Sarah Lucas, Sandwich, 2004-20. Courtesy the artist and Sadie Coles HQ, London. © Sarah Lucas.

Tate Britain, London

28 September 2023 – 14 January 2024

by BETH WILLIAMSON

Sarah Lucas: Happy Gas is a rollercoaster of an exhibition. As soon as you walk through the gallery door it slaps you on the cheek, then it slaps you again. It is raucous, bawdy and cheeky. It is sexy, sweary and crude. It is laugh-out-loud funny in parts, but it’s a hugely serious comment on our experiences of sex, class and gender, as well as exploring mortality and the human body. Love it or loath it, Happy Gas was conceived in close dialogue with Lucas, so this major survey is wrought in her own voice.

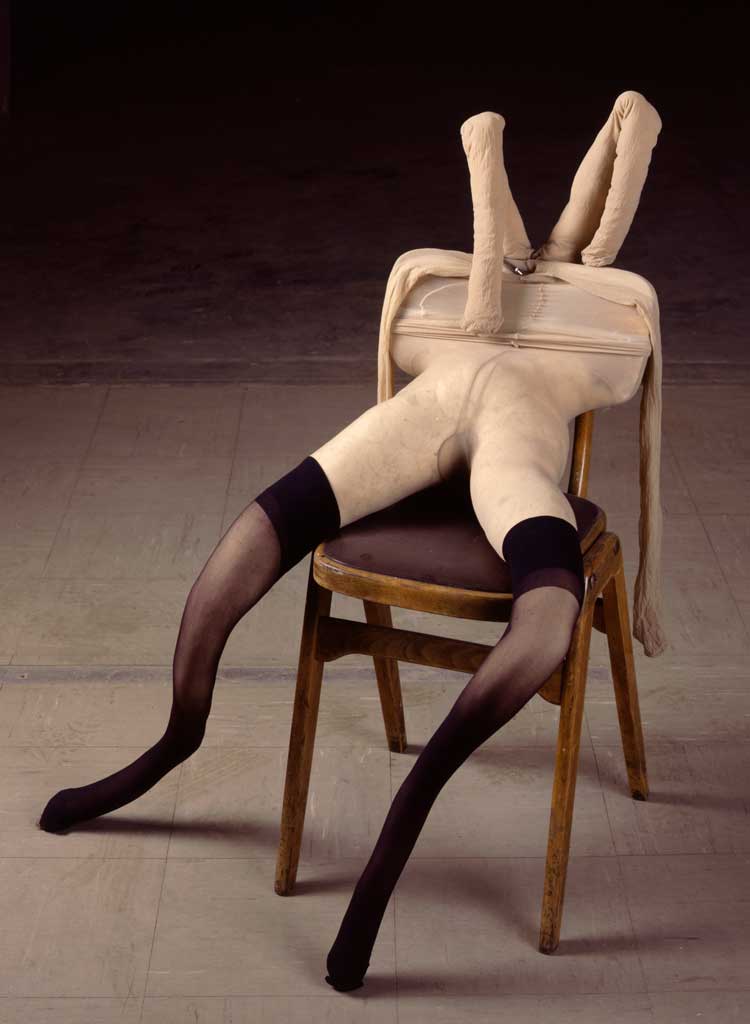

Sarah Lucas, Bunny, 1997. Private collection. Courtesy the artist and Sadie Coles HQ, London. © Sarah Lucas.

From her early tabloid newspaper works of 1990, and her early bunny work Bunny (1997), through to sculptures from 2019 to the present day, this is, in a sense, the artist’s own summing up of her career, and she does not hold back. Lucas’s work fills four rooms, seeming strewn in every possible space and often tricky to move around. It often feels as if we were in the midst of some sordid stage play, never more than an arm’s length from a pair of stuffed tights, a cigarette or a provocatively positioned phallic symbol. Then there is Lucas’s play with language and a poke in the eye for the patriarchy. Even the exhibition’s title, Happy Gas, could have multiple meanings. It could be a reference to the endemic use of nitrous oxide (also known as laughing gas) and the press headlines associated with that. It might prompt thoughts of conventional uses of the gas in dental surgeries and labour wards. Or it might be a gesture to those joyful times in the company of others when we quite simply “have a gas”.

