Henri Matisse. The Red Studio, 1911 (detail), Issy-les-Moulineaux. Oil on canvas, 181 x 219.1 cm. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Mrs. Simon Guggenheim Fund.

Museum of Modern Art, New York

1 May – 10 September 2022

by MARIE POHL

In the winter of 1911, Henri Matisse picked up his brush and with quick strokes covered two-thirds of a finished painting in a Venetian red.

Matisse speaks and thinks in colours. He dazzles you with blues, greens, yellows, pinks and purple-browns. But that Venetian red said something the artist could not quite understand. No one, not even Matisse himself foresaw the scope of its significance in modern art.

“An artist … should not copy the walls, or objects on the table, but he should, above all, express a vision of colour, the harmony of which corresponds to his feeling,” Matisse told the American painter Clara Taggart MacChesney in an interview for the New York Times in March 1913.

What was the feeling that struck Matisse when he painted Venetian red over blue walls, pink floors and yellow furniture on the painting that came to be known as The Red Studio? It couldn’t have been fury: it is not an angry red. Nor lust: it is not lipstick red. It’s not panic red either. The tone is earthy, calm, yet insistent and strangely omniscient.

Henri Matisse. The Red Studio, 1911, Issy-les-Moulineaux. Oil on canvas, 181 x 219.1cm. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Mrs. Simon Guggenheim Fund.

The painting depicts Matisse’s studio, or rather a part of his studio. His artworks hang on and lean against the walls. Some furniture and objects are present. There is a curtained window, but no view, no way out. We are submerged in the mysterious red room for ever. Time doesn’t exist. The grandfather clock lacks hands. Perspective is obscured. The red has dyed the corner of the studio and flattened the surface. There is depth though. A thin line marks the floor. The table in the front is larger than the chest of drawers in the back. But the furniture is soaked in red. Only traces of yellow edges allude to their purpose. The red is everywhere, except for the objects and the artworks, which remain themselves, glowing in their own colours, like stars in a Venetian red sky.

A young Italian woman wants to see the painting. “It’s one of those iconic pieces,” sighs her companion. “I’d rather check out something new.”

“I just absolutely love that red,” the signora muses as the two ladies enter the museum.

On Labour Day weekend, I have rushed to visit The Red Studio at New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) before the show travels to Copenhagen, where it opens at the National Gallery of Denmark (Statens Museum for Kunst; SMK) in October. The two museums collaborated to mount an exhibition centred on Matisse’s masterpiece. For the first time, The Red Studio is shown together with the surviving art rendered in it. The curators spent four years assembling this treasure box, with works on loan from institutions in Europe and North America. And, more, they tell the painting’s unusual and inspiring history.

Quotes decorate the hallway leading to the entrance. They are taken from a letter Matisse wrote to his patron, the Russian art collector Sergei Ivanovich Shchukin (1854-1936), who commissioned The Red Studio.

“The painting is surprising at first sight. It is obviously new.” And: “Have I told you that the painting represents my studio?” And: “The whole is Venetian red.”

Light floods the hallway. Underneath the quotes, leather benches face a wall of windows overlooking the museum’s sculpture garden and the buildings on East 54th Street. They remind me of Matisse’s many windows with views on to gardens.

Henri Matisse, Alvin Langdon Coburn, May 1913. Digital positive from original gelatin silver negative; negative 9 x 12cm. George Eastman Museum, Rochester, N.Y., Bequest of Alvin Langdon Coburn. © 2022 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

I enter a grey-toned foyer, set up between the two principal galleries. There is Matisse in an enlarged black-and-white photograph taken by Alvin Langdon Coburn in 1913. The artist sits on the steps of his studio, sketching perhaps the sculpture beside him, looking down, concentrating. His dog is turned to the viewer, as if he’s asking, who are you? How dare you disturb my painter at work! Behind the open door waits the atelier Matisse portrayed in The Red Studio.

The place is Issy-les-Moulineaux, a Parisian suburb on the bank of the Seine. Matisse moved here with his wife and three children in 1909. His studio was custom built on a parcel of land next to the new family home. It was a dream come true for Matisse, who had braved years of hardship and poverty. At the age of 25, still an unknown art student, he fathered his first child, a daughter. Soon after, two sons followed. The painter worked in rented studios, often in tiny apartments, struggling to feed his young family.

Henri Matisse, Studio Under The Eaves. 1903. Oil on canvas, 55.2 x 46cm. Fitzwilliam Museum Cambridge, UK. Photo: Marie Pohl.

Studio Under the Eaves (1903) captures one such difficult moment in his life. Financial distress had driven him out of Paris back to his hometown in the dismal region of north-eastern France, where he was born on New Year’s Eve in 1869. His time of fireworks had not yet come. The modest studio feels like a cell, drenched in muddy brown colours. Shadows dominate the room. The joy is outside, not inside. The view through the window smiles in the delightful colours that will brighten his later paintings. There is hope on the horizon.

The exhibition is divided into two main galleries: The Studio gallery presents The Red Studio and the artworks limned in it. The Story gallery tells the painting’s biography, organised in chapter-like sections, offering photographs, handwritten letters, newspaper articles and other theme-related paintings by Matisse.

The Story

The Story begins with the birth of the studio. A map of Matisse’s property in Issy-les-Moulineaux is blown up to cover an entire wall. Framed, handwritten proposals from the director of the construction company discuss the structure, dimensions and materials.

Installation wall showing Letters from Director of Compagnie des Constructions démontables et hygiéniques to Henri Matisse, 2 June 1909, 16 June 1909 and 22 September 1909. Photo: Marie Pohl.

“Following your visit,” the first lines of the letter from 2 June 1909 read, “we have the honour to inform you that we would be able to provide you with a demountable studio based on the adjacent drawing, namely: Dimensions 10 metres x 10 metres … height of the walls 5 metres, shed-style roof …” The studio could be set up within two months.

It was going to be simple, spacious and practical. The framework would be iron, the roof of corrugated sheet metal, the ceilings made from wood, the floors of red fir and fir-wood panelling on the walls. Matisse requested openings to circulate the summer air, and a chimney for a stove for the winter. An architectural drawing details a wide double door and glass panes on the north side of the roof adjoining glass panes on the wall, creating a skylight to catch the indirect northern light favoured by painters.

The founder of the construction company was a former military engineer, advertising in his letterhead “fournisseur des ministres de la guerre” (supplier to ministers of war). It turned out to be an eerie omen – during the first world war, French military officers would be stationed in the studio for two years.

