Hormazd Narielwalla. Photo: Denis Laner.

by ANNA McNAY

Hormazd Narielwalla (b1979, India) studied fashion, at home and in the UK. During his master’s course, he began working with paper patterns to create collages – sometimes figurative, sometimes abstract – sometimes even sculptural. He has since gone on to build his practice around pattern, has won numerous awards and commissions, and has produced 10 limited-edition artist’s books. The latest of these, Diamond Dolls (published this month), created in an edition of 300, takes as its muse David Bowie. Growing up as a young gay man in India, Narielwalla was hugely inspired by Bowie’s gender fluidity and confidence and felt he was an icon he could emulate. In his 36 collages for the book, Narielwalla uses a variety of specialist textile patterns to capture Bowie’s essence, or living spirit, and create outfits he might have worn, but never did (Narielwalla is keen to emphasise that he creates rather than copies – he is an artist not an illustrator).

Narielwalla spoke to Studio International via Zoom during the run-up to the launch of Diamond Dolls.

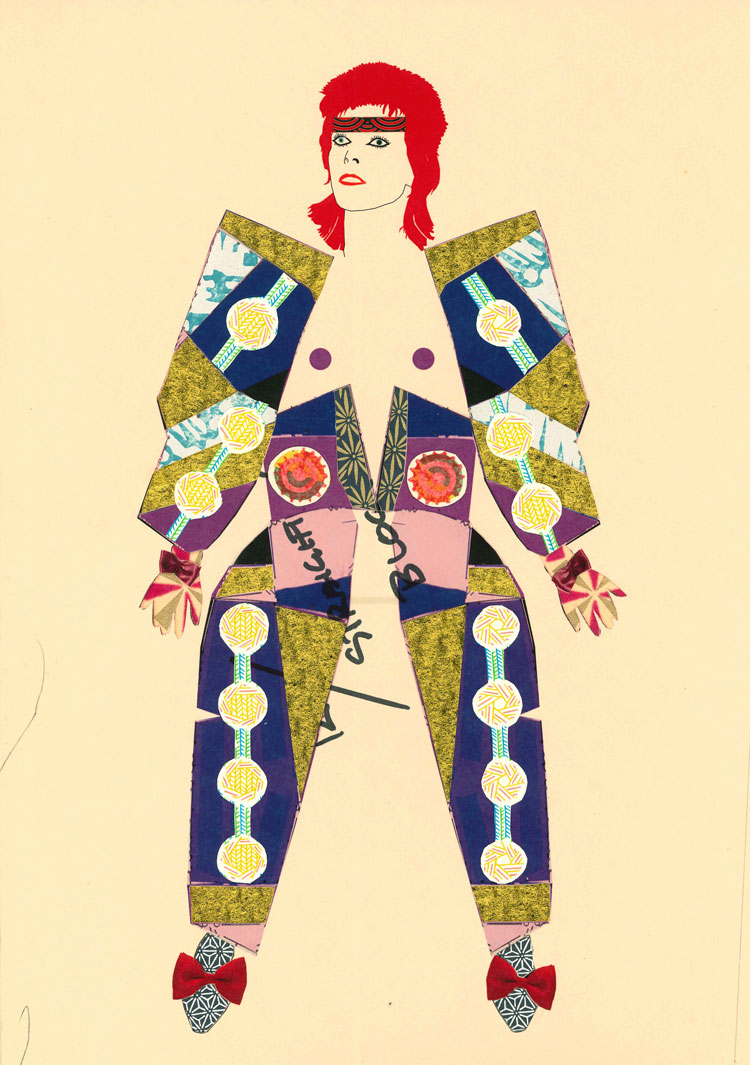

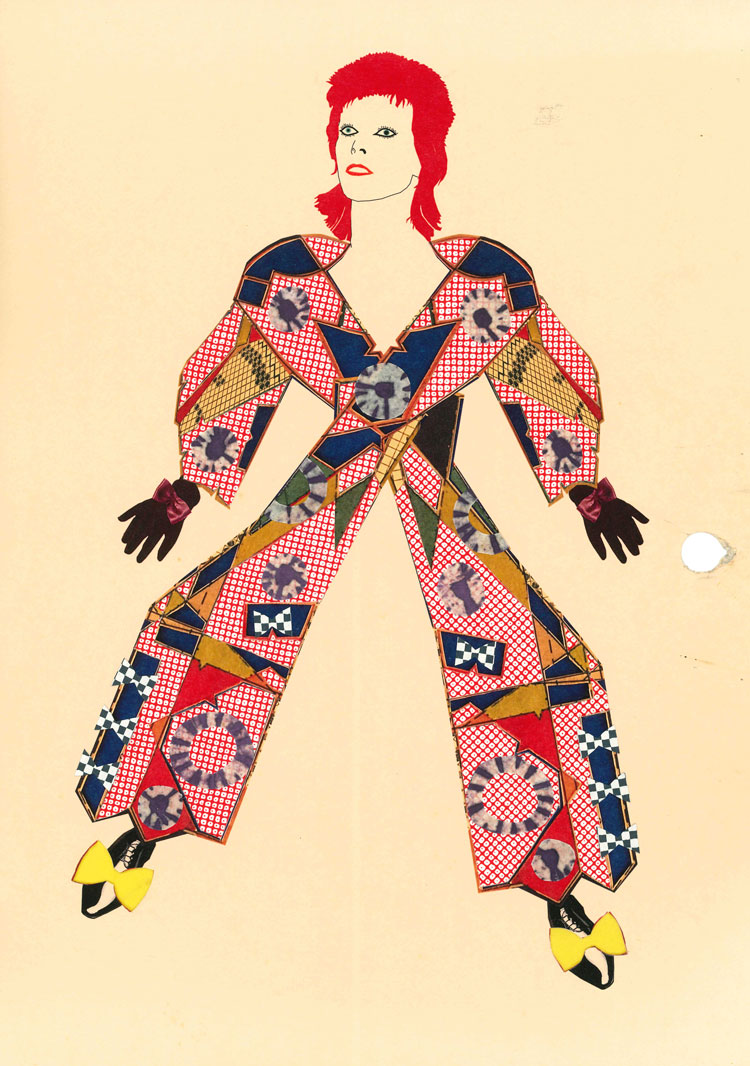

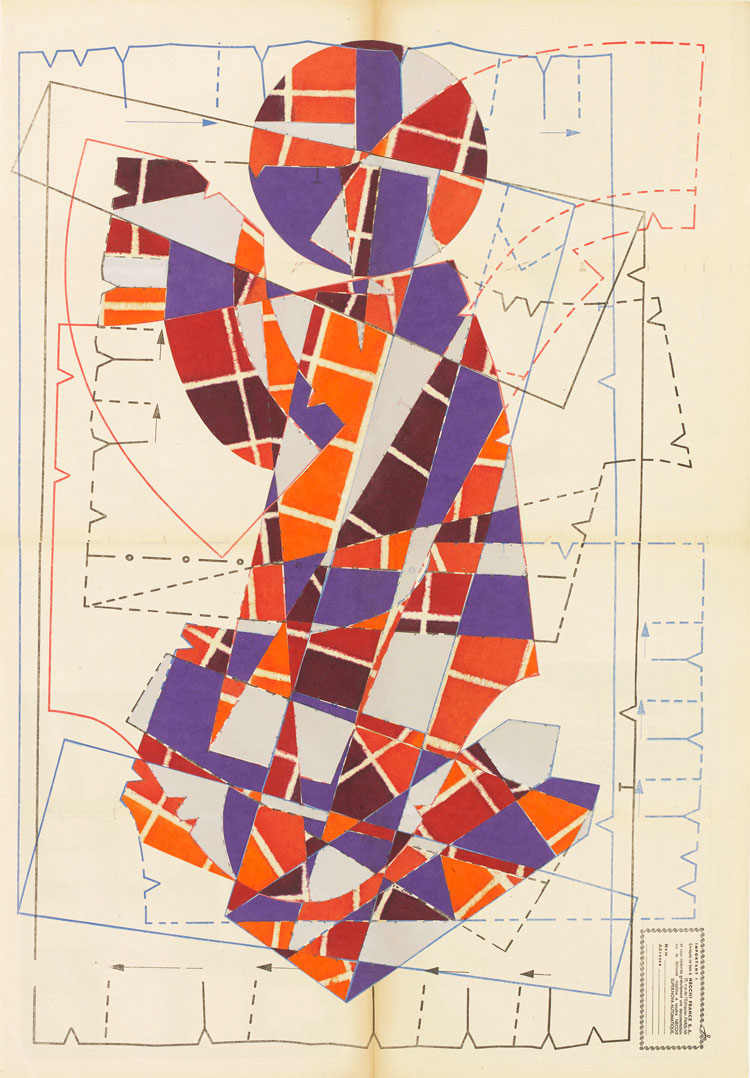

Hormazd Narielwalla. Diamond Dolls no. 7, 2021. Mixed media on vintage bespoke tailoring pattern, paper size 42 x 29.7 cm. Copyright Hormazd Narielwalla. Image courtesy Eagle Gallery / EMH Arts, London.

Anna McNay: Diamond Dolls is a limited-edition artist’s book comprising your trademark collaged figures, made using textile patterns, here celebrating the gender-fluid persona of David Bowie. It was formally launched on 15 July, alongside an exhibition.

Hormazd Narielwalla: That’s right. The book and the exhibition go together: I’m showing the original collages from the book. And just to clarify: the collages are made from paper sewing patterns, so they are for textiles, but not cloth-based. Because of my background in fashion, I try to make the paper look like textile. Sometimes I do use a bookmaker’s cloth, which is fused at the back, so it really cuts like paper, but the colour is different, because cloth and paper absorb colour differently.

