Wassily Kandinsky. Improvisation Deluge, 1913. Lenbachhaus Munich, Donation of Gabriele Münter, 1957.

Tate Modern, London

25 April – 20 October 2024

by ANNA McNAY

This exhibition opens with a question to its visitors: “What comes to mind when you picture expressionism?” The introductory wall panel goes on to provide a – tentative? – answer: “On the one hand, bold experiments with colour, dramatic forms, atonal music and poetry in free verse. On the other, cross-cultural artistic collaborations set against the imperial ideologies and social inequalities of early 20th-century Europe.” Indeed, this exhibition of more than 131 works, 50 of which have never before been shown in the UK, covers all these bases, but, by focusing on a limited time period (of a decade, give or take), drawing out the relationships between the artists involved, and going back to basics in thinking about who and what the Blue Rider was, the curation enjoys a clear focus and reduces the overwhelm so often found in large-scale Tate exhibitions intent on pursuing academic theses. In an effort to bring women more into the spotlight, showcasing their work on an equal footing to that of their male counterparts, the exhibition further introduces several artists I had not previously encountered (or, at least, not previously encountered as artists). And, as the first Blue Rider exhibition in the UK in 64 years (the previous one also having been at Tate), this celebration of international friendships, colour, form and spirituality is long overdue.

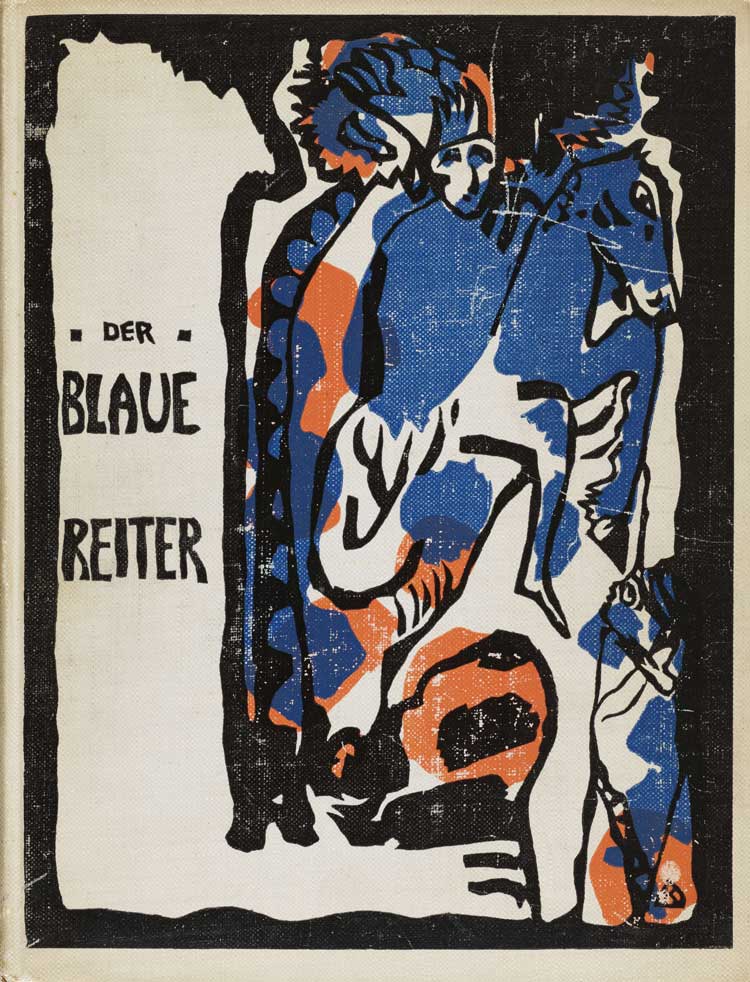

Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc. Der Blaue Reiter, R. Piper & Co., Munich, 1912. Book cover. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

“The Blue Rider’s historiography,” writes curator Natalia Sidlina in her introduction to the exhibition catalogue, “presents it as a Munich-based group founded in 1911 by Kandinsky and Marc, who in 1911-12 organised the First and Second Exhibition of the Blue Rider Editorial Board and published an illustrated volume of collected texts by artists and musicians juxtaposing modernist art and contemporary trends with tradition.”1 The fact that the group was, in essence, an editorial board reframes it with fewer key players but many more in its wider circle. By approaching things in this way, the curators have also been able to really get to grips with contextualising the group internationally and in terms of what else was happening in Germany at the time. One room, for example, explores the roots shared and ongoing bonds with the New Artists’ Association of Munich (NKVM), while, looking to the north, we also learn about the differences from and overlaps with Der Sturm (a Berlin-based magazine – and, later, gallery – similarly focusing on expressionism) and Die Brücke (a group of German expressionist artists formed in Dresden in 1905).

