Olivia Erlanger, installation at And Now, Frieze New York 2019. Photograph courtesy Frieze.

Randall’s Island Park, New York

2-5 May 2019

by NATASHA KURCHANOVA

This year’s Frieze had a pronounced tendency to please the market rather than to rock it. With more than 200 participating galleries, established dealers showed recognised artists who are already well known or are making names for themselves with exhibitions at major New York museums. Among the former were the Gagosian Gallery, exhibiting John Chamberlain’s (1927-2011) iconic sculptures made of mangled metal and Steven Parrino’s (1958-2005) manipulated paintings that match Chamberlain’s forceful handling of industrial materials.

David Zwirner booth at Frieze New York 2019. Courtesy David Zwirner.

David Zwirner chose to show Christopher Williams (b1956), who has become a household name in recent years with the skilful development of his own high-gloss finish style of photographic documentation. In addition to Williams, Zwirner also exhibited works by the up-and-coming Belgian artist Harold Ancart (b1980), who has produced gigantic paintings of handball courts with ambiguous objects smack in the middle, resembling a handball on top of a stick. The singularity of his subject matter is counterbalanced by the multiplicity of ways in which this subject is treated: the courts vary greatly in background, brushwork and colour combinations, making the work appear somewhat shabby and careless, indicative of the artist’s indifference about pleasing the eye.

Yayoi Kusama, Narcissus Garden, 1966-. Stainless steel spheres, 34 cm diameter each. At Frieze New York 2019. Photo © Natasha Kurchanova.

It was interesting to juxtapose Ancart’s painting, which brags about its apparent casualness and self-deprecating qualities, with a classic work from the 1960s by Yayoi Kusama (b1929), whose Narcissus Garden (1966-) carries a diametrically opposing message. The work covered the entire floor of the installation with perfectly round spheres made of polished steel, a bit larger than a foot in diameter. The polished surface of the spheres allowed the visitor to see her own reflection, connecting to the viewer on a closely personal level.

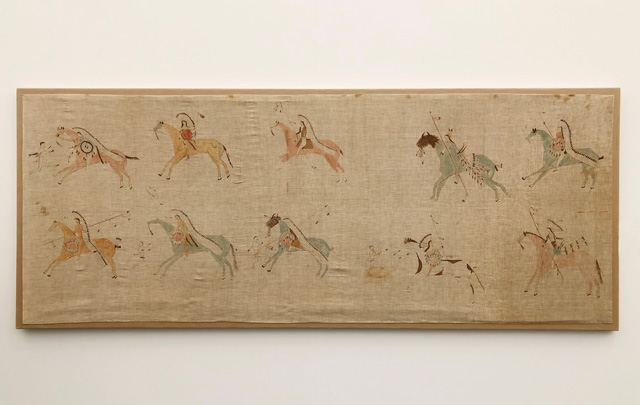

Pictographic Muslin, Sioux Northern Plains c1890. Ink and coloured ink on muslin, 32 × 82 1/2 in. Courtesy Donald Ellis Gallery.

An escape from self-deprecation on the one hand and narcissism on the other was found in the self-reliant simplicity and dignity of Native American art, on display at Donald Ellis Gallery. Here, there were mostly decorative paintings, drawings and artefacts depicting warriors on horses, members of the Indian community and traditional ornamental patterns. They were made by the American Indians in the second half of the 19th and the first half of the 20th century, following their conquest by the US army.

Several curated sections were a draw at this year’s Frieze. Foremost among them was a tribute section devoted to the activity of Linda Goode Bryant (b1949), a film-maker and the founder of Just Above Midtown (known as JAM), the first not-for-profit gallery in New York dedicated to showing work by artists of colour.

Linda Goode Bryant and Karen Jenkins Johnson. Photograph courtesy Frieze.

During its 12-year run from 1974 to 1986, the gallery launched the careers of several artists, among them David Hammons, Senga Nengudi and Norman Lewis. At the fair, Goode Bryant was promoting her most recent initiative, Project Eats, a not-for-profit venture that transforms small plots of land into larger farms that employ community members and supply food to low-income New York neighbourhoods. At the fair, Goode Bryant was at a table covered with seedlings, distributing information about Eats. Her easy accessibility and lack of interest in selling things set her apart from the rest of the fair and highlighted her socially conscious practice.

