa, to answer their personal problems. The response is nonsensical, a muddle of words from social media discussions and “chicken soup quotes”, but it is designed to be shared with friends of course.

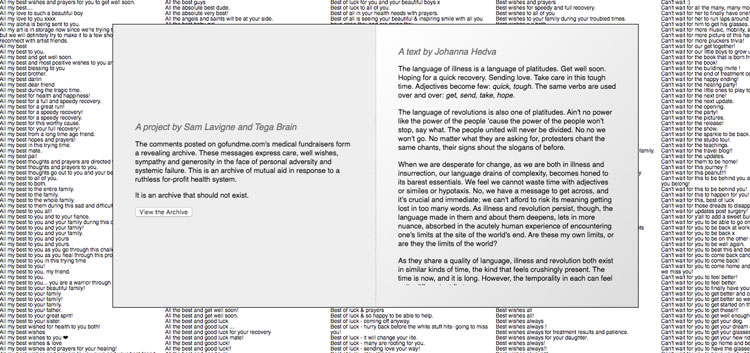

Tega Brain and Sam Lavigne. Get Well Soon!, 2020.

The second “social health” work, Get Well Soon! (2020), by Tega Brain and Sam Levigne, is a vast e-card of 200,000 well-wishes, taken from the crowdfunding site GoFundMe. A rudimentary card floats above columns of messages and opens with a short essay by the artist and writer Johanna Hedva, who discusses the all-consuming occupation of “care” during the Covid-19 pandemic, and questions whether communal care might be considered a revolutionary act. Ga describes the messages as “a dynamic aggregation of hundreds and thousands of real-time data streams with a charged political outcry”.

The skill of net art is that it can be active within the very network that it critiques. Ga says: “Under the current self-quarantine conditions, networked art revitalises a kind of virtual tactility and viscerality in the sense that it is not only a passive viewing process, but also requires an active engagement of the participant, a user v viewer experience that is unique to network-centric art. Therefore, contemplation can be reinforced by embodiment. I think that’s another kind of solace in a moment of isolation and physical restraint.”

We=Link: Ten Easy Pieces.

The exhibition’s title, We=Link: Ten Easy Pieces, is a coded formula that summarises Ga’s intent. The first part, We=Link, refers to the popular Chinese social network WeChat. Ga wanted every artwork to be accessible to anyone with WeChat, which covers any HTML5-compatible mobile platforms. The second part, Ten Easy Pieces, alludes to Five Easy Pieces, the 1970 film starring Jack Nicholson. Ga explains why: “I first saw Five Easy Pieces, I believe, in the late 80s when I was studying in Berlin. It’s always been one of my favourite movies. When I was thinking about the concept and format, somehow Jack Nicholson’s anxiety in the movie immediately came across and stuck in my head as a mental image for this show. It was like the Unbearable Lightness of Being – it was so heavy that it must find a way out. Five Easy Pieces provided such a metaphor in a time of isolation, estrangement and soul-searching.”

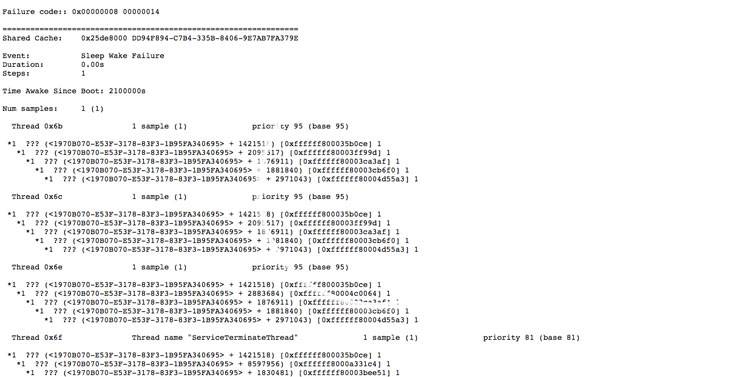

Art collective Jodi. ICTI.ME, 2020.

Many of the works capture the feeling of global anguish that this pandemic has caused. The glitchy browser deconstruction ICTI.ME (2020), by the veteran net art collective Jodi, is a jarring and uncomfortable experience. Ga calls it “browser-based psycho-visual emotiveness”.

Raphaël Bastide. Evasive.tech, 2020.

The Paris-based artist Raphaël Bastide builds inward portraits of text, buttons and graphs with varying degrees of interactivity in Evasive.tech (2020), a daily lockdown diary of digital musings and fluctuating emotions, that is both a journey and a routine. Paradoxically, as Ga says, the online world is one of both network and isolation.

aaajiao. WELT, 2020.

The tension between the individual and their community can be felt in WELT (2020) by aaajiao, a pixelated canvas that anyone can contribute to. Eventually, each pixel will be linked with blockchain encryption, usually used for privacy, an act that throws into question the meaning of the contribution beyond creativity.

