Museum Ludwig, Cologne

15 September 2018 – 13 January 2019

by ANNA McNAY

The German painter Gabriele Münter (1877-1962) holds a special place in my heart, since, at the age of 17, I spent the summer in the small and charming Bavarian Alpine town of Murnau, completing a language course at the Goethe Institute, and there encountered for the first time the work of Münter and her contemporaries. For it was in Murnau that the Berlin-born artist settled in 1909; there that she and Russian émigré artist Wassily Kandinsky lived together in the “Yellow House”, which went on to become the birthplace of the Blaue Reiter (Blue Rider group of expressionist artists); and there that she continued to live until her death, at the age of 85. The Staffelsee (the lake on the shores of which Murnau sits), the onion-shaped dome atop the church tower, and the purple and green Alps in the distance are all sights that warm my heart, much as they must have done Münter’s, given the number of times that she painted them. As soon as I read the announcement about Gabriele Münter: Painting to the Point, at the Museum Ludwig, this exhibition was therefore a must for me.

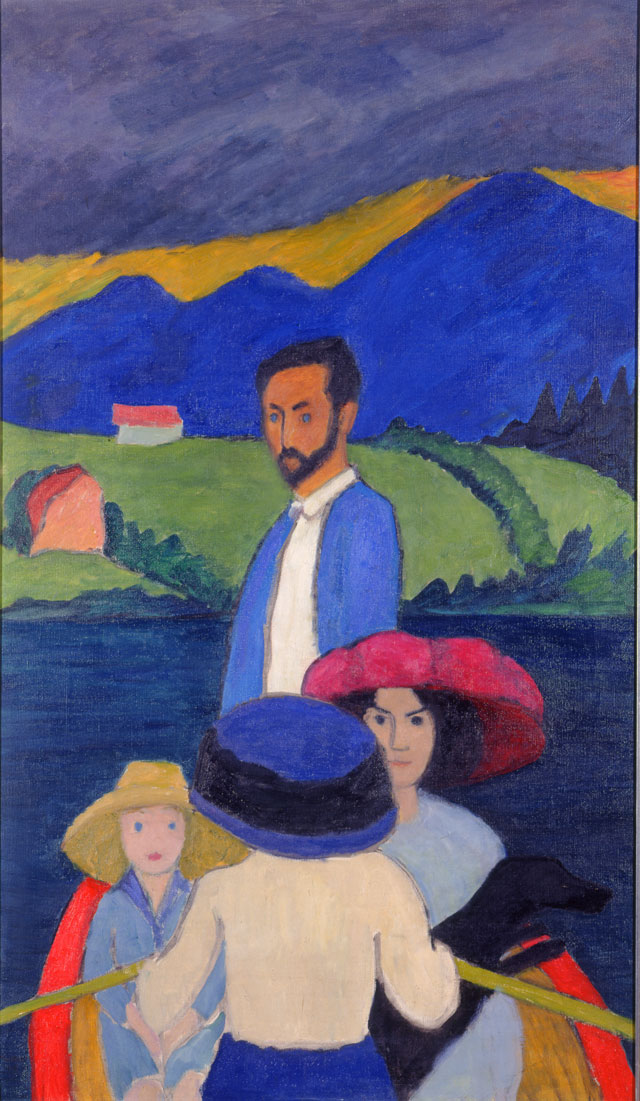

Gabriele Münter. Boating, 1910. Courtesy of the Milwaukee Art Museum, Gift of Mrs. Harry Lynde Bradley. © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2018. Photo: Efraim Lev-er, © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris.

Münter, born at a time when women were still not permitted to attend art school, was able to study at a private academy, thanks to an inheritance from her father. In 1901, she travelled south to Munich where she first met Kandinsky, who was to be her tutor. The pair soon formed a marriage of the mind, although Kandinsky, 11 years Münter’s senior, was already married to his cousin, Anna Chemyakina. Regardless, the couple became officially engaged a year later, and started a period of travel, incorporating Holland, Tunis, Italy and Paris, during which time Münter experimented with and developed various styles and techniques. The nice thing about this exhibition – put together in collaboration with the Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus und Kunstbau München, the Gabriele Münter and Johannes Eichner Foundation in Munich and the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Humblebæk, Denmark – is that the curators were keen to show visitors both what they come expecting to see – namely the landscapes of Murnau and some of Münter’s better-known portraits – but also to demonstrate just how wide and varied her oeuvre really was. Thus, a couple of rooms at the outset are filled with works from these earlier years, in particular a section of impressionist-style works from 1907, when Münter spent the year in Paris and Sèvres.

