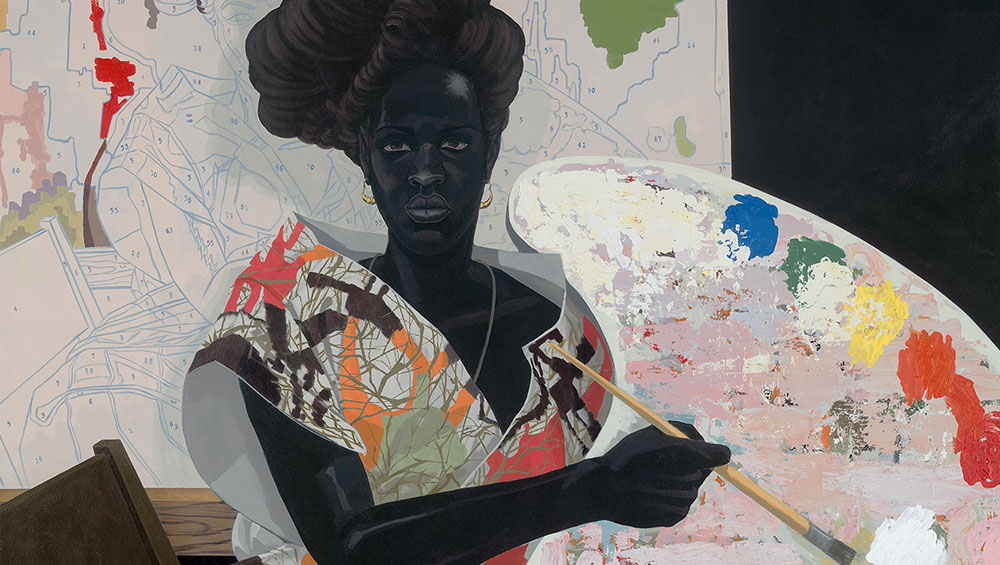

Kerry James Marshall, Untitled, 2009 (detail). Acrylic on PVC panel, 155.3 x 185.1. Yale University Art Gallery, Purchased with the Janet and Simeon Braguin Fund and a gift from Jacqueline L. Bradley, B.A. 1979. © Kerry James Marshall.

Royal Academy of Arts, London

20 September 2025 – 18 January 2026

by JOE LLOYD

It takes us nine rooms into The Histories,the Royal Academy’s mammoth exhibition of the American painter Kerry James Marshall, to come across a series of history paintings that a 19th-century salon artist would recognise in style – though not in subject matter. Africa Revisited, created for this show, is a sequence of scenes from African history. There is the assassination of Shaka Zulu by his two brothers in 1828, and the kidnapping of the then 11-year-old Olaudah Equiano and his sister from their Igbo village. A stupendous triptych shows African slave traders riding out with captives and returning laden with booty. Marshall’s command of movement and figuration, his attention to detail, his lavish colours: these are bravura works of art, the sort that you could imagine an audience queuing up outside the Paris Salon to see. They show Marshall, who will be 70 in October, at his prime.