Wassily Kandinsky. Murnau – Johannisstrasse from a Window of the Griesbräu, 1908. Lenbachhaus Munich, Donation of Gabriele Münter, 1957.

Of course, the name “Blue Rider” is synonymous with the two artist-editors behind the almanac – Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944, Russian) and Franz Marc (1880-1916, German) – yet Tate has chosen instead to name-check Kandinsky and his partner Gabriele Münter (1877-1962, German) in the exhibition title. One might cynically wonder whether this is but an attempt to tick some of those equality and diversity boxes, but, in fact, Münter played a pivotal role in the group – not only as a fantastic artist in her own right, but as the owner of the “Yellow House” in Murnau (a small market town on the Staffelsee, south of Munich in the Bavarian Alps), which became the hub of much Blue Rider activity, and as the benefactor who gave a large collection of works by Kandinsky, herself, and their friends to the Lenbachhaus in Munich in 1957, establishing a lasting legacy for the group. Appropriately, Münter is well represented in this exhibition – I would take a punt and say more so than any other artist – with examples included of her paintings, woodcuts, photography and reverse glass paintings.

The Blue Rider artists were interested in all these different mediums, as well as performance, theatre and music; folk, children’s and “primitive” art; printmaking and artist books. It is astounding to think that the Blue Rider Almanac2 was compiled and produced in under a year and the two exhibitions were planned, curated, organised and installed in only two to seven weeks, ahead of the almanac’s launch. After these three central undertakings, however, the group had only a few projects, many of which remained unrealised, before the outbreak of the first world war led to its dissolution. Among the unrealised projects were a second volume of the almanac and a publication of Bible illustrations by Marc, who said matter-of-factly of the group: “In Munich the first and only serious representatives of the new ideas were two Russians who had lived there for many years and who had worked quietly until some Germans joined them.”3

Franz Marc. Cows, Red, Green, Yellow, 1911. Lenbachhaus Munich.

Regarding the name, the Blue Rider, Kandinsky explained in an article in 1930: “We invented the name ‘Der Blaue Reiter’; we both loved blue, Marc liked horses, I riders. So the name came by itself.”4 In fact, Marc liked many animals, and the exhibition also includes the energetic Cows, Red, Green, Yellow (1911), Tiger (1912) and Deer in the Woods II (1912), among others, as well as numerous examples of his woodcuts, alive with a whole menagerie. Although animals are not the primary subject of any of the other artists, there is also an endearing woodcut by Münter – Habsburg Square (1912-13) – which depicts a street scene, with mother and child, horse and cart, and a couple of (rather fox-like) dogs, and The Cow (1910) by Kandinsky, which I confess to never having recognised as a cow before (but now that I know, it is, of course, quite obvious).

Franz Marc. Tiger, 1912. Lenbachhaus Munich, Donation of the Bernhard and Elly Koehler Foundation 1965.

It was Münter who put it the best, when she said of the Blue Rider: “We were only a group of friends who shared a common passion for painting as a form of self-expression. Each of us was interested in the work of the other … in the health and happiness of the others … I don’t think we were ever as programmatic in our theories, as competitive or as self-assertive, as some of the modern art schools.”5 The age range of the group spanned 27 years and comprised artists at very different stages of their careers, but all were brought together in the cauldron that was Munich – and, a little later, Murnau, of which Münter and Kandinsky painted many scenes, such as the latter’s Murnau with Church I (1910), saturated colour on card, the white church tower with its traditional Bavarian onion dome a clearly recognisable motif.

Gabriele Münter. Murnau Farmer’s Wife with Children, 1909–1910. Lenbachhaus Munich, Donation of Gabriele Münter, 1957 © DACS 2024.