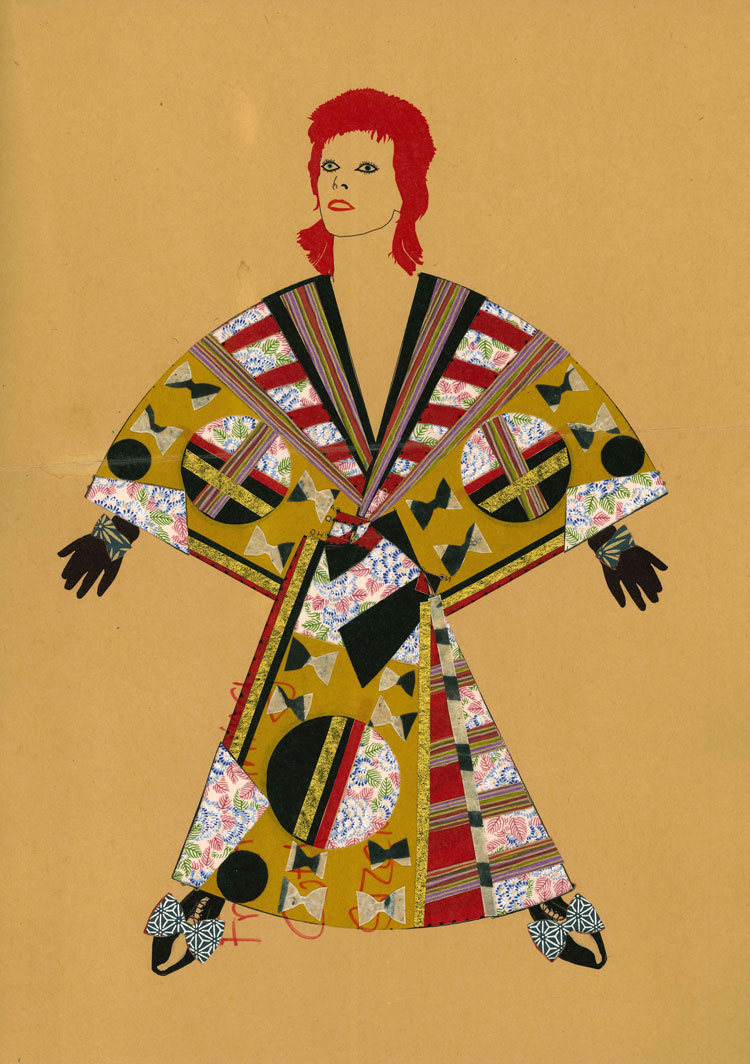

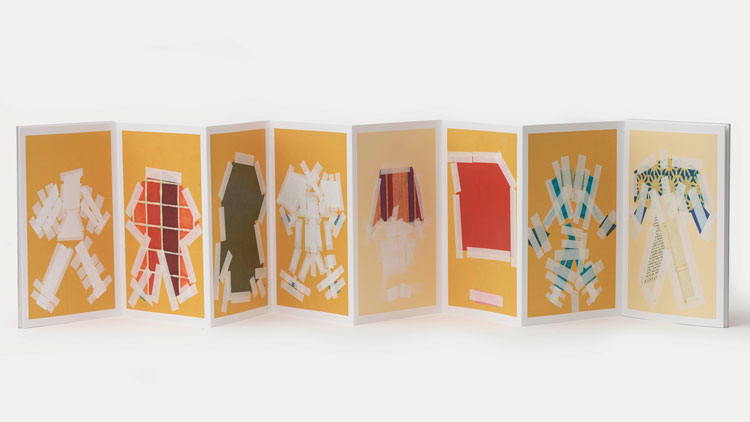

Hormazd Narielwalla. Diamond Dolls, 2021. Copyright Hormazd Narielwalla, image courtesy Eagle Gallery / EMH Arts, London.

AMc: Maybe we can come back to specifically what paper patterns you have used in a minute, but, first, can you tell me what Bowie means to you, why you have chosen to create this whole work around him, and why now? I know he was significant for you when you were growing up in India as a young gay man in the 80s and 90s.

HN: It was during the pandemic when we had a lot of time on our hands. I speak for myself, but I kept thinking about the past, and I started thinking about my years growing up in India. India was quite shut off until the 90s. We did not have a constant influx of western culture. It did come through, but not in the way we are used to in Britain today, for instance, where we have access to things from Australia, America and Europe. In India, at that time, it was still very restricted. Then MTV came out, it started broadcasting videos from the 70s, and Bowie just popped up on my screen. It was one of those moments you never forget. I was looking at this man, but he also looked a bit like an alien, to me, at least, with his red hair and green eyes, and he embraced this very different kind of masculinity. He was very fluid with his gender, but also clearly a man, and so the idea he was channelling was of a very confident person, comfortable with who he was, and this made me feel it was something I could emulate.

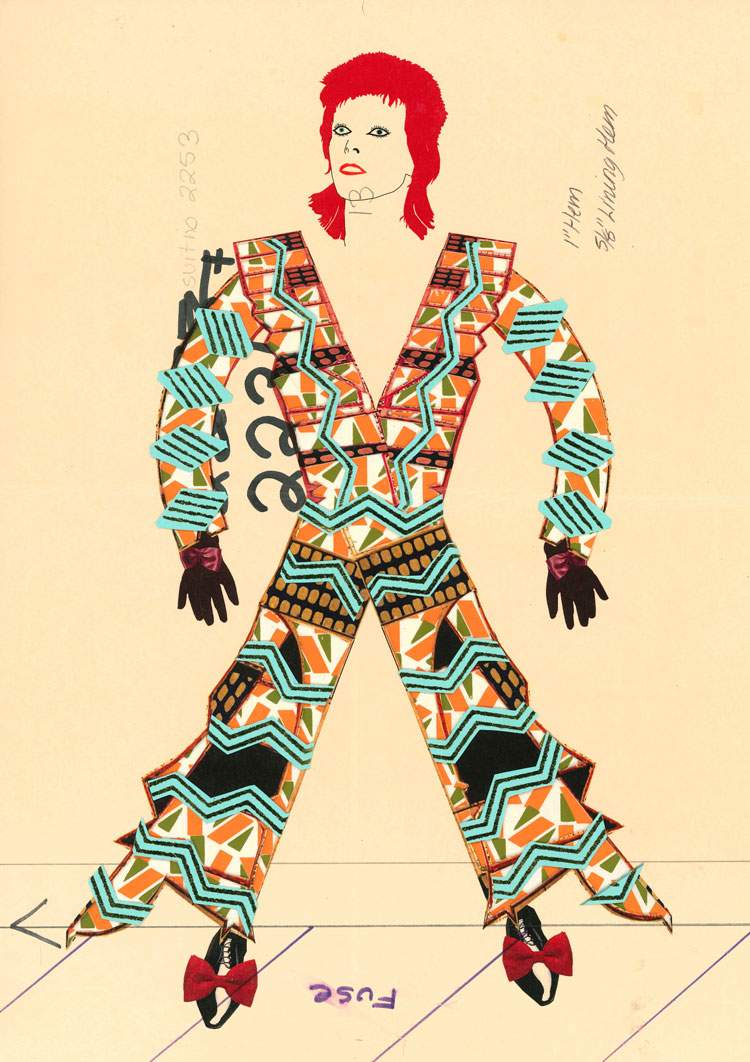

Hormazd Narielwalla. Diamond Dolls no. 11, 2021. Mixed media on vintage bespoke tailoring pattern, paper size 42 x 29.7 cm. Copyright Hormazd Narielwalla. Image courtesy Eagle Gallery / EMH Arts, London.

There was, of course, also Freddie Mercury. He was Zoroastrian, as am I, so we were encouraged to look to him, but just not to be influenced by his overtly gay side. I think, when you’re growing up and being told that being gay is not a good thing, you reject Freddie Mercury pretty quickly, because he is so camp, and he really put his sexuality out there. With Bowie, however, it was quite ambiguous. He could just be seen as creative or eccentric. He could get away with being feminine or camp, and I think that was the initial attraction.

But, also during the pandemic, I was thinking a lot about legacy, and what we leave behind. As the work progressed, and the book was made, in some sense it became less about Bowie the man and more about his spirit, the idea that Bowie has not died. True, he’s physically not here, but Bowie, the god, is still with us. That’s what I was trying to say with this project. During the pandemic we all questioned our mortality because we were being told we were all going to get the virus and die. Of course, that’s not what happened, but I did question my mortality, and what I want to leave behind as an artist.