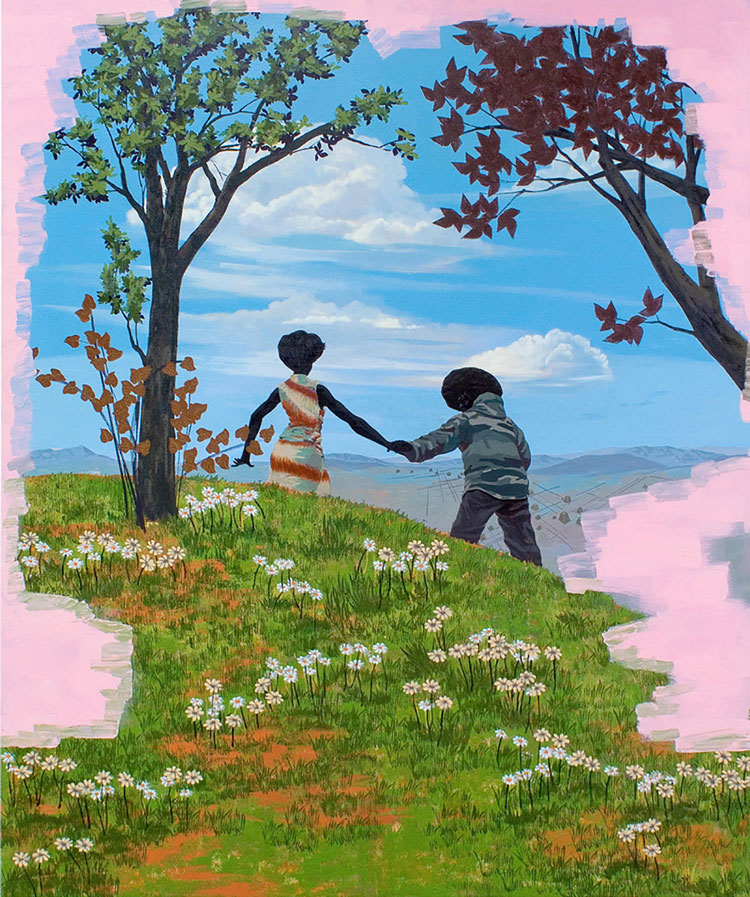

Kerry James Marshall, Vignette #13, 2008. Acrylic on PVC panel, 182.9 x 152.4 cm. Susan Manilow Collection. © Kerry James Marshall. Image courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Marshall was born in Birmingham, Alabama. He decided to become an artist in kindergarten after a teacher showed him a scrapbook of cutout and collaged images. At eight, and now living in Los Angeles, he stood in awe beneath the Italian Renaissance paintings and Ivorian sculptures of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Art school was inevitable. Marshall’s childhood and studies occurred during a febrile time in American racial politics, from the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing in Birmingham in 1963 to the Watts riots in 1965 over the Los Angeles Police Department’s racist policies. Setting out as a practising artist, he was well aware of his country’s extreme racial inequality, and the paucity of representations of African Americans in museum collections.

Kerry James Marshall, Untitled (Blanket Couple), 2014. Acrylic on PVC panel, in artist's frame, 150.2 x 242.5 cm. Fredriksen Family Art Collection. © Kerry James Marshall. Image courtesy of the artist and David Zwirner, London.

“So,” writes curator Mark Godfrey, “Marshall set out on his mission, restated several times since then, to glean knowledge in order to make masterful, authoritative paintings that unequivocally centred Black subjects.” As a student he participated in performances and sold small-style collages. But he soon determined that figurative painting, against all the biases of the time, would be his metier. He began with portraiture. Marshall’s most striking early works feature a grinning man missing one tooth, based on racist stereotypes. We first meet this avatar in the tiny A Portrait of the Artist as a Shadow of His Former Self (1980), where his black skin and dark clothing barely contrast with the dusky background. Marshall had recently read Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, and in these works overtly references that rollicking novel’s conceit about black invisibility. Setting a standard that has remained throughout Marshall’s career, the character’s skin is blacker than any natural tone (“If you say black,” Marshall has said, “you could see black”). By contrast, his white eyes, teeth and shirt gleam like floating objects. Marshall used egg tempera, a medium commonly associated with the brightly coloured frescos of the early Renaissance. Through this, he announced a challenge to the absences in western art history.

Kerry James Marshall, De Style, 1993. Acrylic and collage on canvas, 264.2 x 309.9 cm. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Purchased with funds provided by Ruth and Jacob Bloom. © Kerry James Marshall. Photo: © Museum Associates / LACMA.