Gabriele Münter. Breakfast of the Birds, 1934. Courtesy of the National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington D.C. Gift of Wallace and Wilhelmina Holladay. © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2018. Photo: Lee Stalsworth.

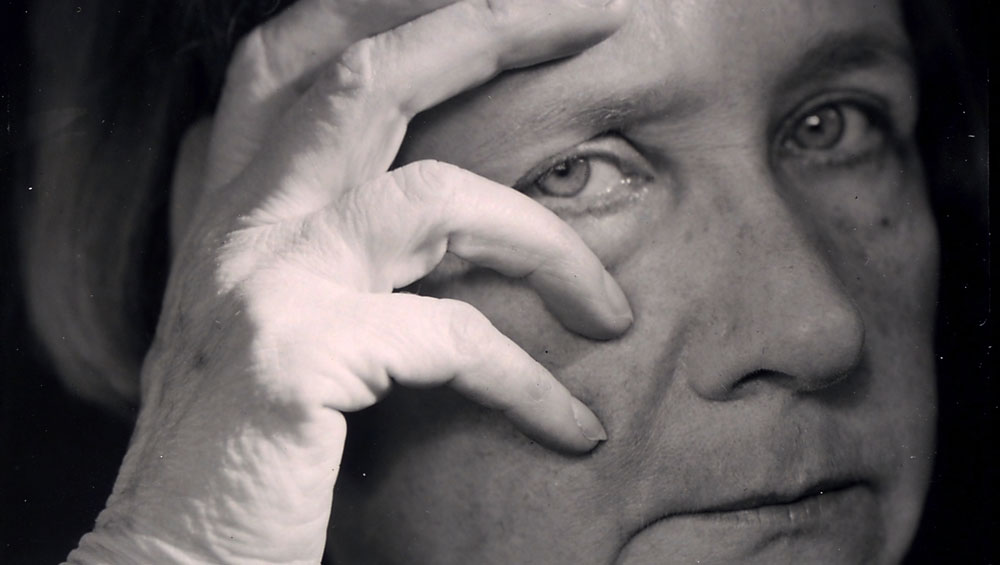

The exhibition is hung thematically rather than chronologically, as Münter’s stylistic trajectory was not one of linear development, but very much a story of experimentation and repeated returns to particular motifs and subjects. For example, one common motif in her work is the inclusion of herself in the composition, seen from behind, as for example in Boating (1910) and the later Breakfast of the Birds (1934), where she sits at her table, laid with coffee, milk and bread, looking out on to snow-capped trees, where blue tits peck for titbits.

The suggestion put forward by the curators is that the concept for this might have been born in her early photographs, taken with a Kodak No 2 Bull’s-Eye camera, when, aged 21, shortly before moving to Munich, she took a two-year journey to the US with her sister Emmy. Little Girl Standing at the Side of a Street, Saint Louis, Missouri (1900) – one picture from a roomful on display (she took more than 400 throughout the trip) – captures Münter’s shadow falling across the pavement in the foreground.

Gabriele Münter. Little Girl Standing at the Side of a Street Saint Louis, Missouri, 1900. © Gabriele Münter und Johannes Eichner-Stiftung VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2018.

This holiday is considered to be where Münter’s art really took its roots, with a further photograph of Aunt Annie’s House (1899), sited alone in an otherwise empty landscape, bearing a striking similarity to many of her later compositions.

During her early years in Murnau, and her time together with Kandinsky, Münter was close friends with fellow Blue Rider artists Alexej von Jawlensky (described as a “listener”, in contrast to Kandinsky, who was always the one to hold forth on such subjects as the spiritual in art) and his partner Marianne von Werefkin, whom she described as “pompös” (albeit seemingly without any intended negative connotations). Of the 250 portraits painted by Münter throughout her career, about four-fifths were of women. Her portrait of Werefkin (from 1909) has been described as “the star of the show”, so striking and well known is it today. The bright yellow background, graphic outlining of the figure and greenish tint to her face are all recurring features in the work not only of Münter, but also her artist friends.