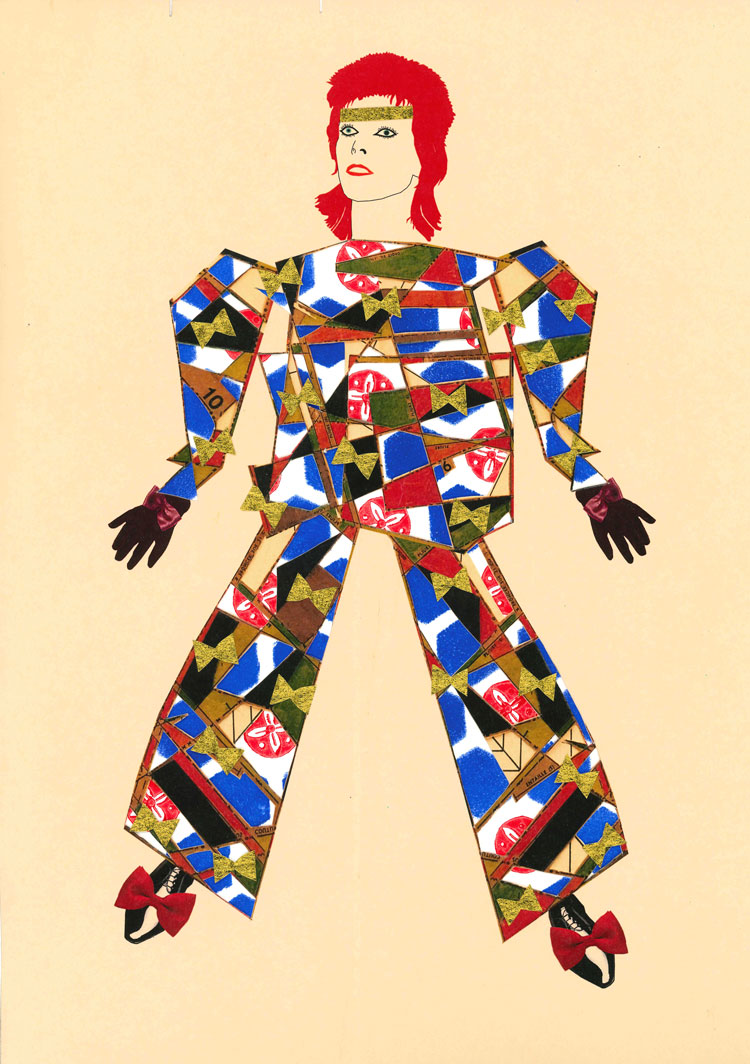

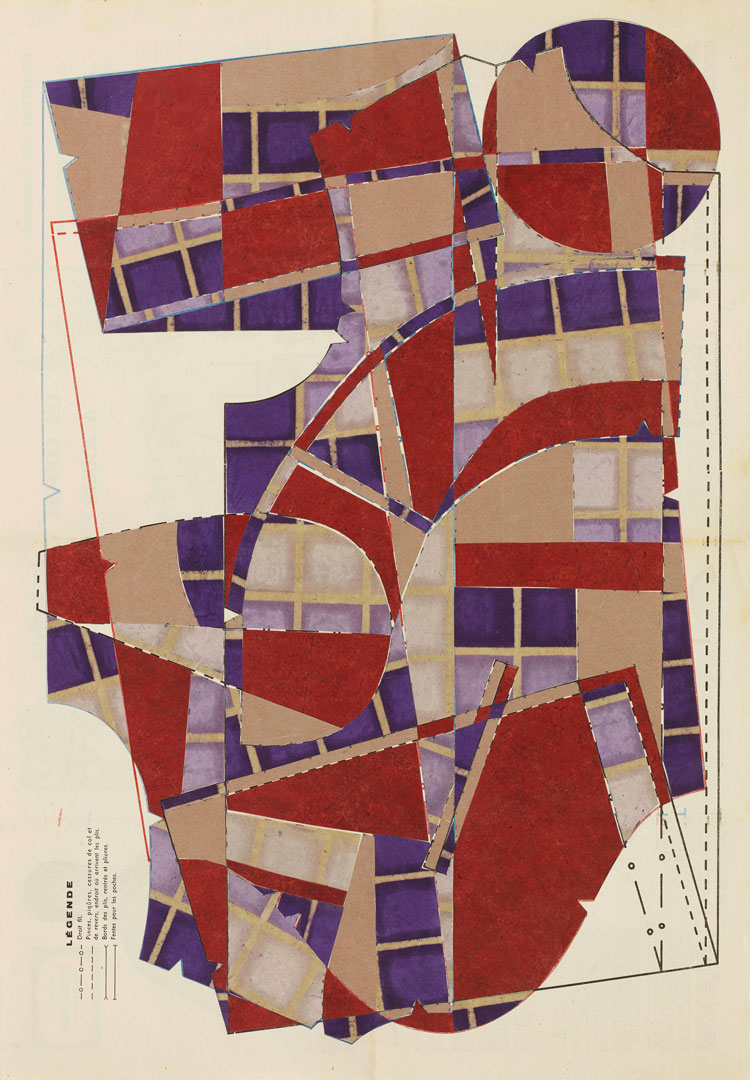

Hormazd Narielwalla. Diamond Dolls no. 14, 2021. Mixed media on vintage bespoke tailoring pattern, paper size 42 x 29.7 cm. Copyright Hormazd Narielwalla. Image courtesy Eagle Gallery / EMH Arts, London.

AMc: You say Bowie is not dead. Do you think he still carries that same message of hope for young people today, as he did for you, or are there other celebrities and a much more open culture?

HN: I think he still does, definitely. I mean, there are a few people: Frida Kahlo, Picasso, Princess Diana … These are people who have had such an impact on popular culture. They are not dead. They are never going to die. The Madonna is still a significant icon 2,000 years on, and, whether you are religious or not, you are confronted with the Madonna wherever you go. There are people out there who have left their mark and their legacy.