The tale of the early days – and of the NKVM – in Munich is spun largely around the figure of its protagonist, Marianne Werefkin (1860-1938, Russian), who hosted gatherings – known as the “Pink Salon” – in her home in Giselastraße, to which she had moved in 1896 with Alexej Jawlensky (1864-1941, Russian). The salon’s attendees – not just visual artists, but also dancers, poets and philosophers – were dubbed “Giselists”, and Werefkin – a wealthy heiress, collector and artist – was often referred to as “Baronin” (Baroness). Museum director Gustav Pauli wrote of her: “The centre, so to speak the main transmitter of the waves of energy so great you could almost feel them, was the Baroness,”6 and the artist Wladimir Bechtejeff embellished: “Marianna Vladimirovna (Werefkina) was an extraordinary woman who had her own inner world, far removed from everyday life and social conventions, as was apparent in the life she led together with Jawlensky … The highly intellectual and artistic atmosphere of this house, generated by Werefkin’s outstanding intelligence and Jawlensky’s brilliant gifts, attracted talented people.”7 I want to dwell a little on this woman, as the exhibition really brings her out of the shadows, and I was excited to see so many of her paintings, and glad to be able to learn about her in the catalogue essays.

Werefkin started painting at the age of 14 after falling ill, and it is said that her first pictures depicted visions owing to her high temperature.8 In 1888, her career suffered a considerable setback when she shot herself in her right hand in a hunting accident and had to learn to paint with her non-dominant left hand. The silver lining to this was that she had to travel to Germany for medical treatment, where she had the opportunity to encounter western-European art in the museums of Berlin, Dresden and Munich. Werefkin’s father was a commander-general in the Russian army, and, when he died in 1896, Werefkin, by now in her mid-thirties, was allowed to keep his government pension – on the condition she remain single. That same year, she moved with Jawlensky to Munich, where they lived in adjoining apartments. Jawlensky attended a private art school, while Werefkin studied art history. She necessarily declined his marriage proposal, but they remained friends. She wrote in her journal (which she kept in French): “For four years already we sleep together. I remained a virgin, he became a virgin again. Between us sleeps our child – art. It is the child who ensures our undisturbed sleep. Carnal desire has never once befouled our bed. We both want to remain unsullied, so that not a single impure thought could ever disturb the calm of our nights when we are so close to each other. And yet we love each other. Since we exchanged declarations of love many years ago we have not kissed once even for form’s sake. He is everything for me, I love him as a mother, especially as a mother, as a friend, a sister, a wife, I love him as an artist and a friend. I am not his mistress and my tenderness has never had a passionate turn.”9

Werefkin was so devoted to Jawlensky that she put her own artistic career on hold for almost a decade in order to advocate for and advance his work. She also collected work by her wider circle of friends, and developed forward-thinking ideas on art and its theories.10 As a result of this, as well as her fostering artistic conversations at her salon, a contemporary critic dubbed Werefkin “a midwife of abstraction,” and the expressionist poet, Else Lasker-Schule, gave her the honorary title “Amazon of the Blue Rider”.11 When, in 1906, Werefkin once again took a up her paintbrush, she was a completely changed artist. Henceforth, she painted only in egg tempera, and her style reflected the innovations of symbolism, fauvism and cloisonnism. Despite her epithets, she and Jawlensky – unlike Kandinsky – never moved into abstraction.

Her painting, The Skaters (1911), in which a mass of dark figures glides in anticlockwise circles across a moonlit rink, is juxtaposed, in this exhibition, with two theatrical pictures – Summer Stage (1910) and Marionette Theatre with Jawlensky and Marianne Werefkin in the Foreground (1917-18). In many ways, the ice rink is equivalent to a stage, with the moon and brightly lit building making a dramatic backdrop. Also, the simply amazing and so acutely expressive clenched hands of the women wailing as they watch their men drowning in The Storm (1907) makes Werefkin, for me, without a doubt, the surprise star of the show.

Marianne von Werefkin. Self-portrait I, c1910. Lenbachhaus Munich.

Werefkin’s striking Self-Portrait (c1910) – painted at the age of 50 for inclusion in the following year’s NKVM exhibition – uses broad, loose brushwork, showing the influence of artists such as Vincent van Gogh, whom she openly admired, and vibrant primary colours, with glinting red eyes, making a nod to both Paul Gauguin and Edvard Munch.12 “At a time when to be an independently minded woman was regarded as eccentric,” art historian Charlotte de Mille writes in her catalogue essay, “Werefkin self-consciously constructed personal and artistic identities that were performative, as well as provocative.” She goes on to note that Werefkin “struggled to reconcile her creativity with the late-19th-century trope of male creative genius,” and proposes that she “consciously harnessed the concept of the ‘third sex’ proposed by sexologist Magnus Hirschfeld in 1904, and a Mannweib or ‘manwoman’, a term commonly used to describe (pejoratively) women artists”.13 In her journal, Werefkin wrote: “I am not man, I am not woman, I am myself.”14 De Mille suggests that Werefkin’s self-portrait captures the “male gaze that calls for a slap,”15 with “dazzling red eyes, daring us to contradict her professional choice”.16 This self-portrait is complemented, in the exhibition, by portraits of Werefkin by Erma Bossi (1975-1952, Austro-Hungarian – from the modern-day Croatia) – which makes her seem an elegant lady, indeed a baroness – and Münter (Portrait of Marianne Werefkin, 1909) – which, painted in front of the yellow wall of Münter’s house, is far more suggestive of Werefkin’s personality, and of which Münter said: “She was a woman of grand appearance, self-confident, commanding, extravagantly dressed, with a hat as big as a wagon wheel.”17

