-16.jpg)

Suzanne Treister: Prophetic Dreaming, installation view, Modern Art Oxford, Photo: Rob Harris.

by JOE LLOYD

A reclining Venus, straight out of an old master painting, gazes out of a chunky 1980s TV set that is precariously balanced on the moon. This tiny 1986 painting, Venus on TV on the Moon, is an appropriate image with which to launch Prophetic Dreaming, the first major institutional retrospective by the British artist Suzanne Treister. Although very different in medium from the works that have followed – films, diagrams, costumes, floppy disks, tarot cards, huge sculptures of UFOs, architectural installations, fictional computer games and even a playable point-and-click adventure – it provides a gateway into the concerns that have animated her work for more than 40 years. “This for me,” says Treister, “is the earliest key painting because it’s got this combination of older histories and technology and science fiction future scenarios, all in one.”

Suzanne Treister, Venus on TV on the Moon, 1986. Copyright The Artist, courtesy Annely Juda Fine Art, London and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York.

Born in London in 1958, Treister trained at Saint Martin’s School of Art and then Chelsea College of Art and Design. She began her career as a painter. Several works show Venus surveilling the world. A huge painting called A Simple Maze (1988) features a billowing sky that could come from a baroque wall fresco, divided into a grid-like labyrinth by oversized birthday cake candles, with a crimson curtain occupying the top left corner. “My work became quite popular,” she recalls, “but it was completely misinterpreted because I wasn’t a postmodern artist. I wasn’t into the death of the author and appropriating imagery for that sake. I was basically trying to make alternative narrative histories and talk about past, future, present in different ways.”

-1.jpg)

A Simple Maze, 1988 (centre), installation view, Suzanne Treister: Prophetic Dreaming, Modern Art Oxford. Photo: Rob Harris.

The early 1990s was a period of rapid advancements in computing. Treister’s boyfriend at the time was an arcade game enthusiast. She began to speculate about other purposes these technologies could be used for – a thread that runs throughout her career. She started painting works that resemble stills from video games. Some feel like direct transplants from the screen. Others are more fanciful: Koons-Kiefer Video Game No 1 (1989) features a glittered-up Jeff Koons poodle alongside rods that resemble the palm trees in Sonic the Hedgehog and the collaged reeds of Anselm Kiefer paintings. Eventually, Treister decided to go one step further. She bought an Amiga computer, and using the programme Deluxe Paint II created a series of fictional video game screens, which she then photographed and printed (1991-92).

Suzanne Treister, Fictional Videogame Stills / Would You Recognise A Virtual Paradise? 1991-1992. Courtesy the artist, Annely Juda Fine Art, London and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York.

They present an alienating, often bleak world. Many pose questions. One asks: “Have you been sentenced to a fate worse than death?”. Another is a menu screen for “The Murder Weapon”, with the word Murder written twice. The works were shown at Edward Totah Gallery in March 1992. The same year, Treister moved to Australia. “It was a very weird moment,” she says. “I heard from Totah that all these people were coming along, going: ‘What’s this?’ … I think some very young people were intrigued. And then I disappeared for 10 years.” When she returned to visit the UK over the next decade, she saw art that seemed to be influenced by her work. “By then, I was in the global new media scene, I did not really want to have anything to do with the mainstream anyway,” she says. “So, I just left them to it.”

Suzanne Treister, SOFTWARE / Sacred Vision, 1993-4. Copyright The Artist, courtesy Annely Juda Fine Art, London and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York.

In Australia, Treister returned to painting. The Software (1993-94) series comprises painted boxes and floppy disks within, which imagined a panoply of fictional computer programs at a time when most publicly available ones were business aids. The selection presented at Modern Art Oxford reveals a near-boundless world of possibility. One box features a chair with the word “Kiss” carved into its backrest, with the same word appearing on the disk. Another is furry all over, with looming eyes and a snout-like nose. One wonders what the program Solutions does. Its title drips with goo like the logo of a metal band.

-12.jpg)

Rosalind Brodsky’s Electronic Time Travelling Costumes, installation view, Suzanne Treister: Prophetic Dreaming, Modern Art Oxford. Photo: Rob Harris.

Treister’s decade in Australia transformed her work. As she explains: “Nineties London was very slow in the new media area. London thought it was the centre of the universe [and] didn’t need the internet. In Australia, it enabled an absolute paradigm shift … Suddenly, everyone in other parts of the world that were not so arrogant were communicating globally and developing this grassroots internet culture which was becoming a massive countercultural and radical political phenomenon. England just suddenly seemed tragic.” In Australia, Treister’s gaze turned from computer software to the vast potential and ramifications of the internet. She invented an alter ego, Rosalind Brodsky, a time traveller who lived between 1970 and 2058. Brodksy believed she worked at the fictional Institute of Militronics and Advanced Time Interventionality (IMATI), where she researched time travel in order to contact late psychoanalysts.