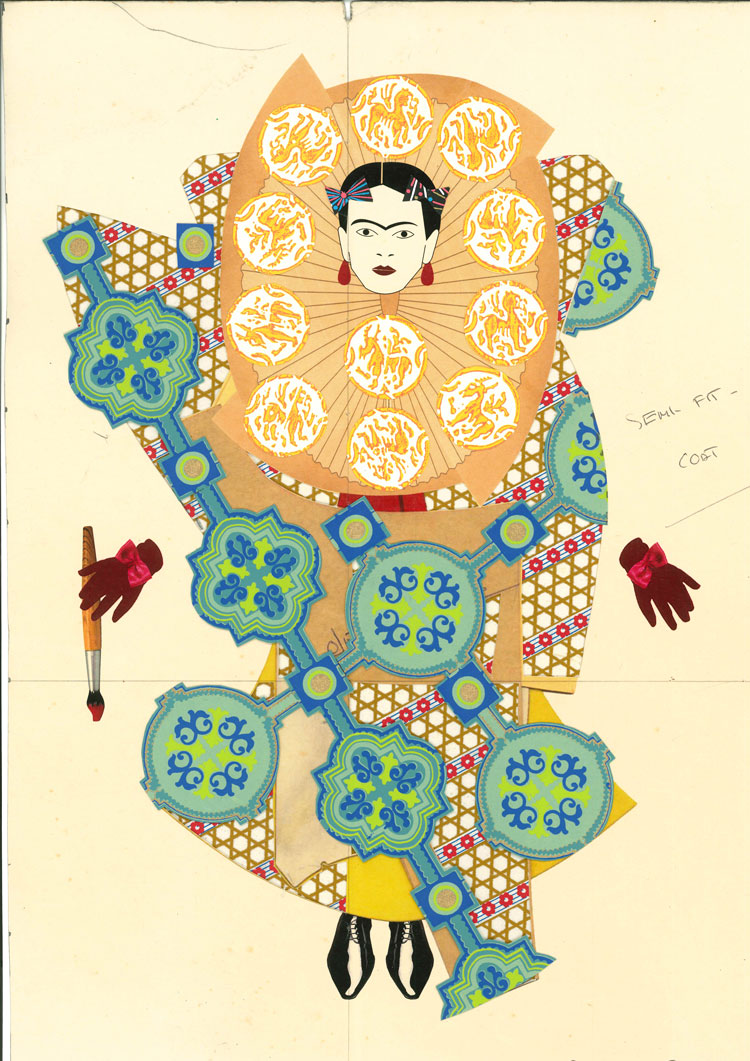

Hormazd Narielwalla. The Queen series - Frida Korea, 2021. Paper collage cut out and print on tailoring pattern, 42 x 29.7 cm. Copyright Hormazd Narielwalla, courtesy of Emma Hill Eagle Gallery.

AMc: It is interesting that you put Frida Kahlo first in that list because you were invited to make some prints of her when the V&A held its exhibition, Frida Kahlo: Making Her Self Up, in 2018.

HN: That’s right. I have had a strong fascination with Kahlo for a few years now. When I was starting to do fashion, I based an entire collection on her, and I have had a few similarities in my personal life, as well. When I was younger, I had a very bad back injury and was immobilised for about six months, and all I could do was draw. That’s when I realised that I wanted to be a fashion designer. When I recovered, I had a sit-down with my family and convinced them to allow me to do fashion in India, and then I started working as a stylist, before I came here to the UK to study fashion further. My injury was not as traumatic as Kahlo’s, but it was during that period that I picked up my sketchbook and pencil and began making fashion drawings. So, later, I made a whole series on her, and the V&A saw it and commissioned three prints from the series, but also a new one for itself. It made limited editions, and all of them, including two originals, are now part of its permanent collection.

Hormazd Narielwalla. Diamond Dolls no. 25, 2021. Mixed media on vintage bespoke tailoring pattern, paper size 42 x 29.7 cm. Copyright Hormazd Narielwalla. Image courtesy Eagle Gallery / EMH Arts, London.

With both Bowie and Kahlo, I always tried to make the character my own, make the drawings my own. I would never emulate something that they have already projected on to themselves; I would never redraw something. I’m not an illustrator. I see myself as a fine artist interpreting what I see and making something new. It’s about capturing their essence. I look at images and then try to forget them. I delete them from my computer. I want to have an initial sponge-like moment and then just let go and start making my own work. Another thing that helped in the case of the Bowie project is that I don’t know his complete biography or discography. I’m not that close to him as subject matter. I think that really helped me to be able to make the works my own, if that makes sense.

AMc: Absolutely. I think it’s similar with writing. If you are writing about an exhibition and read other people’s reviews of it, you have to delete them from your mind before you can write your own afresh.

Coming back, then, to the paper that you mentioned you use. With the Bowie collages, in particular, you have used some quite specific textile papers, ranging from Japanese chiyogami, Nepalese lokta, Dutch gold and hand-blocked papers. What made you choose these, and how were they significant?

HN: I have chests filled with papers with myriad different references, sometimes colour coded. I specifically chose the Japanese papers for this project, because a lot of the compositions look like tunics and Japanese costume, because Bowie was heavily inspired by Japan. In fact, John O’Connell, who wrote the introduction to Diamond Dolls, told me that, when he was in Berlin, Bowie would sleep under a Mishima poster, because he was also very heavily inspired by Yukio Mishima, the writer.

The lokta and the Dutch gold were basically other reference points of which I believe Bowie would have approved because he was a worldly person. He took references from all sorts of international cultures.

Coming back to Kahlo, I also think that she, as time goes by, becomes less Mexican and more international. I’m on the fence as to what is appropriation and what is not. The idea that someone might say to me, that, as an Indian, I shouldn’t interpret Bowie because he’s English, seems crazy. I find it hard, because we’re already in little boxes, and now it feels as if we’re trying to get into ever more specific boxes. It sometimes makes me a bit confused and disoriented when I hear things like that.

Hormazd Narielwalla. Diamond Dolls no. 36, 2021. Mixed media on vintage bespoke tailoring pattern, paper size 42 x 29.7 cm. Copyright Hormazd Narielwalla. Image courtesy Eagle Gallery / EMH Arts, London.

AMc: It does seem crazy when, as in the case of both Kahlo and Bowie, you are referencing icons who have had such a huge impact on your life.

HN: Exactly. For me, it’s about respecting the culture that you’re inspired by and the viewpoints of that culture. Of course, if someone like Gucci were to be inspired specifically by a living, working, 21st-century African artist, blatantly ripping off their work, then that would not be acceptable at all. That would be a clear indication of abuse. But designers are inspired by each other all the time. There’s a ceramicist I follow on Instagram, and he made a post about how white people, specifically Europeans, have an affinity for his ceramics, whereas he’s black American. He got a comment from someone saying: “I can see why people like your ceramics because they follow in the tradition of Grayson Perry.” He got really angry, because Perry is very much inspired by other cultures, so why does he not get comments about his references to African aesthetics? I understand where this ceramicist is coming from.