The map also indicates Matisse’s garden, a sanctuary for the master of colours. In her 1913 interview with him, MacChesney described the garden with “beds of flaming flowers”.

The garden, the new studio, the three-storey family home were all financed by the continuous commissions Matisse received from Shchukin, a Russian textile merchant whom he had met in 1906. The artist had shown Open Window and Woman with a Hat in the 1905 Salon d’Automne exhibition, for which he was nicknamed “fauve”, or “wild beast”. Shchukin visited the Paris art salons often. He had been collecting French paintings for a decade, starting with Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Edgar Degas, then Paul Cézanne and Paul Gauguin. Enamoured with Matisse’s Le Bonheur De Vivre (Joy of Life) (1905), Shchukin asked to visit the painter in his studio. Matisse described the day to his friend, the critic Tériade:

“Shchukin, an oriental cloth importer, was about 50. He was vegetarian and extremely sober. One day he came to the Quai Saint-Michel to see my paintings. He noticed a still life. ‘I’ll buy it. But first I need to take it home for a few days and if I can stand it, and if it still interests me, I’ll keep it.’ I was lucky that he didn’t weary of my still life. He came back and commissioned a series of big paintings to decorate his palace in Moscow. After that he asked me to do two decorations for the staircase of his palace. And that was when I painted La Musique and La Danse.”

Between 1906 and 1914, Shchukin bought 37 paintings from Matisse. “The Red Studio,” the show catalogue explains, “like all of Matisse’s large-scale works of these years, would owe its genesis to their singular relationship.”

Pink Room of the Trubetskoy Palace with Matisse's annotations, c1911. Photograph

Private Collection. Courtesy of Henri Matisse Archives. Installation view photo: Marie Pohl.

Two installation walls are dedicated to the devoted patron. Black-and-white images of Shchukin’s Moscow mansion, the Trubetskoy Palace, take you back to the grandeurs of pre-revolutionary Russia, the mansion covered in snow, or the opulent dining hall with paintings by Gauguin and Matisse on the walls. Of all the artists Shchukin collected, Matisse was the only one to whom he dedicated an entire room. He called it The Pink Room. The framed photograph of it was taken when Matisse visited Moscow in November 1911. The artist’s annotations on the photograph suggest the positions of more paintings he was going to send.

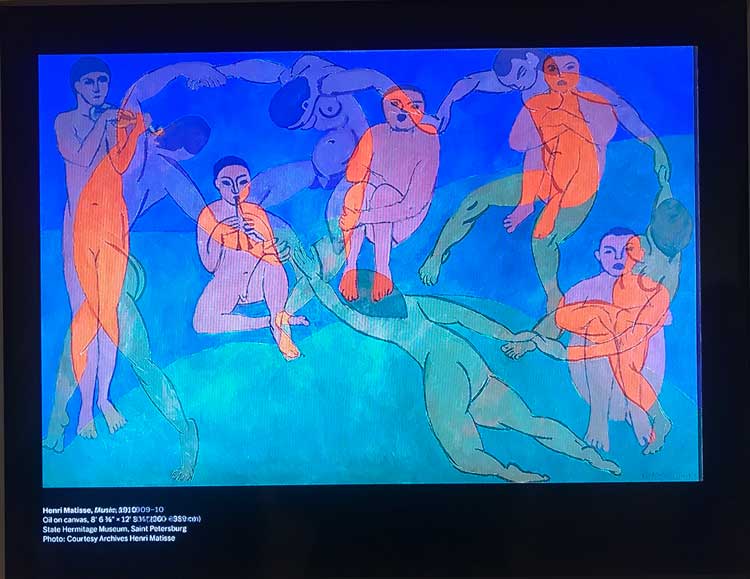

It was unusual for Moscow merchants to buy works by avant-garde French painters. Shchukin was one of few, and the only one to open his private collection to the public. People were appalled when they saw paintings such as Music (1910). In the late tsarist Russia, music meant orchestras, ballet, chandeliers, elegance par excellence. Matisse had stripped away tutus and tuxedos, and painted five naked, grumpy figures on a hill, playing a flute and a fiddle. The painting can be seen here as a digital image on a screen as part of the slideshow on the “patron wall”, presenting several Matisse works Shchukin had in his mansion.

Overlapping digital images on screen of Dance II (1909-1910), Oil on canvas, 260 x 391cm and Music, 1910, Oil on canvas, 260 x 389cm, State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg, Courtesy of Henri Matisse Archives. Installation view photo: Marie Pohl.

It’s beautiful to watch these paintings overlap, like Music (1909-1910) and Dance II (1909-1910), the two initial staircase commissions. Shchukin understood the riveting presence within the seeming simplicity. He was a man of great sangfroid. He bought what his gut told him to buy, no matter what anyone else thought. “I don’t choose paintings. Paintings choose me.”

The bond between Matisse and Shchukin was further strengthened by their shared love of textiles. Shchukin’s company, one of the largest wholesale and manufacturing companies in Russia, sold cotton, wool, silk fabrics and household linens. Matisse had grown up in Bohain in northern France, noted for its textile production. His family had worked as weavers for generations. Matisse collected textiles and portrayed them constantly. Patterns, cloth, tapestries, embroideries, the legacy of the weavers is everywhere in his art.

Henri Matisse, Still Life with Geraniums, 1910. Oil on canvas, 93 x 115cm. Pinakothek der Moderne, Munich. Installation view photo: Marie Pohl.