Treister’s previous projects already abounded with recurring motifs, such as the face of Batman’s Joker. But through the Brodsky alter ego she created a vast, interlinked body of work. No Other Symptoms – Time Travelling with Rosalind Brodsky (1997-99) is a CD-Rom computer game that lets you explore Brodsky’s home in Neuschwanstein Castle. There are various surreal touches, such as a group of neo-Nazis that Brodsky has imprisoned in a cake. You can watch performances by Brodsky’s band, cooking demonstrations and nightmarish adverts for genetically altered food such as Clono Chutney, which allows you to make edible clones using saliva. One video shows the white sheet-clad ghost of Sigmund Freud recounting an encounter with Brodsky to his similarly spectral daughter Anna. Treister weaves together various narratives into a beguiling, often surprising whole.

Rosalind Brodsky and the Satellites of Lvov. Band poster. Image copyright The Artist, courtesy Annely Juda Fine Art, London and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York.

The internet changed around the turn of the millennium. The CD-Rom went the way of floppy disks. The free-spirited, utopian idea of the internet had begun to give way to a corporatised one, big on making money and establishing control. Silicon Valley had been carved out. “The grassroots period of this free communication and positive action was over,” Treister recalls. “And I was getting sick of the arms race of technology.” Then began a third phase of Treister’s career, where she returned to traditional media to comment on the changing technological landscape. As Brodsky, she painted dreamlike images of her time-travelling adventures. Treister began the Nato series (2004-), watercolours that chart Nato’s classification system for objects, from livestock (not raised for food) to “perfumes, toilet preparations and powders”. “It’s a parallel universe seen through the eye of the military,” says Treister.

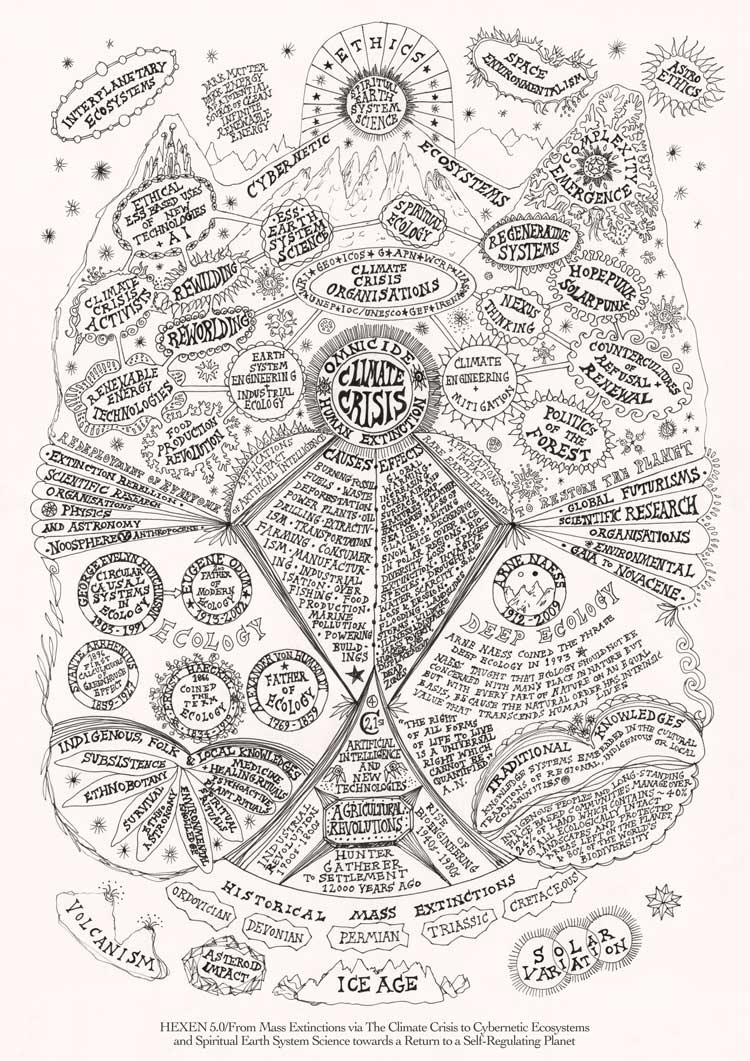

Suzanne Treister, HEXEN 5.0 / Historical Diagrams / From Mass Extinctions via The Climate Crisis to Cybernetic Ecosystems and Spiritual Earth System Science towards a Return to a Self-Regulating Planet, 2024-5. Image copyright The Artist, courtesy Annely Juda Fine Art, London and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York.