AMc: Absolutely. Can we backtrack a bit and talk about when you first started making collages? How did that come about, and what inspired you to work in that way?

HN: I was studying for my master’s course at the University of Westminster, which was basically for people who wanted to be in fashion but didn’t know where, so we were allowed to do whatever we wanted. We didn’t have to do a collection. I was really encouraged to create something that was visual, and I kept being drawn to military tailoring and bull-fighter uniforms – for the costume element, not the violence. I went to Savile Row to do some research, and I met a tailor and started talking to him. He told me that, when his clients passed away, he would shred their patterns. After visiting this tailor a few times, I convinced him to give the patterns to me instead. I had always learned that patterns were used to make clothes, and so I had never thought about doing anything else with them, but because these patterns were freed from their utilitarian existence, I realised I could do whatever I wanted, as they no longer needed to serve a purpose in making clothes. I think that was my lightbulb moment when I thought: “Oh my god, I can make things out of patterns.” I’m not saying that was the first time that patterns were used to inform an art practice, because I later identified a lot of designers and artists who put the pattern at the forefront rather than garment. Charlotte Hodes, for example, looks at patterns and talks about feminism by the way women’s patterns curve and move. Shelley Fox, whom I studied under for my PhD at London College of Fashion, uses patterns in the form of a circle, which is very unusual, because the body is not circular. That’s when it really clicked that I wanted to base my practice around patterns. I wrote a letter to Paul Smith, telling him about my work, and he invited me to visit him and then offered me my first solo show in 2009, which was a really exciting moment for me.

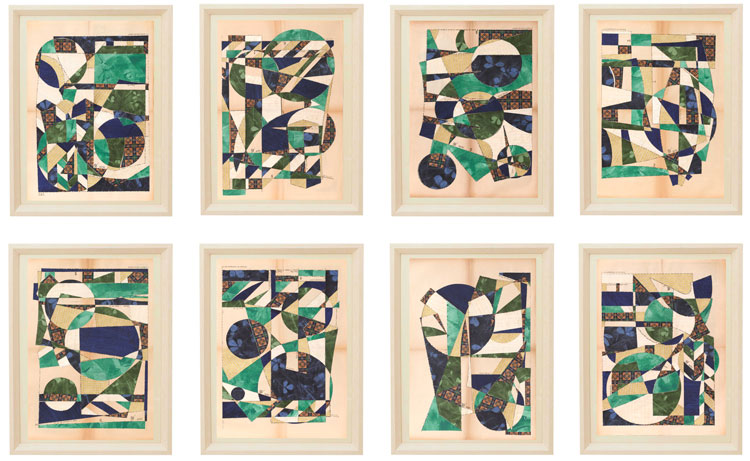

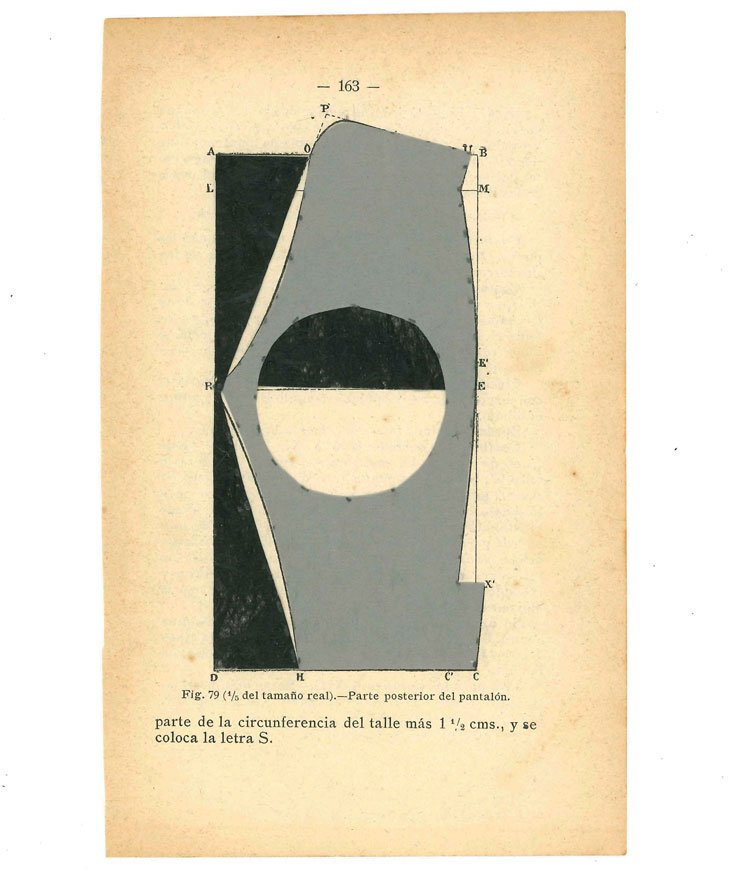

When I finished my PhD, I became a practising artist making work from patterns. An early example is The Love Garden series, a sculpture made out of military uniforms, which was exhibited at Saatchi Gallery during Collect 2013. Then, I made a set of eight collages, Heavenly Bodies (2021), where I inserted circles because, as I said, circles don’t feature in patterns as there’s nothing circular about a human. Even our heads are not absolutely circular.

AMc: I wondered, also, whether there is perhaps something metaphorical about the collage process itself – in terms of fragmented identities and piecing yourself together?

HN: Exactly, yes. Definitely.

Hormazd Narielwalla. Relaxing in the Calm, 2021. Paper collage on sewing pattern, 77 x 55.5 cm. Copyright Hormazd Narielwalla. Image courtesy Eagle Gallery / EMH Arts, London.

AMc: I read that your work is sometimes described as “abstract sculpture”, which, at the time, did not make sense to me, but now I have seen the more non-figurative pieces – and, in fact, sculptural pieces such as Heavenly Bodies – it does.