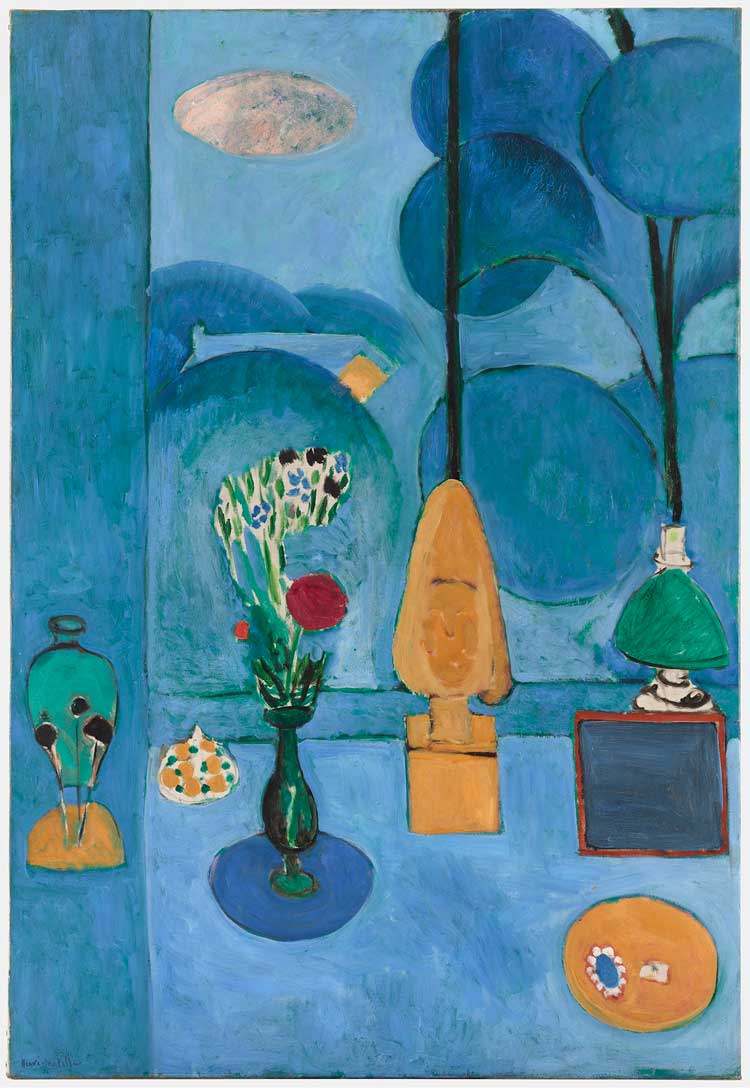

A floral textile stars in Still Life with Geraniums (1910). Peeking through the window is a patch of night sky. A pot of geraniums is witnessing the textile move across the table. The blue panelled walls and the ochre-coloured floorboards indicate the scene is taking place inside the Issy atelier. The red country table is the same one as that in the far-right corner of The Red Studio. Next to it, The Blue Window (1913) captures another moment in Issy-les-Moulineaux. Matisse painted it in his bedroom. The window looks out on to his beloved garden. The studio is tucked away behind the trees, the light still turned on. A cloud hovers above. The supremacy of colour in this and other works from that time, was unparalleled in art. Matisse had freed colour from its descriptive purpose to be an expression in and of itself.

Henri Matisse, The Blue Window, 1913. Oil on canvas, 130.8 x 90.5cm. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Abby Aldrich Rockefeller.

“A tree like a bunch of balloons … The blue fills them … The blue has come to stand for all colour, all but its precious antithesis, the golden ochre,” writes Lawrence Gowing in his book Matisse, in which he also states, “1911, the greatest year’s work” Matisse ever did.

In January 1911, Shchukin sent a letter. He requested three paintings for another room in his Moscow mansion. “It’s not large,” he wrote, and added in a postscript: “I am a little mistreated because of you. People say that I am doing harm to Russia and to Russian youth … But one day, I hope to be proven right, but it will take a few years of fighting. The subject of the three panels is yours to choose.”

Each painting had to measure 180 by 220cm to precisely fit on to the walls, and was to depict a variation of the same subject. Shchukin made a few suggestions: “What do you think of youth, adulthood and old age? Or spring, summer, and autumn?”

Matisse turned to one of his signature motifs, the studio interior. His studio renditions are a kind of self-portrait, reflective of his current mood and artistic style. Shortly after the death of Matisse in 1954, Picasso painted a series of empty studios, directly based on, and in honour of, him.

The workplace was sacred to Matisse. In numerous interviews, he speaks about believing in God, when he is working. He defined himself primarily as a modest, working family man, unlike his scandalous friend and rival Picasso. Most photographs show a serious Matisse next to an easel, painting, sketching, sculpting, or with scissors in his hands.

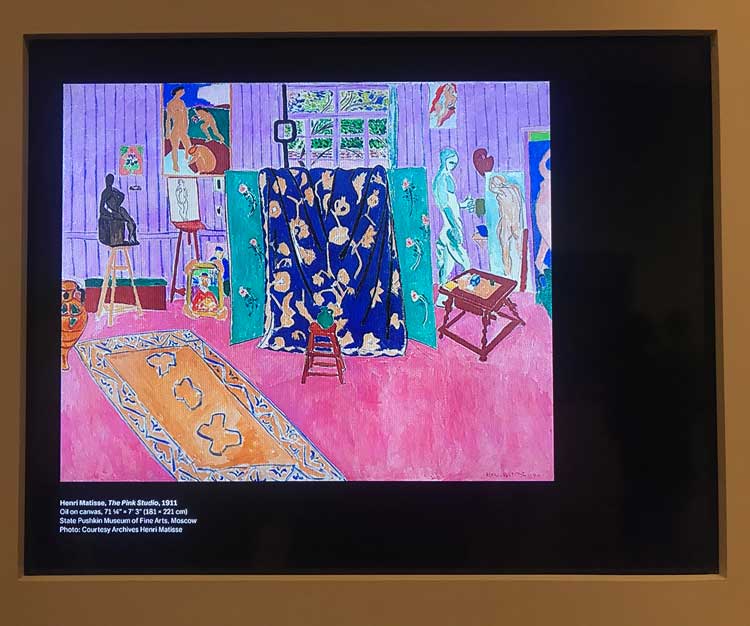

Screenshot of The Pink Studio, 1911. Oil on canvas, 181 x 221cm. State Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, Moskau. Photo Courtesy Archives Henri Matisse. Installation view photo: Marie Pohl.

The first panel he made for Shchukin’s commission was The Pink Studio (1911). A floral-patterned tapestry drapes over a folding screen in the centre of the room. The mood is cheerful, spring-like with sunshine, trees and a blue sky outside the window. Perspective is intact. The pink dominates, but the colour restrains itself and doesn’t devour the walls and floors as the Venetian red does in The Red Studio.

Today, the painting is located at the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts in Moscow. You can view a digital image on “the patron wall”, or study a small print next to a diagram that precisely indicates which parts of the atelier are depicted in The Pink and which in The Red Studio.

I wish the curators had enlarged a photograph of The Pink Studio as they did with the map of Matisse’s property. It is interesting to see the two studios together and wonder what colour Matisse would have chosen for the third panel. There were going to be three …

Between the end of December 1911 and early January 1912, Matisse wrote to Shchukin to say that he had finished the second panel. Shchukin asked to see a watercolour drawing of it. On 1 February 1912, Matisse sent the drawing from Tangier, Morocco, along with a letter, which has survived only in draft form. “This colour serves as a harmonic link … This red, which is a little warmer than red ochre, is a precise colour of the palette.” The artist’s detailed description of his painting is filled with crossed-out sentences. They could suggest a sense of insecurity, or simply be Matisse-typical revisions, as he often altered his work and writings.