The JAM section of Frieze, inspired by Goode Bryant’s earlier socially conscious activity, included seven galleries representing several artists whose careers began at JAM. Most unexpected among them was Ming Smith, represented by Jenkins Johnson Gallery. An African-American photographer and a long-time resident of New York City, Smith documented the life of her community from 1970 until 1990 with her photographs focusing on people and their daily activities. Sometimes the images are posed – as in her self-portraits – and sometimes they look like snapshots – but in every instance they capture a special, respectful relationship that the photographer establishes with her subjects.

The Doors of Perception, Frieze New York 2019, Installation view with Shinichi Sawada’s ceramics in the foreground. Photo: Olya Vysotskaya.

The Doors of Perceptions, curated by the Venezuelan artist Javier Téllez (b1969), was another notable section of the fair that focused on art made on the fringes of society. Dedicated to outsider and self-taught art, the installation presented more than 300 paintings, works on paper and three-dimensional objects made by an international contingent of artists who created their own imaginary worlds, nearly always mystical, sometimes highly ornamental, and almost always filled with a great multitude of detail.

Echoing the fair’s geographic proximity to the Manhattan Psychiatric Center, a facility for people with mental illness, some of whom are artistically gifted, the organisers of this year’s Frieze managed to enrich the content of their display by including the so-called “outsider” art. The play of energy, fantasy and imagination that enlivened these works often competed with the best examples of properly “schooled” and socially vetted art at the fair. Téllez calls these artists “visionary”. He says outsider artists “often think of the future as a parallel dimension to the present. For them, time is a perpetual possibility, having invented codes to access a new consciousness beyond the flat world of appearances.” The visitor was invited to enter these worlds and revel in their infinite potentialities.

Electric curated by Daniel Birnbaum. Photograph courtesy Frieze.

Other ways to enter infinite potentialities of fantasy and imagination is through technology. It was, perhaps, not by chance that Electric, another popular draw at the fair, was adjacent to The Doors of Perception. Curated by Daniel Birnbaum, former director of the Moderna Museet in Stockholm and currently artistic director of the virtual reality production company Acute Art, this section features seven virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) works by artists including Anish Kapoor (b1954), Nathalie Djurberg (b1978) & Hans Berg (b1978), RH Quaytman (b1961) and Koo Jeong A (b1967).

Visitors were given 3D VR equipment to view these artists’ works, and except for those in the early morning hours, all the available slots were taken; anyone who did not sign up for a time slot at the beginning of the day was out of luck. I was fortunate to be allowed to use my journalistic privilege to watch Kapoor’s breathtaking imaginary journey through one’s own body, called Into Yourself, Fall. I was able to see the other works from Electric at home, as, on my exit, I was given some simple VR-viewing equipment made out of cardboard and instructions for downloading an Acute Art app to my smartphone.

.jpg)

Dora Longo Bahia. Fugue (second voice: Gekide), 2019. Acrylic paint on both sides of linen canvas and augmented reality. 230 x 128 cm. Photo: Edouard Fraipont. Courtesy Galeria Vermelho.

While the VR section is a new addition to the fair, the incorporation of technology into a more traditional, frame-based format of work that could be hung on a wall was also present. Among them were video paintings by Brian Bress (b1975), an American artist who frames videos and displays them on walls like paintings, and Dora Longo Bahia (b1961), an artist from Brazil, who uses AR technology to embed secondary, representational, images into her seemingly abstract works. The hidden images in Longo Bahia’s paintings are revealed on reading a QR code with the help of an smartphone. The disclosed images are rich in content; they depict people’s suffering caused by political injustice and turmoil: in the paintings on view at the fair, there were migrant women hugging their children closely, Madonna-style, trying to protect them from possible calamities and ongoing violence.

.jpg)

Takahiko Iimura, film installation, 1974. Frieze New York 2019. Image courtesy Microscope Gallery.