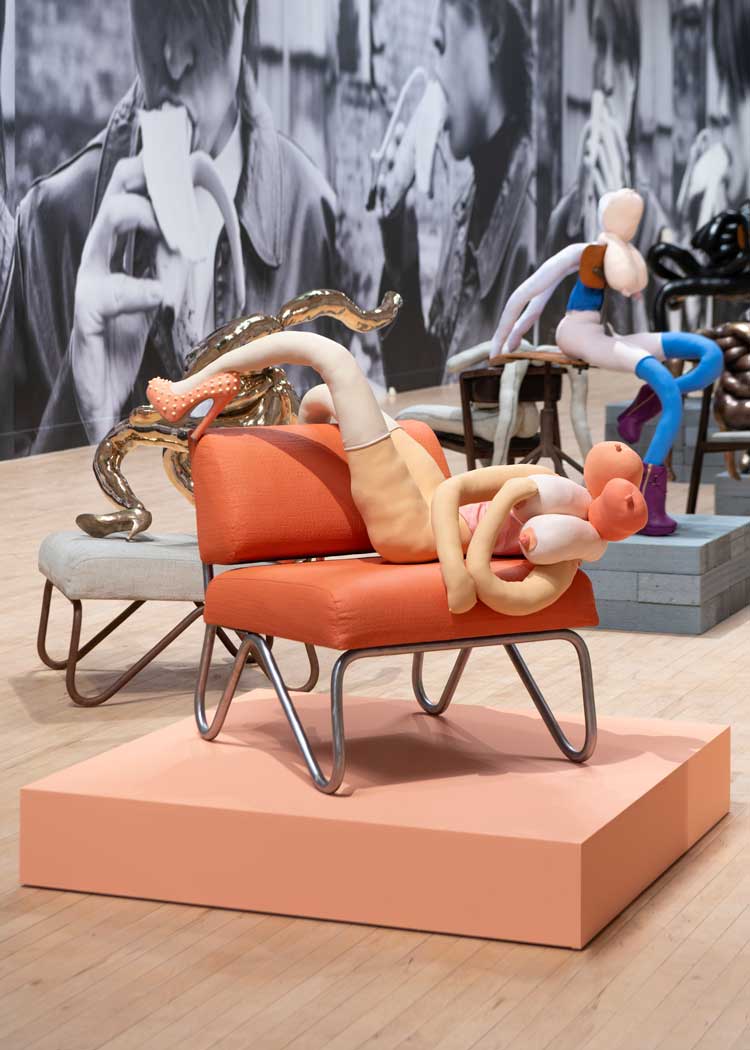

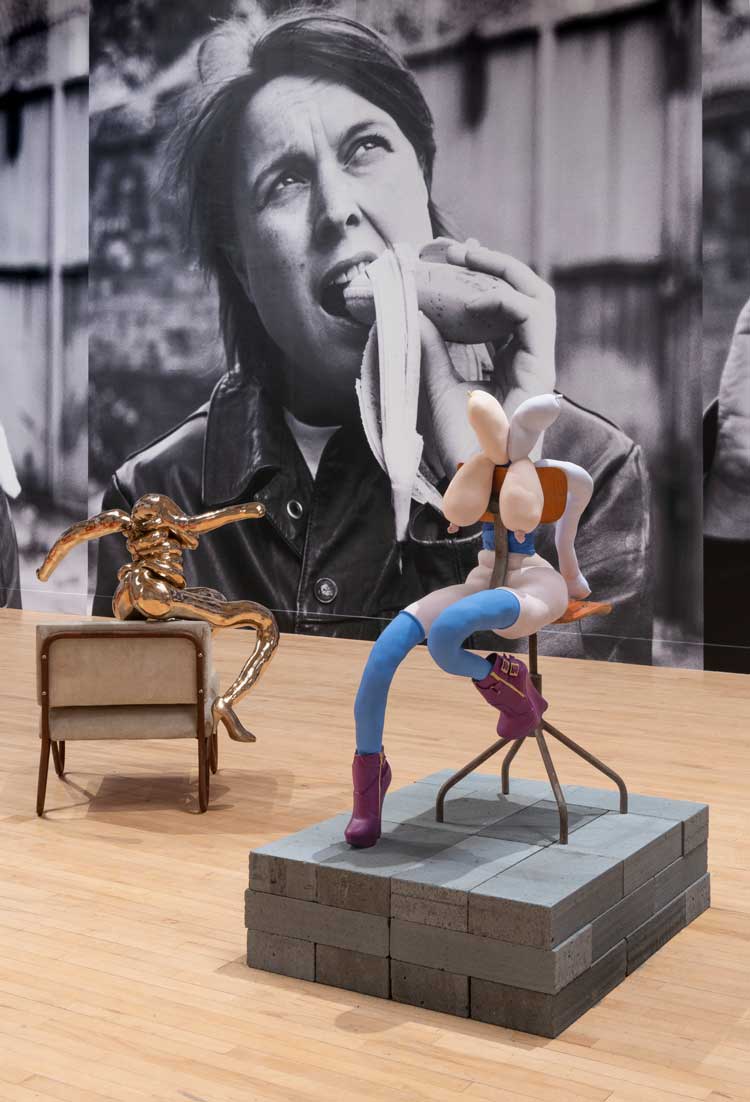

Sarah Lucas, Happy Gas, installation view, Tate Britain, 2023. Bunny Rabbit, 2022, Zen Lovesong, 2023, and Goddess, 2022. © Sarah Lucas. Photo © Tate (Lucy Green).

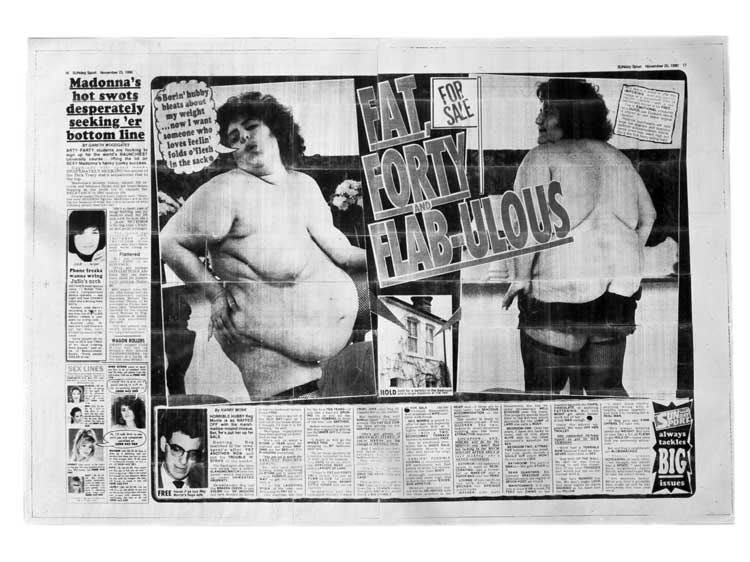

Chicken Knickers (1997) – here enlarged to fill an entire wall – stares you in the face as you enter the exhibition, and there is no doubt about what lies ahead. The image shows the artist’s lower body wearing a pair of white knickers with a raw chicken carcass attached to the front so that the carcass is a substitute for her genitalia. On another wall are enlarged versions of the artist’s tabloid newspaper works from the early 1990s, which still shock with their images and headlines: Sod You Gits, Pairfect Match, and Fat, Forty and Flab-ulous.

Sarah Lucas Fat, Forty and Flab-ulous 1990. Collection Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Gift of the D.Daskalopoulos Collection donated jointly to the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 2022. Courtesy the artist and Sadie Coles HQ, London. © Sarah Lucas.