Gabriele Münter. Portrait of Marianne von Werefkin, 1909. Lenbachhaus Munich, Donation of Gabriele Münter, 1957 © DACS 2024.

With her interest in theatre and her concepts of gender, it is not really surprising that Werefkin should have been drawn to the gender-fluid dancer Alexander Sacharoff (1886-1963, Russian – from the modern-day Ukraine) as a model. The Dancer Alexander Sacharoff (1909), for example, depicts him wearing a blue dress, with a blue bob, standing against a blue background, with a flower in his hand which looks more like a butterfly – perhaps symbolic of transformation? It is a simply fantastic painting, but, at the same time, terrifyingly ugly – with Sacharoff looking like the evil queen of a pantomime. A nearby vitrine contains small sketches – as well as photos – of the performer. I confess, I hadn’t realised quite how many of Werefkin’s – and Jawlensky’s – pictures depict Sacharoff (and in many cases I thought the muse must have been female). Another good example is Jawlensky’s Spanish Woman (1913), with his trademark elliptical eyes and masses of dark hair, suggestive of curls, through the clearly delineated individual brush strokes.

Marianne von Werefkin. The Dancer, Alexander Sacharoff, 1909. Fondazione Marianne Werefkin, Museo Comunale d'Arte Moderna, Ascona.

Münter’s and Kandinsky’s relationship was no less complex than that of Werefkin and Jawlensky. They got to know one another when Münter enrolled in one of his classes at Phalanx, an alternative art school in Munich. When they met, Kandinsky had already been married for 10 years to his cousin, Anna. Münter soon insisted he make a choice, but Kandinsky was in no hurry to commit, and proceeded to go back and forth between his two women. Münter and he spent some time travelling around Europe and northern Africa, but they were often refused a double room in hotels because of their illicit status. In 1909, Münter bought her house in Murnau, hoping to make it a family home. This, however, was never to be. Their relationship was on-off, complicated by moves abroad and the war. Ultimately, Kandinsky fell in love with another Russian, 27 years his junior, whom he married. Münter lived the rest of her life in the yellow house in Murnau. The inclusion of a number of her black-and-white travel photographs in the exhibition is a step away from the work of the Blue Rider and, as far as I am concerned, adds nothing. An early painting by Kandinsky, showing Münter, from behind, in a blue smock, working at her easel en plein air (Kallmünz – Gabriele Münter Painting II, 1903) is testament to the artistic core of their relationship.

