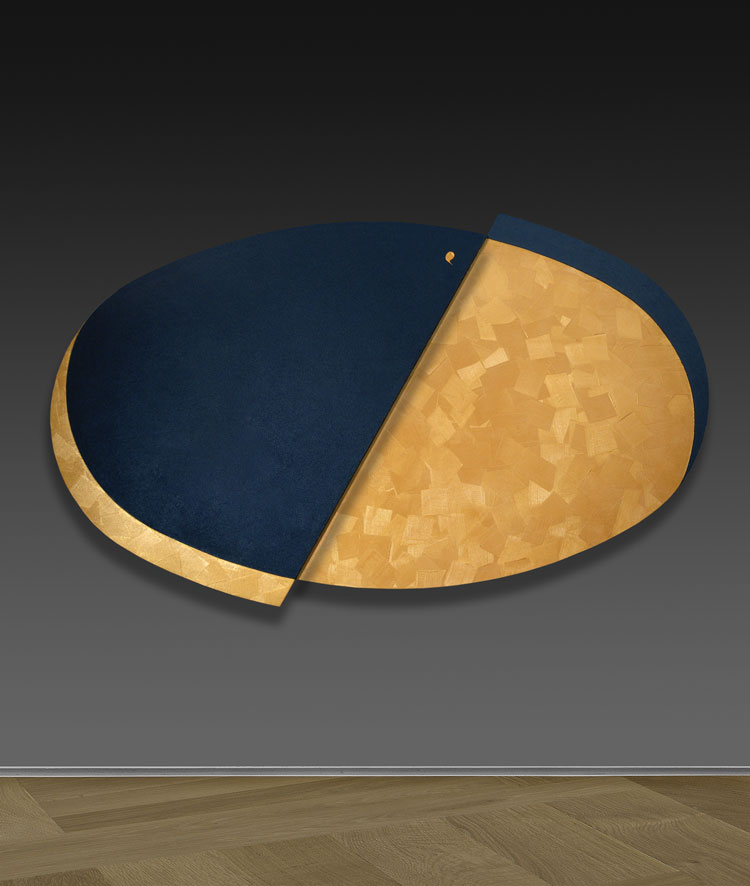

Gianfranco Zappettini: The Golden Age, installation view, Mazzoleni London, Courtesy London-Torino.

by ANGERIA RIGAMONTI di CUTÒ

Born in Genoa in 1939, Gianfranco Zappettini has always shunned doing things by the book. Before turning to painting, he created animated graphics for the Italian steel corporation Italsider’s Filmrelazione, ostensibly an industrial film, though above all a manic glorification of Italy’s postwar economic miracle. But rather than be swept up in the boom of Italian cinema, or the conceptual tendencies of his native city’s arte povera, Zappettini devoted himself to pittura analitica, a hermetic current that strove to rationally and systematically investigate the processes and syntax of painting itself. At radical odds with the profusion of non-formalist and performative movements that had disdainfully and portentously declared the death of painting, pittura analitica persisted. But when painting was readmitted to the doctrinaire status quo in the 80s, in the form of neo-expressionism, Zappettini retreated from the art world. Marking a departure from the procedural scope of his analytical era, an investigation of eastern philosophies introduced a numinous aspect to the later works, integrating a meditative function of painting that also accommodated a third dimension and an unexpected recourse to the allure of gold, the centre of this exhibition of new works.

Gianfranco Zappettini. Con-Centro no 103, 2018. Resins, facade plaster and acrylic on board, 290 x 330 cm. Courtesy Mazzoleni, London-Torino.

Angeria Rigamonti di Cutò: You have always been committed to the medium of painting, but looking at your early formation it seems that applied arts might have affected your development. Early on you did some graphic work, creating animation for an industrial film made by the Taviani brothers, and you undertook an apprenticeship with the German architect Konrad Wachsmann who had collaborated with Walter Gropius. How did those experiences inform you? Were you ever tempted to follow a more practical path in a graphic or architectural field?

Gianfranco Zappettini: No, and I’ll tell you why. In my early 20s, Italian cinema seemed like the El Dorado everyone was after. Let’s not forget it was the period of the Dolce Vita. I was lucky enough to encounter the world of Cinecittà thanks to a small commission as a graphic artist for an industrial film. I learned the dynamics of that world and realised that to get top results you had to work extremely hard and absorb from the best.