Gabriele Münter. Portrait of Marianne Werefkin, 1909. Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus und Kunstbau München© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2018. Photo: Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus und Kunstbau München.

After the outbreak of the first world war, Kandinsky, now an unwelcome alien, returned to Moscow, from where he wrote to tell Münter he was living alone and preferred it that way. She sought in vain to reignite their relationship, and, in 1915, they met for one final time in the neutral Stockholm. Later, Münter discovered he had married someone else. With the loss of Kandinsky, she also lost her tutor and her artistic circle. Nevertheless, she returned to Murnau in 1920. Shortly thereafter, Kandinsky requested the return of his things, including nearly all of his prewar work. Münter sued, demanding compensation for the shame brought on her. When the case was settled in 1926, much was returned to Kandinsky, but Münter retained almost 1,000 of his works. Despite entering into a relationship with the art historian Johannes Eichner in 1929, Kandinsky remained the love of Münter’s life. She said: “He loved, understood, protected and promoted my talent.”1

Gabriele Münter. In the Garden in Murnau, 1911. Neue Galerie New York. This work is part of the collection of Estée Lauder and was made available through the generosity of Estée Lauder. © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2018. Photo: Hulya Kolabas.

During the 1930s, Murnau was a heavily National Socialist dominion, with half its population voting for Hitler. Münter’s unsettling painting Procession in Murnau (1934) depicts the feast of Corpus Christi, with Nazi flags hanging from all the windows. Eichner advised her to paint less expressionistically so as not to attract trouble for herself. Two paintings from her series of a blue digger – still fairly expressionist in style, but depicting the Nazi-friendly theme of the construction of the Olympiastraße through the countryside to Garmisch-Partenkirchen for the 1936 Winter Olympics – were included in Hitler’s 1937 salon, the Große Deutsche Kunstausstellung. Münter further managed to evade being defamed as a degenerate artist, perhaps largely due to the fact that the Nazis primarily went around selecting artists from national collections and, by and large, Münter was not included in these. In fact, despite its excellent collection of German expressionism – the Sammlung Haubrich – the Museum Ludwig, until now, has not owned any work by Münter. The Wallraf-Richartz Museum, also in Cologne, owns a small painting – included in the exhibition here – but it is from Münter’s early Parisian years, and therefore very impressionistic in manner.

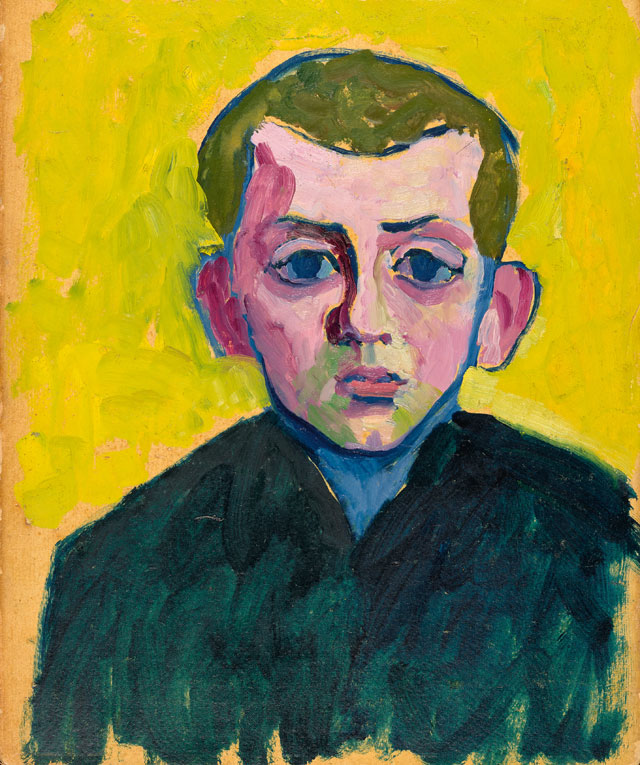

In 1925, Josef Haubrich organised a major solo exhibition of works by Münter at the Kölnischer Kunstverein (where he was chairman), which toured several other venues, but he still didn’t acquire anything for his collection. Part of the reason for the Museum Ludwig wanting to host this touring exhibition was, therefore, to raise awareness and funds to help acquire Head of a Young Boy (Willi Blab) (1908) – a campaign which has happily proved successful, meaning that this work, on prominent display outside the main entrance to the exhibition, will now remain in Cologne.