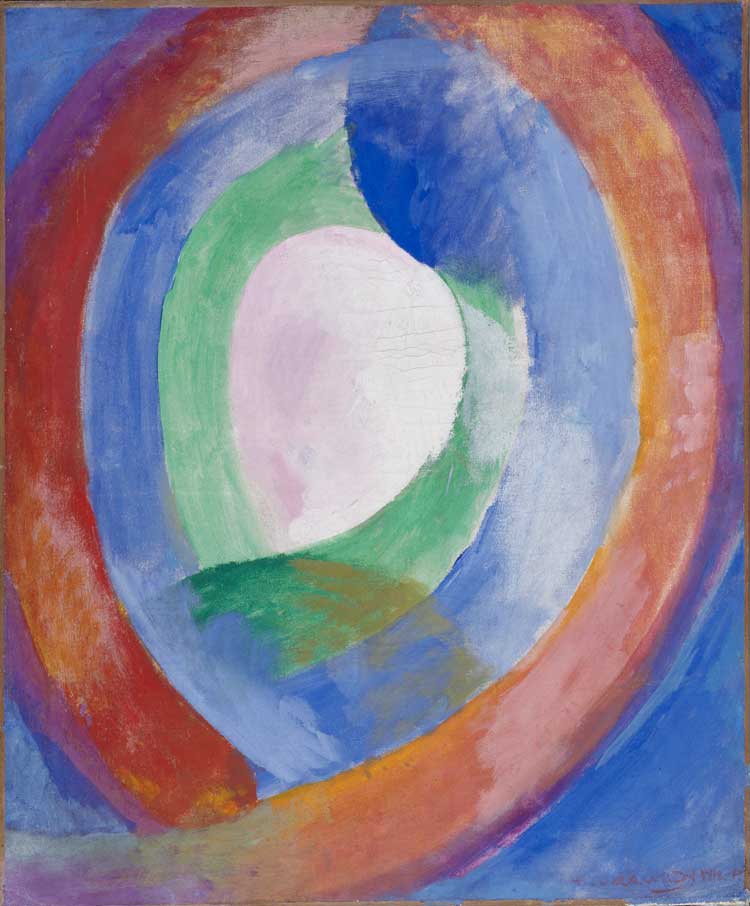

Robert Delaunay. Circular Shapes, Moon no. 1, 1913. Lenbachhaus Munich and Gabriele Münter and Johannes Eichner Foundation, Munich.

A key premise of the exhibition is to consider the “transcultural” influences in and on the Blue Rider group, with the following quote from the preface to the almanac being used by Tate as its plug: “In our case the principle of internationalism is the only one possible … The whole work, called art, knows no borders or nations, only humanity.”18 A case in point is the Delaunays – Robert (1885-1941, French) and his wife Sonia (1885-1979, Russian – from the modern-day Ukraine). Robert, who worked with colour theory, contributed an article to the almanac, and Kandinsky and Marc were both enthusiastic about his work and what he might bring to the group.19 Lyonel Feininger (1871-1956, USA) and Paul Klee (1879-1940, Swiss) were also both associated with the group. Nevertheless, as Sidlina notes: “We remain conscious of the fact that these artists [by whom she means Kandinsky and Marc] were involved in – indeed, largely instrumental in setting up – the structures of a canon of modern art that, as Dorothy Price has put it, ‘was to remain mute for many decades about the inherent violence on which its very modernism was premised’.”20 A thought-provoking and challenging discussion of colonialism and racism is laid out in Bibiana K Obler’s chapter in the catalogue, which opens with a quote from Kandinsky from 1913: “At first, the canvas stands there like a pure, chaste maiden, with clear glaze and heavenly joy – this pure canvas that is itself as beautiful as a picture. And then comes the imperious brush, conquering it gradually, first here, then there, employing all its native energy, like a European colonist who with axe, spade, hammer, saw penetrates the virgin jungle where no human foot has trod, bending it to conform to his will.”21 While seeking to “confront this ugly aspect of history,” Obler continues to note: “Unlike the Brücke group, which was more nationalist in outlook, with primitivist inspirations derived largely from German colonies, the expressionist groups in southern Germany … were inherently more international given that multiple nationalities were represented among the members. The emphasis on humanity was not only about national borders but also gender and class: informed by anarchist sympathies, the groups included women and men, and were concerned with vernacular and applied arts alongside fine arts.”22 Nevertheless, despite representation in the almanac being “exceptional in its range,” it contained only three credited artworks by women (out of a total of 141 illustrations), and, while the European avant-garde (and European white male self-taught artist Henri Rousseau) received acknowledgment by name, all the other artists included remained anonymous – even when their names would have been readily available. Additionally, while almost all of the European art (both high and low) was reproduced in full, much of the non-European art was cropped, emphasising, as Obler puts it, “difference”.

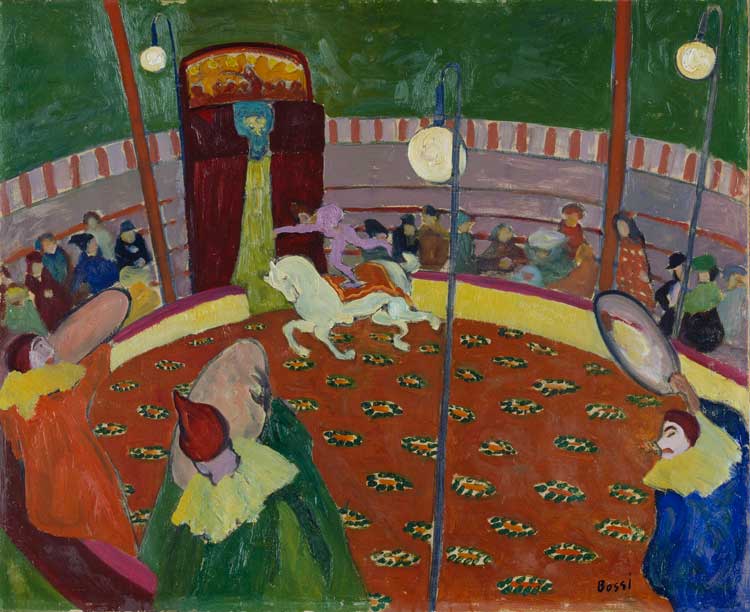

Erma Bossi. Circus, 1909. Lenbachhaus Munich, on permanent loan from the Gabriele Münter and Johannes Eichner Foundation, Munich.

