_2025_Libby-Heaney_Photo-Max-Colson-2.jpg)

Libby Heaney, Shadowscapes (Wilderness Within), 2025. Installation view, Orleans House Gallery, London. Photo: Max Colson.

Orleans House Gallery, London

9 October 2025 – 1 March 2026

by BRONAĊ FERRAN

The route by foot from the station to Orleans House Gallery in Twickenham, south-west London, edges the River Thames. It forms a perfect backdrop to the exhibition in which three lesser-known paintings by JMW Turner, renowned master of painting the dynamics of water (as well as the other elements), are featured. These are accompanied by six works by the contemporary artist Libby Heaney. The exhibition forms part of the Turner 250th birthday celebrations and brings works by him to this venue for the first time. As the small but dedicated Turner museum, also in Twickenham, documents, the artist had a close, if relatively brief, association with this area of London.

Heaney is a former postdoctoral researcher in quantum theory, who moved into art after 2013 – and, she tells me, is “no longer a scientist”. She has become known, nonetheless, as a cultural intermediary in the slippery zones in between the domains of art and science, not least in finding ways to combine dimensions of felt and embodied subjectivity within her, frequently quantum-infused, art production. That the UN has also proclaimed 2025 to be the International Year of Quantum Science and Technology under the auspices of Unesco, with multiple articles and exhibitions on how this relates to art being published and staged, in which Heaney is regularly mentioned and included, adds to the timeliness of this intervention.

In June last year, Heaney was invited to take on this commission, by Andy Franzkowiak, arts programmer at Richmond upon Thames borough council. At the opening of the show, Franzkowiak tells me that, in keeping with the venue’s general policy with respect to artistic commission, Heaney was given a free hand to decide what she wanted to do, within the given functional and logistical constraints. Hence, she was also invited to make the selection of paintings from the Tate Collection.

The exhibition effectively begins in the Grade 1-listed Octagon Room, finished in baroque-style in 1820. The room is one of only two parts of this historical building to have survived in its original state since its initial construction. Its geometrical design and hyper-real gold-leaf decoration as well as black-and-white marble flooring invite the visitor to be still and to absorb a sense of the perfect architectural proportions.

_2025_Libby-Heaney_Photo-Max-Colson-2.jpg)

Libby Heaney, Shadowscapes (Wilderness Within), 2025. Installation view, Orleans House Gallery, London. Photo: Max Colson.

Heaney places art in this room primarily by way of a four-channel sound installation entitled Wilderness Within, which conveys a sense of an ambient score dispersed around the related speakers. It emits a high degree of randomness that provokes us to listen more closely, as if to try to discern patterns among the elusive human-voiced elements intersecting with coded electronic dimensions. Heaney composed the score drawing on a publicly accessible IBM Qubit system that she started using in 2019. She worked with an artificial intelligence (AI) process to discern and then magnify particular dimensions of Turner’s paintings, based on digital prints of the three works on display, then transformed the visual images into sounds.

Installation view, Shadowscapes: Heaney, JMW Turner and Quantum, Orleans House Gallery, London. Photo: Bronac Ferran.