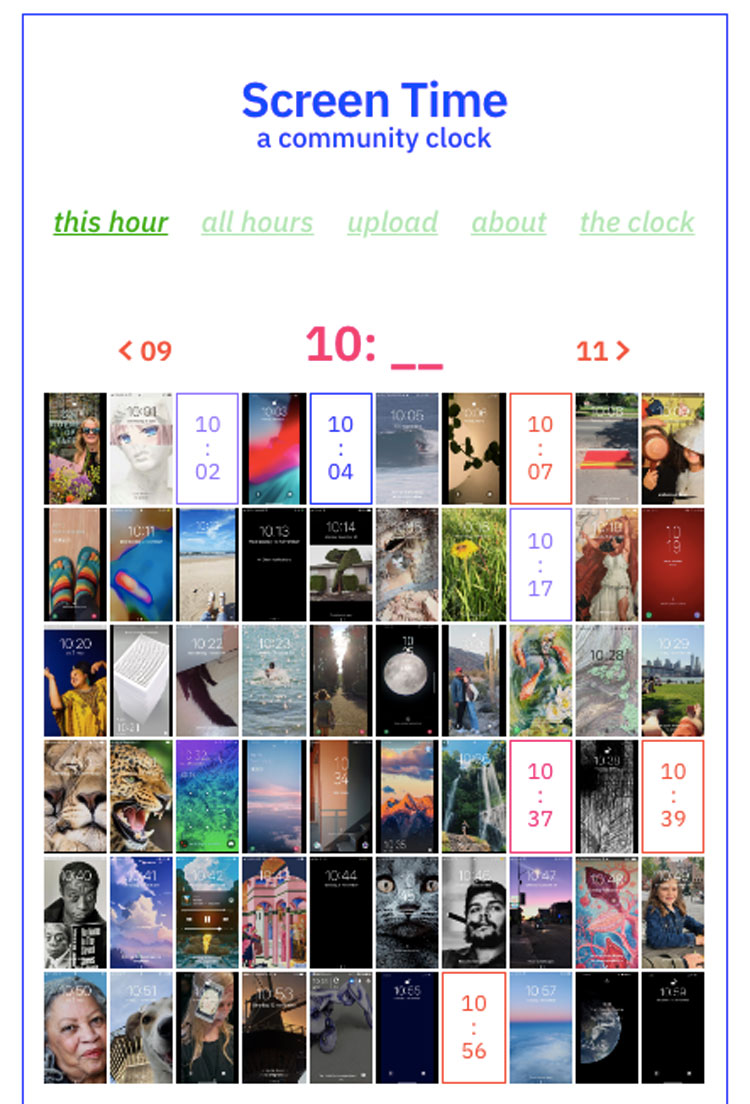

Helmut Smits. Screen Time, 2019.

Screen Time (2019), a “community clock” by the Rotterdam-based artist Helmut Smits, similarly invites participation by asking people to upload a screenshot of their phone into a minute time slot. While it inspires a sense of community, it also offers a glimpse into the lives of participants – a moment of voyeurism. That feeling of vulnerability also occurs when the green light of the webcam flicks on during artist Li Weiyi’s The Ongoing Moment (2020). Li asks users to input “mood” data into an online test that generates a “mood of the moment” filter and snaps a photo. The work ends in the option of an exchange – if you want to keep the filter, you must share it with your friends.

Li Weiyi. The Ongoing Moment, 2020.

The Ongoing Moment, LI Weiyi, 2020. Customised face filters to capture your moment.

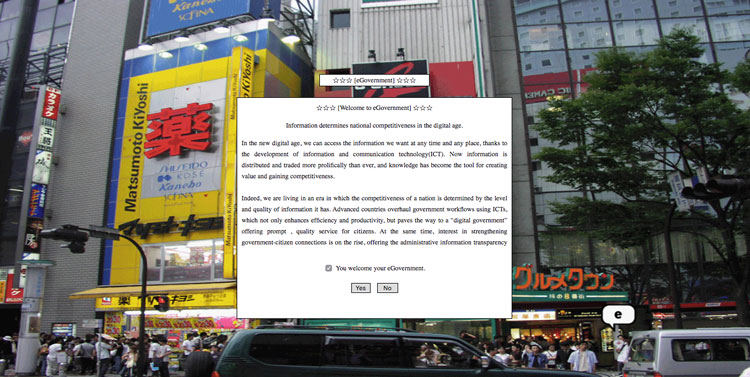

Buried in small print, hidden in cookies, or even required by law, networks often involve a data trade-off. Inspired by modern-day panopticon-style digital surveillance, the online questionnaire eGovernment.or.kr (2013, remade in 2019) by the Korean artist Yangachi gets personal, fast – requiring your father’s name, your annual income and your social security number if you wish to proceed through the work. A final tick box is an opt in or out: “Your personal information can be accessed to everyone. If you want to use information of other members, you can use it upon paying $10.”

Yangachi . eGovernment.or.kr, 2013 (remade in 2019).

Covid-19 has intensified governmental motives for communicating digitally with citizens. South Korea’s quest for a “digital paradise”, as Yangachi calls it, has resulted in advanced political communication technology, which, on the positive side, was the reason for the low death rates and its ability to contain the spread of Covid-19 compared with other countries. Yangachi’s work asks how we can navigate this safely. The collective Slime Engine shows how easily the internet can be manipulated for political propaganda, in Headlines, a news webpage that explores how headlines, which are reductive summaries of complex stories, can mislead readers.

As the internet and digital media becomes further embedded in our world, Ga sees net art like a check and balance that must be engaged with. He began his career as a media art curator in the 90s, the heyday of internet startups, curating his first online exhibition in 1998, the year that Google was founded. “I believe that a media-saturated society has to be dealt with by its very means – media technologies – economically, politically, environmentally and technologically, as well as culturally. The late German media theorist Friedrich Kittler said something quite succinct in that regard: ‘The arts (to employ an old word for an old institution) entertain only a symbolic relation with the sensory fields they take for granted. On the contrary, media relate to the materiality with – and on – which they operate in the Real itself.’”