The role of women in the Blue Rider, was, however, as we have already seen in the characters of Münter and Werefkin, absolutely critical. The exhibition goes further, showcasing works by several other female artists associated with the group, including, as already mentioned, Bossi and Delaunay, and then Elisabeth Epstein (1879-1956, Russian – from the modern-day Ukraine) and Maria Franck-Marc (1876-1955, German). Franck-Marc, Marc’s wife, is one of my “new discoveries” (thanks to the exhibition), and Three Wise Men (c1911) is stunning in all its golden yellows and exoticism (an elephant and a camel appear in the background). The bright rays of the Star of Bethlehem pierce the composition and are echoed in the shape of the protagonists’ skirts. But the best detail is the sheet music, which almost forms a part of the left-most man’s head-dress. This picture is every bit as musical as Kandinsky’s abstract Impressions (Impression III (Concert), 1911, for example, was made from his memory of a performance of works by his friend Arnold Schönberg (1874-1951, Austro-Hungarian), and is shown here in a room dedicated to sound, in which Schönberg’s music is playing on a loop.). Moreover, as the following quote from a letter from Marc to August Macke (1887-1914, German) suggests, Kandinsky may well have come upon the concept of synaesthesia, which was to become increasingly important in his work, thanks to Franck-Marc: “I recently had a conversation with Kandinsky about Schönberg, and laid before him the conclusion ... that Maria has drawn from his music (she maintains that he works with completely unresolvable sound-mixtures, without any tonal colour, only expression, gesture). Kandinsky was very inspired by it: that is his aim.”23

Maria Franck-Marc. Girl with Toddler, c1913. Lenbachhaus Munich. © Legal succession of the artist.

Franck-Marc’s Girl with Toddler (c1913) and Two Children between Flowers (1912) are also noteworthy since they reflect the influence of Paula Modersohn-Becker, who painted her figures in a similarly “child-like” or “primitive” style, and whom Franck-Marc met while under the tutelage of her husband, Otto Modersohn, in the summer of 1905, in the artist colony in Worpswede, near Bremen, in northern Germany.

,-1909.jpg)

Gabriele Münter. Listening (Portrait of Jawlensky), 1909. Lenbachhaus Munich, Donation of Gabriele Münter, 1957 © DACS 2024.

Returning to Münter, what I particularly love about her paintings are their familiarity and the recognisable objects and motifs that recur like little friends. For example, Madonna with Poinsettia (c1911) is here shown alongside the very wooden statuette of Mary that it depicts. The characters in her compositions are also often her friends – that is, the artists of the Blue Rider – shown sitting around the kitchen table, frequently deep in conversation. Her portraits, although sketchy, offer glimpses into their characters and personalities, as well as the power dynamics between them. In particular, she said of Listening (Portrait of Jawlensky) (1909) that it shows the Russian “with an expression of puzzled astonishment on his chubby face, listening to Kandinsky’s new theories of art”.24 There is also Kandinsky and Erma Bossi at the Table (1912) and Man at the Table (Kandinsky) (1911), where his hand is but a peach ellipse, and his legs are submerged in a sweeping dark shadow coming into the composition from the left-hand side.

Gabriele Münter. Kandinsky and Erma Bossi at the Table, 1912. Lenbachhaus Munich, Donation Gabriele Münter © DACS 2024.

As already noted, while Kandinsky was to turn to abstraction, Werefkin remained firmly in the figurative camp. Matthias Mühling, director of the Lenbachhaus, writes in his essay in the catalogue: “The Blue Rider decidedly eschewed any common aesthetic. Contrary to what is often assumed, the development of non-figurative form wasn’t its central goal …

What the endeavours of the Blue Rider do have in common, however, is that the supposed heterogeneity of the participants and their artistic production is lent a recognisable cohesion by the intellectual superstructure of the ‘spiritual’, based on a diversity of expressive means. The truly astonishing aspect of ideas in the circle of the Blue Rider is the fact that the ‘question of form’ is not at the centre of their considerations: instead, the central question is what the ‘form’ stands for, what it is capable of conveying. In his almanac text ‘On the Question of Form’, Kandinsky clarified: ‘One should not battle over form for any longer than it can serve as the means of expression of the inner sound ... One must regard as correct (= artistic) every form that is the external expression of inner content.’”25 Once again along similar lines, Werefkin wrote succinctly: “All true art is constituted of the impression received and the expression that derives therefrom.”26

Auguste Macke. Promenade, 1913. Lenbachhaus Munich, Donation of Bernhard and Elly Koehler 1965.