Back in Genoa, I found one of these “best”: Konrad Wachsmann, a pupil of Walter Gropius, one of the greats of the Bauhaus. He was a perfect maestro because it wasn’t his aim to make me a replica of himself – another architect – but rather to teach me certain principles. Precision, punctuality, mental clarity, and, in the context of work, a taste for the internal equilibrium of an artwork, a refusal to improvise, the need for the work to be anchored in the real world (starting from the materials it’s composed of).

So, I never wanted to become an architect or a graphic artist, but tried to grasp the secrets of good architects and graphic artists while continuing to think in terms of painting.

Gianfranco Zappettini. Con-Centro no 28, 2019. Resins, facade plaster and acrylic on board, 170 x 170 cm. Courtesy Mazzoleni, London-Torino.

ARC: In a 1976 interview with Studio International, you declared a commitment to renewing the autonomous medium of painting at a time when it had allegedly become obsolete, at least according to the dictates of Joseph Kosuth in his classic 1969 text Art After Philosophy, also published in Studio International.

How difficult was it to go against the grain, particularly since Italy – and indeed your own city of Genoa – was such an important locus for the more dominant conceptual currents such as arte povera?

GZ: At that time, Genoa was a very fertile terrain for various reasons: not only in terms of art, but also music, with an important school of singer-songwriters such as Fabrizio De André, Luigi Tenco, Gino Paoli; or even its university, where the multifaceted art historian and critic Eugenio Battisti taught, or even just the political battles that found a kind of “frontline” in the city.

So, it was already a vibrant and, in some ways, nonconformist place, where everything and its opposite was possible. To go against the grain wasn’t as hard for me (in my life, especially later, I nearly always struck unconventional paths) as it was for those close to me: other artists who dreamed of glory, critics in search of power or gallerists who wanted wealth.

It was hard for those who wanted “everything, right now”. I knew my path wasn’t in the mainstream, especially in the realm of painting. In Kassel, in 1977, seeing the huge coloured canvases of Georg Baselitz, I wanted to exhibit my superimposed, white, glacial, almost untouched canvases, even though I knew people’s eyes would be enticed elsewhere. I soon learned how to live with the pros and cons of the “counter-current”.

Gianfranco Zappettini. La trama e l'ordito n. 81 - la Luce Prima, 2017. Resin, acrylic on board and black light, 180 x 187 cm. Courtesy Mazzoleni, London-Torino.

ARC: By the early 80s, there was a revival of painting, though in a form that seems just as distant to your analytical abstraction as conceptual art had been 10 years earlier: the painterly current referred to as neo-expressionism. How did you respond to this “return” of painting? It is said that you opted for a self-imposed isolation in that decade?

GZ: It’s true, but it’s no secret, I write it in all the biographies that end up in catalogues. I voluntarily chose not to exhibit and opted out of the circuit of the market, galleries, critics and art fairs because, at 40, having already had everything from painting – fame, money, international museums, an invitation to exhibit at Documenta (I’ll even add the 1976 Studio International interview) – I thought it was time to understand whether there was anything beyond all this worth living for. From there, I started traveling towards a geographic east, in search of a metaphysical orient, precisely to “orientate” myself. Then, while I was doing this, in Europe and beyond, painting resurged for the hundredth time, demonstrating that I was right and Kosuth wrong.

And I immodestly believe that the analysis of pictorial language undertaken by me and my travel companions contributed to that return of painting. Then, of course, I considered transavanguardia a flash in the pan, consisting of ugly painting and poor technique – and, again, time proved me right. But I’m still glad it existed because it was like a “homecoming” for art. Painting is intrinsic to mankind, like the word: it will die when the last person on earth dies, and conceptual or visual artists – whom I respect – have to come to terms with this. The same applies to those who simply pretend to be conceptual artists because they don’t know how to draw a foot or an apple.

ARC: A later phase of yours, included in the current exhibition, was your Weft and Warp series (La Trama e l’Ordito), more tactile works that incorporate the layering of the industrial mesh WallNet, used in masonry construction, though this series also engaged with the more handmade, craft tradition of Ligurian macramé. Some of your earlier works of the analiticaphase also integrated layered fabrics that you overpainted. Why are you interested in extending into a third dimension within the realm of painting?