Marshall’s ambitions grew in the 1990s. He started painting scenes from real and imagined black lives: a woman about to plunge into a pool, lovers slow dancing at a house party, residents gardening in their housing projects, a barber moulding hair into fantastical shapes. The latter, De Style (1993), is a cornucopia of art historical reference: Rembrandt poses, Manet mirrors, De Stijl grids of red and white. Yet it is also specific to the moment. A calendar shows April 1991, a month after the brutal beating of Rodney King by officers from the LAPD. The barber and his customers stare out of the canvas with smouldering defiance. Marshall wrote to his friend and collaborator Arthur Jafa in 1994: “I’ve always wanted to be a history painter on a grand scale like Giotto and Géricault.” But here he showed not the action but the response that this elicits. It is the history painting equivalent of history from below.

History painting was once regarded as the most prestigious form of art. The impressionists and modernists rejected it as old hat, and history painting now seems itself consigned to history. When contemporary artists engage with it, it is often to make a comment on the genre itself. Marshall was a pioneer of this tendency, which has since become more commonplace. His works often seek to redress the absence of black lives and stories in western painting. But Marshall’s style is so idiosyncratic, and his subjects so exploratory, that his practice transcends mere commentary.

-NEW-FILE.jpg)

Kerry James Marshall, Knowledge and Wonder, 1995. Oil on canvas, 294.6 x 698.5 cm. City of Chicago Public Art Program and the Chicago Public Library, Legler Regional Library © Kerry James Marshall. Photo: Patrick L. Pyszka, City of Chicago.

For one, he does not restrict himself to imitating this declined genre. He often uses collaged elements, whether photographs or texts. Some works have signatures in golden glitter, a choice that occasionally renders his work a little kitsch. Marshall is also not wedded to verisimilitude. A series of watery early 90s works about the Middle Passage feel more like symbolist dreamscapes than representations of individual occurrences. His figurative scenes are intercepted by floating banners conveying messages, globules of abstract colour, lines drawings. In Past Times (1997) notes and lyrics float out from the radio, like the golden words of some Sienese Annunciations. This echo is more specific in the excellent Souvenir series (1998), here given pride of place, which depict a worn-down looking black archangel in domestic settings, surrounded by mementos of fallen civil rights and cultural heroes.

Kerry James Marshall, School of Beauty, School of Culture, 2012. Acrylic and glitter on unstretched canvas, 274.3 x 401.3 cm. Collection of the Birmingham Museum of Art, Alabama; Museum purchase with funds provided by Elizabeth (Bibby) Smith, the Collectors Circle for Contemporary Art, Jane Comer, the Sankofa Society, and general acquisition funds, 2012.57. © Kerry James Marshall. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York. Photo: Sean Pathasema.

Throughout it all, Marshall’s engagement with both western and African art history is capacious. It seldom overwhelms the paintings’ qualities as individual works. It can be subtle, such as with his portrait of abolitionist David Walker in the style of Ingres (2009), or a depiction of slave rebellion leader Nat Turner (2011) with the head of his master that evokes the countless baroque renditions of Judith and Holofernes. At other times, it is more overt. Gulf Stream (2003) shares most of a name and a composition with Winslow Homer’s The Gulf Stream (1899). School of Beauty, School of Culture (2012), a companion to De Style set in a women’s hairdresser, features the head of the Disney Sleeping Beauty in place of the skull in Holbein’s Ambassadors (1533). While Holbein was summoning a memento mori, Marshall appears to be highlighting the pre-eminence of white beauty standards. But while two toddlers assail this apparition, the adults around them ignore it. Have they grown out of caring about such prejudiced ideas?

The reference to Disney is indicative of Marshall’s magpie-like attitude to popular culture. He populates his scenes with photographs, news clippings and LP covers. His hair salon is decorated with a poster for Chris Ofili’s 2010 Tate Britain retrospective. For all the monumental myth-making of Marshall’s paintings, he also has an interest in the perishable ephemera of the here and now. These are not simply history paintings but living history paintings, richly suggestive of the lives lived outside the moment translated on to canvas. At their best they arouse the similar awe to their illustrious predecessors.