HN: Yes. I’m also quite heavily influenced by the Bauhaus and the fact that the artists dressed up as sculptures. Sometimes, when I create works, I give a suggestion of a human body part, such as hands or legs. They don’t look like hands or legs, but, when you look at them more closely, they do. You also need to understand that the entire composition is made out of a pattern. It could be for lingerie, or a section of another artwork, which I then superimpose on to the body to suggest a body. In one of the Bowie images, there is a massive circle in the middle. As I said, he was like an alien lifeform for me, and so the idea is that there doesn’t have to be any specific realism to his body.

Hormazd Narielwalla. Heavenly Bodies, 2020. Paper collage on sewing pattern, 65 x 47.5 cm (each panel framed). Copyright Hormazd Narielwalla. Image courtesy Eagle Gallery / EMH Arts, London.

I keep coming back to the Bauhaus as a reference point in my work, because they made such magical theatrical costumes, adorning the body, and with the idea that they could be seen as anything they wanted to be seen as. My Dancing Blocks (2014), for example, take this idea that the abstract can start to show movement. By inserting a circle, I’m starting to find a body within the pattern.

Hormazd Narielwalla. The Prayer, 2020. Paper collage on sewing pattern, 77 x 55.5 cm. Copyright Hormazd Narielwalla, courtesy of Emma Hill Eagle Gallery.

In The Prayer (2020), there’s a person kneeling in prayer; then there’s The Worshipper (2020); and then a person just resting in Relaxing in the Calm (2021). The idea is that they have become sculptural.

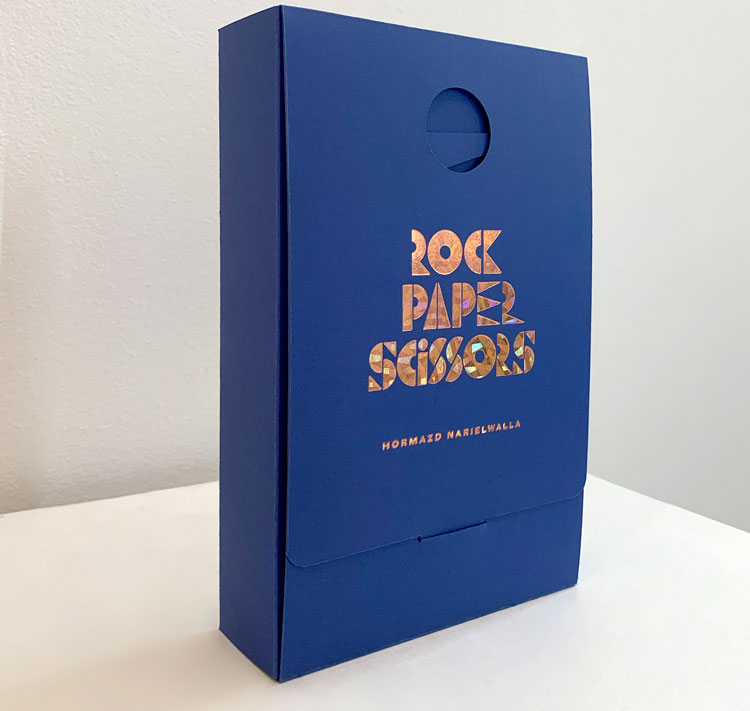

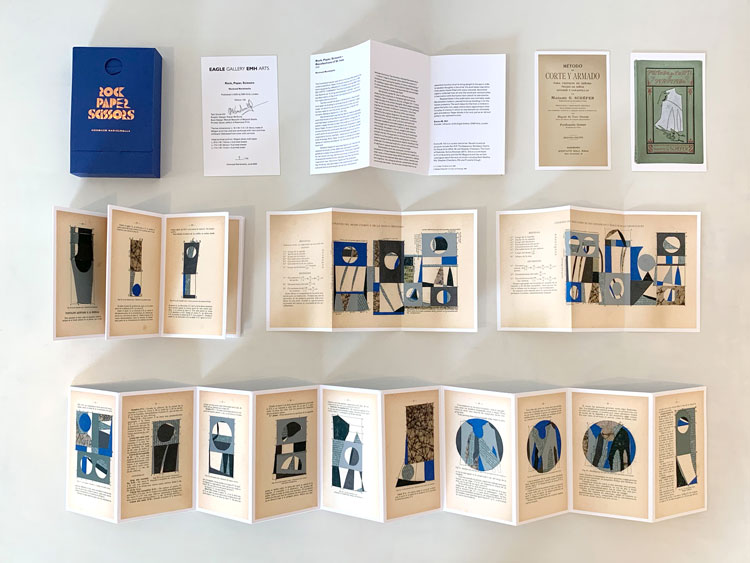

Hormazd Narielwalla. Rock, Paper, Scissors, 2020. Artist’s book, 18 x 11.5 x 3 cm, edition:100. Copyright Hormazd Narielwalla, courtesy of Emma Hill Eagle Gallery.

Also, last year, I made a series called Rock, Paper, Scissors, which was turned into an artist’s book, which was shortlisted for the Trinity Buoy Wharf Drawing Prize. That idea was inspired by Barbara Hepworth’s Sculpture Garden in St Ives, taking that feeling and making miniature collages in response to her monumental sculptures. These were also meant to look sculptural. Patterns are two-dimensional objects, but, in my work, they become three-dimensional pieces of art. They may not have physical three-dimensionality, but they have an essence of three-dimensionality.

Hormazd Narielwalla. Rock, Paper, Scissors, 2020. Artist’s book, 18 x 11.5 x 3 cm, edition:100. Copyright Hormazd Narielwalla, courtesy of Emma Hill Eagle Gallery.

AMc: How do you feel about your work being classified as “drawing” for the Trinity Buoy Wharf Drawing Prize, then?

HN: Well, it was me who applied for it! The Trinity Buoy Wharf Drawing Prize really challenges what is classified as a drawing. The Rock, Paper, Scissors book cover is basically a cutout with a drawn underlayer, and everything happened with that drawing. The cover was designed and started out with a drawing. I also think that every work in the book has an element of drawing to it, since the collage cannot exist without me marking out a precise square within a circle, for example – all of which started with a drawing. The question is: “Can a collage be a drawing?” Well, they thought so. My practice has a lot of dimensions to it. People ask me if I’m a painter, an expressionist, this, that, or the other. I’m just making work that I can relate to, and that my audience can relate to. It’s quite important for me not to put myself in a single box.