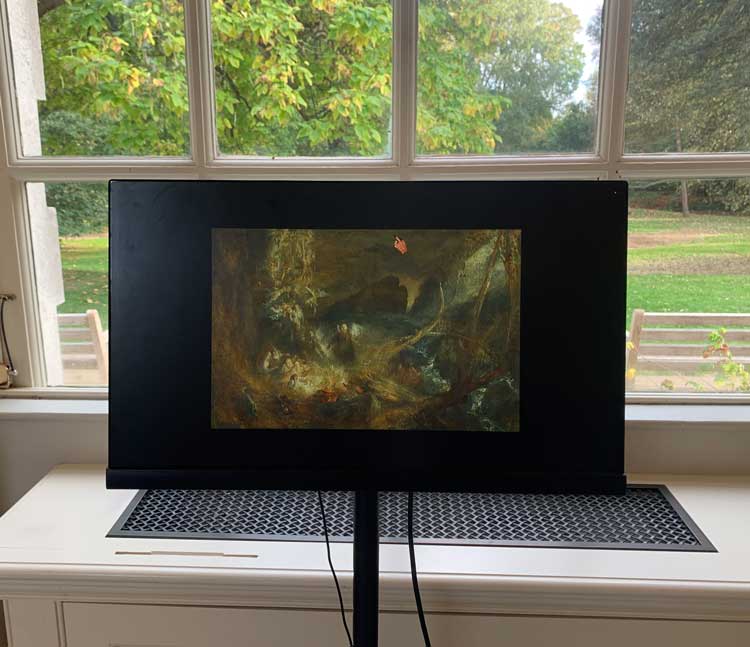

A screen facing into the gallery shows us a still digital image of one of the Turner paintings, The Vision of Jacob’s Ladder (1830), on which we can see also a small pointing hand with black-painted fingernails that does nothing if we attempt to manipulate it. The colours of this painting blend seamlessly, meanwhile, with the autumnal foliage we can see through the windows in the park outside, forming a convergence of the artificial and natural that speaks to Heaney’s attempts to collapse such binaries.

All of this is enough to make for a beautifully placed installation that frees the mind of the viewer to listen and tune into inner and outer realities, yet as if this multilayered intervention were not enough in itself, Heaney goes further to lay out on the black-and-white marble floors a set of what she describes to me as “beanbags” that people are supposed to recognise that they can lie or sit on to enhance their immersive experience. In the gallery handout, they are referred to as “soft sculptural seating”. However, they seemed to me to fall well short of being designed for sitting, instead becoming visual distractions with respect to the room’s other perfectly designed elements.

In the second room of the exhibition, we are left relatively free to focus in on the quality of what is being shown. Here, we see how Heaney is responding on a visual level to Turner with respect to two of his paintings, The Hero of a Hundred Fights (c1800-1810; reworked 1847) and the aforementioned The Vision of Jacob’s Ladder, in which Jacob is receiving an emanation from heaven, combined with an angelic presence.

JMW Turner, The Hero of a Hundred Fights, c1800–10, reworked and exhibited 1847 (detail). Installation view, Shadowscapes: Heaney, JMW Turner and Quantum, Orleans House Gallery, London. Photo: Bronac Ferran.

The Hero of a Hundred Fights was, on the afternoon I was visiting, attracting the largest group of people, drawn perhaps to the alchemical-like burst of yellow, red and green light on the left of the painting. They were puzzling also over images of what looks like industrial machinery at the centre. A certain critical and historical uncertainty coalesced in the 1840s in relation to what exactly Turner was showing here. One such commentary, according to the Tate catalogue, observed: “It pleases most when seen at various distances.”

Inclusion of this work was an excellent choice by Heaney for this exhibition, insofar as it also conveys a relationship to technology of the time (with respect to the casting of a sculpture in 1847 on top of what may have been the casting of a bell in a foundry in its earlier iteration) and to a level of ambiguity that can enter into interpretation of a work that may be reworked over time by the artist, leading to layers over layers, and to traces of one surface under another. It fits closely with what Heaney has told me is her interest in the psychological basis of Turner’s practice, and how this becomes manifest in levels of light and shade as a primary instrument of his vision. The work becomes in her reading, therefore, a way to make a connection to the exhibition’s lead thematic of Shadowscapes, as drawn from Carl Jung, where, as the exhibition description puts it: “Dissecting and investigating her own shadow self, Heaney delves into Turner’s paintings, reflecting on how they feel and the imagery they summon. She treats Turner’s paintings as contemporary psychological landscapes, holding light and shadow at the same time, coexisting as our emotions do.”