Shchukin responded with a brief note. The painting “must be very interesting”. But he reckoned that he now, “preferred paintings with figures”.

His commissions were not binding. The plan for the three panels was dropped. Shchukin purchased four other paintings instead. Matisse didn’t show The Red Studio at the Salon des Indépendants, where he had presented The Pink Studio a year before. He also didn’t send it to the Sonderbund International Exhibition in Cologne, nor the Moderner Bund at the Kunsthaus Zürich.

When the Russian Revolution broke out in 1917, Lenin personally expropriated Shchukin’s art collection. He allowed Shchukin to remain in the servants’ quarters of his own mansion as a caretaker. That same year, Shchukin fled Moscow for Paris, where he died in exile in 1936. His collection is now divided between the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts in Moscow and the Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg.

.jpg)

Henri Matisse, Portrait of Sergei I. Shchukin, 1912. Charcoal on paper, 49 × 30.5cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art New York, The Pierre and Maria-Gaetana Matisse Collection. IPhoto: Marie Pohl.

During his visit to Moscow in 1912, Matisse had made a charcoal sketch of Shchukin in preparation for a portrait that was never realised. He gave his patron accentuated lips and cat-like whiskers. The eyes are two dark holes. The facial expression is assertive and refined. “That drawing had an Asian character that Shchukin didn’t like,” Matisse told Pierre Courthion in Chatting with Henri Matisse: The Lost 1941 Interview. “He aspired to be European above all else. I brought out the Asian character in him and it got a little under his skin, I think. But, as Bonnard says, portraits always become good likenesses in the end.”

The same holds true for The Red Studio. But the road to worldwide likeness took decades. The exhibition chronicles the journey that the rejected painting now embarked on.

A framed shipping receipt from the Grafton Galleries documents 12 paintings Matisse sent to London in the autumn of 1912 for the Second Post-Impressionist Exhibition, among them Panneau Rouge (Red Panel), as he had originally titled the painting. More than 50,000 people visited the Second Post-Impressionist Exhibition and not one bought a Matisse. But his work caught the eyes of two Americans, looking for art to present in their Armory Show in New York, Boston and Chicago. One year later, Panneau Rouge and other Matisse works crossed the Atlantic. Two of these paintings are presented here – Goldfish and Sculpture (1912) and Nasturtiums with the Painting “Dance” I (1912).

Henri Matisse, Nasturtiums with the Painting 'Dance' I, 1912. Oil on canvas, 191.8 × 115.3cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Scofield Thayer 1982. Photo: Marie Pohl.

In Nasturtiums with the Painting “Dance” I (1912) something is off. The work shows Matisse’s studio. We see Dance I in the background. A chair and a yellow stool with a vase holding a nasturtium stand in front of it. The back leg of the stool rests on the grass of the painting. How can the leg of the stool in front of the painting be inside the painting? Because the entire image is a painting. It’s not real.

I remember the story the art historian Ernst Gombrich told about Matisse. Someone complained to the artist that the arm of a woman in one of his portraits was too long. “Madam, you are mistaken,” Matisse replied. “This is not a woman, this is a painting.”

The American audience was enraged by the unsettling artistic realities the Armory Show presented. None of Matisse’s works sold. They were bashed as “lunatic” and “primitive”. One critic called the furniture and figures in Panneau Rouge the “reckless drawing of a child”. Students at the Art Institute of Chicago burned copies of Matisse paintings.

Panneau Rouge went back to Europe. An art dealer, who had seen it at the Armory in Boston, tried to sell it in Germany. He changed the painting’s name from Panneau Rouge to Atelier Interior. It didn’t help. No one wanted it. In January 1914, Atelier Interior returned to Matisse. The painting’s whereabouts over the following 12 years are uncertain. The first world war darkened Europe. Matisse’s studio in Issy-les-Moulineaux housed French army officers. The artist and his family moved to Paris into the same building on the Quai Saint-Michel in which they had lived years before. Later they relocated to Nice in southern France.

Henri Matisse, Studio, quai Saint-Michel, 1917. Oil on canvas, 146.1 x 116.2cm. The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C. Photo: Marie Pohl.

While still in Paris, Matisse painted Studio, Quai Saint-Michel (1917). The nude model rests on the bed, her body tenderly illuminated by the light. The sketch on the easel is barely started, the pictures on the wall are blurry, vague and unfinished, as if the artist can’t get any work done, unable to paint during the troubled time.

Studio, Quai Saint-Michel may be Matisse’s most vocal painting. Here he hints, ever so lightly, at the unfolding tragedy of war. Unlike many of his contemporaries, Matisse did not comment on conflicts, social affairs, or events. He did not sign his name on manifestos, express anger in his paintings, or get involved in political debates. In his studios, he created his own world with its own planetary system. The documentary Henri Matisse – Voyages cites the French poet Dominique Fourcade, as he described the artist: “He plunges into the sealed universe of his paintings and shuts himself away in it … Matisse paints a world of waiting. Time drags.”

In September 1927, The Red Studio moved to a nightclub in London. The owner was 25-year-old David Pax Tennant. He wanted to decorate his new ballroom with the masterpiece. Two years later, the British aristocrat also bought Studio, Quai Saint-Micheland hung it in a bar on another floor.