Gabriele Münter. Head of a Young Boy (Willi Blab), 1908. Gabriele Münter und Johannes Eichner-Stiftung, Munich © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2018. Photo: Simone Gänsheimer, Ernst Jank, Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus und Kunstbau München.

One of Münter’s early Murnau works, it is exemplary of her shift in style from her earlier impressionism to the more graphic, bold and colourful expressionism (the boy is outlined in blue against a vivid yellow background), as well as being left casually “unfinished”, with bare threads at the bottom of the canvas.

Gabriele Münter. Abstract, 1914. Gabriele Münter und Johannes Eichner-Stiftung, Munich. © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2018. Photo: Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus und Kunstbau München.

Throughout her career, Münter showed periods of experimentation with abstraction, including the pair of works shown here in juxtaposition – At the Café and Abstract Interior (both 1914) – where the latter might better be described as “abstracted” than “abstract”, and, from later in her life, in her 70s, Abstract (Middle Light Blue, Oval) (1954) and With Two White Arrows (1952), produced in a period when, along with many other artists, she sought to consider the question of how art might seek to redefine itself postwar. Nevertheless, Münter remained a figurative painter through and through, never allowing herself to be led by others, not even Kandinsky. Often, however, unrecognisable shapes or objects can be seen to dominate the centre of a composition – for example, in Woman in Thought (1917), where the red shape which, on closer observation, can be traced back to being a flower, at first glance bears more similarity to the red lamp alongside which it hangs. This epitomises Münter’s focus on colour and shape, although expression remained the driving force behind all her work, and she spoke of “seeing” as being the key.

Gabriele Münter. Woman in Thought II, 1928. Gabriele Münter- und Johannes Eichner-Stiftung, Munich. © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2018. Photo: Lenbachhaus, Munich.

Münter also had a great interest in, and love for, children’s art and actively sought to “learn” to draw and paint like a child. Vase Rouge (1909) is one such example, about which she later declared the process still to have been too “thought out”. The exhibition also includes two actual children’s drawings, alongside Münter’s copies of them, in turn alongside a painting, Still Life with X Beer (1914), in which she has incorporated them into the composition. Münter collected children’s toys and was inspired by film and cartoon, in particular Lotte Reiniger’s Doctor Dolittle and his Animals (1928), a clip of which plays in the gallery (and a longer excerpt of which can be seen, along with excerpts from other films Münter would have seen and been inspired by, in a further viewing space at the end of the exhibition).

Gabriele Münter. Landscape with Yellow House, 1916. Private collection © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2018. Photo: Lenbachhaus, Munich.

The walls of the galleries are painted pale blue, green and yellow, to match the interior walls of the Yellow House, where Münter would have hung and considered her works during her lifetime. There are, of course, also plentiful works depicting the Yellow House itself, along with the artists and friends who frequented it. Now a museum in its own right, with works by both Münter and Kandinsky on display, both it, and the Alpine landscape, are now firmly calling my name to revisit, having been rekindled in my heart by Münter’s glorious paintings – so much better than I ever remembered, and so much more diverse. As I wandered around the galleries, I overheard two elderly ladies chattering away – one who had dragged her less-than-willing companion, who had not heard of Münter beforehand, along with her – but, by now, both were as excited and enthusiastic as each other, clamouring to know and see more. And I think this is typical of the effect that Münter’s expression-filled, colourful paintings, so full of life and joie-de-vivre, have: they are irresistible, charming and uplifting. How any self-respecting collection can be without her name, I do not know – and thankfully now, at least, the Museum Ludwig is no longer listed among these ranks.

Reference

1. “Er hat mein Talent geliebt, verstanden, geschützt und gefördert”, trans. Anna McNay. From Die Malweiber: Unerschrockene Künstlerinnen um 1900 by Katja Behling and Anke Manigold, published by Insel Verlag, 2013, page 112.