Hexen2039 (2006) explored Brodsky’s research on potential mind-control technologies developed by the British military. One component is an enormous diagram fusing text and image, which constellates the history of mind-control ideas, from the Elizabethan mathematician and occultist John Dee to Vladimir Lenin. “At the time,” says Treister, “everyone was saying you’re completely crazy, this can’t happen.” Then, after an event at the Science Museum, a scientist told Treister that the US army was trying to develop that very thing. Hexen 2.0 (2009-11) followed, a sprawling project looking at the scientific histories of mind control. “After the Hexen 2.0 project, everyone just called me a conspiracy theorist,” she says. “Then Edward Snowden arrived.” She set about making poster works ironically celebrating surveillance culture (2012). The next year she filmed an exhibition through the eyes of a drone, which gradually settled on a plinth and became an artwork.

Suzanne Treister, HEXEN 2.0/Tarot, 2009-11. Image copyright The Artist, courtesy Annely Juda Fine Art, London and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York.

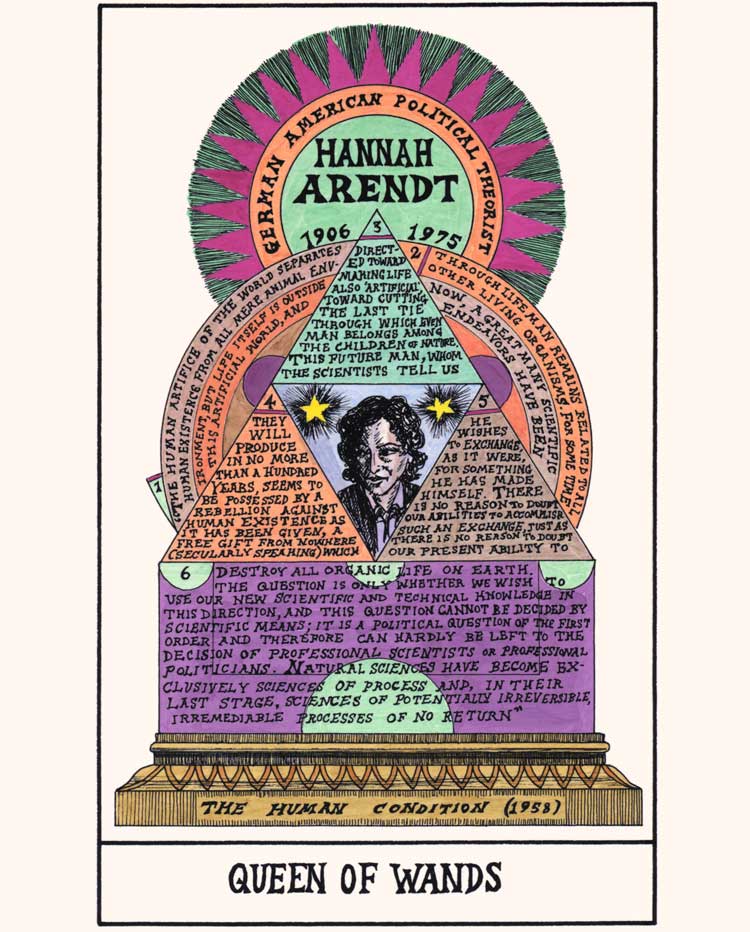

It is around this point that Treister’s art, already characterised by large-scale projects, swells to the size of a small universe. The Nato series (2004-08) comprises watercolours charting the organisation’s classification system for objects, from “livestock (not raised for food)” to “perfumes, toilet preparations and powders”. “It’s a parallel universe,” says Treister, “seen through the eye of the military.” There are currently 192 works in the series. Hexen 2.0 includes a complete set of 78 tarot cards, each of which depicts a philosophical or political response to the workings of the mind, often in a form resembling an alchemical diagram. The set packs in dozens of theoretical approaches and intellectual historical references. It is art that will make you learn – about the history of ideas, about the systems that lurk beneath society – and ponder your place within them.