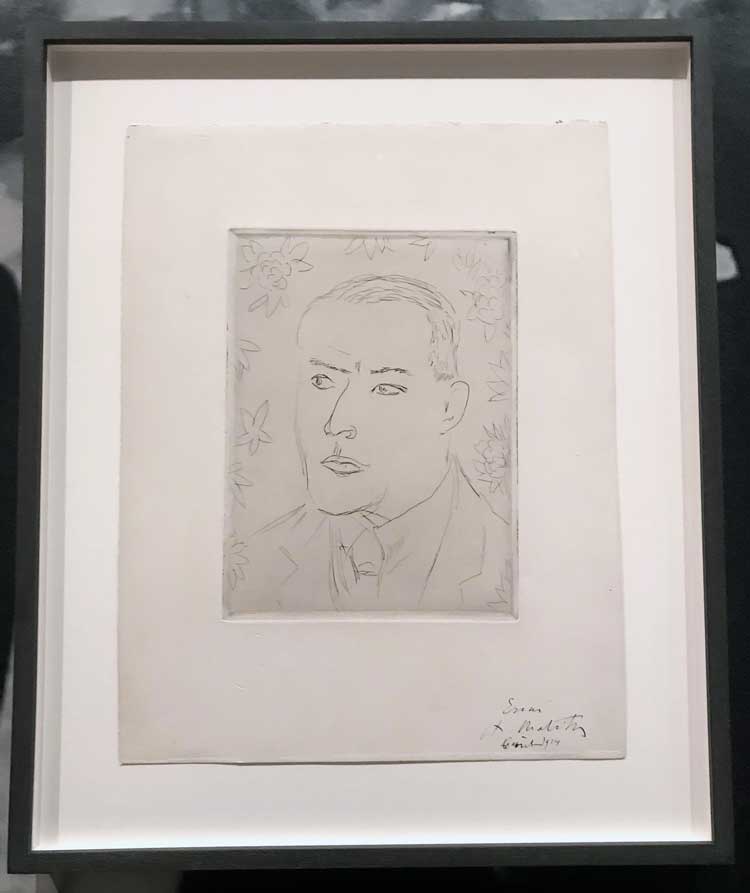

Henri Matisse, M.S. Prichard, 1914. Etching with chine collet, plate: 19.9 x 14.8cm; sheet: 32 x 25.2cm. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Stephen C. Clarke Fund. Photo: Marie Pohl.

The rather peculiar connection to a nightclub owner came through the British scholar Matthew Stewart Prichard. Over the years he had introduced Matisse to affluent collectors. In 1910, the two visited Masterpieces of Muhammadan Art together in Munich. The exhibition drastically impacted Matisse’s work. One could argue, it was here, viewing Islamic pattern, where Matisse’s colour found its magic touch. The influence is especially noticeable in The Red Studio. Studying Islamic art opened Matisse’s eyes to the concept of space. He discovered the flat surface, as opposed to the traditional western illusion of depth. The Australian art writer Robert Hughes phrases it best in his introduction to The Portable Matisse: “Everything from far to near is pressed with equal urgency against the eye. Matisse admired that, and wanted to transpose it into terms of pure colour. One of the results was The Red Studio.”

Prichard plays a pivotal role in the movie-worthy biography of this painting. During the first world war, the British scholar was taken to a prisoner-of-war-camp in Germany for four years. Matisse and his wife sent him food packages. At some point, after the war and after The Red Studio was sold to Tennant, the artist abruptly ended their relationship. An etching Matisse made of Prichard is on the nightclub photo wall.

A masterpiece in a nightclub? The Gargoyle Club wasn’t just any lousy nightclub. Located in the heart of London’s Soho, it was frequented by aristocrats, businessmen, celebrities and artists, including Francis Bacon and Lucian Freud. Names on the guest list on its opening night included Virginia Woolf, Noel Coward, Somerset Maugham and Nancy Cunard.

Postcard – The Gargoyle Club, Mirrored Mosaic Ballroom”, London, c1930s. Private collection, courtesy of Archives Henri Matisse. Installation view photo: Marie Pohl.

The interior design was spectacular. The show catalogue details “a fountain in the middle of the dance hall … A ballroom with mosaic walls of a thousand crystal mirrors … beneath a coffered ceiling of gold”.

I step closer to the photo wall and see The Red Studio on a postcard of the ballroom, in the far-right corner behind tables on which sit folded napkins. The yellow rocking chair – the only piece of furniture to escape the red cloak – pops out. The irony. A rocking chair in a nightclub.

Society’s outcasts often find refuge in nightclubs and bars, but the affairs are usually temporary. In 1938, Tennant wanted to sell The Red Studio. Honouring the contract, he offered it to Matisse first. The artist rejected it. Where it survived yet another world war and the notorious bombing attacks on London, is not quite clear. The wall text states that Tennant consigned it to the Redfern Gallery in Mayfair, London. The show catalogue says: “An exact timeline of The Red Studio’s travels over the next seven years cannot be plotted.” In 1945, it was sold to the Swiss-born gallerist Georges Frédéric Keller, who rescued the painting, and brought it to New York. And in the city of dreams the painting finally received its first good reviews.

The art critic Robert M Coates raved in the New Yorker about “an amazing mingling of the abstract and the representational, the flat patterned and the three dimensional, of tonal exuberance and formal restraint”.

When Keller put the painting up for sale in 1948, MoMA’s founding director, Alfred Hamilton Barr Jr, called an emergency meeting of the Committee of the Museum Collection. He told them: “Almost all the best Matisses of this period are now in Moscow. There is nothing like this picture in this country.”

Panneau Rouge – Atelier Interior – Artist’s Studio – and Studio was now The Red Studio, a name the Matisse family had been using for decades. Under this final title, the painting became a resident of MoMA’s permanent art collection.

Shchukin’s rejection was a blessing for modern art. In 1948, Joseph Stalin shut the doors of the bourgeoisie-infested Museum of Modern Western Art. In New York, The Red Studio influenced an entire generation of younger painters in the late 1940s and the 1950s.

“The idea of colour … the idea of the freedom of Matisse seemed to be a kind of freedom that seemed natural and open, something more sympathetic to the kind of American drive … to make more expansive, larger and more open paintings … Certainly painters like Rothko and Newman would be unthinkable without Matisse. And I think unthinkable without Matisse from the Museum of Modern Art,” says the American painter Frank Stella in the documentary Henri Matisse – Voyages.

The Window

I need a break. I haven’t visited The Red Studio yet, but I need a break. The curators set up a room behind The Studio gallery with chairs by a window facing East 54th Street. I sit down and lean back.

New York City itself is part of this show. It gave the vagabond painting its deserving recognition, and a home.

When Matisse travelled to New York, he told reporters, he could imagine no better place for a painter. “The New York light is exceptionally beautiful.” He explained to the poet Dorothy Dudley (in Matisse on Art by Matisse and Jack Flam, revised edition). “The atmosphere in New York is so dry, so crystalline, like no other.”

I recently met a young French painter. He told me, he is more of a “Matisse guy” as opposed to a “Picasso guy”. Picasso could draw like Michelangelo when he was 13 and invented cubism at 21. “Picasso was a genius when I was still in high school.” Matisse, on the other hand, was still struggling in his 30s and didn’t start making great works until later in life. He was 41, when he painted The Red Studio. “That’s reassuring for a guy like me.”

“We tend to think of Matisse as pretty, but there is a lot of edge to what he did.” The young French artist went on:. “Take the painting Dance. The figures are holding hands as they spin in a circle, except the two in the front. Their fingers can’t quite reach each other. It gives you the feeling that the circle could fall apart any minute. There’s always a glimpse of distress in Matisse.”