Perhaps they are so astonishing because the articles (taken from newspapers at the time) would simply not be countenanced now. The exhibition wastes no time in introducing Lucas’s signature use of chairs with The Old Couple (1992) setting the tone as a set of false teeth stand in for female genitalia – a humorous play on vagina dentata myths that might have even Sigmund Freud chuckling.

There is more humour and horror in the next room where Lucas’s Eating Banana (1990) has been digitally reproduced as wallpaper, covering three of the four walls and dominating the room. Its incongruous scale is rather amusing. Running down the centre of the space is a large group of 20 or so chair sculptures – some old, some new.

Sarah Lucas, Happy Gas, installation view, Tate Britain, 2023. Zen Lovesong, 2023, Goddess, 2022, and Eating a Banana, 1990. © Sarah Lucas. Photo © Tate (Lucy Green).

This has been likened to a fashion runway, but the age-old sculpture court is evoked as well. As Lucas explains it: “The purpose of chairs (in the world) is to accommodate the human body sitting. They can be turned to other purposes. Generally as a support for an action or object. Changing light bulbs. Propping open a door. Posing. Sex.” Her explanation gives some sense of the variety of sculptures here. There is an insolence to these lumpy figures. Headless, slung provocatively over their supporting chairs, sometimes elevated on a plinth of some sort. While stuffed tights form the bodily structures of Bunny (1997) and many of her sisters, Lucas plays with other materials, too, so that later works sometimes use concrete or bronze. It is this play of hard and soft that sustains the relentless and wonderfully crude inuendo in the artist’s work.

Sarah Lucas, Happy Gas, installation view, Tate Britain, 2023. © Sarah Lucas. Photo © Tate (Lucy Green).

Similar themes continue in the next room with various photographs of Lucas on the walls including Stooks (2023), which shows the artist sitting in a cornfield in Suffolk where she has lived for more than a decade. Nothing else in the room suggests a shift in her work to a rural idyll, rather discomfit and strangeness is everywhere. Eames Chair (2015) is made of concrete. William Hambling (2022) is an impossibly large cast-concrete marrow (to match the pair – Florian and Kevin, 2013 – sitting on the lawn outside Tate Britain). Sadie (2015), a cast of the lower half of a female body, sits astride a large pipe. The figure faces Mumum (2012), a curious egg-shaped chair entirely covered in soft stuffed tights, tied off short and resembling breasts.

Sarah Lucas, Happy Gas, installation view, Tate Britain, 2023. This Jaguar’s Going to Heaven, 2018, and Red Sky portraits, 2018. © Sarah Lucas. Photo © Tate (Lucy Green).

The exhibition’s fourth and final room is chaotic and overwhelming. Once more we are surrounded by digitally-enlarged photographs of Lucas that have been made into wallpaper. You might call it a crescendo to the exhibition, or you might feel it is just too much. At its centre is This Jaguar’s Going to Heaven (2018), a burned-out car, broken in two and covered in cigarettes. Lucas has said: “When I first started using cigarettes in art it was because I was wondering why people are self-destructive. But it’s often destructive things that makes us feel most alive.” Of course, there is the phallic nature of the cigarette and the car, too.

Sarah Lucas, Exacto, 2018. Courtesy of the artist and kurimanzutto, Mexico City / New York. © Sarah Lucas.

In Exacto (2018), illuminated fluorescent light tubes pierce through the back and seat of a red leather chair that stands in for the female body and the violence that misogyny wreaks on it. We seek evidence of that in the news on a daily basis. Still, should the whole thing become too much to endure, Lucas dots the spaces with black cats – because who doesn’t love a cat in art? Seriously, this is not an easy exhibition to stomach, but perhaps that is why it is important.

Sarah Lucas, Happy Gas, installation view, Tate Britain, 2023. Fat Doris, 2023 and Tit Tom 2, 2023. © Sarah Lucas. Photo © Tate (Lucy Green).