As the cards demonstrate, Treister’s art has also become engaged with mysticism and the occult, and how these non-scientific systems intersect with scientific, supposedly rational knowledge. The Kabbalistic Futurism (2021-23) series features watercolours that resemble the Kabbalistic tree of life. “It’s taking those traditions and thinking about them now and into the future, and trying to work with ideas of mystical truths,” says Treister. “Because in the Kabbalah, in the Zohar, there are descriptions of what might possibly be the big bang. So, they were really working on an understanding of the cosmos but not through the kind of physics we do now.”

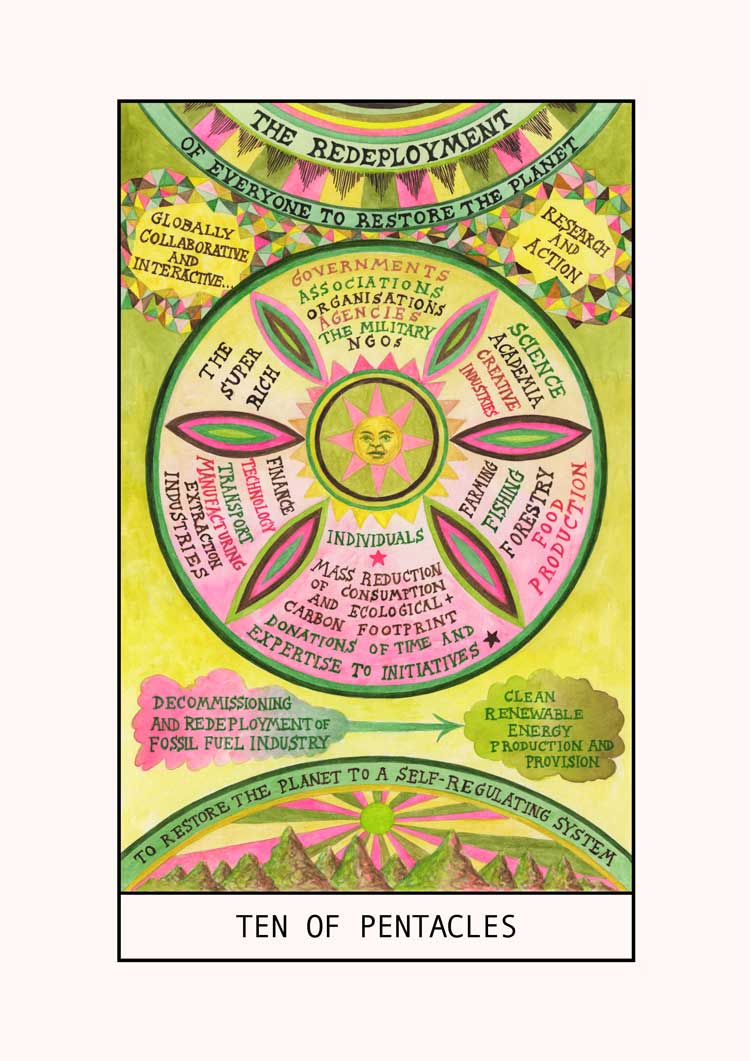

Suzanne Treister, HEXEN 5.0 / Tarot / Ten of Pentacles – Redeployment of Everyone to Restore the Planet, 2023-24. Courtesy the artist, Annely Juda Fine Art, London and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York.

Parallel to this, Treister’s work has increasingly engaged with the environment. A major public project, The Spaceships of Bordeaux (2013-22), took as one of its starting points the technologies Bordeaux uses to prevent flooding, and the discord between the city’s reliance on these machines and the writings of local philosopher Jacques Ellul, who warned that technology would overthrow us. There is now a Hexen 5.0 (2023-25), which “traces cybernetics’ relevance to whole Earth systems and how the cybernetic self-regulating feedback loops of the planetary ecosystem, which we have sent out of whack, need to be addressed through an understanding of the workings of the total global ecosystem”. It includes an updated tarot deck, whose alchemical diagrams are arguably even more elaborate than its predecessor.

The exhibition concludes with the Institute of Mystical Earth System Science (2024-25), which imagines an institution that combines disciplines to forestall climate change. Treister used AI to create pictures of various international outposts for this agency. There is also a striking set of watercolours imagining ethical AI interfaces, alien-esque beings created for tasks such as rewilding and permaculture. Does Treister think these world-saving entities might come into being? The answer is nuanced: “These works function in the brain of the viewer from where they might take effect. AI is trying to emulate the brain, and these works can be incorporated by the brain. It’s a circular thing.” Let’s hope Treister’s gift for prophecy holds true.

• Suzanne Treister: Prophetic Dreaming runs at Modern Art Oxford until 12 April 2026.