He described the exhibition as like “a Marvel movie with all the superheroes in the same room – the huge painting in the middle and everything else next to it”.

The Studio

The Red Studio is flanked on either side by three freestanding walls, each exhibiting a painting. The sculptures are perched in the middle of the room. A series of sketches parades along the back wall. You can walk back and forth between the original works and Matisse’s illustrations of them. That’s the idea.

A crowd of people is always huddling around The Red Studio. The size intrigues, large, but not too large. The box of crayons on the table catches my eye. Matisse didn’t paint the box Venetian red. He didn’t paint it white either. He marked the edges and left the rest blank. His crayons are lying on raw canvas. And he placed them at the forefront of the painting like a prompt: Welcome to my world of art.

Henri Matisse, Female Nude, 1907. Ceramic plate, tin-glazed earthenware, 24.8cm diameter. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. © 2022 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

The curators do the exact opposite by asking me to look at real pieces. But their guidance also inspires you to ponder and cherish every detail, such as the hand-painted ceramic plate Female Nude (1907), which is displayed in a glass case. It was made in collaboration with the ceramist André Metthey. From 1907-1908, Matisse and Metthey fabricated about 40 ceramic pieces. The plate shows a female nude in a curled position with a striking facial expression. What do her eyes and mouth tell me? Is she scared? She is covering her ears with her hands.

In The Red Studio, the plate is not as elaborated, but the concave feeling the figure evokes, remains. Matisse set the ceramic in the front row, next to the box of crayons. Behind them, an ochre-yellow female hides in nasturtium tendrils cascading out of a long-necked bottle. The plant tenderly embraces the woman like a secret too precious to reveal.

The original terracotta figure has lost her head and forearms, which I find fittingly mysterious. Upright Nude with Arched Back (1906-07) is a small statuette from Matisse’s fauve period. Her left knee rests on a base, her arms sensually stretched out above her head in a mannered, erotic pose modelled after a nude photograph Matisse took from a magazine. The statuette was among several recently discovered in the belongings of Jean Matisse, the artist’s elder son.

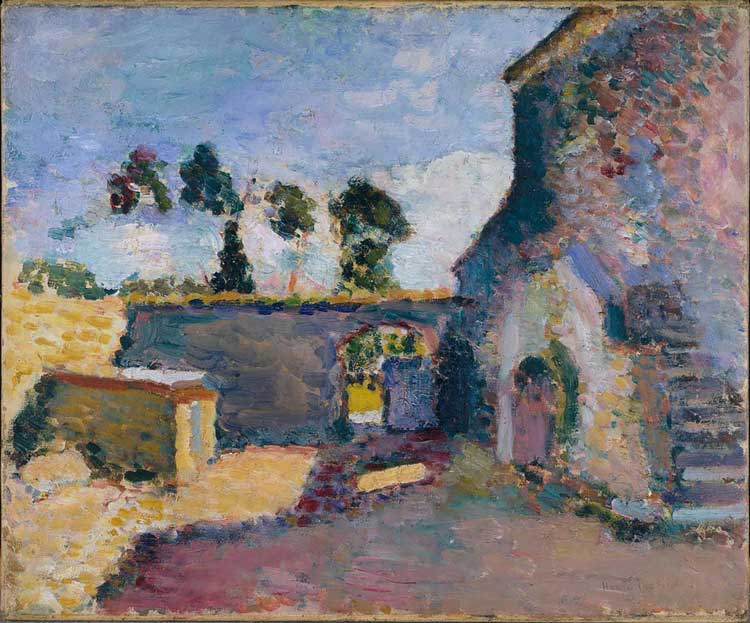

Henri Matisse, Corsica: The Old Mill. 1898. Oil on canvas, 38.5 × 46cm. Wallraf-Richartz Museum & Fondation Corboud, Cologne.

Corsica, the Old Mill (1898) is the earliest work in Matisse’s studio interior. He painted the lovely courtyard of the stone building in Ajaccio, Corsica, where he and his wife Amélie spent the first months after their wedding. One can almost hear cicadas chirping in the trees. The artist described the ocean in a letter to a friend, as “blue, blue, so blue you could eat it”. His own colours are tender, modest, and fragile. Other paintings from the same year, The Olive Tree, or Village in Brittany, indicate a similar shyness of the young painter, still searching for his own voice.

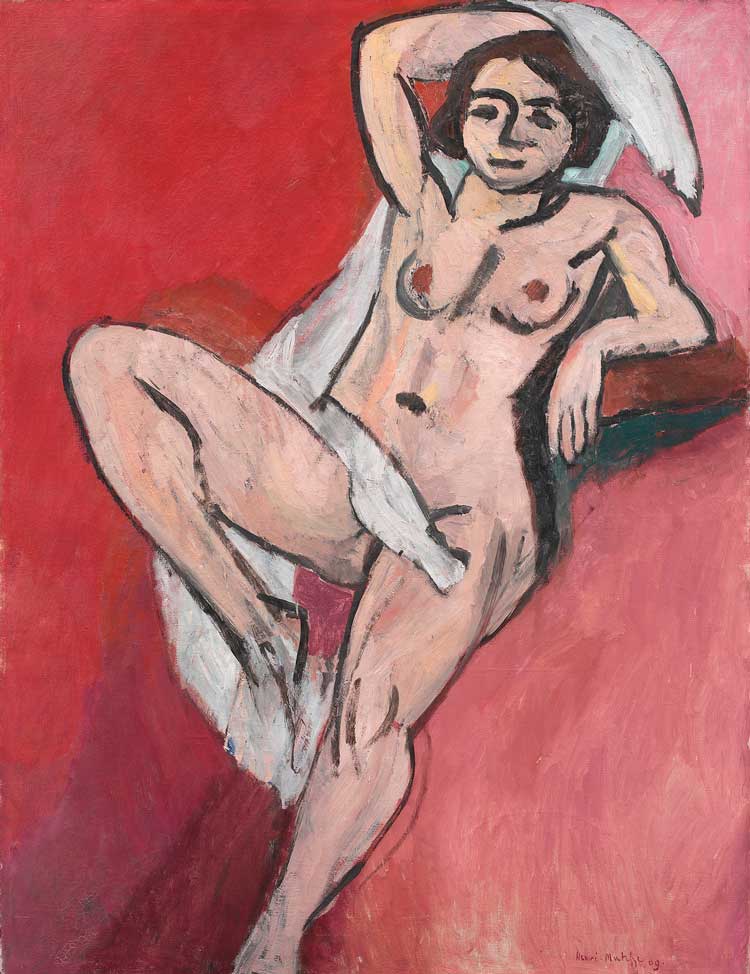

Henri Matisse, Nude With White Scarf. 1909. Oil on canvas, 116.5 x 89cm. J. Rump Collection. SMK – The National Gallery of Denmark, Copenhagen.