Towards the end of the exhibition, there are three “experiential” – AKA sensory – rooms in which the visitor is invited to explore “the Blue Rider’s engagement with sound, colour and light”.27 Again, this feels like something of a box-ticking exercise, especially with the reference to synaesthesia as a “neurodiverse condition” (which, to be fair, it is, but I had never seen it explicitly labelled as such before). What perhaps wasn’t taken into consideration was that, by positioning these spaces last in a sequence of many sensorily stimulating rooms, it is more than likely that the average neurodiverse (come to that, also the average neurotypical) visitor will already have reached sensory overload by this point – this was certainly so in my case. The “sound” room is the aforementioned one with the Kandinsky and Schönberg. Then there is a “colour” room, with a display explaining various different colour theories by proponents including Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, who, a century earlier, had written about the psychological impact of different colours on mood and emotion, and Isaac Newton, who developed the prismatic arrangement of colour theory at the end of the 17th century. This latter was explored by Marc, who experimented with viewing his works-in-progress through a prism, so as to employ the purest colours which, in modern-day parlance, might be described to “pop”. An achromatic doublet prism has been installed in the gallery for visitors to look through, reminiscent of those telescopes situated along coastal cliffs, offering a view to those with a 20-pence coin to spare (although possibly the rate has gone up since I was a child!). I confess I was too tired to make the effort to engage by this point. Finally, there is a “light” room, with an installation – Lichtdecke Kandinsky (temporary light installation) (2006) – by the contemporary Danish artist Olafur Eliasson (b1967, Copenhagen), in which the lighting in the room, with Kandinsky works on its walls, changes ever so slowly and subtly. Sadly, this also seemed relatively pointless, since I was amid a group of art critics that stood around for a good 30 minutes and could perceive no change or effect.

Overall, however, I loved this exhibition – as I knew I would – for the happiness from seeing “old friends” and the exuberant joy of colour and form. It is a rare treat to see so many works brought to London from the Lenbachhaus, with whom this is a collaboration. And “collaboration” is really the key takeaway, when we think about the friendships, relationships and mutual support exemplified by the artists on display. The sub-themes of each room could easily be expanded into exhibitions in their own right, so let’s hope it’s not another 64 years before the next UK outing of the Blue Rider. I might be popping back for another stroll around this one though – just in case.

References

1. For Example, The Blue Rider by Natalia Sidlina, in Expressionists: Kandinsky, Münter and the Blue Rider, exhibition catalogue, Tate Modern, London, 2024, page 14.

2. The almanac was published in May 1912. An English translation appeared in 1974 and is available in reprint as The Blaue Reiter Almanac, edited by Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc, translated by Henning Falkenstein, Tate Publishing, London, 2006.

3. Franz Marc cited in A History of the Almanac by Klaus Lankheit, in The Blaue Reiter Almanac, edited by Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc, translated by Henning Falkenstein, Tate Publishing, London, 2006, page 12.

4. Der Blaue Reiter (Rückblick) by Wassily Kandinsky in Das Kunstblatt XIV, 1930, cited in A History of the Almanac by Klaus Lankheit, in The Blaue Reiter Almanac, edited by Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc, translated by Henning Falkenstein, Tate Publishing, London, 2006, page 18.

5. Gabriele Münter in Dialogues on Art by Edouard Roditi, New York, 1960, pages 142-43, cited in For Example, The Blue Rider by Natalia Sidlina, in Expressionists: Kandinsky, Münter and the Blue Rider, exhibition catalogue, Tate Publishing, London, 2024, page 12.

6. Werefkin and her Salon by Niccola Shearman, in Expressionists: Kandinsky, Münter and the Blue Rider, exhibition catalogue, Tate Publishing, London, 2024, page p176.

7. The Possibilities of Place by Dorothy Price, in Expressionists: Kandinsky, Münter and the Blue Rider, exhibition catalogue, Tate Publishing, London, 2024, page 27.