Among the familiar sections of the fair, Frame, Focus and Spotlight offered some pleasant surprises in the areas of traditional modernism and cutting-edge contemporary art. Microscope Gallery from Brooklyn inaugurated its entrance to Frieze by showing Film Installation (1974) by Takahiko Iimura (b1937), a Japanese artist, who explored material possibilities of film projection technologies. In Film Installation, the apparatus of film projection is displayed as an architectural and sculptural environment, inviting the viewer to pay attention to her experience of space, as opposed to focusing her attention on the image on the screen. Adjacent to the Microscope booth was an attention-grabbing installation of washing machines with gigantic mermaid tails protruding from them. The impression was of a pretty mermaid being sucked inside the centrifugal drum. Made by the New York artist Olivia Erlanger (b1990), the work reminded the locals of the yearly Mermaid Parade that takes place on Coney Island, made famous by the participation of the artistic community, particularly female artists, who produce a great variety of mermaid-themed costumes for this event. Erlanger’s work draws attention to the tragic aspect surrounding the image of a mermaid: both a muse and a demon, the mythological creature ends up being swallowed up by a technological household device.

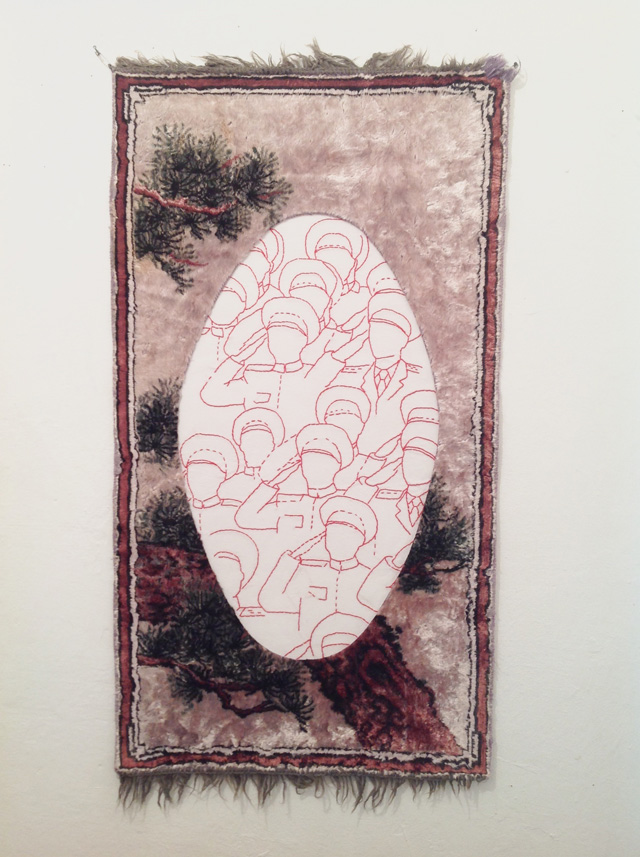

Iulia Toma, Untitled, 2017. Mixed media (drawing with the sewing machine on canvas, carpet), 92 x 50 cm (36 ¼ x 19 2/3 in.) Courtesy the artist and Ivan Gallery, Bucharest. Photo © Catalin Olteanu.

Other pleasant discoveries at the fair included mixed-media works by the Romanian artist Iulia Toma (b1974). Toma, who is represented by Ivan Gallery, showed several works made from textiles, among them Untitled (2017), a drawing made with a sewing machine embedded in a carpet. Material chosen by the artist is specific to her subject matter – Romania’s militaristic history. Embedding the drawing of military men saluting during a parade into a locally woven carpet adds a tangible, tactile quality to an ideational, historical narrative. London-based Pi Artworks showed delicate ink drawings on tracing paper by Susan Hefuna (b1962), who transmits through them her interest in the positioning of the body in space. Dastan’s Basement, a gallery from Tehran, presented figurative portrait drawings by Bijan Saffari (1933-2019), a member of the Iranian royal family who left his home country after the 1979 revolution.

Susan Hefuna, Window, 1999. Ink on tracing paper, 23 x 18 cm. Image courtesy Pi Artworks, London and Istanbul.

This year’s Frieze demonstrated a more open-ended approach than usual by choosing to exhibit and promote diverse art-making practices. By devoting significant attention to new trends, as well as to forgotten and little-known artists, the organisers succeeded in creating a well-balanced and engaging display that included a great variety of visual styles and approaches to art-making, indicating ways not only to continuously expand, but also to challenge the possibilities of the art market.