The two ladies I saw earlier are viewing Nude with White Scarf (1909). The nude leans leisurely against a pinkish-red background, a white scarf around her body, one arm raised, the other resting. The black line next to her calf suggests revisions by the artist. Interestingly, Matisse did not cover up the line. He left it there. Maybe to add a sense of movement to her leg.

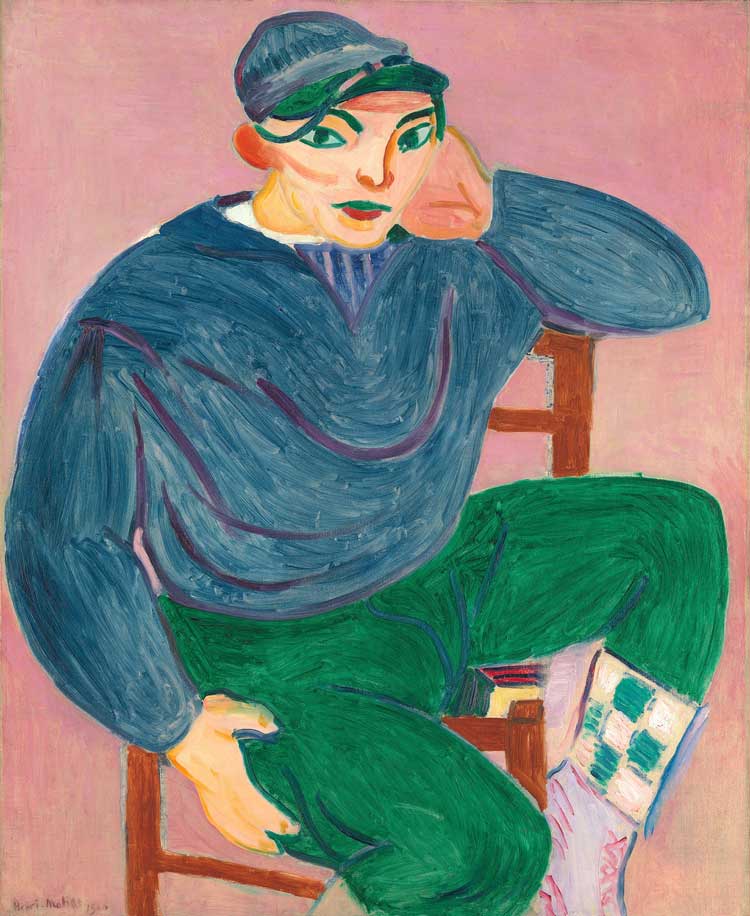

The Italian lady calls it “an amused yet slightly disappointed after-sex painting”. Then she walks over to Young Sailor II (1906).

Henri Matisse, Young Sailor II, 1906. Oil on canvas, 101.3 × 82.9cm. Jacques and Natasha Gelman Collection, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

The rendition gets lost in The Red Studio due its small size. In reality, the painting is quite large and powerful. The artist met his model, an 18-year-old fisherman, in Collioure, a town in southern France, where he painted two versions of the portrait.

The ladies are eagerly discussing the sailor.

“He’s got red ears,” the signora says.

“It’s all about the green. It’s the same green in the eyes, the moustache, the hat and the pants,” the other lady comments.

“I like the way he grips his pants, and how he’s looking straight at me. This guy can capture any woman’s heart.”

“I don’t understand how you can like French men. They can’t be trusted,” her companion answers.

Matisse arranged his bronze sculptures Jeannette IV (1911) and Decorative Figure (1908) on two stools in the back of The Red Studio, facing each other as if engaged in a chatty conversation. They are oblivious to the unidentifiable “thing” next to them. Is that a light switch at the very edge of the painting?

The New Yorker dedicated an entire article to this question. Patricia Marx tried to decipher, what she calls, the “thingamabob”. It’s not a light switch, Marx clarified, because light switches in 1911 were push buttons. None of the curators, or the researchers at the Archives Henri Matisse, not even the artist’s great-grandchildren know what the strange rectangle resembles. Marx cites the art critic David Apatoff, who graciously remarked: “Matisse… rejected the traditional realism… here we are a century later, and scholars are still trying to drag him back, reconnecting his decorations with their subject matter.”

Meanwhile, the two real sculptures sit grace the room on pedestals. Jeannette IV shows off her long nose and Decorative Figure smiles as her hand gently covers (or plays with?) her crotch.

In 1899, Matisse bought a small Paul Cézanne, Bathers, which became his talisman. In 1907, he painted his own version. And in 1911 he painted his painting into his studio painting. Matisse: the ultimate painter of paintings. People are gathered around the original. Bathers (1907) hangs beside the famous Le Luxe II (1907). Few notice the rarely exhibited Cyclamen (1911) among this group.

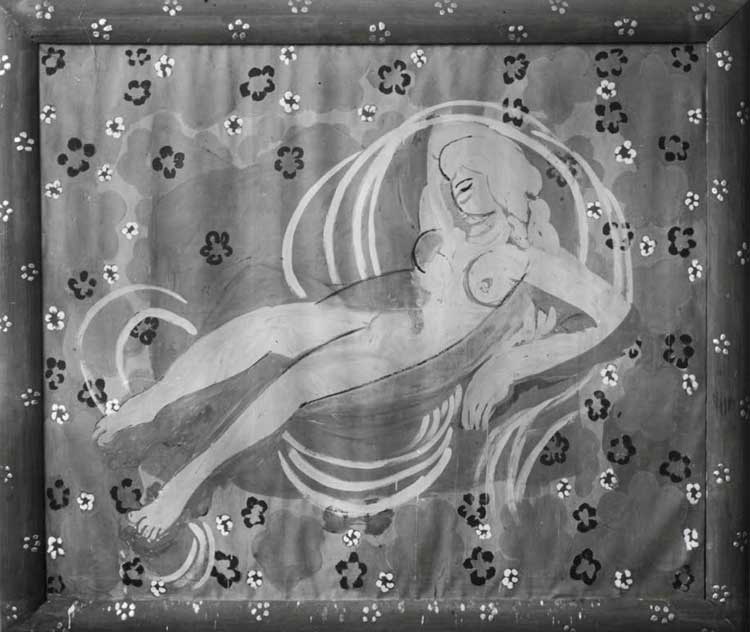

The curators were able to bring together all the artworks from The Red Studio except for one. I call it the Marilyn Monroe painting. It’s pink. It’s sexy. She’s blonde. It’s Marilyn singing Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend. The Large Nude (1911), a reclining nude against a background of five-petalled flowers, is the largest painting featured in The Red Studio. In a letter to his wife, Matisse wrote it “could be called the night”, referencing Michelangelo’s sculpture Night.