At the opening of the show, she speaks to me also of her sense that using today’s media, such as virtual reality (VR) and AI-based systems, as well as opening up to the potential of quantum computing to go beyond digital and binary constraints, facilitates a way of going beyond conventional painterly 2D surfaces to delve into deeper, multilayered possibilities. We see her testing this idea in the same space as the two Turner works already mentioned. A large screen, in front of which viewers are encouraged to sit (again on some soft furnishings) becomes a kind of vaporous mirror through and into which our images seem to meld and enter. A webcam is, in fact, capturing our movements, while Heaney, using her skills in manipulating digital imagery so that patterns appear to be transfused into open and emergent fields of light and colour, presents us with an attempted 21st-century equivalent of Turner’s depth of painterly colour and dynamic of perceptual movement on the canvas.

Installation view, Shadowscapes: Heaney, JMW Turner and Quantum, Orleans House Gallery, London. Photo: Bronac Ferran.

This is a work that seems to me to succeed in this space, being placed and scaled appropriately not to interfere with the other works, while in its own time, as we drift towards it, drawing us into its orbit and claiming our undivided attention. The title given to it by Heaney, Emotional Dumping Ground (2025), speaks again, though, to a sense of something spilling over from the space of the work into the experiential ground and body of the viewer, who is after all captured in its field of reference, simply by moving too close to it.

Also in this ground-floor gallery area, Heaney has placed one of her own water-colours, as a medium she has been using to allow for the direct expression of her own emotions, channelled directly through her hand without the use of digital systems. She has described “quantum as being close to watercolour as – unlike dry oil paint – it is never stable but rather blurry, layered and shapeshifting”. This may be read as rather an over-generalisation, not least with respect to how oils are used by Turner, to achieve many of the same effects.

She is showing three watercolours within the exhibition, all of which refer back to her sense of familial trauma, and all of which she has made this year, while simultaneously undergoing therapy and listening to the aforementioned Wilderness Within score.

_2025_Libby-Heaney_Photo-Max-Colson-2.jpg)

Libby Heaney, Family Shadow (Throat), 2025. Photo: Max Colson.

The work in question is named Family Shadow (Throat) (2025) and points to her concern to give expression to emotions as they are felt in different parts of the body, as a step that once again we might see as a balancing out through art of feelings repressed in her time spent in full-time science.

Indeed, over the last two years, within related cultural circles, Heaney has achieved a high degree of visibility for speaking out about the need for artists to get involved with quantum computing, at a time when it is becoming the primary goal of commercial and industrial-military forces. Beyond this, she has also transferred aspects of a quantum view of reality into making works in digital, material and VR formats into which she also injects embodied, performative and subjectivist elements. Considering ways that she is doing this at least on the evidence of this exhibition, it seems to me that she is trying hard to play into the logic of constrained gallery frameworks while, at the same time, exploring an aesthetic that tends towards participation and indeed breaking, breaching and transgressing the distancing frames and framings that tend to demarcate the difference between art as production and art as an experiential encounter.

We see this tension played out on the mezzanine floor of the exhibition, where Turner’s luminous Rocky Bay with Figures (c1827-30) – described in the Tate catalogue as having “infinite gradations of tone” – is accompanied by the three other watercolours made this year by Heaney. Here, as with the earlier example of her work in this medium, we gain access to her art as still in a state of becoming form rather than being formed. Indeed, in the description of the work entitled Personal Shadow (belly) (2025) she refers directly to undergoing therapy.

_2025_Libby-Heaney_Photo-Max-Colson.jpg)

Libby Heaney, Kkkccccc Eeeuuggh and Personal Shadow (belly), 2025. Photo: Max Colson.

In another of her watercolours, Golden Shadow (Hips) (2025), we see a collection of faces with eyes and mouths but otherwise without individuation. Here, she refers to having been influenced by the way Turner painted faces in Rocky Bay with Figures. From this statement, we can see how Heaney has been using this opportunity to internalise aspects of what Turner was doing, availing herself of her advanced technological skills to break down dimensions of his works into reusable data as well drawing on her own capacity for observation, so as to channel aspects of his approach into her own emergent art practices. This I see as both a form of attunement and a haunting.

