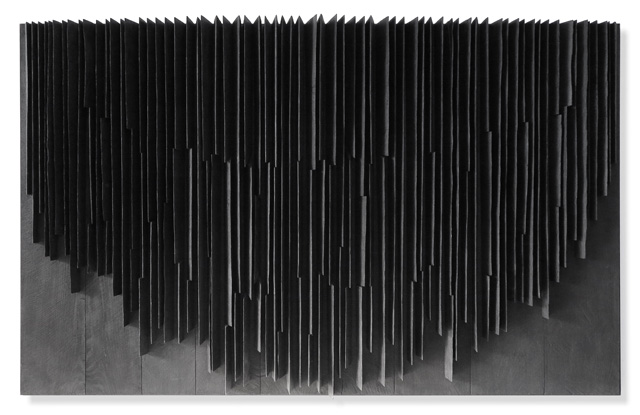

Nunzio: The Shock of Objectivity, installation view, Mazzoleni, London, 2019. Courtesy Mazzoleni, London-Torino.

Mazzoleni, London

7 June – 7 September 2019

by ANGERIA RIGAMONTI di CUTÒ

Born in Cagnano Amiterno, L'Aquila, in 1954, Nunzio graduated from the Accademia di Belle Arti, Rome, where he studied set design with Toti Scialoja, a poet, theatre designer and painter who had been strongly marked by encounters with abstract expressionists such as Robert Motherwell and Willem de Kooning, and who had also taught the arte povera exponents Pino Pascali and Jannis Kounellis. This composite of disparate visual languages is worth keeping in mind on viewing this exhibition.

Nunzio: The Shock of Objectivity, installation view, Mazzoleni, London, 2019. Courtesy Mazzoleni, London-Torino.

Nunzio went on to become the only sculptor in the loose collective of six artists known as the San Lorenzo group and was the first to occupy an abandoned pasta factory in the working-class Roman district from which the group took its name. (It was also in that industrial building that the now quasi-mythological photographer Francesca Woodman, a friend of the group, created some of her most memorable images.) The San Lorenzo group is sometimes viewed as a late offshoot of the Transavanguardia, Italy’s contribution to an international revival of figuration and expressionism in the 1970s and 80s, following a near-hegemony of abstraction and conceptualism. Associating the two groups is misleading, if predictable, given that the early in situ exhibition of the San Lorenzo group in 1984, Ateliers, was curated by the influential critic Achille Bonito Oliva, who had coined the term Transavanguardia.

Nunzio, Sera, 1991. Combustion on wood, 106 x 55 x 17.5 cm. Courtesy Mazzoleni, London-Torino.

In 1986, Nunzio was awarded the prize for best young artist at the Venice Biennale and, a few years later, received an honourable mention for his space at the 1995 edition of the biennale. Initial experiments included a singular hybrid of media, works on plaster painted by immersion in watercolour and exhibited leaning against the gallery wall – a telling indication of the ambiguity of their formal status. Other unusual materials favoured by Nunzio were wax, tar and lead. Early on, he began experimenting with his signature amalgamation of material and technique (the two sometimes being hard to separate in his work): combusted wood.

Nunzio, Avvoltoio, 2019. Pigment and combustion on wood, 238 x 252 x 130 cm. Courtesy Mazzoleni, London-Torino.

The display at Mazzoleni, curated by Kenneth Baker, consists of 16 well-chosen works from the past 30 years broadly divided between sculptures of burnt wood (some freestanding, a few prone, others hanging), as well as quietly burnished lead reliefs. The largest sculpture, Avvoltoio (vulture), was conceived expressly for the gallery and should ideally be experienced in person. Well over two metres tall, its rhythmic profusion of almost 200 fillets of undulating oak has been charred with a blowtorch, giving it the friable finish of bark, its fluctuating shades of blackness an integral part of its allure.

Nunzio uses a chainsaw to shape his cauterised wood, a gesture that might seem antagonist, even destructive, but he contends that the process is a delicate one, the saw barely grazing the material’s surface but nonetheless transforming it. Avvoltoio is characterised by another trademark, the sparing application of ultramarine paint on the edge of the crisped wood, even more potent for its rarity within an otherwise sober palette. The combination of fire and deep blue inescapably recalls Yves Klein.

-IMG_0799.jpg)

Nunzio, Avvoltoio, 2019 (detail). Pigment and combustion on wood, 238 x 252 x 130 cm. Courtesy Mazzoleni, London-Torino.

The forms of all the sculptures are assertively distilled and all the more commanding for it – Brancusi comes to mind and presumably few Italian artists working after the 70s would have been immune to aspects of arte povera, itself a current of disparate impulses that went well beyond an interest in lowly materials.

The second component of the display, lead reliefs on wood, exemplifies Nunzio’s resolve to fuse apparently discordant or even unappealing materials. There are precedents for lead reliefs in postwar art, most notably by Jasper Johns, but this demanding substance has arguably never been manipulated with such virtuosity, attaining such precision and lustre as it does in Nunzio’s concave geometries, results presumably achieved only with prodigious time and effort. One of the most compelling aspects throughout is the way in which the complex transmutation of lead and wood renders the surface of the works almost painterly, and even overtly beautiful. These qualities seem at odds with Nunzio’s claim, expressed in an interview published in the exhibition catalogue, that he is uninterested in modifying the surface of his works or heightening their aesthetic appeal.

Nunzio, Untitled, 2019. Combustion on wood, 115 x 185 x 15 cm. Courtesy Mazzoleni, London-Torino.

Seeking links between artists and external forces can be a hazardous initiative. In this respect, the connections proposed in the catalogue text are sometimes strained, not to say fanciful, the type of accretions of interpretation that Susan Sontag railed against in her rallying cry Against Interpretation. Thus Nunzio’s blackened wood is read as speaking of an ambitious array of phenomena, from both transience and inertia to various global catastrophes, regardless of their historical specificity, whether forest fires and the burgeoning dread of incineration by nuclear combat, or the fear of darkness provoked by cybernetic warfare.

Comparisons made with artists who often used black – among others Louise Nevelson, Ad Reinhardt and Tony Smith – are less overreaching, although, outside the confines of American art, a consideration of Pierre Soulages would be apt. Baker justly contends that making connections with other artists can seem defensive and risks curtailing the power of Nunzio’s art, but nonetheless proposes further, and at times frankly grandiloquent, lines of reasoning to explain the “shock” of the show’s title.

Nunzio, Mercurio, 1990. Lead and combustion on wood, 128 x 119 x 3 cm. Courtesy Mazzoleni, London-Torino.

In an account that predicts audience response – which seems a disservice both to the art and its spectators – Baker maintains that on first encounter with Nunzio’s sculpture: “Viewers … will feel an unfamiliar sort of shock – not merely the surprise of unfamiliarity, but the essential shock of objects’ existence, ontologically indifferent to our sense of ourselves, aesthetically indifferent to our performance of response. Through this sensation, his art shames our self-importance … This experience sparks a tremor from beneath the level of political solidarity or collective activism.” (A similar existential shock is identified in two works by Walter De Maria, Ball Drop and the land art work The Lightning Field, the shock triggered, respectively, by the loud bang of a dropped ball and by lightning striking the Earth).

But Nunzio’s otherworldly objects, almost apparitions, easily stand on their own, self-evident merits and undeniable elemental power and formal refinement. In one respect, these works seem very distant from one of the leitmotifs, even platitudes, of so many postwar artistic currents, namely the collapsing of the art-life divide that had been so sacrosanct to modernism. The space inhabited by these remarkable structures feels apart, distinctly “other”, as some would still, at times, wish art to be.