Photograph of Large Nude 1911, by Eugene Durat, 1916. Archives Henri Matisse. Distemper on canvas. Dimensions unknown. Estimated size 190 x 240cm. 1911-1954 With the Artist. 1954-?, 1956 destroyed by Jean Matisse. Installation view photo: Marie Pohl.

The Large Nude was never exhibited or sold. Matisse considered it unfinished and ordered that it be destroyed after his death. The curators provide a fantastic alternative: five studies for Large Nude.

The first is jotted down quickly with coloured ink, like a note, not to forget the idea. The next three are done in pencil, the last with pastel and graphite. Some have flowered backgrounds, others don’t, their legs and hands vary in positions. It is wonderful to witness the experimenting, to observe Matisse trying this and that, and to understand that finding the right form is a process. Sometimes for ever incomplete.

“One would die to know what was on Rimbaud’s mind, when he wrote The Drunken Boat, or on Mozart’s when he composed his symphony Jupiter. We’d love to know the secret process guiding the creator through his perilous adventures. Thankfully, what is impossible to know for poetry or music is not the case of painting. To know what’s going through a painter's mind, one just needs to look at his hands …” These lines open Henri-Georges Clouzout’s movie The Mystery of Picasso (1956), in which he shows Picasso drawing, altering, adding, until the painter reaches a finite image, or dismisses the piece altogether. There is no such documentary of Matisse at work, but new conservation technologies offer a glimpse into the stages of creating The Red Studio.

A six-minute film shares the most recent discoveries of infrared-sensitive cameras, X-rays and other fascinating technologies. These reveal that the charcoal sketches of the objects and furniture were done without any major changes. Matisse kept all his underdrawings, except for a horizontal line inside the curtained window. Maybe, for a moment Matisse considered painting an open window? The Red Studio has no window with a view. There is no exit. The eyes cannot escape the red intensity unless they gaze at the art. So: the artworks become the windows in this painting.

Are they windows or are they stars? The traces of the furniture remind me of star constellations. Matisse painted his alternate art-universe, which needs nothing but itself, and offers an alternate reality far, far away from our real and troubled world.

When conservators took the painting out of the frame, they found pink, blue and yellow paint underneath the Venetian red coating. Their specialised cameras proved that the walls were indeed cobalt-blue panels, the floors madder-lake pink and the furniture ochre yellow. Even without a camera, standing right in front of it, I notice the vigorous brushwork. Matisse must have laid down the red colour in an instant. A few brush hairs are still embedded in the paint, as seen between the legs of the left stool.

He did a similar thing with an earlier work. The Dessert: Harmony in Red (1908) was originally called Harmony in Blue and painted in a harmony of blue. After Shchukin bought it, Matisse took it back and repainted it a uniform crimson red. “It is forces that I am concerned with,” the artist said, “and a balance of forces.”

Shchukin loved Harmony in Red. “I like the red room enormously,” he wrote to Matisse. Harmony in Red has a window with a view on to green grass, trees and a blue sky. The crimson is brighter, more joyful and decorative than the slightly solemn shade of the Venetian red. It’s one the oldest known colours, used in cave paintings during the Palaeolithic era. The name originated in the mid-1700s in the Veneto region of Italy.

“‘You are looking for the red wall,’ Matisse said to a visitor who came to his studio shortly after this painting was completed. ‘This wall does not exist at all! … Where I got the colour red – to be sure, I do not know… I find that all these things, flowers, furniture, the chest of drawers, only become what they are to me when I see them together with the colour red.’” (Former chief curator of MoMA, John Elderfield quotes the artist in his book Henri Matisse: Masterworks from The Museum of Modern Art.)

The last oil painting Matisse made before dedicating himself solely to paper cut-outs pays homage to his Red Studio. Large Red Interior (1948) marks the final painting of the exhibition. The studio-interior has no window either, but it feels less intense, less trapping. It’s probably the vibrant yellow lemons on the table.

Picasso said about his friend: “Matisse has the sun in his belly.”

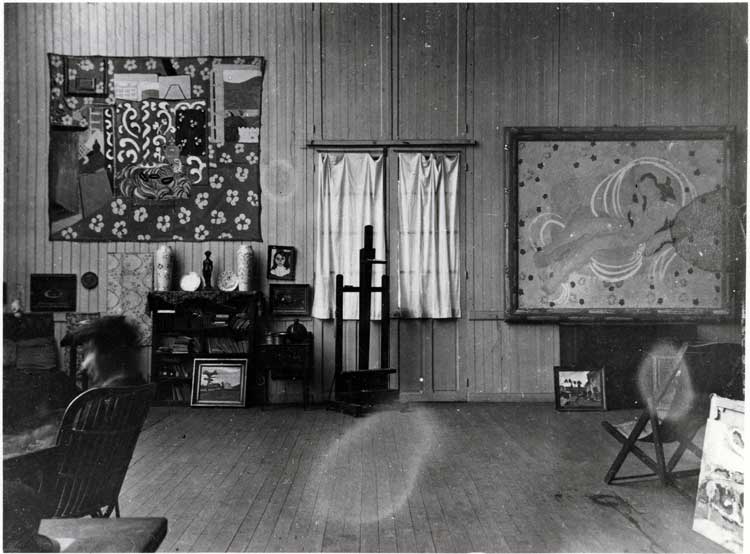

Photograph of the interior of Matisse’s studio in Issy-les-Moulineaux. October / November 1911. Private collection, courtesy Archives Henri Matisse. © 2022 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

As I exit, I am faced with a photograph showing the interior of Matisse’s studio. Just as in the painting, the little Corsica, Old Mill is placed on the floor and, just as in the painting, there is a curtained window. In the photograph, light floods the room. There is no light flooding the Red Studio, only a red sky, enclosing and everlasting like an artist’s eternal struggle to make his works shine – like stars.

• Matisse: The Red Studio will be at the National Gallery of Denmark (Statens Museum for Kunst; SMK), Copenhagen, from 13 October 2022 to 26 February 2023.