Installation view, Shadowscapes: Heaney, JMW Turner and Quantum, Orleans House Gallery, London. Photo: Bronac Ferran.

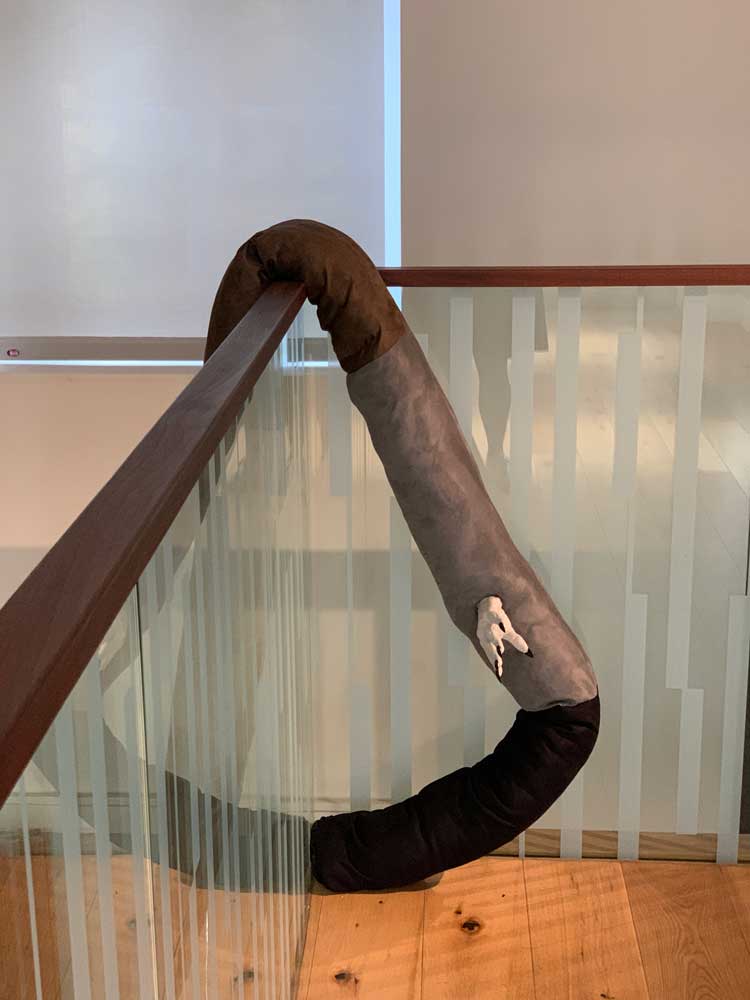

There is a wider cultural and social hauntology on the mezzanine floor, with two further soft sculptural interventions, one hanging over the balcony and the other coming out of the walls. Each again has Heaney’s signature of dislocated hands, one black and one white in this instance, both emerging out of fabric, styled to resemble long, loose limbs, slumped and divorced from the body. While appearing highly incongruous in their physical instantiation here in the gallery, such reflexively personal interventions by Heaney nevertheless find amplified presence and a heightened level of congruity in their transference to her feed on Instagram (@libby_heaney_). There, feedback focuses on the instantaneous moment of vision, dislocated in time and space from the wider gallery context.

I came away with a gnawing sense that what Heaney is perhaps testing the limits of within this exhibition are the parameters that we might generally see as applicable to showing art within a gallery. Whether what she is doing makes sense or not to all who visit the exhibition, she is succeeding in signalling that these, too, like other systems by which we think we organise our world, are always open to being extended, or subverted or even tipped over into chaos. It seemed then somehow apt that in wending my own way back to the station, I found the road I had come along, close to the edge of the river, was now unpassable, due to its spilling over.