GZ: It’s true, the concept of layering has always interested me, it’s enough to think of my layered canvases of the 70s, and, earlier still, the plastics that sheathed my works of the 60s, revealing the underlying structure. In the current La Trama e l’Ordito series, I’ve shifted from the purely process-driven approach of the analitica phase to a painting practice enriched by symbolic meanings linked to weaving, understood as a support to spiritual fulfilment. But throughout these phases I’ve maintained that interest that you refer to. Not only in a third dimension in painting, real or imagined – one of my great maestros, incidentally, was Lucio Fontana – but in actually investigating the very essence of painting which is nothing but the stratification of colour. I’m thinking of my “analytic whites” of the 70s, in which I layered coats of white over a preparatory black surface.

Gianfranco Zappettini: The Golden Age, installation view, Mazzoleni London, Courtesy London-Torino.

ARC: You took that three-dimensionality even further when you recently made a large-scale installation-environment of suspended and layered meshes that occupied the surrounding space (La Luce Prima). This seems to be a real departure from painting, assuming that you understand painting to be dependent on an underlying support?

GZ: When I created the installation with suspended mesh at my solo exhibition La Luce Prima [The First Light] at the Primo Marella gallery in Milan, I added a third dimension to the horizontality and verticality of the weft and the warp: depth. The spectator could not only look at the work, but also penetrate and interact with it. The rarefaction of both painting and the supporting material made the space both real and imaginary. I’ve always had a penchant for the spatial and scenographic context of my exhibitions, perhaps a throwback to my beginnings at Cinecittà or my collaboration with Wachsmann. The Milanese exhibition was also a “quotation” of an exhibition I did in a museum in Antwerp in 1978, where instead of mesh I used paper. But it was still about painting.

ARC: You undertook a phase of travel and spiritual research, investigating disciplines such as Taoism, Zen Buddhism and Sufism. How did that study inform your painting?

GZ: Those studies influenced my work a great deal because approaching the metaphysical doctrine I found the centre I was searching for, even in the deepest sense of my being a painter. Since then, painting has become a ritual gesture and the works have been enriched by symbols, present in eastern and western traditions, that have passed through every era to bring us the last fragments of true enlightenment. It was as if I were an ancient monk, working day after day as a manuscript illuminator as a form of meditation.

Gianfranco Zappettini. Il petalo d'oro no. 15, 2019. Resins, facade plaster and acrylic on board, 160 x 256 cm. Courtesy Mazzoleni, London-Torino.

ARC: In your most recent work, the focus of this exhibition, you have introduced patterned gold surfaces on your painting-objects. The use of such an auratic colour marks a strong contrast to the often industrial-mechanical processes, materials or colours that you integrated in earlier works. Why were you interested in using gold and how does these works relate to the analitica phase? Apart from the obvious reference to the dominant colour, does the idea of the Golden Age also have a theoretical raison être?

GZ: Gold characterises my most recent works and is a throwback to a tradition that goes back not only to sacred icons, but also to early Renaissance painters such as Fra Angelico, the Lorenzetti brothers and others who used a gold ground to exalt the transcendental dimension of their works. Highly precious and incorruptible, gold is spiritual light and alludes to that aurea aestas [golden age] in which everything was in perfect harmony, an era – according to mythology – that must return because the end and the beginning coincide in the perpetual cycles of time.

Some of these most recent works, being three-dimensional, take on a corporeal aspect that places them at the threshold between sculpted painting and painted sculpture. The symmetrical, open forms that determine their structure create a subtle tension both within the work and between the work and the surrounding space, in a sort of equilibrium that is recreated with every look.

Gianfranco Zappettini. Il codice degli dei no 35. Resin and acrylic on board, 9 x 50 x 50 cm. Courtesy Mazzoleni, London-Torino.

ARC: Now that we have apparently lived through every conceivable modernist and postmodernist cycle of exalting and repudiating painting, can the medium be worked in new ways?

GZ: The only novelty or scope for discovery is within the realm of materials of which there is an infinite variety today. I imagine what the masters of the past could have done with the glues, resins and acrylics available today. I wonder, for instance, what Cézanne might have achieved, even though he was technically proficient and died only 33 years before I was born.

Otherwise, we need to perfect rather than invent, in my modest opinion. What is lacking today is an in-depth knowledge not only of Tradition with a capital T (and this is understandable: we have reached the end of time and that type of knowledge is not for everyone), but also tradition with a small t. I’m talking about the pictorial tradition, above all – though not only – Italian, but also traditions of technology, iconography, the function and value of colour within the context of composition, whether figurative or abstract is of no importance. As I’ve been saying since the 70s, there’s no reason to be worried: painting always survives. Let’s at least try to really know it.

• Gianfranco Zappettini: The Golden Age, curated by Martin Holman, is at Mazzoleni London until 11 April 2020.