8. Marianne Werefkin: The Woman and the Artist by Natalya Tolstaya in Tretyakov Gallery Magazine #3 2010 (28) www.tretyakovgallerymagazine.com/articles/3-2010-28/marianne-werefkin-woman-and-artist.

9. Lettres à un inconnu: Aux sources de l'expressionnisme by Marianne Werefkin, edited by Gabrielle Dufour-Kowalska, Klincksieck, Paris, 1999, pages 75-77.

10. When Kandinsky published his influential book Concerning the Spiritual on Art (1911-12), Werefkin claimed it contained a number of her ideas.

11. Marianne Werefkin (Tula 1860 – Ascona 1938). L’amazzone dell’avanguardia, exhibition catalogue, Alias, Rome, 2010, page 113, cited in Marianne Werefkin: The Woman and the Artist by Natalya Tolstaya in Tretyakov Gallery Magazine #3 2010 (28) www.tretyakovgallerymagazine.com/articles/3-2010-28/marianne-werefkin-woman-and-artist.

12. Entry for Marianne von Werefkin on The Art Story, www.theartstory.org/artist/von-werefkin-marianne.

13. Marianne Werefkin – ‘Noble Wild Lad’ by Charlotte de Mille, in Expressionists: Kandinsky, Münter and the Blue Rider, exhibition catalogue, Tate Publishing, London, 2024, page 92.

14. Transcending Gender: Cross-Dressing as a Performative Practice of Women Artists of the Avant-Garde by Marina Dimitrieva, in Marianne Werefkin and the Women Artists in her Circle, edited by Tanja Malycheva and Isabel Wünsche, Brill | Rodopi, Leiden, 2016, page 71.

15. Werefkin’s words, cited in Veiling Venus: Gender and abstraction in early German modernism by Shulamith Behr, in Manifestations of Venus: Art and Sexuality, edited by Caroline Arscott and Katie Scott, Manchester University Press, Manchester, 2000, page 136.

16. Marianne Werefkin – ‘Noble Wild Lad’ by Charlotte de Mille, in Expressionists: Kandinsky, Münter and the Blue Rider, exhibition catalogue, Tate Publishing, London, 2024, page 92.

17. Cited in the gallery text to accompany the exhibition.

18. Draft preface to The Blue Rider Almanac, 1911, cited in Expressionists: Kandinsky, Münter and the Blue Rider, Tate Dialogues, Tate Publishing, London, 2024, page 1.

19. The French Connection by Kimberly A Smith, in Expressionists: Kandinsky, Münter and the Blue Rider, exhibition catalogue, Tate Publishing, London, 2024, page 86.

20. For Example, The Blue Rider by Natalia Sidlina, in Expressionists: Kandinsky, Münter and the Blue Rider, exhibition catalogue, Tate Publishing, London, 2024, page 19.

21. Reminiscences by Wassily Kandinsky, 1913, in Kandinsky: Complete Writings on Art, edited by Kenneth Lindsay and Peter Vergo, Da Capo Press, London, 1982, vol 1, pages 372-73, cited in The Imperious Brush: Interrogating Expressionist Relations by Bibiana K Obler, in Expressionists: Kandinsky, Münter and the Blue Rider, exhibition catalogue, Tate Publishing, London, 2024, page 79.

22. The Imperious Brush: Interrogating Expressionist Relations by Bibiana K Obler, in Expressionists: Kandinsky, Münter and the Blue Rider, exhibition catalogue, Tate Publishing, London, 2024, page 79.

23. Franz Marc, letter to August Macke, 14 February 1911, in Arnold Schoenberg, Wassily Kandinsky: Letters, Pictures and Documents, edited by Jelena Hahl-Koch, translated by JC Crawford, Faber & Faber, London, 1984, page 137, cited in Dissonances in Art: Music and the Blue Rider by Charlotte de Mille, in Expressionists: Kandinsky, Münter and the Blue Rider, exhibition catalogue, Tate Publishing, London, 2024, page 140.

24. Cited in the gallery text to accompany the exhibition.

25. ‘In Defiance of their Times’: The Blue Rider Project by Matthias Mühling, in Expressionists: Kandinsky, Münter and the Blue Rider, exhibition catalogue, Tate Publishing, London, 2024, page 126.

26. Lettres à un inconnu by Marianne Werefkin, cited in Werefkin and her Salon by Niccola Shearman, in Expressionists: Kandinsky, Münter and the Blue Rider, exhibition catalogue, Tate Publishing, London, 2024, page 176.

27. Cited in the gallery text to accompany the exhibition.