Hormazd Narielwalla. Rock, Paper, Scissors, 2020, p163, from the Rock Paper Scissors series, 2020. Paper collage on book leaf, 18 x 11 cm. Copyright Hormazd Narielwalla, courtesy of Emma Hill Eagle Gallery.

AMc: You have just mentioned Rock, Paper, Scissors, and I know you have made other artist’s books as well, before Diamond Dolls. What led you to that, and what is it about the medium that appeals to you?

HN: If you look at my website, there’s a whole section of books. I have done 10 of them now. One – Hungarian Peacocks (2014) – was a one-off, an edition of one. It was made on the pages of a rare Hungarian tailoring manual from the postwar period, called by the same name. Before the first world war, tailoring was dominant in Germany and the Austro-Hungarian empire, and, when that fell, a lot of the tailors migrated to Britain, and Britain became the dominant country for menswear. For that book, I was interested in the feeling of things falling apart. With Sky in a Box (2019), when you open it up, it just erupts into the sky. My idea there was about whether or not we can touch the sky – and even keep it in an internal space. Without the Spirit, There Is Only Material (2020) is created like a book, but then it opens up, and I have printed flesh on to battens that hang, like in a Victorian butcher’s shop. That was a really interesting project. Again, it was a very small edition of five. Anansi Tales (2015) opens up from the centre and comprises drawings inspired by Africa. They are made on brown-paper patterns. I love that book, and made an edition of 15. Then there was Paper Dolls (2018), which was produced by Concentric Editions, which also produced Diamond Dolls. That was about me dressing up as a geisha, and the idea, again, that we can be who we want to be. When Theresa May said: “If you believe you are a citizen of the world, you are a citizen of nowhere,” I found it very irresponsible, because we all have different parts to our identity. I’m British, but that doesn’t mean I have to give up my Indian heritage or my Persian ancestry. According to her, though, I do. That comment led to that book, which won best limited edition at the British Book Design and Production Awards. I was pretty excited by that. I should also mention Dead Man’s Patterns (2008), which was an edition of 100 and a phenomenal success. The British Library bought one, as did the National Art Library at the V&A, and several other institutions in the UK and the US. It was thanks to that book that I got my PhD funding.

Overall, the artist’s book is a very important vehicle for communicating my ideas because the patterns are paper based, and they act like books, in a way, because you have to open them and riffle through them, and they start to look like pages.

AMc: You have just described some fascinating books, which each open in their own idiosyncratic ways – not like a standard book with pages turning from one to whatever. How does Diamond Dolls work? Am I right in thinking it comprises three mini “booklets”?

HN: Yes, there are three booklets, which open out like Japanese shoji screens. It’s really a sculpture that turns into a book (or vice versa). When we were in lockdown, we had to consume art in a very different way – either it was on our screen, or on our walls, and so, when you receive this book, it’s as if the exhibition were coming to you. It is a symptom of the times we were living in. The idea is that the booklets should sit on three shelves, and the book comes alive and starts performing, because the muse was a performer. We also printed the backs of the artworks, which reinforced the notion that it was Bowie’s spirit I was interested in. They look like accidental Russian constructivist prints, which I find rather lovely.

Hormazd Narielwalla. Diamond Dolls, 2021. Copyright Hormazd Narielwalla, image courtesy Eagle Gallery / EMH Arts, London.

AMc: Everything is held together on the reverse with tape.

HN: On the originals, yes. I work by slicing into the paper and then layering things. Some of the collages have five, six layers to them, to create the idea of adornment. What fascinates me about the muses I have chosen to work with – Bowie, Kahlo, Coco Chanel, Klaus Nomi – is the idea that they use dress, textile and clothes to communicate an identity that is unique to them.

AMc: Tactility is such a key part of art as well, rather than just seeing a flattened version on a screen, and this is made even more emphatic in an artist’s book.

HN: Absolutely. We can reach a bigger audience via a screen, but you will never be able to touch a book, feel the embossing or smell it. Our senses, too, are multilayered. When we look at screens, we can never truly feel a painting, or, if you are looking at a print, you can’t smell the ink.

AMc: You mentioned earlier that Diamond Dolls has an introduction by John O’Connell.

HN: Yes. He’s the author of Bowie’s Books: The Hundred Literary Heroes Who Changed His Life (Bloomsbury, 2019). It came about accidentally, because he became a collector of mine just as I was doing this project on Bowie. It was clearly meant to be. I approached him and asked whether he would write the introduction, and he graciously accepted. I was thrilled.

AMc: Is it normal for your artist’s books to have an introduction?

HN: Yes. Emma Hill, who runs the Eagle Gallery, where Diamond Dolls is being shown, wrote the introduction for Rock, Paper, Scissors. For Paper Dolls, Gill Saunders, the curator at the V&A, wrote the introduction. It’s always interesting when someone else introduces the work, because I feel my job is done when the works exist, and someone else’s interpretation of them is far more interesting for me – and others – to see and read than my own would be.

AMc: What will people be able to see in the Diamond Dolls exhibition, apart from the book and the original collages? And will the collages be visible so that you can see the amazing taped-up constructivist backs as well?

HN: Sadly not. Once they are framed, the backs disappear, but we’re not framing all the works, so there will be some that can be looked at more closely. The book will also be on display in JP Hackett, No 14 Savile Row, London, and Essie Sakhai is giving me one of the windows at Essie Carpets, Piccadilly, too. Essie and Caroline Cole of ACC Art collaborated with me on The Creation (2020), which is a stupendously gorgeous carpet, so both the carpet and the book will be installed in the window. We weren’t sure whether lockdown would finally be lifted, so we wanted people to at least have the chance of walking past a shop window and seeing the book. Then, the reason for choosing JP Hackett is twofold: first, it has a permanent collection of about 30 pieces of mine, but, more importantly, it just so happens that its fire escape door is right outside the phone box Bowie used for the Ziggy Stardust album cover. When I found that out, it was a no-brainer!

• Diamond Dolls will run until 7 August 2021 at the Eagle Gallery, London. The book is also on display at JP Hackett, No 14 Savile Row and in the window of Essie Carpets, Piccadilly until 15 August 2021.